The Silhouette Artist and the Shadow Dancer

Baker’s unpredictable, Topsy-like comedic moves lead us to an unlikely yet highly provocative twenty-first-century trickster and comic artist, one who also embraces the pickaninny figure as one of her muses. This artist is Kara Walker.

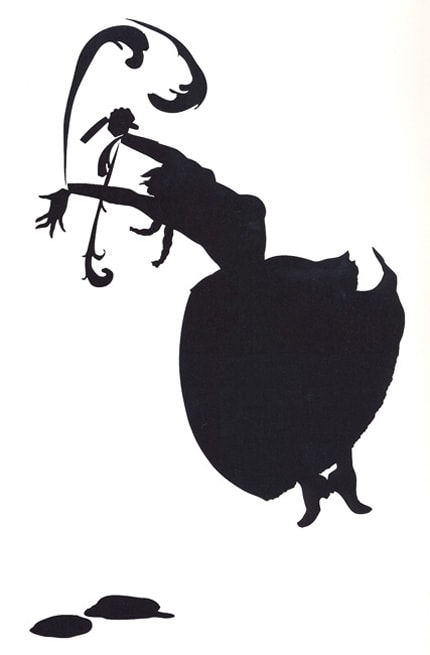

Critic Annette Dixon suggests that we consider the comedic elements of Walker’s controversial art. Walker’s humor, she argues, “is slapstick and debasing (evoking that of the minstrel show), yet without it, the horrific aspects of the scenes would be unbearable.” 1 But we might stop to ask what it is about the space that the silhouette creates that enables humor. Humor is allowed to ferment and thrive in these darkened spaces. What makes this possible is that although the silhouette is historically “tied to the conventions of caricature,” Walker has managed to utilize this form in order to “engage the question of how one represents race through reduced means. It is through outline and shape, and the intervals between shapes, that information is conveyed,” explains Dixon. 2

Walker lobs ribald and pornographic punch lines through the exaggerated, grotesque shapes of her forms. Often in profile, her minstrel figures break out of their straitjacketed shapes in bursts of startling historical and political malapropisms. Beyond the disobedience of their pickaninny figurations, though, Walker and Baker have even more in common if we consider Baker’s performance in Zou Zou and her use of the mobile silhouette—the playful shadow puppets [video] that she deploys at the end of the film as Zou Zou literally tries her hand at a career on the stage.

In Zou Zou, Baker’s shadow puppet performance operates as the critical turning point in the plot. It provides a bridge between Zou Zou’s role as a laboring laundress and her point of entry to the stage and subsequent stardom. But perhaps even more suggestively, this climactic scene in the film demonstrates and celebrates Baker’s deft use of her hands. Invoking a whimsical gesture associated with child’s play and innocence, Baker nonetheless reaffirms her sophistication as a professional comic performer in this mischievous scene. Through the savvy work of her hands, she conveys her phantasmagoric gifts at making shapes in shadowed profile and exploits the darkness of her own shadow. Oscillating, bobbing, and weaving inward and outward in the creation of multiple and unexpected shapes and images, Baker here defies the visual reification (and calcification) of her own body. Here the hands of the shadow puppeteer shift our attention away from the overdetermined, sexualized body parts of Baker and black womanhood and toward the virtuosic hands that make both recognizable and nonsensical shapes that transmogrify and transfigure in the space of the shadow. And it is Josephine Baker’s ability to utilize the nonsensical in her performances that finally reinforces her alluring comedic gifts.