“Relajo wants everyone to be an actor”: killjoy pleasures in the 1970s

The first public demonstration of gay and lesbian activism in Mexico took place on July 26, 1978, in Mexico City, when the Frente Homosexual de Acción Revolucionaria (FHAR) organized a contingent of twenty to thirty people to join the march in support of the Cuban revolution (marking its twenty-fifth anniversary) and the tenth anniversary of the beginning of Mexico’s student movement. They printed up a flyer introducing themselves as “conscious homosexuals [who] decided to come into the street in this march with all of the country’s oppressed, even knowing that anti-homosexual attitudes are not the privilege of the ruling class.” 1 This rather cleverly phrased critique of left-homophobia aside, there was nothing about their participation in this march, or their declaration of principles, that could be understood as contagiously funny, and so might seem an odd example of queer relajo. But if we turn to Portilla’s analysis, we learn that laughter is the most common but not the only effect of relajo.

Indeed, in Portilla’s discussion of “the fiesta,” whose primary value is the communication of “joy,” the relajiento (the person mired in or “full of relajo” 2 ) can also be “an aguafiestas, a killjoy.” 3 Portilla explains “that relajo is possible only when value appears embodied in a repository or agent that can be a person, an institution, or a situation, and at the same time, the value calls on my support in order for it to acquire full reality.” 4 Whether in its killjoy or all-joy form, relajo interrupts the collective affective investment necessary to sustain the value embodied by a person, institution, situation, or in this case, social movement. Of course, in its killjoy form, relajo resonates with Sara Ahmed’s “affect aliens” – “feminist killjoys” and their kin, the “unhappy queers,” “melancholic migrants” and “angry black woman… [who] may kill even feminist joy, for example, by pointing out forms of racism within feminist politics” – who “might kill joy simply by not finding the objects that promise happiness to be quite so promising.” 5 But by describing an act and experience that can be as much, or primarily, about illicit joy as killing joy, relajo helps us to recognize and articulate a peculiarly inviting, exuberantly critical, irreverent and generous mode of activism that helps to incohere – scramble and queer – power at the faintest signs of its coherence.

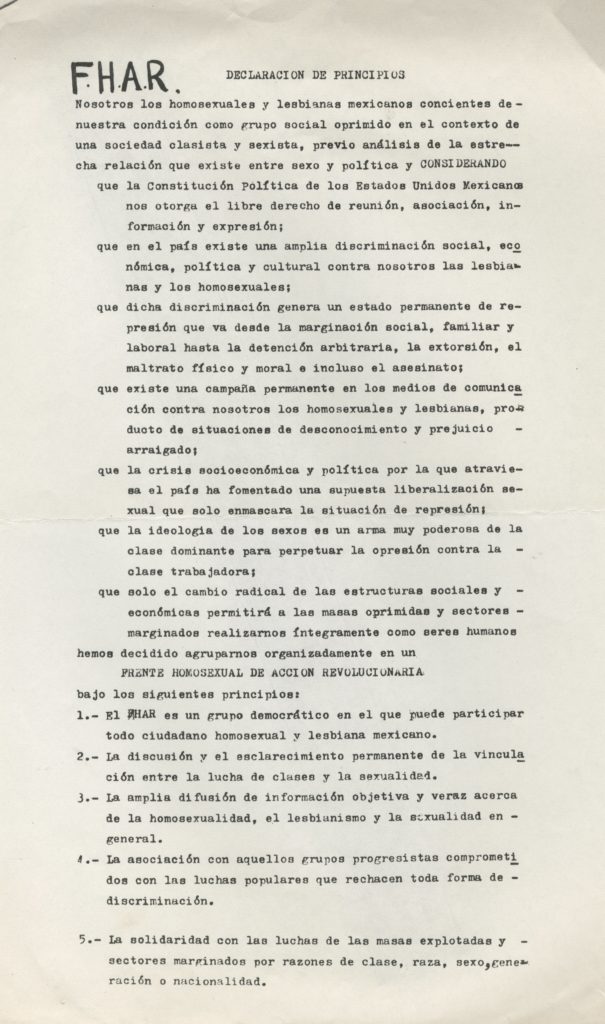

In their first outing, FHAR joined 5000 other marchers to simultaneously interrupt what they saw as the left’s investment in patriarchy and sexism and strengthen this transnational worker’s movement against capitalism and imperialism. By their second outing a few months later, on October 2, 1978, at the massive ten-year commemorative march for the students massacred at Tlatelolco, they were joined by more groups whose gay and lesbian activism was co-articulated with and against a broad base of existing left social movements, rallying around the call “por un socialismo sin sexismo” [for a socialism without sexism]. For example, FHAR was joined by Oikabeth (“warrior women who open paths and scatter flowers”) whose first objective was “to abolish the patriarchal capitalist society which is based in labor and sexual exploitation” and who fought for what they called the “quadruply exploited: belonging to a country colonized by imperialism; as workers by the capitalist class; as women by patriarchal domination; and as lesbians by the imposition of heterosexual society”; 6 and Grupo Lambda de Liberación Homosexual, gays and lesbians whose “sexual-political work” (“trabajo sexo-político”) and “struggle is not separate from the rest of the oppressed: workers, peasants, students, children, the physically and mentally disabled.” 7 In their statement of principles at the time, FHAR identifies as “gays and lesbians conscious of our condition as a social group oppressed by a classist and sexist society” who recognize that “the socioeconomic and political crisis in the country has created a supposed sexual liberalization that only masks the situation of repression” [see fig. 1] 8 – an analysis of the effects of the earliest experiments in brutal economic and social neoliberalism in Latin America, whereby discourses of sexual freedom (flexibility or liberalization) work to both mask and administer techniques of modern colonial biopower, that seems to presage what those of us grappling with the much later effects of neoliberalism in the Anglo northern Americas have come to call sexual exceptionalism or homonationalism 9 – and so aligned their struggle with all those “exploited and marginalized for reasons of class, race, gender, generation or nationality.” 10 What we see from the earliest forms of activism around sexual politics in Mexico is an insistence on recognizing sexuality as just one more effect of power, not the singular or most important site of power, and on situating these local struggles in a transnational context structured by colonialism, capitalism and patriarchy. 11

This double-orientation, to and away, with and against an event, institution, situation and/or social movement resonates not only with Ahmed’s killjoys, but also with the affective dynamics of what Muñoz calls “disidentification”:

[t]he process of disidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that both exposes the encoded message’s universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications. 12

We can see that FHAR, Oikabeth and Lambda were using this sort of disidentificatory strategy – simultaneously exposing the left’s exclusionary machinations and recircuiting the logics and politics to include and empower minority identities and identifications. But relajo also depends on and generates collectivizing, necessarily social and improvisational elements for which disidentification does not quite account. Portilla explains that the social, communicative and communitizing elements of relajo are “essential”:

relajo can only present itself in a horizon of community. The acts that contribute to constituting relajo are acts that presuppose an immediate communicative intention. If relajo is an attitude toward a value, it is also, in parallel fashion, an attitude that indirectly alludes to ‘others’…. Relajo is an invocation to others present…. Relajo in solitude is unthinkable…. It is constituted both by my lack of solidarity [with a value] and by my intent to involve others in this lack of solidarity, which creates a common environment of detachment before the value. 13

As an activist affective strategy, relajo works by not only suspending our solidarity with a certain value, but depends on calling others in to enable and prolong and multiply this suspension. Relajo hopes to interrupt our attachments to any institutionalized or established value, and redirect it to the only thing relajo cares about: ‘others.’ That is, while relajo might share with disidentification the capacity ‘expose’ exclusionary operations of power and ‘empower,’ its main interest is in scrambling our habitual and compelled orientations to value or power and enticing us towards new and unpredictable forms of communication, immanent community and collectively improvised relationality.

Indeed, the “horizon of community” upon which relajo depends is not fixed and has no stable state of being, it is created in “the intersubjectivity of those present” 14 through multiple iterations and variegated repetition:

Relajo is a reiterated action. A single joke that, for example, interrupts the speech delivered by a speaker is not enough to transform the interruption into relajo …. It is necessary for the interrupting gesture or word to repeat continuously until the dizzying thrill of complicity in negation takes over the group. 15

It is reiterative and repetitive, but also unexpected and non-identical in its repetitions, taking on a slightly different form or sound or meaning depending on the people who are dizzyingly thrilled into complicit participation. This dynamic, Portilla explains, is very different than teasing (choteo), sarcasm or mockery, which are unidirectional, individualized, instrumental, insulting, bitter and “deep down there exists in this individual a will to show his or her ‘superiority’ relative to the other individual.” 16 Relajo, on the other hand, is multi-directional, three-dimensional, good-natured, non-competitive and participatory: “the agent of relajo is ‘humble,’ tending to disappear and to hide behind the environment he or she has created, and this individual’s action is an inciter of the others’ action. The agent of relajo wants everyone to be an actor.” 17 Relajo describes the experience of feeling alien from the objects, people, institutions, situations, social movements, formulations of community that are supposed to embody any predetermined affective value. It also describes the experience of sharing that discordant sensation of alienation, ensuring that others feel a bit of it, not because it’s necessarily a better or superior sensation, and not because it necessarily leads to a better value around which to convene, but because it enables a shared detachment, if only for a moment, from the thing we’re all supposed to value, a queering of our orientation to a supposed good, and especially an illicit thrill of pleasure in that disorientation.

We can see this disruptive but collectivizing, inviting, participatory, reiterative and humble affective strategy aimed as much towards other gays, lesbians, gender and sexual dissidents as towards the ‘anti-homosexual’ working or ‘ruling’ classes. One of FHAR’s 1978 petitions to stop police raids and harassment invites signatories with the playful title, “You, yes, You Know a Homosexual… that’s the way it is”; and the homosexuals you know might be your co-workers, kids, relatives, friends and gays, lesbians, ‘fags’ [jotos], prostitutes, ‘vagabonds’ [vagos], homeless people, students, workers and anyone deemed ‘indecent’ or ‘suspicious.’ 18 The next year, FHAR’s invitation to join a protest against police brutality opens with a few lines of dialogue making fun of the “typical” conversation with gay and lesbian “compañeros”:

– Hey, you’re invited!

– To what? A party?

– No….

– So, to a drag show?

– No….

– Ah, I know, to a nightclub….

– No, not that either….

– Well?

– We’re inviting you to a protest against repression….

– No, little brother, look, I’m not interested in politics or trouble-makers, so I guess I’ll see you later… ciao.

– Hey, wait just a second! I’ll explain what it’s about….

– I just told you, I’m not interested in politics…. 19

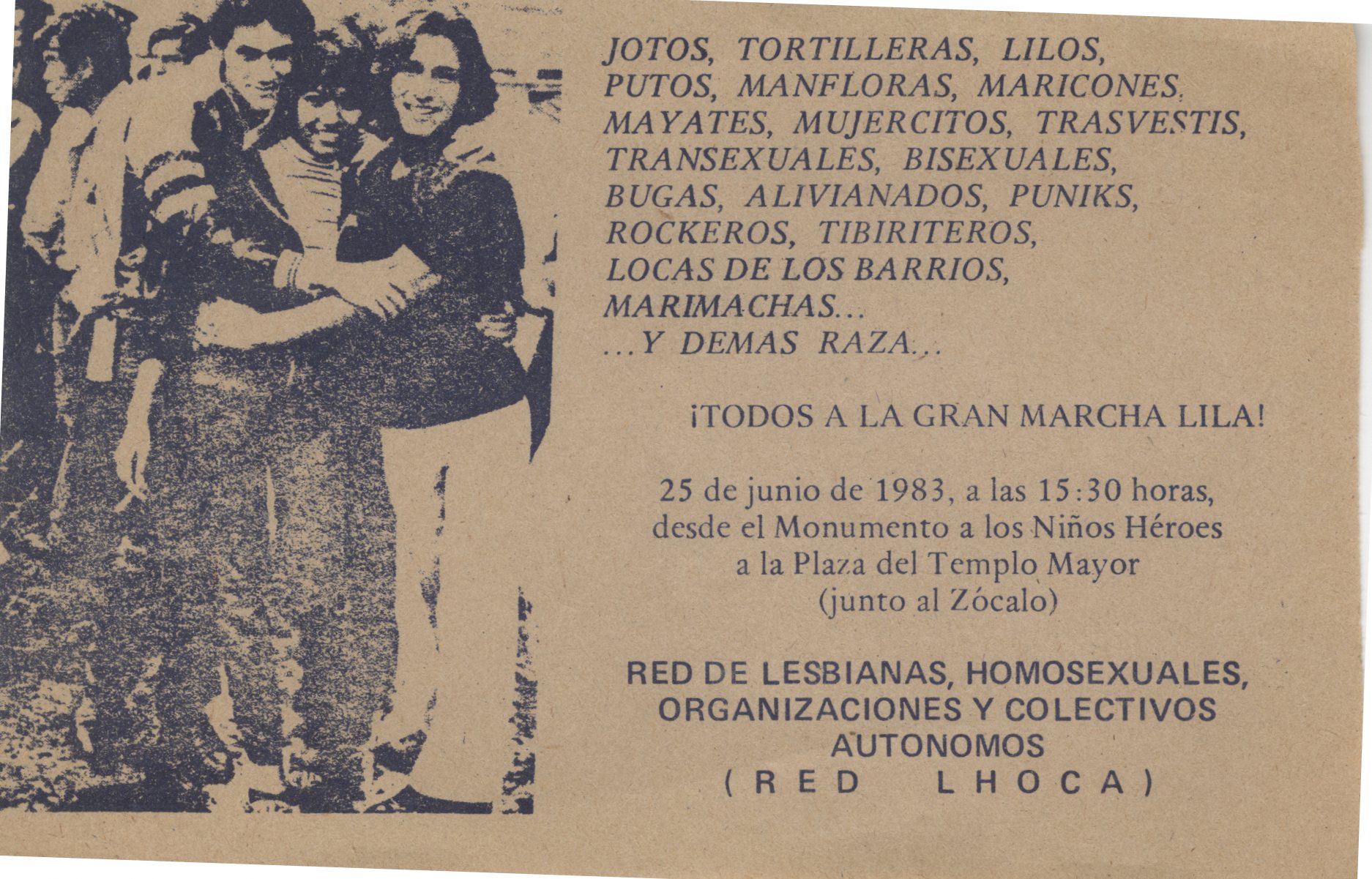

The conversation goes on – with the compañero insisting that they are not repressed and have no interest in “gay power” or “exhibitionism” or “trumpeting from all the windows that I’m a faggot [maricón]. Also, I’m no pinko-commie” 20 – but this good-natured caricature of apolitical gays is clearly oriented towards inclusion rather than insult. We see this affective strategy persisting in the flyer for the 1983 Pride march [see fig. 2], or “Great Fairy March” [Gran Marcha Lila] from Red de Lesbianas, Homosexuales, Organizaciones y Colectivos Autonomos (Red LHOCA which translates as “Crazy network”) – an organization whose name is designed as an acronym to make fun of itself – calling all “jotos, tortilleras, lilos, putos, manflores, maricones, mayates, mujercitos, trasvestis, transexuales, bisexuales, bugas, alivianados, punks, rockeros, tibiriteros, locas de los barrios, marimachas… y demas raza!” 21 Again we can see the activist gesture here is not exactly a reverse-discourse declaration of pride, not a direct confrontation with power, but an excessive accumulation of every discourse of social-sexual-class-race-gender stigmatization and regulation, playing up the absurdity of biopower’s over-production of unlivable lives.

These affective dynamics of relajo, in its multiplying ridicule of modern colonial seriousness, helped to grow public activism around sexual politics in Mexico from a small contingent at the 1978 marches for the Cuban revolution (July 26), for the life of Mexican insurgents and insurgence (October 2) and a transnational movement for a better “socialism without sexism” to thousands in the streets from Oikabeth, Lambda, FHAR, the Creative Community, Women’s Collective, Women’s Union and the Revolutionary Workers’ Party (PRT) at the first Pride march in Mexico City in 1979 (June 29). Just a few months later, in October of 1979, FHAR, Oikabeth and Lambda sent a delegation to Washington D.C., in the USA, to participate and lead workshops in the first Third World Gay and Lesbian Conference and form a contingent among the 250,000 marchers in the first Gay and Lesbian March on Washington. In a report published in the FHAR newsletter shortly afterwards, they note that the North American press coverage of the events were “very scant and unfavorable” and write, “we hope that the North American and international gay press come to give a more accurate account of what it means to have the presence of so many gays and lesbians (with delegations from Alaska and Hawaii, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia) in the heart of the most powerful and repressive country in the globe.” 22 FHAR throws relajo in its killjoy form here, refusing to simply celebrate this historic event. Simultaneously announcing the conference, march, limited media attention and refocusing collective attention away from the scale and success of the march towards the repressive power of the U.S., we get a sense from this short report of the critical calling-in that built the multifocal, dispersing, ridiculizing and multiplying assemblages of transnationally-oriented activisms around sexuality in Mexico.

Proyecto 21: “a fashion show”

Monsivaís suggests that queer activism in Mexico has been sustained by relajo since “the great raid” in 1901, by the ridiculization of power, turning the violence of social norms into a fashion show, “in the spirit of the interrupted party.” 23 While I’ve focused on the ways that this spirit informed activism in the 1970s, we can see that it lives on well into transnationally articulated activism of the twenty-first century. During the 2015 Pride march in Mexico City, for example, the performance art collective, Project 21 [Proyecto 21] [see fig. 3], organized a contingent for what they called a “catwalk against the grain” [Pasarela a Contrapelo]. 24 They joined the march in hand-made outfits crafted from urban detritus of old newsprint, plastic bags, blank papers, protest signs, tissue paper, plastic jewelry, duct and packing tape; they turned the corporatization and depoliticization of Pride into a fashion show, splashed in rainbow colors and blood red paint and emblazoned with messages demanding justice for the 43 students disappeared from Ayotzinapa, along with all victims of narco-state violence, including women and sexual and gender dissidents. This performance was also a joyously killjoy refusal to celebrate the Mexican Supreme Court’s June 2015 decision to effectively legalize same-sex marriage in every state of Mexico.

In the Facebook event page for this “catwalk,” Yecid Calderón writes,

This is an invitation that has no leaders. It’s for all the critical consciousnesses inside the sexual diversities in Mexico City…. This is an invitation, not to resentment [resentimiento] for resentment’s sake, but rather to re-feel [re-sentir] more and otherwise; an invitation not to symbolic violence and abuse between ourselves, those from below and the margins/fringe; but yes to criticism, to rebellion and to denunciation well based in the brazen way that the crudest capitalism (heteropatriarchal in essence) contaminates our diverse sexual battle…. This is a party, a journeyed day, a joy in the gathering, a camaraderie without limits. Come with good vibes and there will be a hug and a warm smile for you. 25

We can trace the spirit of relajo in the invitation to feeling otherwise, to a leaderless and collective suspension of the value of heteropatriarchal capitalism embodied by the institution of Pride, to a rebelliously joyful affective reorientation away from the goods of “capitalism, competitiveness, conflict, war, enmity, destruction, intrigue, coloniality, racism, classism, sexism, misogyny, transphobia, femmephobia, homophobia, lesbophobia, old-agephobia [gerontofobia] (humiliating and despising the elderly) and a great etc. of exclusions.” 26 We can catch a glimpse of Project 21’s interactive street theater during the march, performing a rendition of “The Other” 27 – composed by José Patiño, founder and organizer of the collective since 2005, who we see as their alter-ego, Alberta Cánada.

As their performance persona, Patiño calls in one of the provinces (Alberta) most renowned in Canada for its histories and ongoing practices of colonial, racial, gender and sexual violence, reminding us that these networks of state-sanctioned and practiced exploitation cannot be understood without a transnational analytic. Sung with a smile, “The Other” ridiculizes the internalization of patriarchal violence and (trans)misogyny, the compulsion to accept (tragar or ‘swallow’) and perpetuate cycles of violence, “to use our own chains to oppress others.” 28 During a pause in the song, Alberta Cánada walks towards the crowds riffing on Mexico’s suffering and compulsion to ‘swallow’ everything, from violence against gender and sexual dissidents to femicide 29 to state-sanctioned mass murder and disappearance of students, until ‘exploding’ (and ‘exploiting’, given the double or triple entendre of the word explotar) in the raucous and raunchy final chorus. Project 21’s interventions work by scrambling the affective orientation of the march away from proud celebrations of sexual and gender freedom with gestures not exactly of rage or shame (some of the activist affective responses to Pride with which we in the Anglo north might be more familiar) but a different tone of joy, a dispersed exhilaration in feeling otherwise, re-feeling (rather than resenting) relations with also precarious others, and with the precariousness whose unequal distribution is exacerbated and disappeared by such celebrations.

Project 21’s queer affective strategies recall those of FHAR, Lambda and Oikabeth in the 1970s – and if we consider FHAR’s warning that “supposed sexual liberalization only masks oppression,” so does their critical content – and resonate with at least 40 years of creative activism in Mexico that situates gender and sexuality in the context of colonial modernity and the transnational maldistribution of life chances. Of course we see it in the work of Jesusa Rodríguez – in performances like La Malinche – or any of those she and Liliana Felipe created during the 15 years that they ran the queer cabaret and theater, El Habito (1990-2005), and throughout their street-theater-style public activist collaborations that Rodríguez calls ‘mass cabaret.’ Laura Gutiérrez explains the ways that “the most important queer political cabareteros working in Mexico today: Astrid Hadad, Tito Vasconcelos, Ximena Cuevas, Regina Orozco and the artistic, business and romantic partners Jesusa Rodríguez and Liliana Felipe” 30 intervene in the structure of feelings that constitute transnational mexicanidad (articulated most iconically in post-revolutionary melodrama) to perform “relajo at its finest” 31 – interrupting by making dizzyingly hilarious densely complex beautiful and loving fun of the gendered, sexualized, racialised, colonial, political and economic violences that these structures enable.

By paying attention to the ways that this dissident affect has been thematized and practiced in Mexico, we can begin to recognize the ways that it gets used and the work it does elsewhere. We might see that queer relajo is not only the affective method by which gender and sexuality are coarticulated within transnational anti-capitalist, decolonizing and anti-imperialist creative activism in Mexico, but also the activist-academic method that might allow us to feel, follow and sustain the connections between conventionally separated activist affects and efforts. Attuning ourselves to the long history and contemporary life of queer relajo in Mexico might open us to sensing, connecting and naming these uncivil, rebelliously joyous, libidinal affective tissues, disparate sexualizations that won’t cohere to any sexuality, ‘against the grain’ of dominant or institutionalized feelings across transnational contexts.

- “Los homosexuals concientes hemos decidido salir a la calle en esta marcha con todos los oprimidos del país, aún a sabiendas de que las actitudes antihomosexuales no son privilegio a la clase dominante.” FHAR flyer, ca. 26 July 1978, Centro de Documentación y Archivo Histórico Lésbico Nancy Cárdenas (CDAHL), Fondo I, Centro Académico de la Memoria de Nuestra América (CAMeNA), Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México (UACM), Mexico City, Mexico. All translations from the CAMeNA collections are my own.[↑]

- Sánchez leaves relajiento untranslated, but offers an extended footnote to explain that in Spanish this “is a word with a decidedly pejorative ring” (Sánchez, The Suspension of Seriousness, 211 n. 13) [↑]

- Portilla, “The Phenomenology of Relajo,” 146.[↑]

- Ibid., 146–7.[↑]

- Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, 65-7.[↑]

- Oikabeth, Politica Sexual: Cuadernos de la Frente Homosexual de Acción Revolutionaria (1.1, ca. 1979: 21), Fondo I, CDAHL.[↑]

- Lambda, Politica Sexual (ca. 1979: 22), CDAHL.[↑]

- FHAR, “DECLARACION DE PRINCIPIOS,” ca. July 1978, CDAHL.[↑]

- See Puar, “Introduction: homonationalism and biopolitics,” Terrorist Assemblages, 2.[↑]

- FHAR, “DECLARACION DE PRINCIPIOS.”[↑]

- Of course these activist groups as well as those before and after them have exploited the porosity between relajo and more conventional political activism directed at policy, legal change and state recognition. For a more detailed and expansive discussion of the history of FHAR, Oikabeth and Lambda, and the political organizing and activism of other gay and lesbian organizations in Mexico, see Norma Mogrovejo, Un amor que se atrevió a decir su nombre: La lucha de las lesbianas y su relación con los movimientos feminista y homosexual en América Latina (México: Plaza y Valdés, 2000); Rafael de la Dehesa, Queering the Public Sphere in Mexico and Brazil: Sexual Rights Movements in Emerging Democracies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); and Jordi Diez, “La trayectoria política del movimiento Lésbico-Gay en México,” Estudios Sociológicos 39, no. 86 (2011): 687-712.[↑]

- José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 31.[↑]

- Portilla, “The Phenomenology of Relajo,” 132–3.[↑]

- Ibid., 132, 133.[↑]

- Ibid., 133–4.[↑]

- Ibid., 138.[↑]

- Ibid., 139.[↑]

- FHAR, “Usted, si, Usted Conoce un Homo,” ca. 1978, CDAHL.[↑]

- “¡Oye, te invitamos!/¿A qué, a una fiesta?/No…/Entonces ¿a un concurso?/No…/¡Ah! Ya sé, a un reventón…/No… tampoco…/¿Bueno…?/Te invitamos a una marcha contra la represión…/No manito, fíjate que no me interesan ni la política ni los borlotes, así que ai nos vemos… chao…/¡Oye espérate un momentito! Te voy a explicar de qué se trata…/Ya te dije que no me interesa la política….” FHAR “¡Oye, te invitamos!” ca. December 1979, CDAHL. [↑]

- “Ustedes los del gay power o como se llamen, nomás andan en el exhibicionismo. Mira maestro, yo no tengo ninguna necesidad de andar en esos rollos. Yo so libre, nadie me reprime ni tengo por qué andar pregonando a los cuatro vientos que soy maricón ni nada por el estilo. Además, no soy rojillo.” Ibid.[↑]

- “fags, dykes, fairies, male-whores, [several typically insulting Mexican colloquialisms for ‘dykes’ and ‘fags’], transvestites, transsexuals, bisexuals, straights, hippies, punks, rockers, tibiriteros [fans of tíbiri tábara, associated in Mexico with working class street parties, cumbia and a very distinct and brilliantly queer style of dance], crazy women from poor neighborhoods, bulldaggers… and every other breed!” Red LHOCA flyer, ca. June 1983, CDAHL/CIDHOM.[↑]

- “Las reseñas de la marcha en la prensa norteamericana fueron muy parcas y poco favorables. Esperamos que nos llegue la prensa gay norteamericana y internacional para hacer un recuento más acertado de lo que significó la presencia de tantos homosexuales y lesbianas (hubo delegaciones de Alaska y Hawai, de Australia, Canadá, México, Costa Rica, Colombia)

en el corazón del país más poderoso y represivo del orbe.” FHAR Informa 2, ca. December 1979, CDAHL.[↑] - Monsiváis, “luego de la Redada los homosexuales de la ciudad de México ya no se sienten solos; de alguna manera, en el espíritu de la fiesta interrumpida, los acompañan Los 41, la señal de la existencia de la tribu.” “Los 41 Y La Gran Redada.”[↑]

- Yecid Calderón, “Pasarela a Contrapelo, Locxs Anarco-Porno-Glam-Punk,” Facebook event, June 27, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/events/984489254924760/, last accessed January 21, 2016.[↑]

- “Esta es una invitación que no tiene líderes. Es para todas aquellas conciencias críticas dentro de las diversidades sexuales en la Ciudad de México…. Esta es una invitación, no al resentimiento por el resentimiento, sino más bien a re-sentir más y de otra manera; una invitación no a la violencia simbólica y al maltrato entre nosotrxs, las de abajo y del borde; sí a la crítica, a la rebeldía y a la denuncia bien planteada por la descarada forma como el capitalismo más crudo (heteropatriarcal en esencia) contaminó nuestra lucha sexual diversa…. Esta es una fiesta, un día transitado, un gozó en el encuentro, una camaradería sin límite. Tu llégale con buena vibra, habrá un abrazo y una sonrisa acogedora para ti.” Yecid Calderón, description of Facebook event, “Pasarela a Contrapelo, Locxs Anarco-Porno-Glam-Punk,” https://www.facebook.com/events/984489254924760/.[↑]

- “Agitamos esta digna rabia contra un enemigo común, el heteropatriarcado en sus múltiples caras: capitalismo, competitividad, conflicto, guerra, enemistad, destrucción, intrigas, colonialidad, racismo, clasismo, sexismo, misoginia, transfobia, afeminofobia, homofobia, lesbofobia, gerontofobia (humillar y despreciar a los ancianos) y un gran etc de exclusiones.” Calderón, description of Facebook event, “Pasarela a Contrapelo, Locxs Anarco-Porno-Glam-Punk.”[↑]

- Alberto Patiño, YouTube video, June 30, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKFb3clljNM&feature=share%3Ehttps%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DNKFb3clljNM&feature=share%3C%2Fa%29last accessed January 20, 2016.[↑]

- Alberto Patiño, YouTube video: “el que usaba sus proprias cadenas para dominar.” [↑]

- For more on the concepts of feminicidio, femicidio and femicide, see Marcela Legarde, “Del femicidio al feminicidio,” Desde el Jardín de Freud 6 (2006): 216-225.[↑]

- Laura G. Gutiérrez, Performing Mexicanidad: Vendidas Y Cabareteras on the Transnational Stage (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010), 23.[↑]

- Ibid., 69.[↑]