The End of the Line

We know from Jayna Brown’s brilliant forthcoming study of early twentieth-century black female performance culture that Baker was one of many working black female entertainers at the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance who experimented with counter-hegemonic forms of modern dance that generated “satirical comment on the absurdity” of “spurious racialisms.” 1

By Brown’s account, these female pioneers of black dance—women like Ida Forsyne, Ethel Williams, Baker, and many others—actively transformed canonic blackface roles through their own innovative movements on the stage. In the hands of these women, iconic minstrel caricatures—from nameless “pickaninnies” to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Topsy—transmogrified into tools of farce that had the power to “disrobe authority” (7). As Brown has persuasively argued, “Topsy has a keen sense of time, as her body has been marked by the uses to which her body, and the bodies of other slave children, was put. Topsy has no investment in keeping the ‘master’s time.’ She contorts and bends it—syncopates it, rags it, swings it…. She creates play zones out of its distortion. Pushing at boundaries of time’s rhythmic containing, the dancing slave takes time out of its routines, its disciplinary actions on her body” (Chap 2, 41).

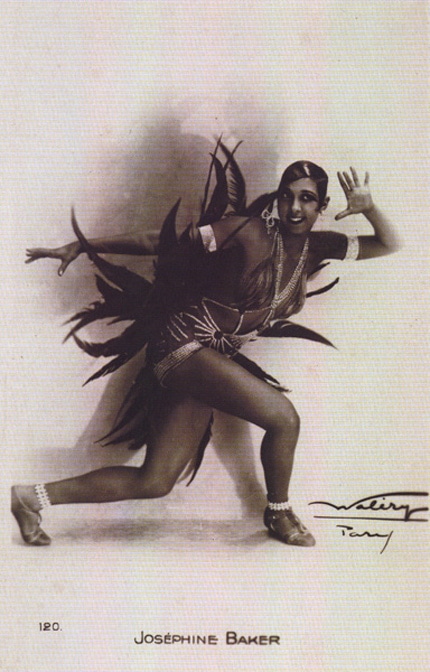

Baker got her start in theater by performing these Topsy-like, black vaudeville minstrelsy roles, but she came to stardom extending the innovations of Ethel Williams, as several cultural critics have duly noted. It was Williams who first stylized the routine that became known as the “mischievous girl at the end of the [chorus] line,” and Baker would later follow suit. As Brown reminds us, Williams “refused to toe the line.” And as Williams puts it, “‘I would be doing anything but that. I’d do the ‘ball the jack’ on the end of the line every kind of way you could think about it. When the curtain came down, even my fingers were doing ball the jack outside [the curtain]'” (Chap 2, Chap 5, 10).

Baker would later gain great notice for following Williams’s moves. As one contemporary reviewer remarked of Baker’s performances, “she was the little girl on the end. You couldn’t forget her once you’d noticed her, and you couldn’t escape noticing her. She was beautiful but it was never her beauty that attracted your eyes. In those days her brown body was disguised by an ordinary chorus costume. She had a trick of letting her knees fold under her, eccentric wise. And her eyes, just at the crucial moment when the music reached the climactic ‘he’s just wild about, cannot live without, he’s just wild about me’ [from “I’m Just Wild About Harry”], her eyes crossed.” 2

- Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Race Mimicry, Black Chorus Line Dancers & the Modern Body (Durham, NC: Duke UP, forthcoming), 7. All future references to this text will be made parenthetically unless otherwise noted.[↑]

- Karen C.C. Dalton and Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Josephine Baker and Paul Colin: African American Dance Seen Through Parisian Eyes,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Summer 1998): 910.[↑]