In her 1978 essay, “takin a solo/ a poetic possibility/ a poetic imperative,” Ntozake Shange interrogates literatures and criticism that submit to demands of racial representation over the possibilities of creative expression. Critiquing US literary culture’s tendency to reward writers whose voices reinforce prefabricated models of blackness, Shange observes that that, “if you are… female & black in the u.s.a./ you have one solitary voice/ though you number 3 million/ no nuance exists for you/ you have been sequestered in the monolith/ the common denominator as persona….” 1 For Shange, the imperative of racial representation constrains the range and complexity of voices and identities that can be presented in black literature, and seriously compromises literary conceptions of black women’s identity. In Shange’s work, the choreopoem form emerges as one of many ways to bridge this chasm between representation and expressive “nuance.” Developed and named by Shange in her most famous work, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (1975), the choreopoem instantiates a poetic melding of body and voice that allows Shange to probe what she calls elsewhere “the meaning of a contradiction in anybody’s body.” 2 By rendering body and voice inextricable components of creative expression, the choreopoem form allows Shange to write nuance back onto black female bodies through the communicative properties of the body, including gesture, dance, movement, and color.

Over the past three decades, Shange’s formal interventions—her signature typographies, her blending and invention of spoken languages, and her melding of lyric and movement in the choreopom form—have held particular meaning for queer and lesbian artists throughout the African diaspora. Queer Haitian-American poet and playwright Lenelle Moïse, for example, borrows the generic designation for her 2002 “choreopoem,” “Cornered in the Dark,” which explores black female sexuality and sexual violence. Likewise, queer-affirming performance group Body Ecology takes up the choreopoem genre in their mixed genre dance performances, while Keith Boykin riffs on Shange in the title of his 2012 anthology of gay men’s prose memoirs, For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Still Not Enough, following the gross lack of media attention to queer-of-color suicides in the queer suicide rash of 2010.

These artists have looked to choreopoetic thought as a means of articulating black queer experiences, identities, and lives. They take up Shange’s “poetic imperative,” musing on the choreopoem form to explore and explode contemporary conversations on race, gender, class, and ethnicity, and to mark the places in these discourses where queer sexuality lies, unspoken and untouched. These artists invite several questions about black sexuality and formal subversion: What are the queer potentials of the choreopoem form? What are its antecedents in Shange’s oeuvre, and how does it echo in the works of other writers? What does the blending of body and voice do for Afrodiasporic artists invested in speaking the many nuances of black sensory, sensual, and erotic life? What is queer about embodied voicing?

For queer women writers of the diaspora, choreopoetic thinking offers pathways for speaking oneself out of social structures that constrain the voice through willful misreadings of the body. As Kara Keeling points out, the inscription of racist, sexist, anglocentrist, and homophobic idioms onto black queer women’s bodies limits the range of subjectivites and experiences black queer women are allowed to express in dominant cultural imaginaries. 3 Class difference, differences of gender expression, and the subjective “nuance” Shange points to are erased in popular readings of black queer women’s bodies. This erasure of the expressive reaches of black queer women’s being illustrates the significance of what Hortense Spillers terms “the nuantial” for black women’s literary histories. Spillers imagines the nuantial as a nexus of black female sexual and subjective complexity written out of the black female body through what she calls “the powerful grammars of capture.” 4 The “nuantial” signals those disallowed interstices of contradiction, difference, and agential sexual desire denied black women in the violent processes of diaspora; it names that which allows us to speak about our sexuality, and that which allows us to speak at all.” 5

Together, these two models of nuance—Spillers’s disallowed “nuantial” sexual and corporeal subjectivity and Shange’s forbidden “nuance” of complex black female voicing—demonstrate the need for new grammars, new forms of seeing, speaking, and signifying black female sexuality and difference. Shange’s innovation of the choreopoem offers such a form, a poetic form and mode of expression designed explicitly to represent the complexities of intersectional identity. Through the choroeopoem, Shange develops what we might term a body/language—a strategic means of inscribing the black female body with new languages that both rewrite that body’s meanings and expand the creative and conceptual terrains on which that body can speak. Body/language allows black women artists to articulate and emphasize the many meanings of their bodies (including the many identities those bodies signify); it also enables them to create new formal modalities for inserting black female intersectionality into discourses on identity and embodiment.

For black queer writers in particular, airing the gagged far reaches of several unsanctioned subjectivities requires creative feats of both body and voice. The erasure of subjective nuance from dominant conceptions of black identity occurs largely through ideological structures and practices that disaggregate black bodies from the complex capabilities of the human voice. The overwhelming and enduring presence of stereotypes of black women in American and global narrative culture attests to dominant cultures’ structural resistance to imagining black women speaking in multiple different ways, about multiple different things, individually or collectively. 6 In the US context, caricatures such as the Mammy, the Jezebel, and the Angry Black Woman or Sapphire stereotypes instantiate what Melissa Harris Perry terms an “intentional misrecognition of black women,” which pervades American social and civic life. 7

This misrecognition of black women occurs largely through willful and repeated misreadings of black women’s bodies. The stereotyping of black female bodily expression (seen, for example, in the “eye-rolling, neck-popping” angry black woman stereotype) supports cultural and civic power imbalances in which, as Perry notes, “black women’s concerns can be ignored and their voices silenced in the name of maintaining calm and rational conversation.” 8 For black queer women, this willful misreading of the body produces multiple burdens of representation, in which the body is required to unwrite several different stereotypes—racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, classist—at once, leading to the kind of distorting visibility Keeling discusses. In this dynamic, the black queer female body must respond to so many kinds of misreading that it cannot readily speak its humanity—its impulses and its strangenesses, its fantasies, needs, and desires.

Centering nexuses of body and voice allows black queer writers to create routes of passage out of this bind of stereotyping and representation, reaffirming the kinds of pleasure, fulfillment, and healing that imperatives of monolithic representation preclude. As E. Patrick Johnson points out, “for black gay people, dancing and singing at once have transcendent spiritual potential not afforded them” in other spaces, including the black church, where external interpretations of their sexuality and erotic bodily life bar them from fully experiencing the spiritual healing available to nonqueer people. For Johnson, “the simultaneous acts of dancing and singing bridge the sacred and the secular,” allowing black queer people to create experiences of spiritual and personal fulfillment unavailable to them in spaces where their bodies and identities are stigmatized, misrecognized, or misunderstood. 9

Choreopoetic thinking creates similar opportunities for healing and transformation in literature. They serve as poetic instantiations of what Cherie Moraga terms “theory in the flesh,” in which “the physical realities of our lives—our skin color, the land or concrete we grew up on, our sexual longings—all fuse to create a politic born out of necessity.” 10 Undoing the boundaries between body and voice allows black queer women writers both to represent the processes by which their voices are unwritten, and to develop new languages that can write against the erasure of their complex subjectivities, desires, and lives.

This strategy of voicing complex black female identity through languages of the body constitutes what we might think of as a queer legacy of Shange’s choreopoetics. Since Shange’s coining of the term choreopoem in 1975, several queer women artists of the African diaspora have worked to meld body and voice in their own poetics, developing, as Shange has, new forms and genres that bring verbal and corporeal technologies together in order to reframe dialogues on identity. 11 Artists such as Moïse, Body Ecology, Achy Obejas, Zanele Muholi and others explore the interstices of body and voice to articulate the nuances of black queer women’s intersectional identities. These writers incorporate into their poetics an idea of “queerness” as an identification of sexual difference that cannot be disentangled from differences of race, gender, nation, class, and the myriad other disempowered subject positions that black queer women’s bodies can signify. They deploy queerness as a collectivizing and healing language in which, as Cathy Cohen suggests, “punks, bulldaggers and welfare queens,” emblems of racial, class, and other alterities, can form “the basis for progressive transformative coalition” and community through shared languages of difference and recognition. 12 For these artists, literature must not only tell a black queer woman’s story, but also re-present the bodies through which that story moves, and on which it makes its meanings.

“Conversations Intricate and Tactile”: Ntozake Shange’s “Two”

While Shange’s strategy of blending voice and body is perhaps most recognizable in the best-known versions of for colored girls, her choreopoetic thinking is evident both before and beyond the life of the Broadway production.

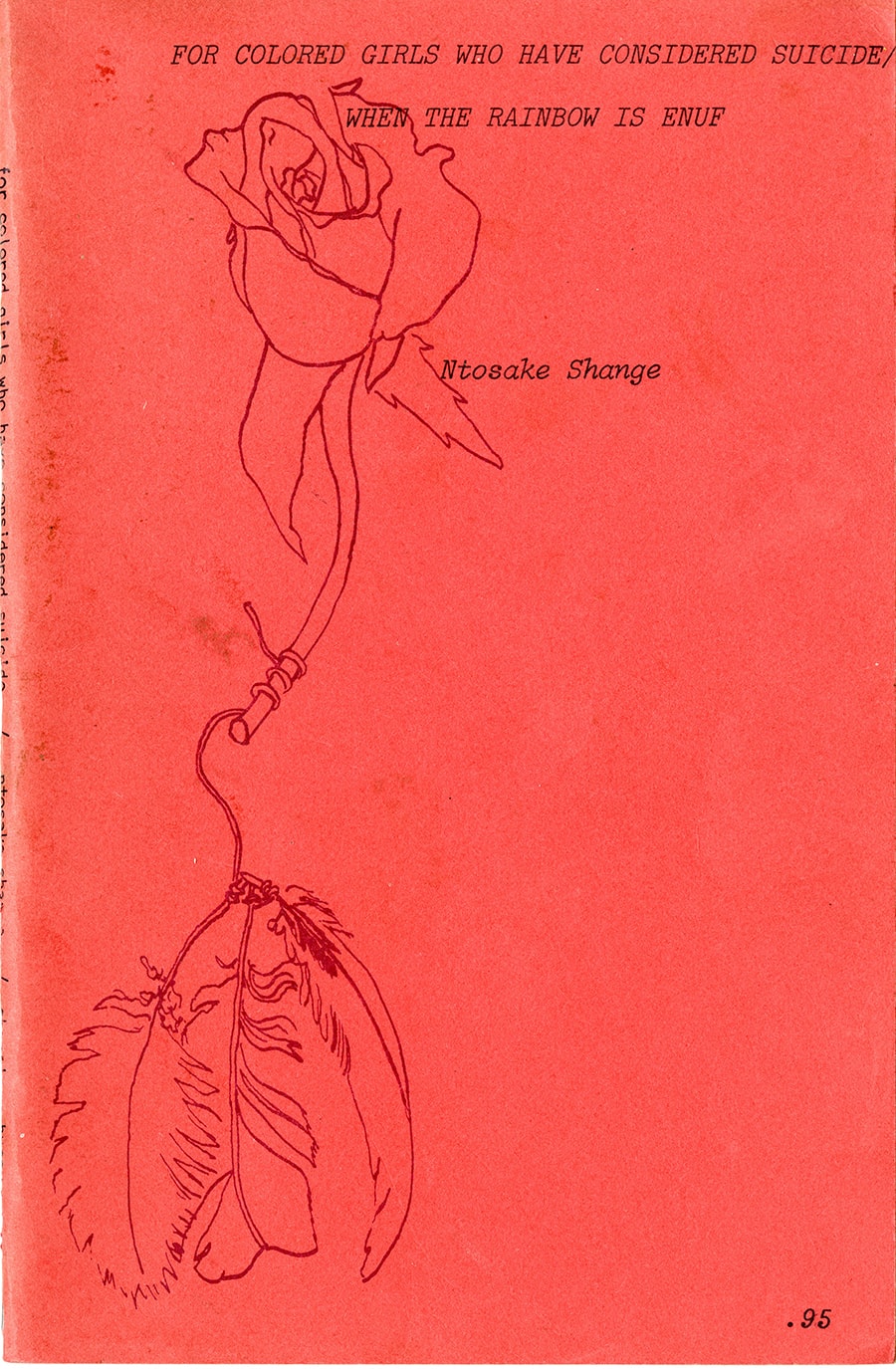

The poems collected in the chapbook version of for colored girls, published in 1975 by Shameless Hussy Press, chart the development of Shange’s choreopoetic thinking, both in for colored girls and beyond. As Alta Gerrey, Shameless Hussy publisher, notes, even before the poems’ publication, Shange preferred to perform the poems to music, always with “someone dancing” in the background. 13 This early emphasis on the body is evident in the front matter of the chapbook’s second edition printing, in which image of a black female body accompanies the text, indicating the place of black female embodiment in Shange’s poetry even before the emergence of the choreopoem as a form. 14

The poems, from which several sections of the choreopoem version of the text are culled, demonstrate the importance of embodied speech and expressive corporealities in Shange’s landscape of black female erotics. The collection’s second poem, a narrative piece titled “Two,” stands out as a particularly rich example. Dedicated to fellow poet and playwright Thulani Davis, “Two” tells the story of Graciela and Smoke, nonspeaking focal figures whose relationship illustrates the corporeal and sensory dimensions of black female language and communication. Early in the poem, the third-person speaker informs us that the women are so close to one another that “even when they spoke different languages/the voice was the same.” 15 Likewise, the unidentified speaker describes the intimacy between the two in specifically corporeal terms, explaining that “they never missed anyone else/ like they missed each other/ a deep hole crawled through all … marrow/ so they stayed round/ together/ most time the… thoughts they shared waz private.” 16 Smoke and Graciela’s relationship is defined by a same-sex intimacy that is erotic and corporeal, and that is facilitated by languages of both the body and the voice.

Shange echoes this embodied language of black female intimacy in formal properties of the poem. “Two” departs from Shange’s signature free-verse poetic style, taking on a prosepoetic stanza structure that uses minimal whitespace and literally fills the pages with the body of the text. This structure is underscored by the poem’s handling of dialogue. Although the text introduces Smoke and Graciela through metaphors of language and voice, the third-person speaker of never yields to their polyglossia; the figures’ speech is rendered only through indirect discourse embedded within the poem’s paragraph structure. The reader must thus work to excavate the women’s voices, and try in vain to disentangle those voices from the formal body of the text.

Nestled deep in the anatomy of Shange’s poetic structure, Smoke and Graciela’s voices—and their erotic connection—are most readily heard through languages of the body. The speaker gives us to understand that the two spend their time doing “what brought them secrets to cherish & purposes for rising at sunrise/ dancing & writin,” and that each woman shares stories about her many lovers with the other in “conversations intricate and tactile/ as whoever’s legs had been between hers.” 17 In this relationship, the simultaneity of language and movement in the joint practices of dancing and writing—the core juncture of the choreopoem form—also forms potential for a radical black female sensuality. It is through the women’s embodied languages—and in their “intricate and tactile” conversations about sexuality—that they divvy up the many sexual partners who approach them, seeking to sleep with both Smoke and Graciela at once. This endeavor always ultimately fails, the speaker informs us, because “choosin both smoke and graciela waz cosmically impossible.” 18

Despite the explicitly sensual dynamics of the women’s intimacy, the possibility of a shared erotic experience between Graciela, Smoke, and a third lover remains foreclosed until they encounter a figure who shares their understanding of the inseparability of body and voice. At the midpoint of the poem, the two attend a “ridiculous fete/jumbled with glitter boys” and “butch whacks.” 19 At the party, they encounter a “colored mimist… from mars” who redirects the poem’s narrative and opens new possibilities for black female sexual expression through embodied voice. Immediately, the three connect through the erotics of embodied voice: “graciela heard him talking & he was not talking/ smoke felt his heat & his hands were chill-damp.” 20 Graciela and Smoke sleep with the mimist, an act that has transformative implications for all three, leading to amalgamations of body and voice and broad-scale reconfigurations of both material and textual terrains. In erotic engagement, all three bodies become “… singularly muted language/… & the three of them/ smoke/ graciela/ & the mimist created so much energy/ they all thought they were walkin on the edges of the galaxy.” 21 This encounter establishes the queer reach of Shange’s choreopoetic thinking. Here, communication through both voice and body offers transcendent possibilities for articulating nuanced modes of black sexual expression; by becoming “singularly muted language,” Shange’s figures introduce the possibility of a queer space in which two deeply intimate black woman friends and “a colored mimist from mars” can create inroads into new galaxies of subjectivity and sexual connection. 22

- Ntozake Shange, Nappy Edges, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991) 3.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, See No Evil: Prefaces, Essays & Accounts, 1976-1983, (San Francisco: Momos Press, 1984) 20.[↑]

- Kara Keeling, “Joining the Lesbians: Cinematic Regimes of Lesbian Visibility,” Black Queer Studies, ed. E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005) 217.[↑]

- Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 15.[↑]

- Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 26.[↑]

- Canonical black feminist scholars such as Patricia Hill Collins, bell hooks, Michelle Wallace, and many others have explored the significance of stereotyping in understanding black female voicing. Perry, too, draws on Shange’s work to frame her interrogation of black female identity and voicing, subtitling her text “For Colored Girls Who’ve Considered Politics When Being Strong Is Enuf.” See Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).[↑]

- Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) 22.[↑]

- Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) 36.[↑]

- E. Patrick Johnson, “Feeling the Spirit in the Dark: Expanding Notions of the Sacred in the African-American Gay Community,” Callaloo Vol. 21, No. 2 (1998): 410.[↑]

- Cherrie Moraga, “Theory in the Flesh,” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, ed. Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa,(San Francisco: Aunt Lute Press, 1981) 93. The expressive technologies of color are central to Shange’s body/language as well. As Cheryl Clarke and others have pointed out, “color” functions in the choreopoem version of for colored girls as a crucial signifier of ethnic and racial difference within women’s communities. See Cheryl Clarke, After Mecca: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2005) 98.[↑]

- I situate choreopoetic thinking in relation to Shange’s work, not to center a US literary perspective as a progenitor of a queer African diaspora aesthetic, but to examine the overt and subtle ways in which queer diasporic poetics echo and connect across space and time. I read Shange as a focal point in this tradition because she has developed, named, and popularized a generic form—the choreopoem—that is useful in reading later queer diasporic formal innovations, many of which may be read as engaging directly or indirectly with her work.[↑]

- Cathy Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?,” Black Queer Studies, ed., E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005) 438.[↑]

- Alta Gerrey and Irene Reti, “Alta and the History of Shameless Hussy Press, 1969-1989” Regional History Project, University Library, UC Santa Cruz, 1 January 2001.[↑]

- The composition of this sketch also evokes the iconic cover illustration of the Scribner edition of the choreopoem, painted by Paul Davis.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf, (Berkeley, CA: Shameless Hussy Press, 1975) 2.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf, (Berkeley, CA: Shameless Hussy Press, 1975) 3.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]

- ibid.[↑]