From Birmingham, Alabama to Antwerp, Belgium, the recent removal and defacing of monuments to Confederate and imperialist leaders has marked the most recent wave in our long-lasting stream of struggles over haunting legacies. Some believe that removing these statues is an attempt to erase or cover up history. For others, it represents a means to confront violence, racism, and oppression in history and in the present. This brief reflection addresses identity politics intrinsic to the process of building new monuments today, pointing to the possibilities and limits of art to facilitate social change. I will approach this reflection through the lens of a recent public art commission for a monument commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which I won, but withdrew from before anything was built.

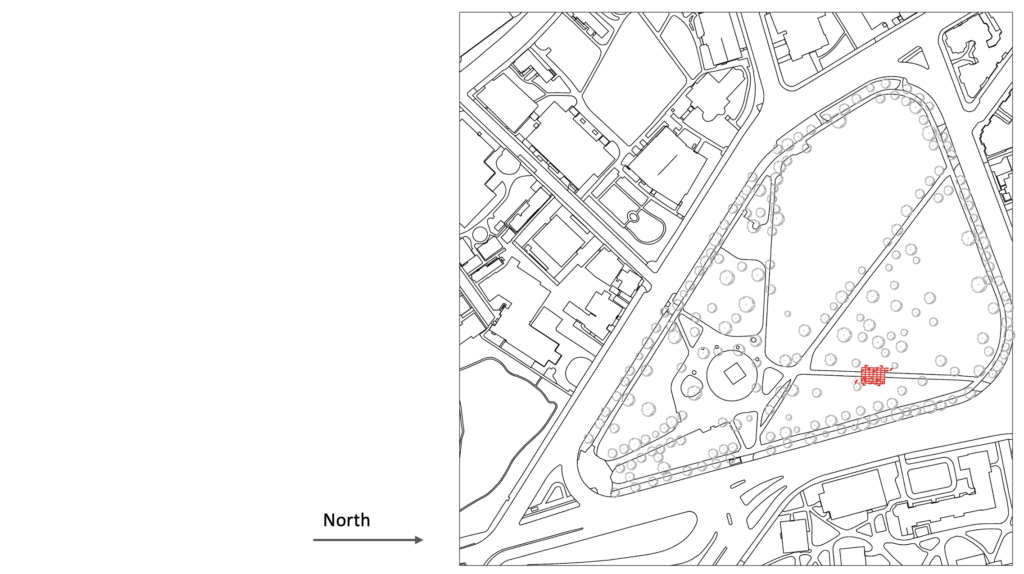

In November 2019, I received an email from the Director of Public Art and Exhibitions notifying me that I have been selected as one of four finalists for the Cambridge Nineteenth Amendment Centennial public art project. This art competition had been initiated by the City of Cambridge to commemorate Cambridge Suffragettes with a new public artwork to be constructed on the historic site of the Cambridge Common.

While I had not submitted a Request for Qualifications following the City’s public call for proposals, I was excited to learn that I had been shortlisted for the commission. The four finalists – Harries Heder, Merge Conceptual Design, Nora Valdez, and myself – had been selected based on our experience in public art evidenced in portfolios found at the City’s artist database. The four finalists were invited to site visits and a “community meeting” held on 12 February 2020, during which Cambridge residents had the opportunity to share their varied perspectives and questions related to the project and the site. This public gathering was an important event for many reasons, but most importantly because it provided an opportunity for voicing critical questions and different viewpoints regarding the subject of commemoration, as well as exchanging creative ideas on how the ongoing political climate should be approached. The many citizens of Cambridge who were present at the meeting made it very clear how passionate they were about the history of the Suffrage Movement and the future of democracy in America. Some community members criticized the fact that no Black artists had been shortlisted for the public art commission. Others were concerned about the choice of site designated for the project, as the historic park of the Cambridge Common is already crowded with public monuments and alternative sites might have been more suitable. Both concerns had been previously debated in various stages of the process and the decision for the site and the shortlisted artists had already been made at this point.

This public feedback, along with an elaborate information package prepared by the Public Art and Exhibitions department of the City of Cambridge, paved the way for the development of the four shortlisted project proposals. The shortlisted artists were tasked with conceptualizing a way of commemorating Cambridge suffragettes and their decades-long struggle for women’s rights and equal responsibilities of citizenship, while offering a critical response to the specific moment in time when the very same voting rights were under severe threat of becoming abolished for all Americans.

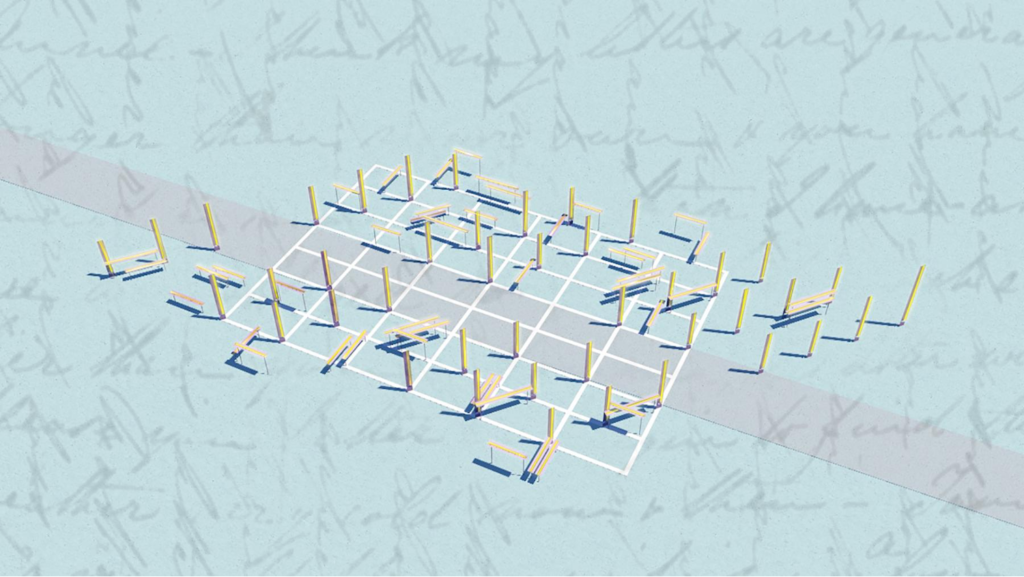

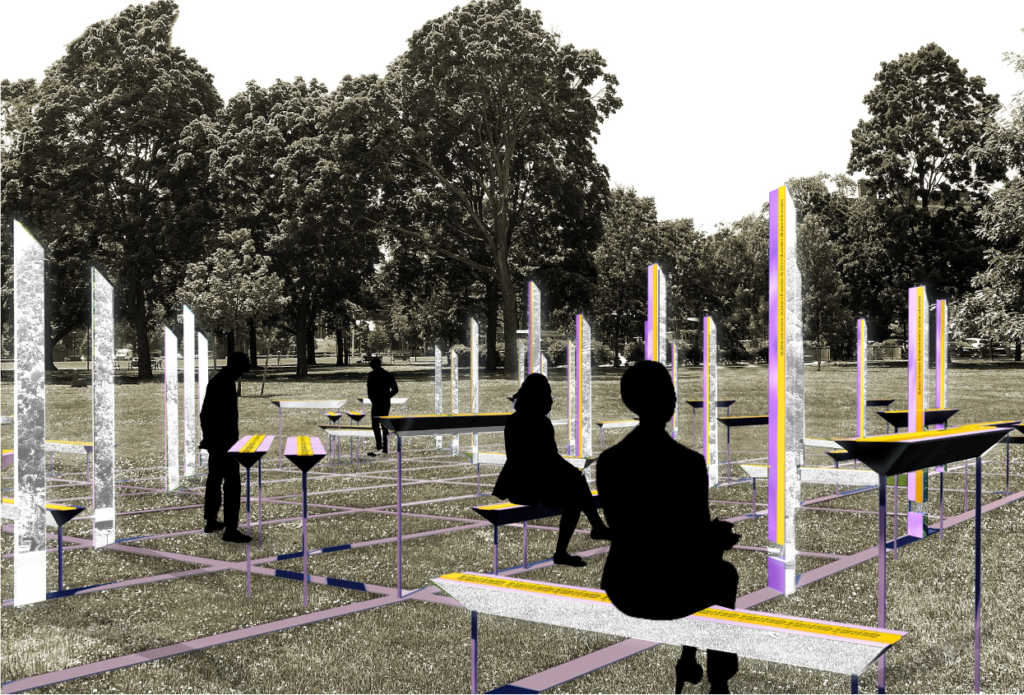

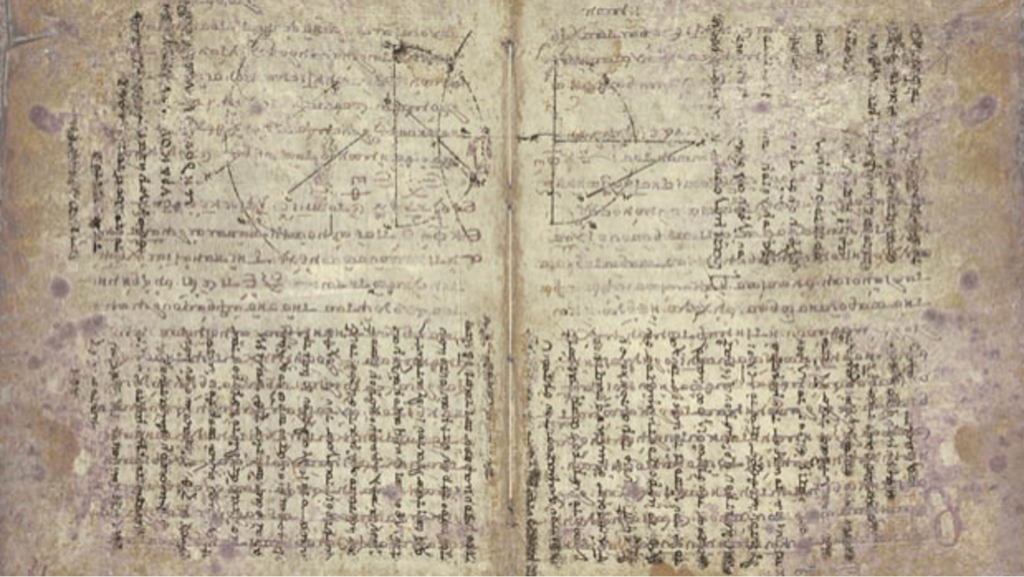

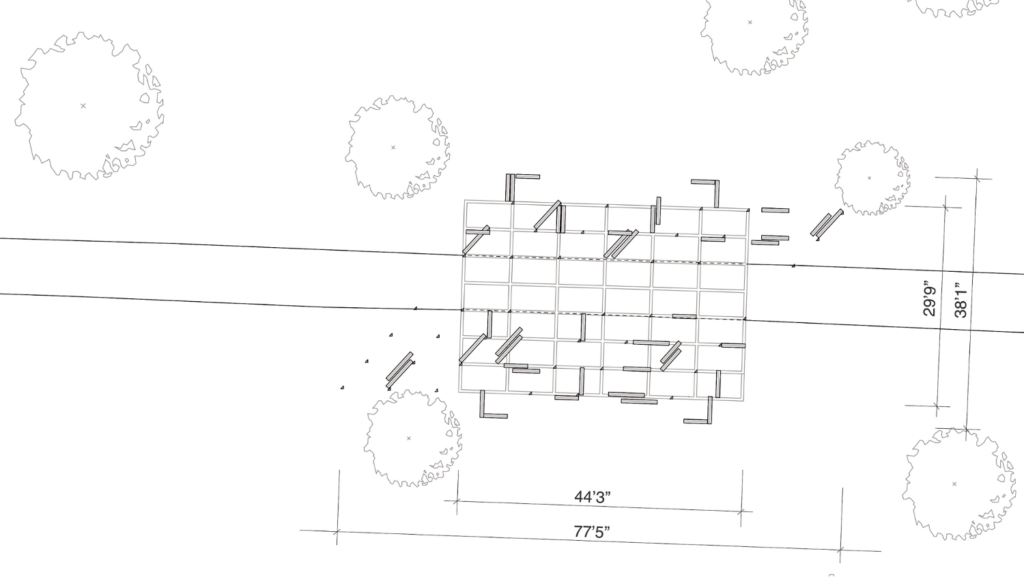

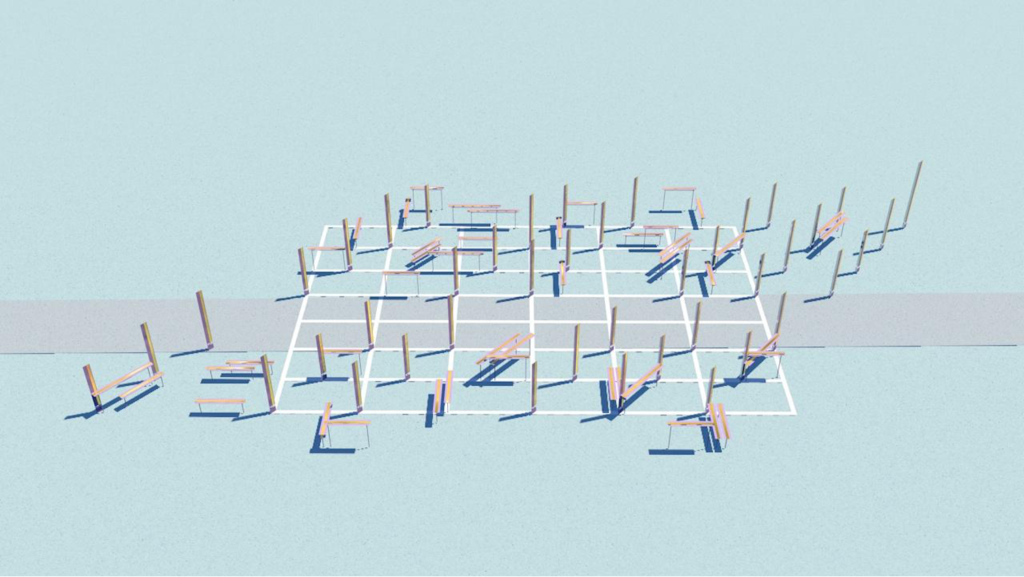

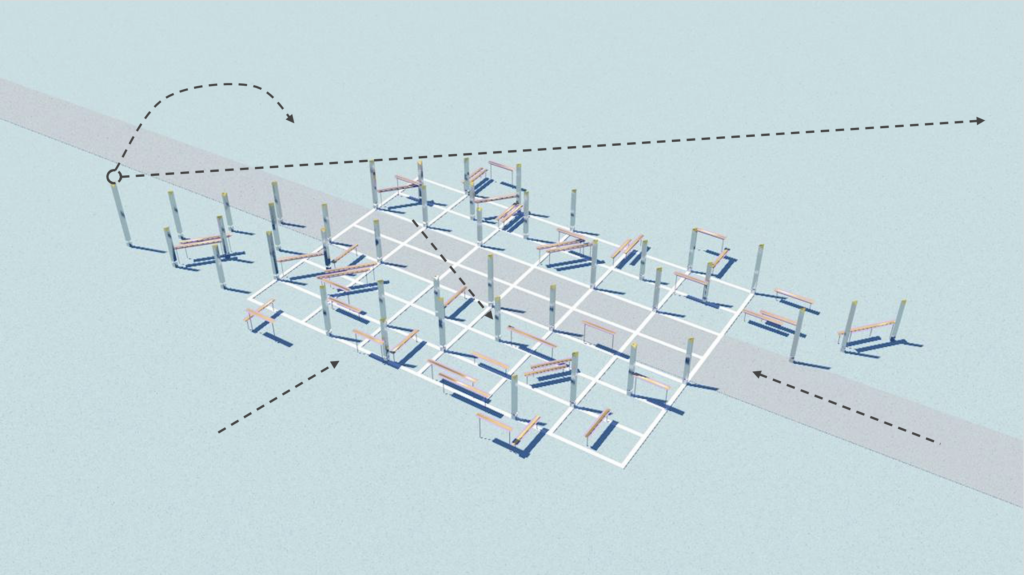

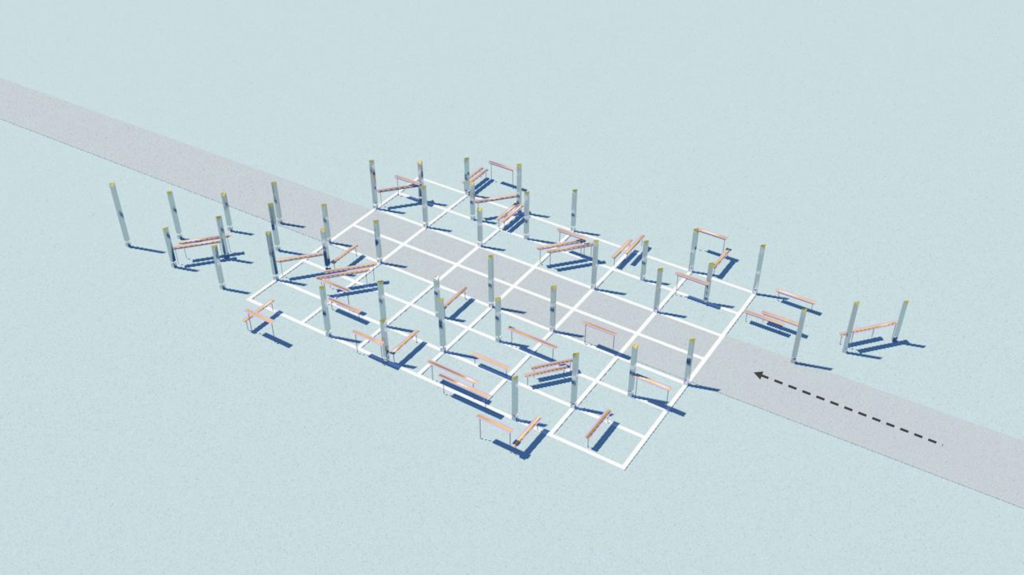

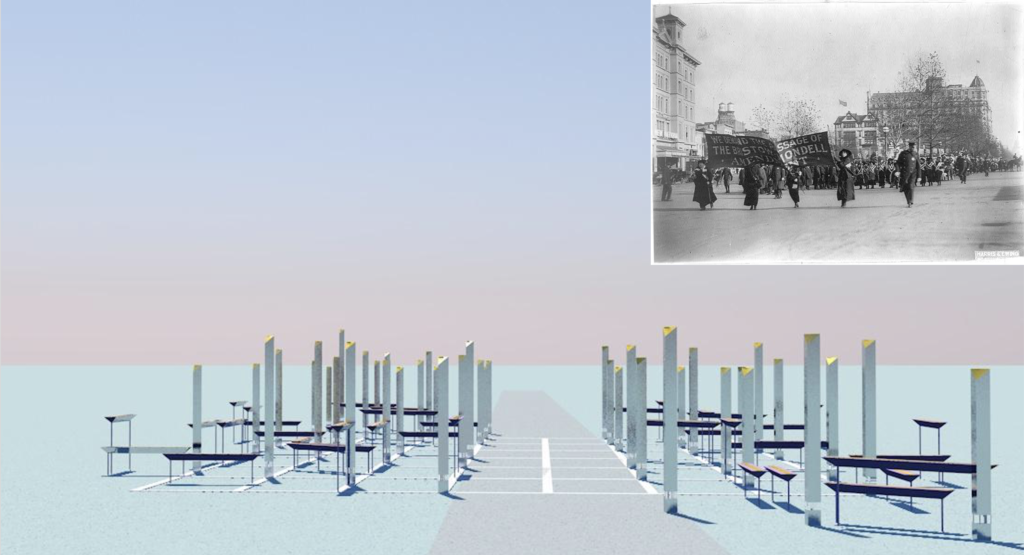

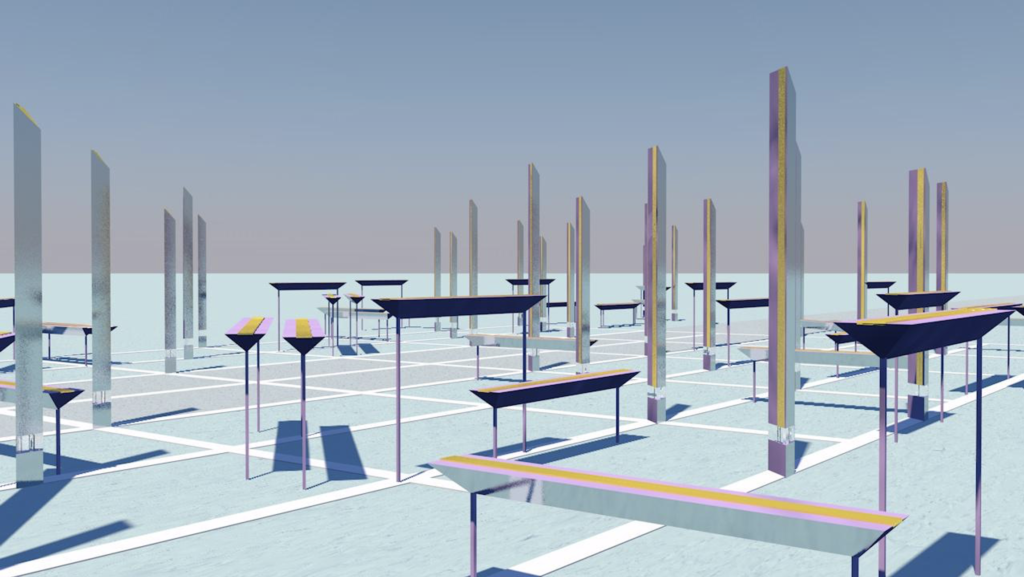

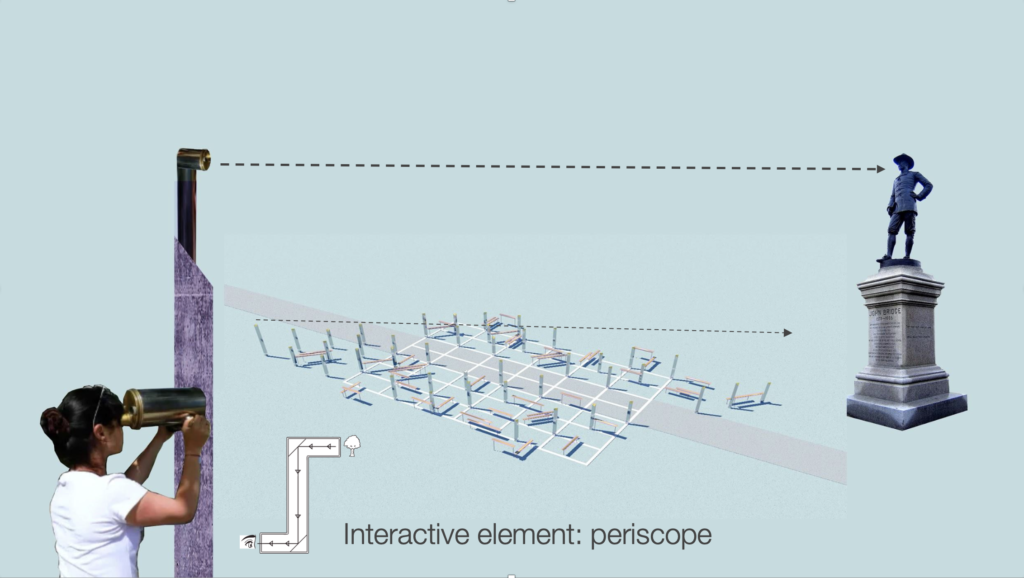

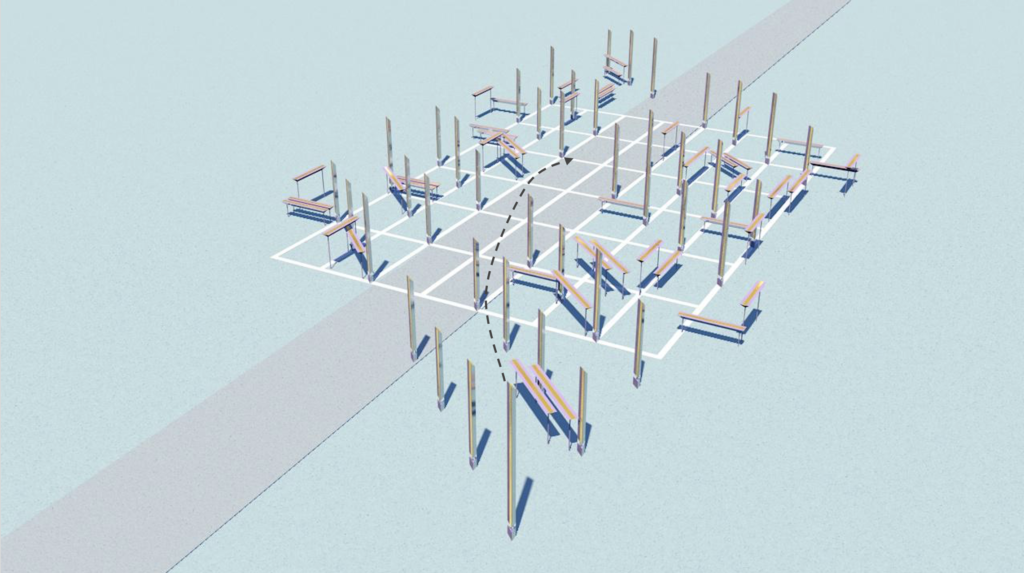

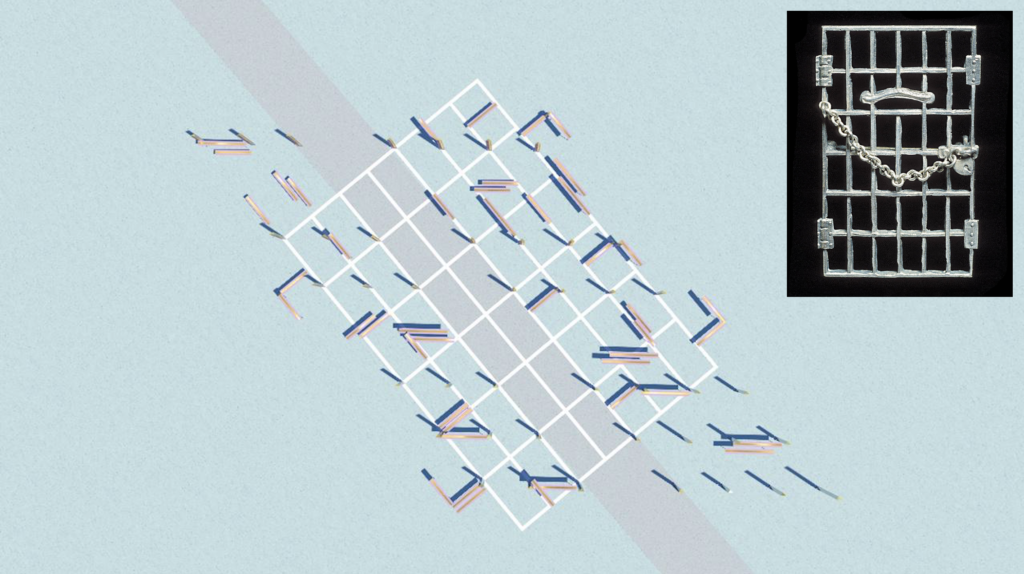

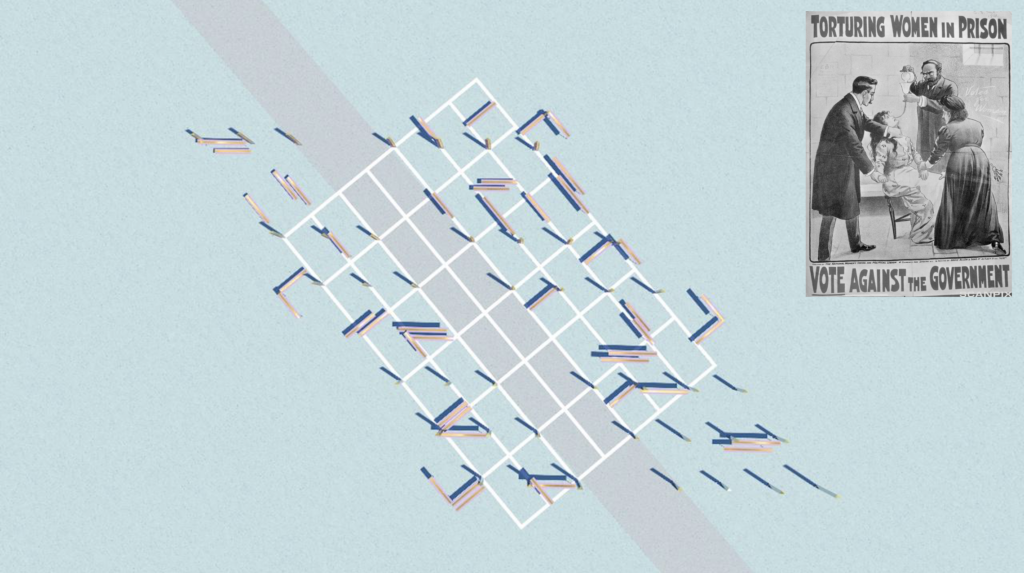

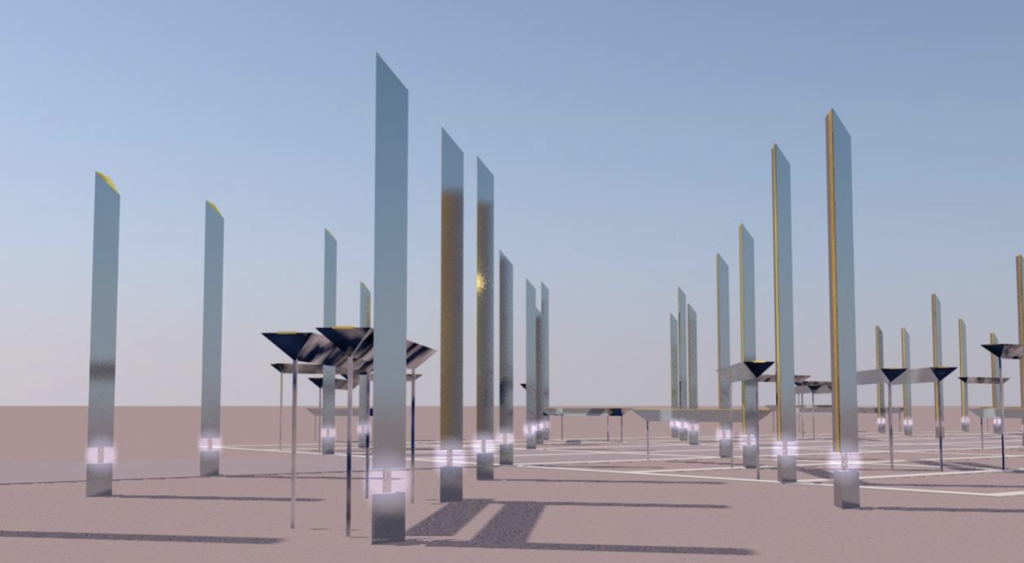

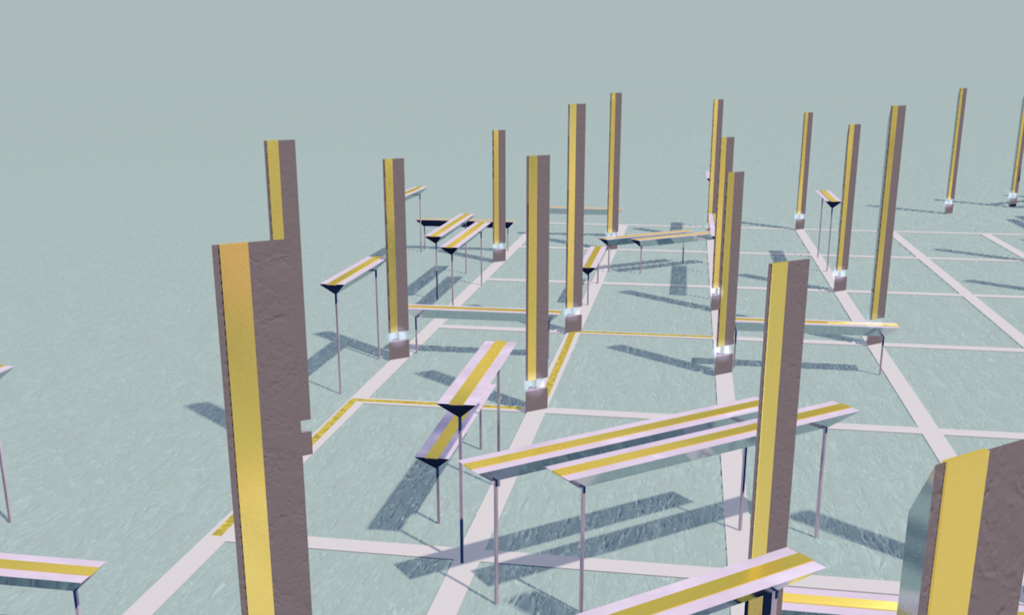

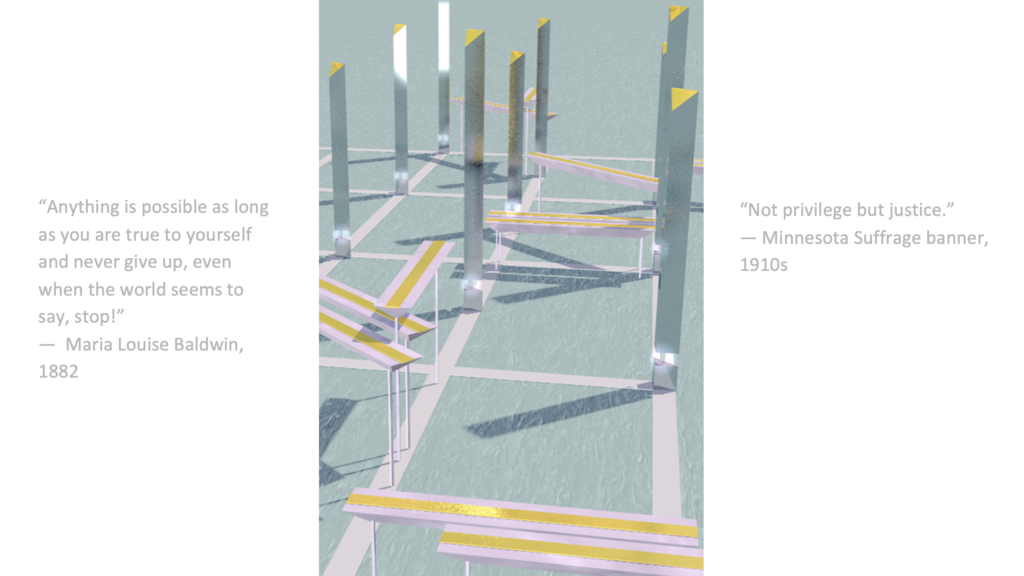

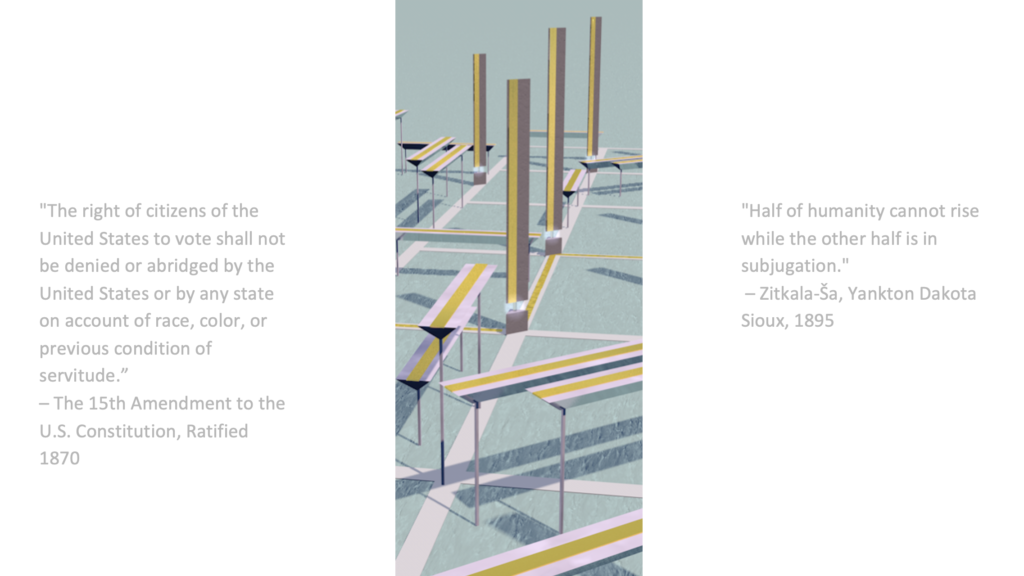

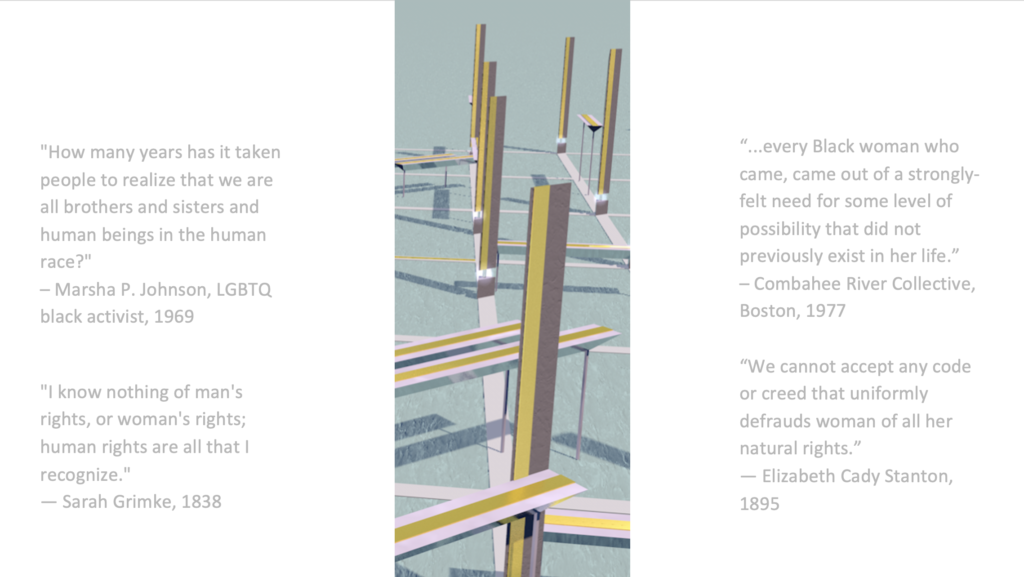

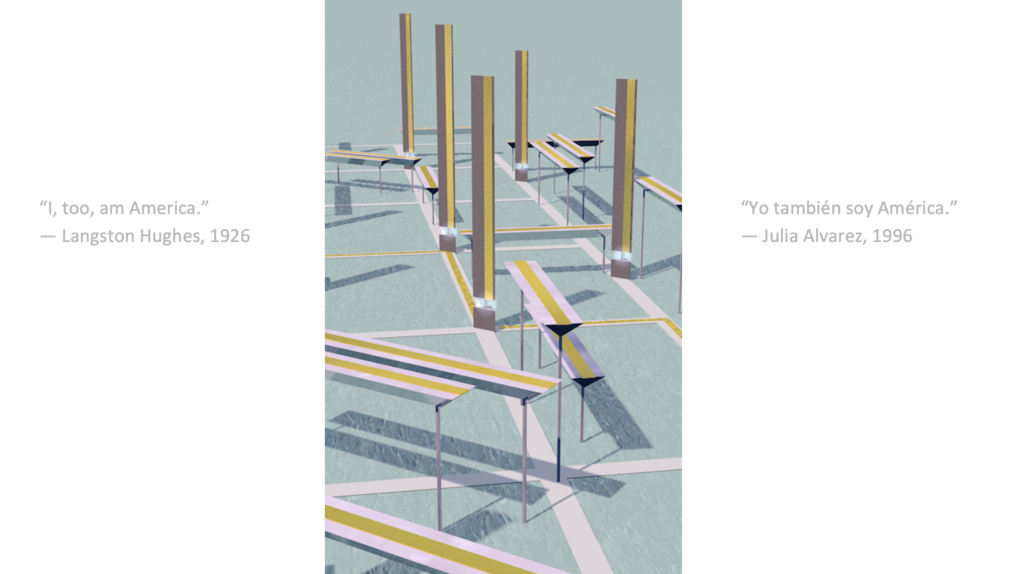

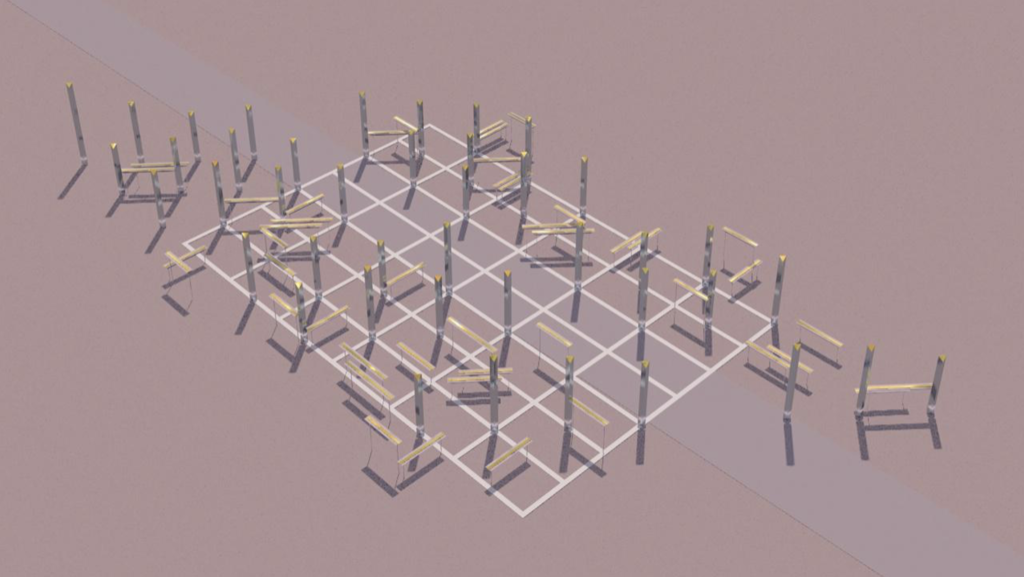

In developing my proposal, I was supported by my research and design development team, including Mariana González Medrano, Jaya Eyzaguirre, Isadora Dannin, and Thera Webb, as well as my husband, Dietmar Offenhuber. My proposed project, titled “Future to Be Rewritten,” envisioned a dignified space for gathering and quiet contemplation about the past, present, and the future of voting rights, social justice, and democracy in the United States. The project name suggests that future history needs to be written and rewritten to include the perspectives of those who have been left out and silenced. This “monument” was to take the form of a three-dimensional palimpsest rendered visible through an arrangement of vertical and horizontal concrete elements. These were to be inscribed with names and quotes from political and feminist activists and thinkers that would have been curated through a participatory process. The cross-written text offered a critical reflection on the subject through a cross-reading of various issues related to voting rights and social justice (see the full project concept below).

The four proposals developed for this site each took very distinct approaches to the subject, and the jury faced a difficult challenge in selecting a project that could address a range of criteria based on the historic and political dimensions of the project and the site, and taking into account the critical public feedback and diverse of viewpoints of Cambridge residents. Some of the challenges facing the jury in their evaluation process involved the question of whether an artwork was successfully addressing the complexities and contradictions of the Suffrage Movement (i.e., figural vs. abstract representation), and the manner in which the contemporary artwork would affect the historic (and protected) site of the Cambridge Common. Following a long process that included public hearings, community engagement, public feedback, and a presentation and discussion with a twenty-person jury, my proposal for the public art commission was finally selected as the winner with an almost unanimous jury decision in September 2020.

Yet, instead of the expected public announcement and a contract for the promised $300,000 commission, I faced a month-long period of waiting for the project to be legally launched by the City. Facing criticism over insufficient inclusion of BIPOC artists in this public art competition, the City was hesitant to proceed with a contract and was looking for a solution (one of the four finalists could be considered an artist of color, but no Black and/or Indigenous artists had been among the finalists).

In the subsequent few weeks, a series of constructive exchanges with the Cambridge Arts Council led to an exploration of various scenarios for how the problems at stake could be addressed. Working from the conceptual and implementation aspect of the project, I was reflecting and thinking about the competition and the various options for how the project could be changed or developed. In my letter to the Director of the Public Art and Exhibitions of Cambridge, I explained:

I realized that regardless of the approach we try to take, we will not be able to get around the core of the problem: that BIPOC artists were not adequately represented in the competition. Any attempt to give them a place now is not going to change that fact.

Since the issue at stake was caused by a flaw in the competition process and not my project – “The Future To Be Rewritten” won because it addressed the issues of marginalized voices extensively – I do not think that the problem can be resolved with artistic means. I came to the conclusion that any new solution to revise my project would neither be fair to the new artists nor to my project.

I believe that a new competition or a direct commission of a BIPOC artist(s) would be the best solution at this point.

As I would not be interested in reentering a new competition, I would like to withdraw my proposal, so that a new solution can be found politically – starting with a clean slate and the revision of the public art commission process. The steps that you and your team have taken to identity BIPOC artists in the public database is already a great move forward.

You and your team have done an amazing job with navigating a complex landscape so far, and I appreciate your professional work and support very much. I am also honored that my proposal was initially chosen, and I am really grateful to you and the City of Cambridge for this opportunity! However, the political situation in the United States is very fragile and it requires all of us to be very sensitive to each other’s concerns and to support the oppressed communities. I would be happy to help you in the future outreach and support of artists from marginalized groups.

At the time of my writing this brief reflection, no new public art competition for this project had been launched, but I was delighted to find out that City of Cambridge is planning to develop their outreach capacities towards advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in its public art commissioning process.

While the pandemic is keeping our community apart, these local and global challenges are putting us to an existential test; as in other periods of violence and injustice, we have to ask ourselves who we are in an especially pressing way. Furthermore, we have to find strength, inspiration, and hope in a moment in which weakness, banality, and despair seem so easy to surrender to. I hope that artists, community activists, and policy makers can work together to take these challenges as opportunities for reinventing the way in which we coexist as citizens.

Credits

Credits: Azra Akšamija (artist concept, project direction). Mariana González Medrano, Jaya Eyzaguirre, Isadora Dannin, Thera Webb (research and design development team). Dietmar Offenhuber (conceptual contributions).

Many thanks to the City of Cambridge for inviting me to be part of this process, and special thanks to my wonderful team, family members, friends, and collaborators who helped me develop this proposal. I look forward to our upcoming discussions.

Project Text: Future to Be Rewritten

The cross-writing links the past, present, and future, by putting them in direct conversation with each other. The viewer sees two (or more) distinct phases at once, which sets them in a meaning-making relation to each other when they otherwise may not be thought of as complementary. It’s about setting up dialogues across history that resist a one-sided and linear reading, which is how the complexities and contradictions of individual events or moments in time can be revealed in a more nuanced way, or at least be open to critical interpretation.

Maya Lin’s memorial utilizes the mirroring effect of the polished black granite and text listing fifty-seven thousand names. This monument became the dominant paradigm of American monument building. Lin’s novel and influential design from 1980 stripped the glory away from battle, recreating the emotional effect of a “sea of graves” in the form of a list. This type of representation allowed her, as art historian Daniel Abramson notes, to invent a “new type of monumental representation of history,” one “without narrativity and moralizing.” 1

Another reference for this project is the Stolpersteine project in Berlin, by Gunter Demnig, which commemorates people who were persecuted by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. This is an ongoing participatory project that represents a form of palimpsests on an urban scale. Citizens are invited to participate, by replacing the existing paving stones of the city with stones that carry brass inscriptions of those who were killed. Stolpersteine literally means “a stumbling stone”, and metaphorically a “stumbling block,” pointing at the need to continuously reflect on what has been erased from history. As citizens are also asked to help take care of these stones among their community, art becomes a tool for safekeeping democracy, peace, and community.

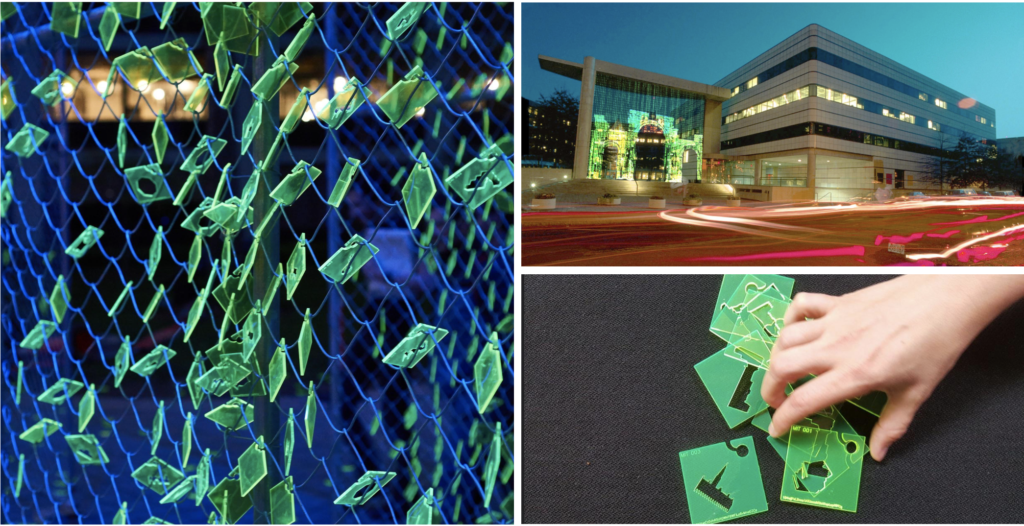

For example, the Memory Matrix project, which depicts fragments of the Palmyra Arch of Triumph and questions the ethics of cultural preservation and humanitarian aid at the time of war. What does it mean to mourn the destruction of Palmyra’s ruins while millions of Syrians are being killed or confined to refugee camps? How does one approach the restoration of purposely destroyed cultural heritage without perpetuating the colonial dynamics? The project was installed on the MIT campus in 2016. The twenty thousand small laser cut pixels were laser cut with holes outlining heritage destroyed during our lifetime. These outlines were created by seven hundred project participants from various locations, who were invited to “empathize” with Syrians by relating the loss of their heritage to the cultural destruction in Syria.

Maria Louise Baldwin, for example, is a significant figure in Cambridge history, she was a celebrated educator, an advocate for women’s rights, and the first Black woman to be appointed school principal in Massachusetts. As the head of the Agassiz School for forty years, her impact on the minds of young Cantabrigian is inarguable. Students at the school campaigned to have the school renamed in honor of Baldwin, and in 2002 the Louis Agassiz School was renamed the Maria L. Baldwin School. Her words still ring true today: “Anything is possible as long as you are true to yourself and never give up, even when the world seems to say, stop!” 2

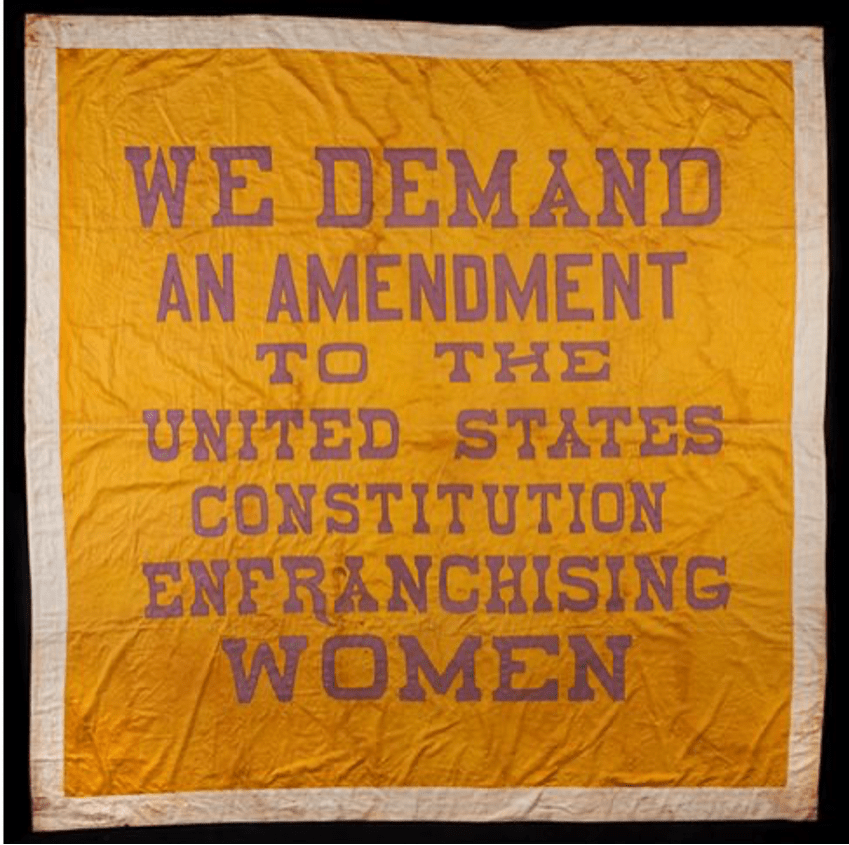

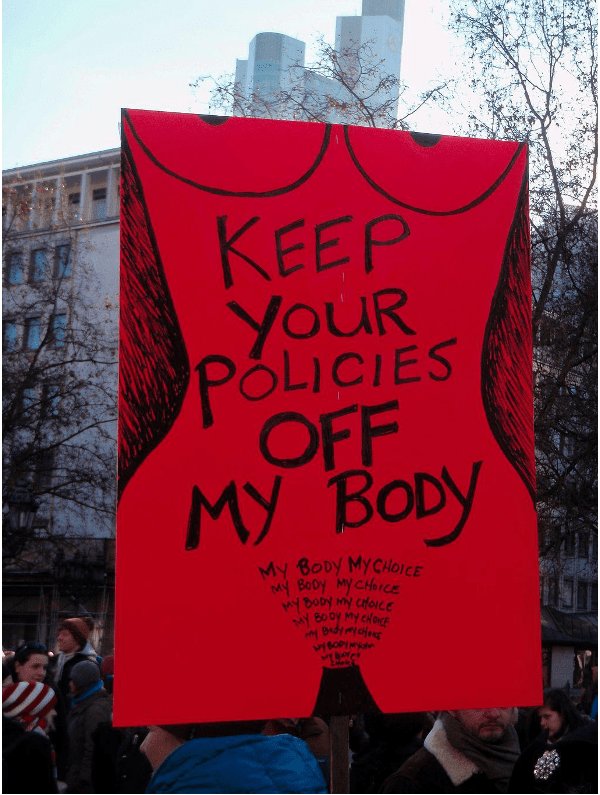

Similarly, slogans from the Suffrage Movement banners from over a century ago, such as the “Not privilege but justice” are nearly identical to the slogans chanted in unison at the today’s Black Lives Matter and Women’s Marches around the world. 3

Banners with suffragist slogans were carried in marches across the country. The intertwining of local Cambridge quotes with banners from around the United States shows the exchange of ideas between suffragists on a local and national level through newsletters, conventions, banners and posters. Both of these quotes remain valid and relevant statements to current issues in women’s rights and social justice.

The Fifteenth Amendment, granting Black men the right to vote, was essentially a moot point for the century following its ratification in 1870. 4 Black Americans, regardless of gender, were effectively disenfranchised through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other means of voter suppression until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

It was not until 1924 that Native Americans were granted citizenship in the United States and thereby the right to vote, regardless of tribal affiliation, through the Indian Citizenship Act.

This quote from female Yankton Dakota Sioux political activist, Zitkála-Šá, cross-read with the Constitutional Amendment, illuminates the complicated history of suffrage for other marginalized groups – it was not only women struggling to advocate for what should have been basic rights for all citizens, and for the validity of their citizenship to be universally acknowledged. 5

The conversations held in these crossed selections include one between Marsha P. Johnson, 6 a transgender woman who was pivotal in the movement for LGBTQ rights, and Sarah Grimke, a vocal suffragist who stopped speaking in public at the request of her husband after years of activism. 7 This pairing highlights the oppression that civil rights activists have been subjected to for over a hundred years.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a major proponent of women’s suffrage was also one of the more outspoken racists in the movement, and she did not support Black women voting. 8 Crossing her quote with a quote from the local Black feminist Combahee River Collective creates a space for viewers to think about the history of racism in the feminist movement. 9

Seventy years later, Dominican-American author Julia Alvarez’s poem “I, Too, Sing America” was written, joining in the conversation with Whitman and Hughes. 11 The repetition of this phrase in both English and Spanish works to emphasize and exemplify the myriad voices omitted in the recording of much of history, be they Black, Latinx, female, or other.

Works Cited:

Abramson, Daniel. “Maya Lin and the 1960s: Monuments, Time Lines, and Minimalism.” Critical Inquiry 22.4 (1996): 679-709.

Alvarez, Julia. “I, Too, Sing America.” Writers on America – Office of International Information Programs, US Department of State. https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/writers/alvarez.htm.

Burgess, Matthew. Enormous Smallness: A Story of E.E. Cummings. New York: Enchanted Lion Books, 2015.

Combahee River Collective. “A Black Feminist Statement.” In Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, edited by Zillah R. Eisenstein. New York: New York Monthly Review Press, 1979.

Const. amend. XV, § 1.U.S.

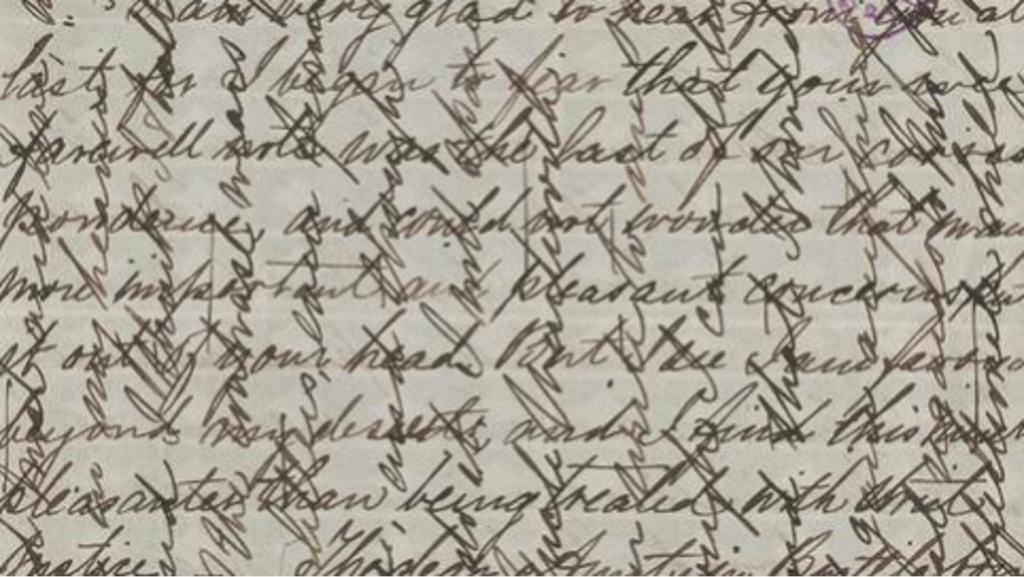

Grimke, Sarah Moore. Letters on the equality of the sexes, and the condition of woman: addressed to Mary S. Parker, president of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute, 1838. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.FIG:002206032.

Hughes, Langston. The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony, and Ellen Carol DuBois, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony. Correspondence, Writings, Speeches. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992.

University of Minnesota’s Women’s Suffrage Club, 1913, photograph. University of Minnesota collection, Minnesota Historical Center Archives. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/largerimage?irn=10322595&catirn=10666856&return.

Zitkála-Šá, American Indian Stories. New York: Modern Library, 2019.

- Daniel Abramson, “Maya Lin and the 1960s: Monuments, Time Lines, and Minimalism,” Critical Inquiry 22.4 (1996): 697.[↑]

- Matthew Burgess, Enormous Smallness: A Story of E.E. Cummings (New York: Enchanted Lion Books, 2015).[↑]

- University of Minnesota’s Women’s Suffrage Club, 1913, photograph, University of Minnesota collection, Minnesota Historical Center Archives, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/largerimage?irn=10322595&catirn=10666856&return.[↑]

- “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Const. amend. XV, § 1.U.S.[↑]

- Zitkála-Šá, American Indian Stories (New York: Modern Library, 2019). “Half of humanity cannot rise while the other half is in subjugation,” Zitkála-Šá, Yankton Dakota Sioux, 1895.[↑]

- US Department of the Interior (@Interior),”‘How many years has it taken people to realize that we are all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race?’ – Marsha P. Johnson, LGBTQ Black activist, 1969.” Twitter, March 31, 2021, 3:09 p.m., https://twitter.com/interior/status/1377261682985172997?lang=en.[↑]

- Sarah Moore Grimke, Letters on the equality of the sexes, and the condition of woman: addressed to Mary S. Parker, president of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute, 1838). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.FIG:002206032. “I know nothing of man’s rights, or woman’s rights; human rights are all that I recognize,” Sarah Grimke, 1838.[↑]

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Ellen Carol DuBois, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Correspondence, Writings, Speeches (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992). “We cannot accept any code or creed that uniformly defrauds woman of all her natural rights,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1895.[↑]

- Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement,” in Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, ed. Zillah R. Eisenstein (New York Monthly Review Press, 1979). “…every Black woman who came, came out of a strongly-felt need for some level of possibility that did not previously exist in her life.” – Combahee River Collective, Boston, 1977.[↑]

- Langston Hughes, The Collected Works of Langston Hughes (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001). “I, too, am America,” Langston Hughes, 1926.[↑]

- Julia Alvarez, “I, Too, Sing America,” Writers on America – Office of International Information Programs, US Department of State, https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/writers/alvarez.htm.[↑]