Two covers in 1997 explicitly explored race in sport. In the first issue (Vol. 87 Issue 23) the headline reads, “What Ever Happened to the White Athlete?” which is superimposed over a classic black and white picture of four posed, clean-cut players in white uniforms from a boy’s basketball team in the fifties. The next issue, published just a week later, is starkly different. The cover is entirely black with a large block of white text. The only picture is a small photograph of Latrell Sprewell, clearly emotional and implicitly dangerous. The text reads:

Latrell Sprewell has been publicly castigated and vilified, and any player who gets a similar urge to manually alter his coach’s windpipe will surely remember Sprewell’s experience as he acts on that impulse. Problem solved. But the Sprewell incident raises other issues that could pose threats to the NBA’s future, issues of power and money and – most dangerous of all – race . . ..” (Vol. 87 Issue 24).

The cover viewed in isolation raises its own problems, but in contrast with the previous week a telling story of race emerges. 1 No one would condone Sprewell’s volatility, which led him to attempt to strangle his coach, P.J. Carlesimo, during practice while playing with the Golden State Warriors. There was much argument in the national media on whether Sprewell had been a victim of racism given his one year suspension from the game and the fact that Carlesimo was not held accountable for his well-documented, constant, and vile verbal assaults on a series of players, not only Sprewell. 2 Juxtaposing these two covers, we see the first as implying that race is dangerous to white athletes and to the world of sports in general, and the second declaring that angry black man are dangerous, period. There’s no suggestion that racism is the problem.

In her essay included in this issue Karla FC Holloway sees a similar situation in the recent controversies at Duke University involving the alleged rape of a black woman by members of the Duke Lacrosse team (which first received mention in a corner of the June 26, 2006 cover, over three months after the allegation first appeared in the news). Again, race is dangerous, here to the culture of the University, but not necessarily to “those members of a class who have been exposed to abuse or intolerance or inequity (on this campus, as in the nation, women and black folks).” In a recent New York Times column, Harvey Araton makes an explicit connection between the Duke controversy and the Latrell Sprewells and Allen Iversons of professional sports:

Somehow, what ZIP codes the players’ families live in, what high schools they attended, what they wear and, yes, the color of their skin are supposed to be clues as to why they developed reputations as devilish Dukies, and why two or three could end up in jail. Sound familiar? It’s the same character trial-by-appearance and cultural typecasting we get when the finger of the accuser points to the African-American male with tattooed biceps and cornrows. 3

Holloway would agree that cultural perceptions of those involved are at work in the perception of guilt and innocence in both instances, but she also points to a crucial difference: in the case at Duke the characterization of the players as white implies their innocence – and thus the guilt of the black woman accusing them. Black innocence is never an option.

The Sports Illustrated covers play out the logic of a racism which renders black men always already dangerous and black women always already guilty. What ever happened to the white athlete? What about that Latrell Sprewell? Who is guilty and who is innocent in the Duke case? When we juxtapose the cover picturing the young white men and their basketball from the 1950s with the starkly black cover with the small photo of Sprewell, what are we to think? Are we supposed to long for a time when interracial teams were against the law in southern states, or when black athletes faced discrimination on and off the field or court? Of course not, but the subtext of race says otherwise, suggesting a racism unspoken yet legible on the covers.

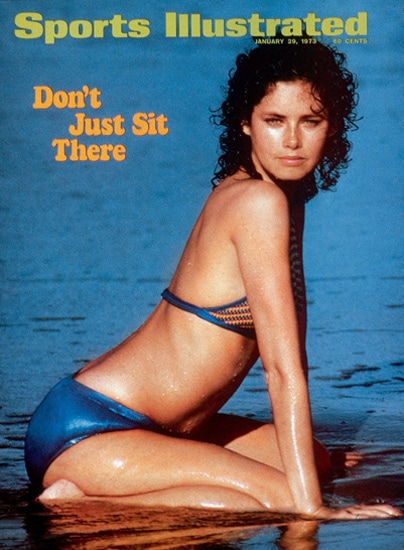

SI‘s ambivalence over race and racism has been apparent not just in its representation of Black men and danger, but also in its ambivalence over Black women and sexuality. If white women are first and foremost presented for their sex appeal, SI has had much more trouble representing Black women as sexual at all. This came to the fore most famously in a controversy over covers of the swimsuit issue, the point at which the most women are represented and the point at which it was particularly hard for SI to include Black women or any women of color. The history of the swimsuit issue is much discussed, but it is a crucial aspect to the representation of both race and gender in SI. The swimsuits seen in recent years are clearly not suitable for competitive swimming, but the first swimsuit issue was arguably the third issue in the entire history of the magazine, part of the magazine’s early representation of amateur sporting. While SI does not consider this the first swimsuit issue (it ‘officially’ started in 1964) it is the first cover on which a woman appears wearing a bathing suit (and in this case a bathing cap as well). 4 The swimsuit issue, always considered controversial, has not always featured the skimpily clad women we expect to see today. The women have been shrinking and the clothes have been disappearing. The swimsuit model for 1965 (Vol. 22 Issue 3) has a surprisingly normal body and wears a one piece. In 1969 (Vol. 30 Issue 2) she wears a skirt over her bikini, and in 1970 (Vol. 32 Issue 2) she actually wears a sweater. The turning point seems to be in 1973. The model, Dayle Haddon, looks seductively at the camera, sitting rather provocatively in the water and wearing a metallic blue bikini. The headline reads, “Don’t Just Sit There.” One must question if the reader expects her to stand up and play a competitive game of beach volleyball. We cannot know, but we do know that many copies of this magazine were sold to see her “just sitting there.”

- Time Magazine‘s digitally altered June 27, 2004 cover comes to mind, as an image that undoubtedly raises its own problems. Here O.J. Simpson’s mug shot was intentionally darkened, intensifying a sense of danger and thus implying an assumption of guilt, solely through visual representation. Guilt is inextricably linked with race. For further discussion of race and the O.J. Simpson case, see, Birth of a Nation’hood: Gaze, Script and Spectacle in the O.J. Simpson case, Toni Morrison and Claudia Brodsky Lacour, eds. (New York: Random House, 1997).[↑]

- A year later the Sprewell incident would return to the news when Kevin Greene, a football player for the Carolina Panthers attacked his coach on the sidelines of a nationally televised game. Greene, a white man, received a one game suspension. While the incidents were undeniably different (Sprewell came back for a second meditated attack), a black man attacking a white coach lead to a one year suspension and a public roasting that continues today, while a white man attacking a white coach resulted in a slap on the wrist and a relatively mild media outcry, and an even milder response from the public.[↑]

- Araton, Harvey. “Indulging Athletes Isn’t Class Matter,” The New York Times. 21 April 2006, late final edition: D1.[↑]

- For a detailed analysis of the Swimsuit Issue, see Laurel Davis, The Swimsuit Issue and Sport: Hegemonic Masculinity in Sports illustrated (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997).[↑]