If sport so fundamentally defines gender for (at least some members of) U.S. society, what impact does the representation of women athletes have on this definition? And perhaps more to the point, if the cover of Sports Illustrated regularly included women who were athletes first and sexual second, how would the gender relations encapsulated by this anecdote have to change? Would the vision of women who might in fact be able to take a hit from Ronnie Lott change the meaning not just of femininity but of masculinity? Would it open the door to women who could, unlike Atalanta, afford to bypass the apple and win the race (whether on the athletic field or in other areas of competitive accomplishment in our society)? The question here is what do strong images of female athletes actually accomplish? If the mere existence of a powerful athlete like Ronnie Lott can construct masculine identity, can an image of a powerful athlete like Lisa Leslie construct an identity for women? Do images of competitive and athletically competent women have the ability to enact social change that exceeds the boundaries of the world of sport?

These questions are so important because SI is not just a medium for entertainment. SI is also a journalistic enterprise, part of Time, Inc. one of the most highly respected and powerful sources for news in this country. And so, there is good reason to be concerned that the pictures provided by SI help to construct the facts about women, men, and our society. But, as with almost all news outlets in the United States, SI is a for-profit enterprise. And so we have to ask, would people – men or women – want to buy a magazine that consistently challenged gender norms? If SI is, however, in the business of images then we need to think about the ways in which this business shapes the representation of both gender and race. It seems clear, for example, from the cover with Jennie Finch to the types of photos we see of tennis players like Anna Kournikova and Maria Sharapova that SI thinks that sex sells. Moreover, when it comes to women, the sex that really sells can even be detached from athletic accomplishment. Kournikova became an icon in the pages of SI without ever breaking through to the very top ranks of her sport. Part of her popularity seems to be founded in the fact that she has not been entirely successful on the court, or at the very least her lack of success is negligible in relation to her level of popularity.

The impact of the market on the reporting of sports has not just been through the need to sell magazines and the perceived means of doing so. A major reason for the decline in women’s representation is the change in what one considers ‘sport.’ In SI‘s first years women were featured swimming, riding horses, skiing, doing gymnastics and archery, even playing chess. Sports were open to amateurs. You did not need to endorse the products of a corporation or have a multi-million dollar contract to appear on the cover of a major sporting magazine. As the sports world becomes more closed off, with coverage of basketball, football and baseball comprising the majority of sports media, it becomes more closed off than ever to women. While there is no professional baseball league for women (there is for football though it never appears in the media), there is a successful professional basketball association for women, the WNBA. There has, however, never been a WNBA player on the cover of Sports Illustrated, not even in its inaugural year, 1997.

The only two women to appear on covers in 1997 were Venus Williams (professional tennis players have fared relatively well in SI, and are likewise the highest paid female athletes) and Jamila Wideman, a basketball player for Stanford who appeared next to her father, John Edgar Wideman, an author and college basketball star himself. Jamila Wideman is one of only four female college athletes to get the cover shot on SI (excluding the five covers in nine years that included college cheerleaders). The other three are Cheryl Miller (1985), Jennifer Rizzotti (1995), and Diana Taurasi (2003), all basketball players. In contrast, from 1954 to 2004 male college athletes have been on an average of 8 covers per calendar year, with the month of March almost exclusively dedicated to college basketball.

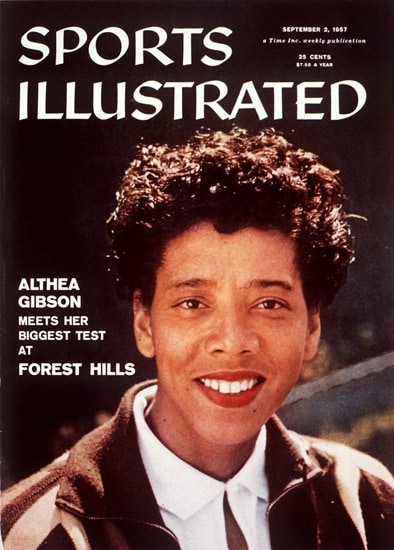

Jamila Wideman can also consider herself one of sixteen women athletes of color ever to be on a cover of Sports Illustrated Magazine. The first woman of color, Althea Gibson, was featured in 1957. A full twenty-one years later, golfer Nancy Lopez made the next appearance. Others include Venus and Serena Williams, Marion Jones, Gail Devers, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Florence Griffith Joyner, Michelle Kwan, Kristi Yamaguchi, Cheryl Miller, and three members of the 1996 U.S. Women’s Basketball team.

When it comes to men of color, the issue is not under-representation. In that same year that readers encountered Jamila Wideman on the cover, they also saw thirty-one covers portraying men of color, from Tiger Woods and Evander Holyfield to Jerome Bettis and Alex Rodriguez. Sport is one of, if not the only, realm in U.S. popular culture where men of color are not under-represented, and this representation is again determined by the nexus of business and sex. The one time the magazine directly brought up the issue of race, the trope was not that of accomplishment, but of “danger.” The type of “danger” associated particularly with African American men in U.S. society, is a danger that is often sexualized. And, when it comes to women of color, we see few photos of African American women in a society which is famously ambivalent about African American women’s sexuality. 1

- For more discussion of Black female sexuality, see, for example: Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, and Class (New York: Vintage, 1993); Hortense Spillers, “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words,” Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, ed. Carole Vance (New York: HarperCollins, 1993); and Evelyn Hammonds, “Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 6, nos. 2-3 (1994): 126-145. And for more on Black masculinity and sexuality, work includes but is not limited to: Patricia Hill Collins, Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism (New York: Routledge, 2004); Representing Black Men, Marcellus Blount and George P. Cunningham, eds. (New York: Routledge, 1995); and Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America, Richard Majors and Janet Mancini Billson, eds. (New York: Touchstone, 2002). [↑]