A response to the panel “Using Knowledge, Advancing Activism” at the conference Activism and the Academy: Celebrating 40 Years of Feminist Scholarship and Action. Watch the video here:

I was asked to offer some brief reflections on the panel, “Using Knowledge, Advancing Activism,” one of the many thoughtful and provocative sessions featured at the Barnard Center for Research on Women’s (BCRW) conference, “Activism and the Academy: Celebrating 40 Years of Feminist Scholarship and Activism.” 1 The mood at the conference was a generative combination of excitement and grief. On one hand, we were honored to be part of the fortieth-anniversary celebration of such an important feminist organization, one that continues to facilitate the kind of field-shaping, bold work that their earlier gatherings produced—not least of which was the 1982 Barnard Sex conference. 2 But, on the other hand, the conference began just two days after the execution of Troy Davis, and there was much rage, sadness, and disbelief that the Supreme Court refused to stay the execution despite the abundantly clear lack of evidence about Davis’s guilt. 3

I mention the Davis execution not only as a way to remind us what was foremost on our minds that weekend in 2011, but also because it relates to the conversations that took place on the panel that I now want to think about—conversations that, with lesser and greater degrees of optimism, revolved around the relationship between knowledge, power, and social change. “Using Knowledge, Advancing Activism” featured three speakers: Rinku Sen (Colorlines, Applied Research Center) 4 ; Jamia Wilson (Women’s Media Center) 5 ; and Dean Spade (Sylvia Rivera Law Project; Associate Professor at Seattle University School of Law). Two of the panel’s guiding questions were:

- How can activists use knowledge to advance their campaigns?

- How can scholars and activists work collaboratively to produce and promote knowledge that is grounded in feminist and social justice frameworks?

The BCRW organizers are thoughtful about how they structure their events, and this panel was no different. The moderator, Laura Flanders (The Laura Flanders Show), opened with some important epistemological questions, asking the audience and the panelists to consider what counts as knowledge, who counts as experts, and whose knowledge matters. And she was a great facilitator, working to make the session into a conversation, rather than a set of discrete presentations, inserting her own thoughts and feelings as a feminist journalist and broadcaster throughout.

One of the things that I most appreciated about the panelists is that each avoided creating a dichotomy between theory and practice, and between knowledge and activism. Even when Flanders asked, “Are there places where knowledge and activism butt heads?” the panelists did not take the bait. Wilson in particular complicated the traditional academic boundaries placed around knowledge when she talked about her grandmother’s intelligence:

My first real awareness, too, of the importance of getting stories out there came from my grandmother, who up until recently was a domestic worker and she … did not graduate from high school but is one of the smartest, most brilliant people and theorists that I know. And … that she gained a lot of her understanding of what was going on in the world based on the media, and was able to apply her version of critical analysis, which is very different than the one that you’re taught in school … really exemplified for me that media is the strongest public education tool. (13:52—14:34)

Similarly, Sen situated her investment in journalism and research as an effort to popularize racial justice by helping people move back and forth between information, emotion, and action. The affective piece of this was an important aspect of Sen’s presentation which in large part emphasized that data alone does not have the power to move people to change their minds and act. Rather, she argued that information should be conveyed to the public through narratives rich with settings, imagery, characters, metaphors—stories that can powerfully challenge our habitual frames for understanding the world. If data or information in itself is not likely to be transformative, neither is depression, Sen argued, because it prevents people from moving.

Both Sen and Wilson, then, called for—and definitely performed—optimism about what the production of knowledge geared toward social justice can do in the world. If narrated through affective, narrative registers; if disseminated widely to and through publics; if inclusive of organic, spiritual, instinctual, experiential, or, in short, standpoint epistemologies—then information and research can empower communities; disrupt business as usual; and, perhaps most importantly, persuade people to change their minds.

Spade took a different angle to the conversation by questioning our faith in a series of progress narratives whose dominance has a grip on even leftist organizing: that things are getting better through the forward march of time; that the law sets people free; that more and better knowledge and research will lead to social change; and that the university classroom can be a site of transformation. The institutions (or complexes, as Spade would likely call them) that help to produce and reinforce these narratives are also those that produce suffering in the world, he argued. Most central to the panel’s topic was Spade’s critique of our efforts to produce social change by creating more and better information that we think should persuade publics or courts of law. This argument certainly had resonance for me in relation to my local, Arizona context, where, as Curtis Acosta—one of the teachers in the Tucson Unified School District who formerly taught Mexican American studies before the program was shut down by HB 2281—has said, “the truth doesn’t matter in our state.” I would also add that the Davis execution is another good example of how more and better information and arguments too often fail to achieve justice when the institutions involved are designed through and through to protect the state’s interests.

I also take our faith in the kinds of narratives Spade questioned to be related to what Lauren Berlant has so compellingly described as “cruel optimism,” in the sense that “the very vitalizing or animating potency of an object/scene of desire contributes to the attrition of the very thriving that is supposed to be made possible in the work of attachment in the first place” (21). 6 However, Berlant and Spade are both deeply committed to imagining and building other worlds. For Berlant, the inevitable disappointments and failures we experience under contemporary capitalism and in our social-movement work can be generative for world-building:

I think that everything that’s disappointing is accompanied by forms of refusal to be resigned to normative fantasy. And I do think it’s the job of writers and critics and artists and everyone to create better objects for better fantasies—which is to say objects that offer the possibility of less cruel-optimistic relations.” 7

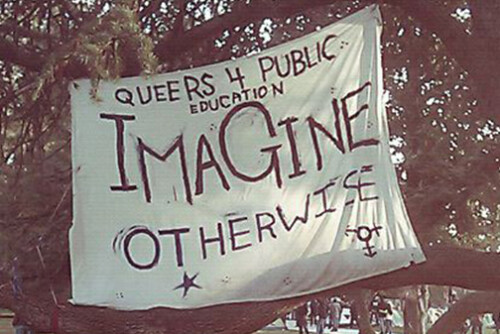

Likewise, for Spade, what is needed is a robust imagining of what seems unimaginable, and the deliberate creation of the kind of spaces that allow such imagination to flourish. In particular, Spade called for a world free of the deeply internalized concept of exile. Such a transformation would need to operate across all scales, from the interpersonal conflicts within social-justice organizations to the immigration policies of nation-states. Such a transformation, he argued, would be necessary for living in a world without prisons, and without policed national borders. 8 It would also demand a different set of strategies and sites than those that are most available and habitual to us. For instance, rather than expecting the university classroom to be a site of transformation, he advocated freedom schools and reading groups—nonhierarchical spaces in which participants could move through a curriculum while being open (and able) to being challenged about their own commitments to white supremacy and other forms of violence. Further, rather than accepting the professionalization of social justice, he called for the kind of strategies used by the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, such as nonhierarchical structures, flat pay scales, and genuine community involvement in which the most useful knowledge is not the lawyers’ knowledge, but that of the people who have been most harmed by their daily negotiation of intense spaces of racialized gender violence.

If we take Spade’s point that we need to let go of our attachments to familiar fantasies about how social change will happen, because they turn out to be cruel, then what are we left with? Does the optimism about creative communication of truths offered by Wilson and Sen hold up? In some modified form? Could it be combined with the emphasis in Spade’s talk and in Berlant’s work on creative imagination of alternative objects and scenes of attachments that might be less cruel? Can the grief and disappointment that we felt that weekend, and that we continue to feel about Davis’s execution and Oscar Grant’s killing and Trayvon Martin’s and Reneisha McBride’s and the shutting down of the TUSD Mexican American Studies Program and…—can our grief and disappointment themselves be an affective mobilizing force that can disrupt the disassociation between feeling and thinking, and between thinking and acting, and help us to imagine and work toward new worlds, changing the way that we relate to each other, and even to ourselves?

- I feel very grateful to the organizers and participants of the Activism and the Academy Conference, held on September 23-24, 2011. I found the weekend to differ radically from conferencing as usual. It was rejuvenating, challenging, and memorable. So, even though my comments focus on one panel, I am holding several threads in mind from the couple of days at Barnard. Thanks also to Catherine Sameh for inviting me to contribute this short piece for The Scholar & Feminist Online.[↑]

- See the important anthology that came out of this conference: Carole S. Vance, ed, Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984.[↑]

- In 1989, Davis was convicted of killing a police officer/security guard outside of a Greyhound bus station in Savannah, Georgia. Witnesses later rescinded their identification of Davis.[↑]

- The name has since changed to Race Forward.[↑]

- Wilson is now with Youth Tech Health[↑]

- In “Cruel Optimism,” Lauren Berlant notes that what is distinctive about cruel optimism is, for one, that it is “the condition of maintaining an attachment to a problematic object in advance of its loss.” The ongoing attachment to the object of desire wears out the subject who longs for it. I also understand Berlant as arguing that those with the least access to resources under contemporary capitalism have the most difficulty with this attrition. See Lauren Berlant, “Cruel Optimism,” differences, 17.3 (2006): 21.[↑]

- David Seitz, “Interview with Lauren Berlant,” Society and Space open site 22 Mar 2013. See: societyandspace.com/2013/03/22/interview-with-lauren-berlant.[↑]

- During her January 19, 2012 presentation at the University of Arizona, “A Borderless World,” Gayatri Spivak also spoke of the need for creative inquiry in order to create an educated electorate with the will for social justice. She called for “inculcating democracy as a habit.” For Spivak, as for Spade, creative inquiry stretches the political imagination. See also Gayatri Spivak, “What is to be done?,” Tidal Sept 2012: 2, 4—a piece she wrote about and for Occupy Wall Street. Here she also discusses the difficulties of “the building up of a will to social justice generation after generation.” For Spivak, this building depends on education, especially at the post-tertiary level, and, “It is not a question of subject matter alone, nor of gathering information. It is a question of making minds that will read the information right. It is a question of educating in such a way that the intuitions of democracy and justice for everyone becomes habitual, not just self-interest: working for standards not necessarily motored by competition; not being rewarded for leadership; not encouraging role models; one could go on. … The electorate must learn to read well enough, generation by generation, so the play of metaphors is seen clearly.” See sidneyjgluck.com/2012/09/13/gayatri-spivak-in-occupytheorys-journal-tidal.[↑]