The World Trade Center tragedy is now considered one of the most photographed events in the history of the world. Most of the photographs were taken by amateurs. Although professional photographers were on the scene immediately, amateur photos and video were picked up by news channels, newspapers, weekly magazines, and by Internet galleries. One of the domestic photo editors at Time Magazine told me she had never seen so many submissions for a single event. She said it wasn’t just bystanders, but also firemen, policemen, and rescue workers who were trying to sell their photographs.

There were many types of pictures that emerged from September 11, the sensational images of the disaster while it was unfolding, the smoldering landscapes of ground zero, nocturnal vigils of mourners holding candles, and solemn pictures of funerals. But of all the pictures, the missing person photos publicly posted throughout New York City stood out as a visual focal point.

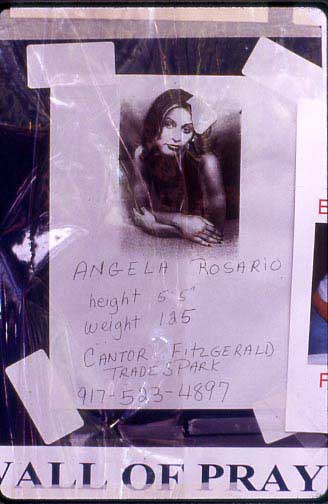

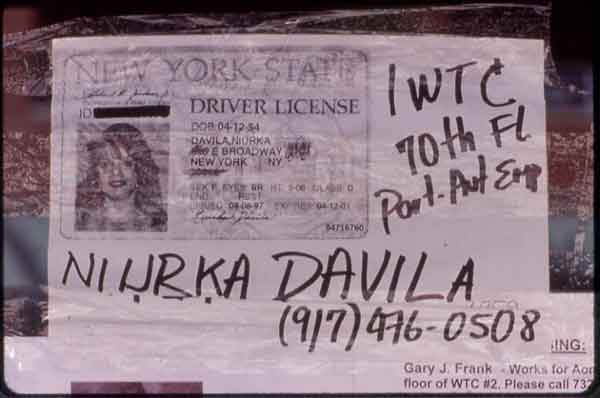

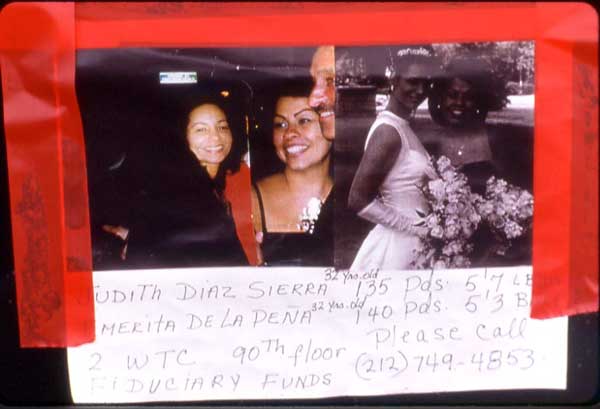

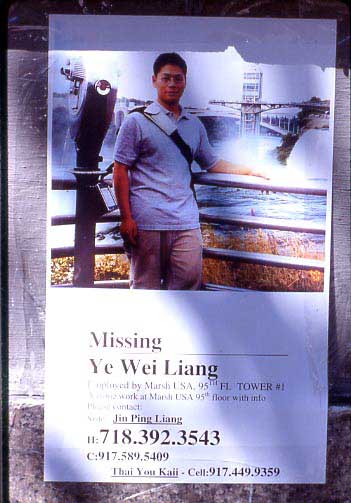

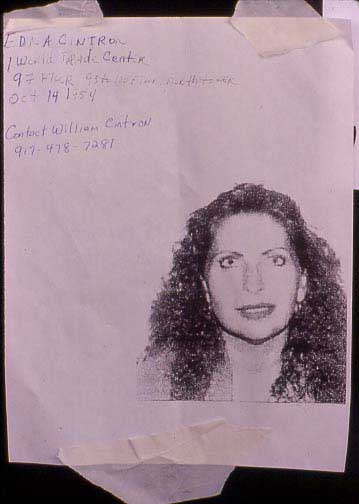

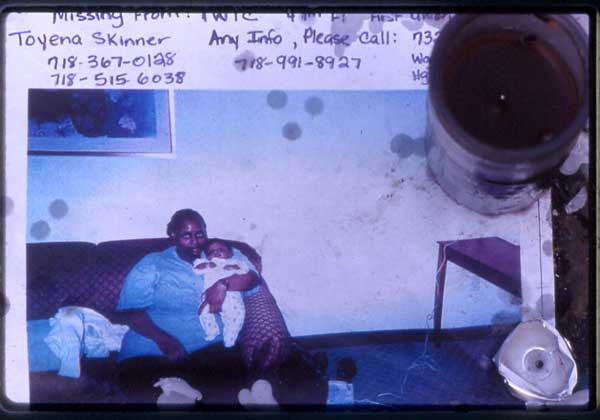

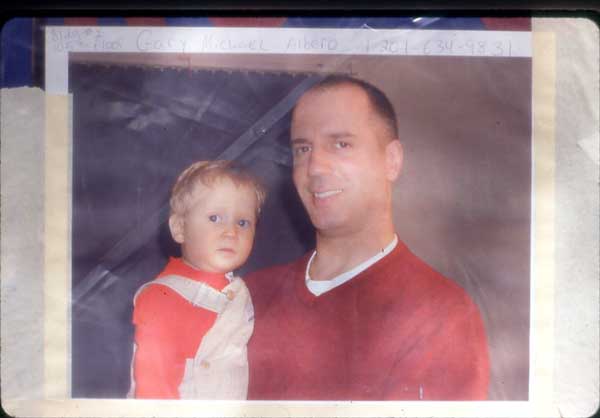

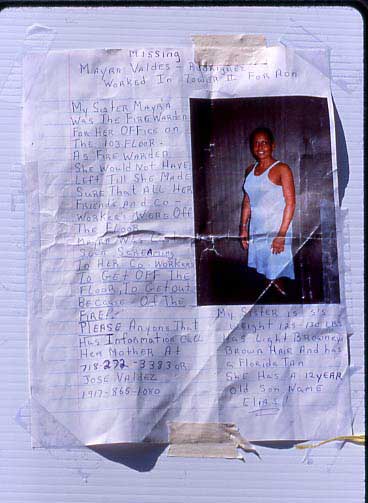

In the immediate wake of the attack, more than 2000 people were rushed to local hospitals. Then there was a chaotic scramble to find everyone. It took take several days for an approximate count to emerge. And when it did, an exaggerated 6,000 missing was the initial number released. At first, there was a desperate hope that they would reappear. In an effort to enlist anyone and everyone in the search, families and friends hastily posted photographs of the missing complete with vital information and distinctive identifiable characteristics to aid recognition. These images were clustered around hospitals, victims’ information centers, public parks, and grieving locations. The first murals were called the Wall of Hope. But as rescue operations transitioned into body recovery, the murals became known as the Wall of Prayers.

As the days progressed, intact bodies were few, and, as body parts began to surface among the ruins, an official request was sent out to the families to gather any personal items such as hairbrushes or toothbrushes which might provide material for DNA matching. The difference between rescue and recovery seemed to mirror the critical distinction between photographs as hope and photographs as prayers. A few days after the attack, one of the chaplains volunteering as a counselor with the families at St. Vincent’s Hospital told me: “There’s the reality at ground zero of body parts and that bodies have been vaporized but there’s also the reality in these people’s heads who refuse to believe that their loved ones are gone. They’re still hoping that they can be rescued or that they’re lying unidentified in some burn unit.”

In that liminal first week, Manhattan was turned into a spontaneous gallery of missing persons. The images were posted on walls, taped to glass partitions at bus stops, wrapped around light posts, stuck on fences, attached to phone booths, plastered onto subway walls, taped to the news vans, placed in front of fire houses, and assembled for the grieving murals. Nothing was planned. Since the first billboards started as acts of desperation, many photos were nothing more than pictures from driver’s licenses and ID cards. Families hastily posted whatever snapshots they could find, even if the picture was out of focus.

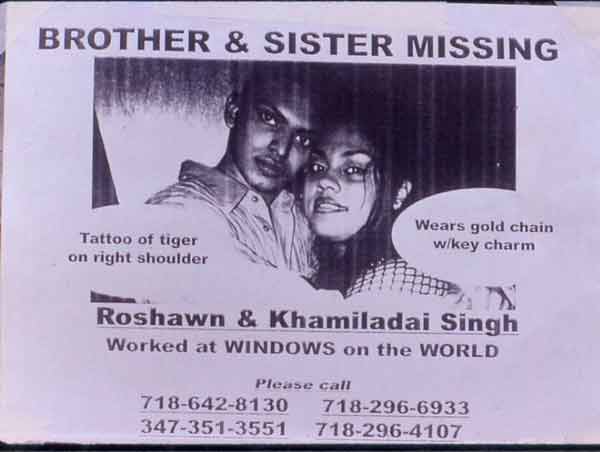

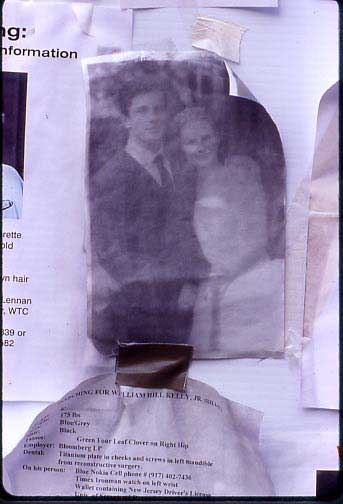

Initially, the writings around the picture listed only the basic biographical information: the person’s name, their company, the floor they worked on, and any unusual markings for identification. These physical details ranged from the obvious to the intimate: accented English (German), wearing dark sport shirt and dark slacks, wears a Cartier Trinity ring on left index finger, has a yellow faced silver Rolex, wears a brown Filipino Rosary around neck, has a mole on the right side of neck, has a birthmark that covers her right thigh, has a tattoo on upper chest of a four leaf clover, has a tattoo on his right arm of the Grim Reaper.

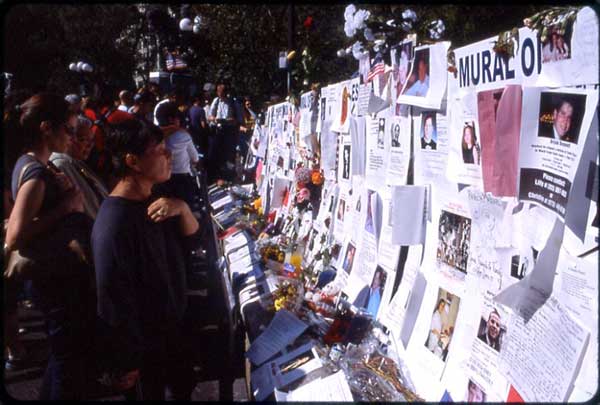

By the weekend, when Mayor Guiliani began to suggest that there was little hope of finding survivors, the photographs began to shift into shrines. Bouquets of flowers were laid underneath the walls and thousands of candles were lit illuminating the pictures at night. The walls were now sacred sites. Families continued to post pictures but the desperate messages for help were changed into visual memorials. Many flyers were now composites of pictures with several different images suggesting the richness of a life beyond mere identification.

As the city began to mourn, Union Square Park at the northern edge of Greenwich Village emerged as the central gathering point. With Lower Manhattan evacuated in the immediate aftermath and everything sealed off at ground zero, people came to the park to look at the lingering smoke in the distance. For many New Yorkers, there was a strong urge to see something in person especially since the televised coverage was quickly shifting from the spectacular inferno footage to analysis and debate. I know I needed to see something more. Though I saw the towers burn and collapse through binoculars from my rooftop in Brooklyn, walked with thousands in a candle light procession to our neighborhood fire house which lost a dozen men, I don’t think the event really hit me until I saw the photographs of the missing at Union Square.

What struck me first about the photographs was the tangible personification of someone who was missing or presumed dead. A common saying in the human rights community is that one murder is a tragedy but thousands of homicides can become mere statistics. Suddenly, I could begin to visualize both the magnitude and the specificity of this tragedy. I was also taken by the diversity. Many commentators made a point of suggesting that the terrorist attack was not just against the United States, but also against humanity. There were over 80 nationalities among the missing.

Because there were several locations with concentrations of the same missing person photos, the pictures were mostly color Xeroxes and black and white photocopies. I was especially moved by the black and white pictures that were so grainy that they resembled fragile drawings. Then there were the flyers that must have been constructed in such a state of panic that words and telephone numbers were crossed out and corrected and faces were penciled over to stress the one person in the photo who was missing. Some people even put up faded newspaper clippings of their wedding pictures to stress that the missing belonged to familial networks. During the first few days, relatives and friends were even wearing the photographs during tearful interviews with the press. One women holding up a photo said to a reporter: “It just makes me feel better to have all these people looking at my brother because he was someone, he had a life, he had a family, he had a story.”

To the local newspapers’ credit, they began to print entire pages of photos and daily profiles of the missing. These brief biographical sketches were also part of the humanization process. With each passing day, we learned a bit more about the missing, such as Deanna Galante, who was among the 628 missing employees at Cantor Fitzgerald. I was haunted by her melancholy picture waxed to a sidewalk at Union Square, and I kept going back to photograph it. Her passions were hairstyling and puzzles and, along with her husband, she was busy redecorating their Staten Island home in anticipation for their first child. Although she was pregnant at the time, her wedding had been in late July onboard a cruise boat to Bermuda. Her husband related that among all their friends and family who went along, she was only one who didn’t get seasick and she danced every night. He also stated that she was at the happiest point of her life, six weeks away from maternity leave. Deanna Galante’s picture and her description was doubly heartbreaking because she was among several cases where families lost more than one person; fathers and sons, twins, both parents, mother and daughter, brothers and sisters.

At Union Square and at other mural locations, the walls of family pictures highlighted our fascination with looking at photographs. In fact, just as the Twin Towers tragedy may be the most photographed incident of all time, the images themselves may also be the most viewed photographs of any single event. Clearly in New York City, there has never been a moment like the aftermath of September 11 when people were transfixed with sadness and wonderment as they studied photographs in a public space. To be sure, there was no one set of meanings for any of the missing person photographs. They were personal and family photographs, evocations of loss, political tokens representing a crisis, forms of resistance, and public image memorials.

Many people noted that the missing person photographs “deepened” their grieving and empathy. I saw several people who must have known the pictured person, reach out to touch and caress the photograph in an emotional parting. The trace of time passed in a photograph has always rendered a certain sense of mortality. But in this case, the pathos of every picture was inexorably related to mass murder. The violence of this separation was defined in the photograph. And yet, the images also reflected a presence which was evoked so concisely by a graffiti message that was spray painted in black paint around New York after the attacks: you are alive. . .

The images also kindled one of the most simple and yet complex human rights questions: why should we care for those with whom we have nothing in common? Given the ethnic and social diversity of New York City, this question is always relevant even in the face of mass violence. Before the attacks, many people in New York might have claimed to have little in common with those who worked in the financial industries. But what the missing person photos brought to the mourning process was a recognition that those who perished came from all walks of life.

The pictures also highlighted the communal meanings inherent to domestic life. People were not awed by these photos, as they were of the dramatic images of skyscrapers collapsing. They could relate because the collection of humble personal pictures evoked a common set of everyday experiences, family gatherings, dinner parties, friendships, holidays and vacations. There was a genuine curiosity as viewers contemplated the face of someone and learned something of their identity. Even with such partial information, the images and the writings stirred a sense of caring not only for the other but also for the intimate circle closest to the self. Many people mentioned to me that the wall made them reflective of their own family snapshots and they wondered if they themselves were missing, which personal photos of theirs would be shown.

Just as the overlap of images blurred the lines between personal and public grieving, the murals evoked a sensation that each missing person was connected to a larger process of mourning. This collective consciousness was in no means incidental. For weeks, many New Yorkers acknowledged a profound change in public life in the city. For a brief window of time, public parks and squares were a fascinating mix of patriotism, spirituality, music, peace rallies, and public grieving. Many of the usual social barriers separating people in New York momentarily came down and people were conversing and connecting publicly with an extraordinary sense of openness. The photos were the center point of this energy, and they helped transform the work of mourning into a call for peace which became the overwhelming sentiment from the Union Square movement.

Unfortunately, the potential to develop this social intimacy into a new kind of public community was stolen as the pictures and the shrines were removed by the Parks Department when the first serious rains arrived on September 21. The Parks Department claimed they were removing the pictures to protect them for historical purposes, and many of the photos and the artifacts have been preserved by museums and folklore societies. But the Park had also become a 24-hour sit-in, and the rains offered an opportunity to evict the sudden homeless encampments and to scrape away layers of candle wax. Without the photos, the spirit of public mourning was gone. Many people I spoke with wanted to grieve longer and were saddened by the “business as usual” discourse perpetuated by the Mayor. And when the media quickly switched their attention to the war machine in Washington, any chance to channel public mourning into debate and introspection was forever deflected.

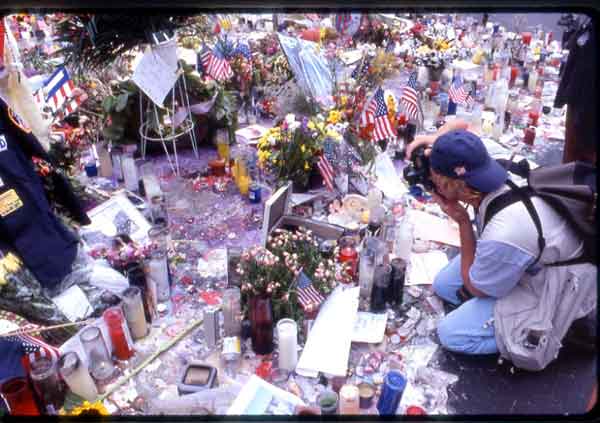

Although many missing person flyers lingered on in various spots for months, there was nothing like the intense concentration of photos at Union Square while it lasted. Unlike the images taken by professional photojournalists which were eventually published in various books, the missing person photos slipped outside of the dominant aesthetic code which dominates media representations. Their plain and unpolished appearance offered an improvisational and vernacular counterpoint to all of the other pictures. People congregated around the missing person pictures because they projected a less mediated relationship with information. During that extraordinary moment after the attacks, it was also the closest they could get to the catastrophe. It was not surprising, therefore, that so many people were photographing the photographs. At every site where missing person photos were clustered, people were photographing the pictures, the candles, the flowers, the cards, the letters, the postcards of the Twin Towers, even the families posting the pictures. A skeptical critic might note that picture-taking limits experience to a search only for the photogenic. This obsession to collect disaster images is not new. Nearly 30 years ago, Susan Sontag in her famous study “On Photography” was one of the first to address the ethics of witnessing with a camera as she lamented that having an experience is almost the same thing as taking a picture of it, and that participating in a public event has become equivalent to looking at it in a photographed form.

I asked several photographers why they were taking pictures of the missing person photos. One man paused, camera in hand, and replied: “It’s the same reason why people slow down when they see a automobile accident. They all stick their heads out the windows for a better look and if everyone had cameras, they would photograph the scene too.” A more pensive answer was: “Well, this is such a watershed moment in American history, even world history, and people want to remember it. I think everyone just wants a memory.” Another person contemplating the photographers told me: “I’d say they were trying to capture some kind of understanding of what went on, to have something tangible to hold onto, to be able to document something which was about invisibility and absence more than anything tangible. Something that was once there, was gone, but what exactly was there? And this is a way of understanding. Or trying to. To capture, through the pieces, the sheer magnitude.”

At Union Square, there was a chance to physically interact with public images that is rare today. Picture taking became an event in and of itself, and everything about September 11 was worth photographing. I was struck by how many people I spoke to at Union Square Park identified themselves as “photographers.” Whether they were amateurs, professionals, or artists, everything there was so charged that experience was bound to stimulate some kind of interpretative action. The Wall of Prayers was also a shrine and photographing was another means of paying respect. A friend said to me: “Two months later, I feel bad that I didn’t take something from Union Square, a candle, a flower, some kind of icon. It was an experience so intense and suddenly it disappeared and now there’s very little trace of this experience.”

Photography after mass violence has always been a crucial form of witnessing. Like many other vernacular photographic murals that have sprung up around the world in recent years to call witness to violence, the Wall of Prayers was another example of how contemporary public memorials tend to be ephemeral and made from visual media. Inevitably, after the all the debates over the reconstruction of ground zero settle into concrete plans, some kind of public memorial will be erected. But I suspect that it will pale against the wall of missing person photos and the collective experience of Union Square. The memorial already happened. It was powerful because it was spontaneously constructed with a raw mixture of love and pain. It was memorable because it was suddenly there and, without warning, it was gone.