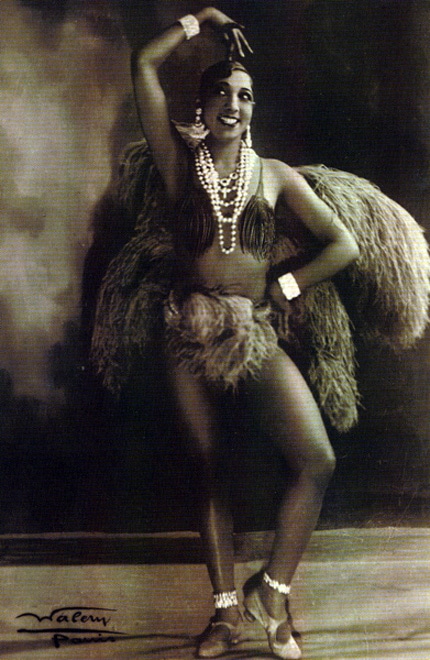

While I’ll return in a moment to the topic of those perpetually crossed eyes, I want to think a bit more about Baker’s mischief at the end of the line.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Karen Dalton remind us, for instance, that Baker’s moves were both dazzling and disorienting. They point out that in her breakthrough role as a chorus line girl in Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along, “audiences were bowled over by her frenetic dancing and outrageous clowning, the visual equivalents of malapropisms” (910). What, we might ask, does it mean to do the “wrong” dance at the right time? What are the consequences of making incongruous gestures within certain contexts?

Such questions should remind us of the points that Margo Jefferson raises about how one of Josephine Baker’s gifts was her ability to navigate incongruities, to take “contradictory dances and make them one or even show them operating at the same time.” By mixing American musical theater with blues and jazz phrasings and French music hall aesthetics, Baker was able to create dissonant humor. This dissonance, one might argue, emerged out of that end space. 1

Josephine Baker’s end of the line is not just spatial, but temporal as well. We should recall that Baker’s own Topsy incarnation in the 1924 musical The Chocolate Dandies, Topsy Anna, showcased her in full “blackface, wearing bright cotton smocks and clown shoes” and provided her with the platform from which to distort time with her lightning movements. The poet e.e. cummings, sounding like Charles Dickens watching the African dancer Juba, would revel in the racist spectacle of this “‘tall, vital, incomparably fluid nightmare which crossed its eyes and warped its limbs in a purely unearthly manner.” (Dalton and Gates, 911)

While cummings was representative of white spectators who fetishized what they perceived as physical deviance in Baker’s dance style, Baker’s choreography actually amounted to intelligent and inspired aesthetic design. Anthea Kraut argues that “Baker inevitably seemed to forget the steps she had been taught” but would wind up “performing her own idiosyncratic moves in their place.” 2 We might think of this gesture as a kind of choreographic interpellation. By this I mean that Josephine Baker inserted a kind of dance into a space where it was not expected.

- Margo Jefferson, interview, “Josephine Baker: The Woman,” DVD extra, Zou Zou (King Video, 2005). Margo Jefferson, interview, DVD extra, Princess Tam Tam (Kino Video, 2005).[↑]

- Anthea Kraut, “Between Primitivism and Diaspora: The Dance Performances of Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Katherine Dunham,” Theater Journal 55 (2003): 438.[↑]