A response to the presentations “Queer Pedagogies in Public Places” by Jennifer Miller and “Tilting Pedagogies as Utopian Intervention – Outrage, Desire, and the Body in the Classroom” by Marisa Belausteguigoitia Rius at the The Scholar & Feminist Conference 2013: “Utopia.” Watch the videos here:

The Scholar and Feminist Utopia conference began with a seed of an idea: around the world, people were claiming hope in the face of violence, and it seemed increasingly probable that the most outrageous, seemingly impossible ideas just might be our way out of overarching systems of oppression; The wager of the conference was that some of these ideas and the hope they inspire would come at the intersection of activism, academia, and art. Perhaps nowhere is this hope and the change in power structures that it portends more needed than in education, the site of the reproduction of knowledge. At “Utopia,” artist/scholar/activists Jennifer Miller and Marisa Rius brought us a compelling vision for feminist and queer approaches to education. Their strategies for crafting feminist pedagogies can be implemented anywhere—they span the classroom, the park, the prison, and even, I would argue, the computer screen. Drawing on decades of theory and practice, these instructions offer us a blueprint for education at its best.

Consider the (Bearded / Tilted) Body

One of the primary interventions of feminist and queer theories has been the recognition of diverse life experiences and methodologies as legitimate and critical in shaping our approaches to the world and each other. At the beginning of her talk, Miller riffs that her “collaboration” with Rius will take the form of a Cage/Cunningham “Happening”—leaving up to chance the meaning of their pairing. This analogy provides a suggestive lens for both scholars’ analyses of educational practice. The famous “Happenings”—performances that relied upon what happened in the moment given certain conditions—were powerful because of the spontaneous and unpredictable nature of events. Each event, ultimately, was utterly dependent on what the individuals present brought into the situation, and how their experiences mingled together. There can be no repetition of a Happening because the elements are never the same. In the context of education, this approach suggests that there can be no standardized version of education.

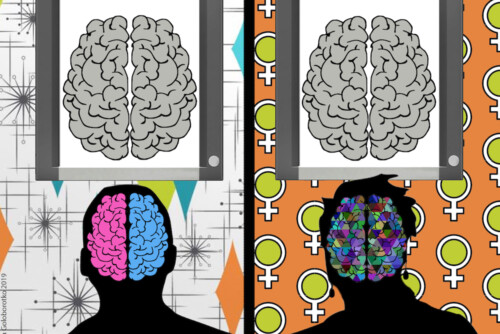

In particular, for Miller and Rius, the primary element determining the contours of educational experience—one that is frequently missing in consideration of pedagogy—is the body. Our bodies mediate our experience of the world. Yet as both Miller and Rius articulate, education, especially in the classroom, tends to ignore bodily realities as much as possible. Of course, in practice this means that those in power develop educational materials designed for bodies that fit a (racist/sexist/classist/ableist) “norm” which is in fact not normal at all.

When confronted with a body that refuses to be made invisible within the dominant educational paradigm, traditional education finds itself disrupted. Rius describes Dani, a child whose frequent dancing has brought about the wrath of her teachers, who argue that she is deviant and inappropriate. Dani’s dancing, tilting child’s body, as described by Rius, upends the foundations on which the course—which imagines itself as bodiless, body agnostic, body neutral—rests, and causes the instructors to insist that their teaching cannot proceed under such conditions. Miller similarly invokes the ways in which the supposedly aberrant body can shake up the classroom. Regarding her beard, she shrugs and says offhandedly, “it grows there.” Yet, to have the bearded lady “as ringleader, not sideshow” inherently upsets historically dominant models of knowledge production and entertainment. By not only acknowledging bodily difference but actively following it through to its conclusions, the range of possibility is radically expanded and altered. This has been shown repeatedly in the medical and scientific sphere of late, as we recognize how much of our assumed understanding of the human body rests upon the exploitation of bodies deemed “abnormal,” and the concurrent focus on a certain, limited, set of bodies as representing an imagined whole. Centering bodily experience when drafting educational practice similarly opens up a wide variety of questions and options: How does the imagination of a normal body lead to practices that materially fail to educate most students? And, what new possibilities for educational practice become available when we take the dynamism and diversity of bodies and bodily practices into account?

Making visible the bodies of those deemed outside the norm, and in so doing shifting assumptions of knowledge production, remains a difficult and contested process. Miller tells us Circus Amok will “speak to people who are not choosing to see us,” as a central tenet of pedagogy. At BCRW, we frequently have the joyful experience of being physically present with one another. We are able to bring together the embodied selves of academics, artists, and activists who in speaking and listening to one another, in eating together and sitting together, bring about shared knowledge and disseminate learning. At the Utopia conference, we were delighted to hear people extrapolating on talks and workshops during snack and coffee breaks, building out ideas and resonances at a reception.

Yet we also try to encourage and incorporate connections outside of the physically present. “No tweeting!” Miller instructed firmly at the beginning of her talk—she asks us “to see each other be present in the room.” But Twitter and other digital media platforms are often spaces where we can extend our bodies, our ability to be present with each other, our chances to “speak to people who are not choosing to see us.” Similarly, Rius points to the ways citational practices can make some people appear, while erasing the visibility of others. As we release our event videos across networks both embodied and virtual—from fingers typing to eyes watching and ears listening—we must continue to seek methods that engage our bodily experiences and the identities we bring to bear. Considering the body becomes all the more important as we increasingly do not share bodily space together.

Friction and Connection

The thing about bodies is that they are both ever present, well known, and often framed as the site of the most foreign encounters. Miller and Rius ask us to consider what bodies we expect to educate. Miller controversially states that she outs all her students, making everyone queer, in order to shift the kind of educational paradigm they walk into, while Rius advocates the tilting, whirling body, unsettled, leaning, in motion, over the silent and still automaton that schools may press students to become. They argue, in these examples, for displacement as a means of education. Yet there is also a call for education that can draw people in by appealing to the familiar, the comfortable, the known. Miller describes how Circus Amok “speaks easily to all kinds of people,” or “clearly and easily to all” as Rius echoes.

In the spring, BCRW was honored to host author, editor, and activist Janet Mock in a salon honoring her memoir, Redefining Realness. So many people articulated how viscerally Mock’s book affected them, with most highlighting recognition as a primary force—that seeing “someone like me” in her book struck a deep chord. Such a bodily experience of identification can open all kinds of pathways to learning—through the articulation of experience, context emerges that latches on to points of “oh, yes, that happened to me,” pushing for a deeper and more expansive view of the world. Educator, artist, and scholar Amalia Mesa-Bains argues in Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism that the goal of education “is to apply knowledge to develop meaning—relevant and useful education that engages the learner.” 1 Learning has to connect to student lives—be familiar, and thus relevant.

But as Miller later suggests, not everyone immediately connects with what is being taught. Dislocation remains a critical component of teaching. Miller describes the chant and dance Circus Amok teaches about what to do if stopped by the police. Those who do not regularly experience stop and frisk policies have to take the step-by-step advice into their bodies, learn what to do. And as she argues, those who do frequently experience these violations are often being exposed anew to “queer survival strategies,” embodied in the movements that assist in memorizing the song: “Stay cool, stay calm, you have the right to remain silent/Don’t run, don’t resist, and get that badge number.”

The legacy of feminist and queer theories here emerges again—to make strange the familiar, and make familiar the strange. It is OK if educational material is hard sometimes, inaccessible at first—it may need to be digested, changed, shifted before it can be recognized. And it is excellent if such material resonates instantly—this can allow for new growth and connections through proximity and analogy. Rius and Miller pull us towards such “slanted scenarios,” as Rius calls these learning environments, enjoining us to perform an “operation that favors friction”—sometimes, at least, while other times the smooth ride takes us somewhere further afield. The presence of such duality is encapsulated by returning to Rius’s tilting—something tilted is almost familiar, but not quite, and can even be so distorted by whirling and movement as to be completely opaque. This is what we should strive for—glimpses of understanding amdist the rollercoaster exhilaration of confusion brought about by moving one’s body and one’s mind.

- bell hooks and Amalia Mesa-Bains, Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2006), 46.[↑]