This essay begins with a twelve-year old hiss. Some twelve years ago, I was in a UC Berkeley audience listening to Anthropologist Leo Chavez discuss the images of immigration that had appeared on the covers of major news magazines over the previous thirty years. 1 The images he presented were tacky but provocative. Not surprisingly, the covers confirmed that in the popular press the narrative of immigration circulated in an unrelenting celebratory-threat loop: “Isn’t America terrifically welcoming?” bounced to “The nation is under siege!”

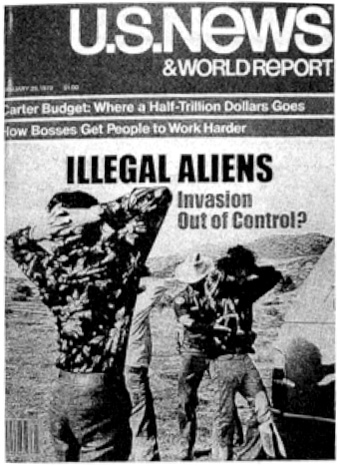

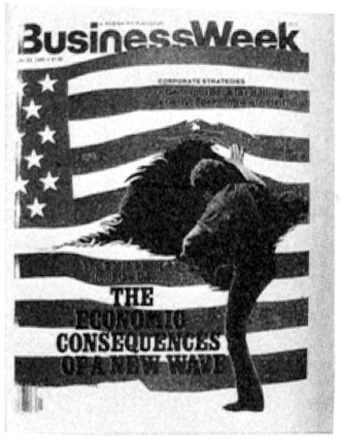

But then, another aspect of those images struck me and I leaned over to a friend and whispered, “This stuff is so homoerotic.” “No it is not.” She hissed back, “It’s a heterosexual rape fantasy.” A bit chastened, I thought, “Of course. Nation as woman. Men as protectors against the penetrative, rapacious impulses of other men.” 2 But, I later wondered, as I reconsidered the images that had struck me: a man climbing through what might be an anus made from the U.S. flag? Police groping or maybe searching men while the image itself draws our attention to the tight butts and crotches of the supposed “aliens.” 3 Did the one interpretation really cancel the other out?

What was not in question for either of us was whether or not sexuality was part of the story. Mexicans have always had a curiously eroticized role in the U.S. popular imaginary. From the 19th century forward, the sex life of Mexicans, or rather white men’s fantasy of it, has subtended expansionist efforts. 4 Certainly, after 1848, a concerted effort to feminize Mexican men in order to hypermasculinize white men and boys found its way into nearly every fictional account that involved Mexico. Over the course of the twentieth century this feminized stereotype gave way in part to that of the drug addled rapist and the domineering, macho cad. 5 “Gay,” however, could not be said to constitute a large percentage of stereotypes proffered about Mexican men in the U.S. press. So I remained puzzled by these insinuations of homoeroticism.

I subsequently tangled with what felt like a half-baked insight and the largely unanswered question: How might a homophobic response to homoerotic portrayals of Mexican men help to structure anti-immigrant hysteria? And could an analysis of anti-immigrant hysteria in concert with homophobia help us understand the ongoing violence in the Southwestern U.S.? It is obviously not enough to assert that these images are simply or merely suggestive of a subtle play with a homoerotics that participates in the grand discourse of othering. Not really interested in the realm of analogy (i.e., othered queers are, like “aliens”, strangers to the normative), I first approached the question by considering the work of the border—analyzing it as an abjection machine and as a state-sponsored aesthetic project, and as a practice, not a static, violent, hybrid place, or a refulgent metaphor but rather as a network of regulatory mechanisms and disciplinary triggers. 6

Significant work on immigration and sexuality has been produced since that confounding hiss. 7 Eithne Luibhéid, for example, offered one of the first monographs to consider how the U.S. uses sexuality to regulate immigration and reproduce sexual categories. Other crucial studies began to unpack the interanimating work of sexuality and citizenship showing, as Jacqui Alexander would insist, that “heterosexuality is at once necessary to the state’s ability to constitute and image itself, while simultaneously marking the site of its own instability.” 8 More recently Alexander has called for further study of the state’s investments in sexuality so that we might understand the “ideological traffic between and among formations that are otherwise positioned as dissimilar.” 9 I hope to take up that challenge in an effort not simply to understand the stakes of heterosexualizing citizenship, but also to see how those stakes are immersed in a nativist homophobia that lays siege to the nation and enables the slow-motion massacre of migrants.

- Leo R. Chavez, Covering Immigration: Popular Images and the Politics of the Nation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.[↑]

- See Between Woman and Nation: Nationalism, Transnational Feminisms and the State. Ed. Norma Alarcón, Caren Kaplan, and Minoo Moallem. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999[↑]

- See, for example, the covers of Business Week, 23 June, 1980 and U.S. News and World Report, 29 January, 1979.[↑]

- Consider, for example, the 19th century U.S. obsession with Mexico’s mixed-race population. See Arnoldo De Leon, They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821-1900. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983. Reginald Horseman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. Martha Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001. Shelley Streeby, American Sensations: Class, Race, and Production of Popular Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.[↑]

- For a helpful summary of this material see Belinda Rincón, “Heroic Boys and Good Neighbors: Militarism, Gender, and State Formation in the Young Adult Fiction of María Cristina Mena.” Unpublished manuscript. Curtis Marez, Drug Wars: The Political Economy of Narcotics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.[↑]

- Mary Pat Brady, “The Fungibility of Borders.” Nepantla (Spring, 2000); Brady, Extinct Lands, Temporal Geographies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.[↑]

- Lionel Cantú, “A Place Called Home: A Queer Political Economy of Mexican Immigrant Men’s Family Experiences.” In Queer Families, Queer Politics: Challenging Culture and the State. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001; Juana María Rodríguez, Queer Latinidades. New York: NYU Press, 2003; Gayatri Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005; Eithne Luibhéid, Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Luibhéid and Cantú, Queer Migrations: Sexuality, U.S. Citizenship, and Border Crossings. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005. Martin Manalanson, Global Divas: Filipino Gay Men in Diaspora. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003; Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.[↑]

- M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.[↑]

- Alexander, 190.[↑]