Beatie’s Affective Labors

In light of these complex connectivities, it is also important to take from Chou’s work on tongzhi politics a sense of how flexible the so-called neo-Confucian social-familial system might actually be in its mediation of the state’s desire for certain kinds of citizen-subjects or modes of sexual alliance. In the US context, for instance, the concept of queer or trans kinship cannot be invoked now without mention of Thomas Beatie, whose identity as the “pregnant man” has been shaped according to municipal laws in three states: Hawaii, where he transitioned and obtained government-issued documents reflecting his current gender; Oregon, where his admission records to the hospital where he gave birth to his three children consistently read “male;” and most recently Arizona, where a judge in March refused to grant Beatie a divorce from Nancy, his wife of nine years, because he retained his female reproductive organs at the time of their marriage.

Indeed, the disciplinary forces that contribute to an apparent asymmetry between transmasculine and transfeminine experience in the realm of trans citizenship seem themselves related to long-standing practices of state control over bodies with gestational capacity and to ongoing popular movements for reproductive rights. As Renee Tajima-Peña discusses elsewhere in this issue, a (recent) history of eugenic sterilization has had a distinct impact on racialized practices of kinship in the United States, but it is striking how rarely the topic of forcible SRS enters into public discourse about trans identity or trans kinship in the Global North. As shown by mainstream films like Transamerica (2005) or documentaries like Transparent (2006) that explore family relationships after a parent has transitioned, the opposite is more frequently true.

In his memoir, Labor of Love (2008), however, Beatie broaches the topic when discussing his own gender transition:

I also chose to keep my reproductive organs. Some transgender men opt to have them removed, believing they need to sterilize themselves to be considered a different gender. But I didn’t feel this way at all. In fact, I couldn’t help but wonder about the logic: How could having no reproductive organs make someone any more or less a man or a woman? It just makes you sterile. Thankfully, there are no state-sponsored sterilization requirements for transgender people, and I had no desire to opt out of the possibility of procreating.34

Beatie invokes a very specific notion of the state as a Hawaiian-born US.citizen, but he offers an expansive redefinition of the human when he reorganizes gendered forms of reproductive agency around a new binary: sterile or fertile. His ability to think of his gender identity as separate from either his gestational capacity or his hormonal gender is what enables him to identify as his own “surrogate—to use my own body to go through this process, and not someone else’s,” he writes.35 It also takes the irony out of his self-appellation as the pregnant man, since he would claim first to be a fertile subject in possession of his reproductive organs and, secondly, a self-fashioned man who, in some of the most fascinating sections in Labor of Love, actively disassociates himself from his Asian father.

Beatie has been criticized, along with Nancy, for allowing the media to sensationalize their story—exclusive interview rights went to Oprah Winfrey and People magazine rather than to the LGBT press who ended up being their “biggest disappointment”—and for failing to acknowledge the existence of countless transmasculine-identified individuals who have also given birth to biological children in mainstream medical settings.36 The signal difference, for Beatie, came from working closely with Oregon hospital officials who pledged to honor his gender identity at admissions: “Never before in history has someone delivering a child had the letter M typed on their wristband.”37 While Beatie stopped taking testosterone in order to become pregnant, Nancy (who had undergone a hysterectomy years before) elected to put herself on a hormone therapy regimen in order to boost her maternal capacity to breastfeed each of their three children.

Beatie’s confident navigation of the media and implicit faith in the law were both tested, however, when a video capturing one of Nancy’s “violent rampages” was leaked to the celebrity tabloid outlet TMZ in May 2012. In broad strokes associating her with a domineering white masculinity, Nancy is described as having a substance abuse problem (in the opening moments, Nancy is shown passed out on the floor) and as “manhandling” the children in the video, “beating” her husband, and destroying the family computer. Beatie’s voice bickers, rages, and sobs as he remains steadfastly in control of the surveillance technology of the camera, seemingly gathering the evidence he needed to launch divorce proceedings against Nancy, as he did less than a year after the filming.

Video 3: Video exclusive posted to TMZ.com in May 2012.

In March 2013, Beatie lost his divorce case in a family court in Arizona, where the family reportedly had moved in order to be closer to relatives, due to this finding by the judge:

The decision here is not based on the conclusion that this case involves a same-sex marriage merely because one of the parties is a transsexual male, but instead, the decision is compelled by the fact that the parties failed to prove that (Thomas Beatie) was a transsexual male when they were issued their marriage license.38

While Arizona does uphold a ban on same-sex marriage, the court’s opinion reveals that the actual legal problem here is posed by the uncertain definition of female-to-male transsexualism. The specter of forcible SRS emerges in the judge’s invocation of Beatie’s failure to prove that he had renounced his gestational capacity when he married Nancy. Although he completed gender confirming surgeries in 2012, Beatie’s ongoing fight in this conservative state for custody of his three biological children—who are multiracial individuals, as he is—he must continue to articulate a standard of parental fitness that elevates his unique kinship capabilities over those of his white partner. The issue of Beatie’s former fertility, which did not conflict with his gender identity either in Hawaii or Oregon, therefore seems spectacularly caught up in Arizona’s deployment of overt racism in two of its own high-profile pieces of state legislation: HB 2281, which bans the teaching of ethnic studies in schools, and SB 1070, which supports systematic racial profiling in the name of US border control.

Although Beatie’s racial identity was initially overshadowed in the media by his identity as both father and surrogate to his children, I want to suggest that it is precisely his racialized practice of kinship that has made him so famous. In fact, his multiracial heritage is central to his articulation of transmasculinity in Labor of Love, and his memories of his parents reflect a racial as much as a gendered dichotomy.

My father, with his broad shoulders and his round biceps and his jet black hair and the green jade ring he always wore, large as a Spanish olive, and the thick fold of hundred-dollar bills he always kept in his wallet, and the strong clean smell of aftershave that went with him everywhere, and the dark, glazed, glaring eyes that never smiled even when he did. My father was a larger-than-life figure to me, at first an all-powerful king, a builder of castles, and then a sort of monster, menacing and impossible to defeat—sort of like the troll beneath the bridge.

Conversely, my mother was the hero of my story, fair and good and beautiful. She was born in Minnesota, and her blond hair and pale skin contrasted with the features of Hawaiian women, and with those of my half-Filipino, half-Korean father. It was easy to see her as a force of light, and my father as an agent of darkness.39

Beatie, who took his mother’s maiden name as his own surname when he transitioned, remembers only one clear instance of being angry at her—when she joked with a friend that her daughter’s nose was flat, like her father’s. After she committed suicide when Beatie was 12 years old, he maintained a tense relationship with his distant and sometimes abusive father, the child of a Filipino laborer and a Korean mail-order bride, who “made it out of the slums of Kalihi” to become a successful architect.40 Beatie’s near-worship of his mother seems to feed off her all-American image and pedigree: “Benjamin Harrison, twenty-third President of the United States, was my mother’s mother’s father’s mother’s father’s brother,” he states in a tongue-in-cheek moment.41 However, his meticulous attention to the accoutrements of his father’s own multiethnic masculinity in this passage—which immediately brings to the surface the feelings of abjection that he associates with this particular gender identity—suggests that it is the loss of his father which Beatie attempts to confront through his own melancholic gender formation.

This desire both to preserve and to destroy his father’s image, the desire to manage the Oedipal resolution well, is powerfully evident in the moment that Beatie chooses to come out to him as trans. Surprised by an unexpected visit from his father shortly after undergoing top surgery, Beatie recalls:

I was gagging on the words, trying to gather a few that might make sense, anything besides “surgery” and “transition” and “gender reassignment,” hard, clinical words that would bruise my father like blunt objects.

But there were none. And so I reached down and grabbed the hem of my T-shirt and pulled it over my head in one quick movement. I could already see my father’s expression as I pulled the shirt over my head. Even without glasses he could see the twin red crescents on my chest, my surgical scars, longer and brighter than I had hoped, inescapable testaments to what had happened. He could surely see that my breasts were gone, and that my chest, thanks to testosterone injections, had gained musculature and definition. He could see that his little girl was now a man.

“What are you doing?” my father stammered as I pulled up my shirt. And then a small, guttural gasp.

“My god, Tracy, what have you done?”

I stood there and let him take it in […] But what he said next surprised me.

“You look,” my father said, “like me.”42

Beatie senses the violence that a language of biomedicalization would inflict on his father’s racial, gendered, and class subjectivity, but he cannot predict this willing and intimate recognition of his transmasculinity. Without any words at all, in fact, Beatie displays his new state of embodiment in a disrobing gesture that proves “his little girl was now a man,” and not just because men have muscled chests—as both Beatie and Nancy had trained as female bodybuilders. Rather, Beatie describes in this passage how the bared breasts that would have drawn the father’s incestuous gaze—“I stood there and let him take it in”—have been transformed in a way that restages the primal fantasy of (racial) castration.43 Beatie’s long and bright surgical scars initiate him into the very relation to lack that defines masculinity as that which has something to lose, and his father in turn confers upon Beatie the identity—borne of similarity—which signals the latter’s initiation into Asian masculinity and, more importantly, Asian fatherhood.

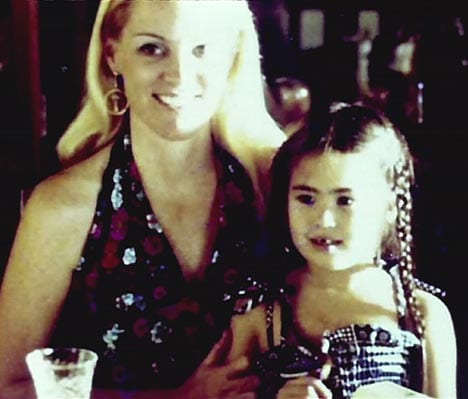

In the year since his marital problems were made public, Beatie has been increasingly hailed as a queer and multiracial Asian Pacific Islander American spokesperson. The Asian American identity-in-formation that I, too, claim for him here depends not on a single or evident axis of identification, i.e., race, but rather on Beatie’s own performance of trans postcoloniality. Currently, this performance entails exercising his legal right to a social-familial system in which a daughter can become a father—and to a system of fatherhood also different from what his own multiracial parent showed him—and, ultimately, as this picture of Beatie’s affective labor proves, to entirely new ways of sharing trans kinship.

- Thomas Beatie, Labor of Love: The Story of One Man’s Extraordinary Pregnancy, (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008): 162. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 305. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 254. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 4. [↩]

- See http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/29/pregnant-man-judge-reject_n_2979968.html. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 15-16. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 17. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 18. [↩]

- Beatie 2008: 166. [↩]

- See David L. Eng, Racial Castration (Durham: Duke UP, 2001): chapter 3. In this scene from Labor of Love, Beatie’s scars are interpreted by his father as a sign of invulnerability, which reproduces the condition of Asian masculinity as an identification with a phallic power that is nonetheless not there to seen. [↩]