Introduction

Contemporary public imagination continues to turn toward Catherine of Aragon as a go-between traversing political and cultural borders of Anglophone and Hispanic culture. In our current media landscape, these tensions have bubbled to the surface in the Starz’s 2019–2020 historical miniseries The Spanish Princess. Based on Philippa Gregory’s novels The Constant Princess and The King’s Curse, the Starz series is a sequel to the miniseries The White Queen and The White Princess. Starring Charlotte Hope as Catherine of Aragon and Ruairi O’Connor as Harry, the Duke of York and future Henry VIII of England, the series markets the story of the Tudor Queen to a new audience by re-envisioning Catherine in view of contemporary gender relations, as a powerful, assertive, and independent woman and monarch. The casting and styling of Charlotte Hope adapts historical descriptions of youthful Catherine’s beauty, deepening archival references to her “red gold hair” to a fiery dark red tint. In casting a white English actress to play the lead role, the series notably does not adopt colorblind strategies as does Channel 5’s 2021 Anne Boleyn series starring Jodie Turner-Smith. In The Spanish Princess, Hope’s staging of a foreign Spanish identity is mostly limited to her speaking English in a faux Spanish accent. Hope plays the Catherine as a passionate woman with modern feminist sensibilities that she suppresses for most of the series beneath the obligations of filial and marital duty. Series creators Emma Frost and Matthew Graham describe their reimagining of the Tudor queen as an attempt to “stand on the shoulders of the kernels of the facts that we have.” 1 In cultural imagination, queens are often invoked as border-crossers regarded with a volatile blend of idealization and suspicion. Arguably, Catherine of Aragon is among the most contested of these regal figures in early modern European history. While her virtues and queenly exemplarity led her to be claimed as a native daughter by the two national literatures, at times her representation in the historical texts and contemporary adaptations of both England and Spain are foreignized for dramatic or polemical effect. For instance, while Catherine holds a central place within the Anglophone cultural industry built around Tudor history, the title of the Starz series demonstrates how the contemporary Anglo-American media often packages her story by marketing her as “a Spanish princess.” 2 Similarly, Iberian cultural productions from Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s theatre to contemporary Spanish film and television tend to reclaim her as a devoted Catholic Spanish princess while mining her transnational cultural capital. In Iberia, Catherine’s foreign status is highlighted by the fact that her story has most often been represented when there is need of reinforcing Spain’s exemplarity for transnational audiences, whether it take the form of the Habsburg empire’s Counter-Reformation chessboard or contemporary clout within the European Union.

In this essay, I examine how the tension between Catherine’s foreignness and her domestication lends to her racialization in early modern literary sources: primarily Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s 1627 play, La cisma de Inglaterra, but also in reference to Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, alternatively titled All Is True. To explain a key term, I borrow “domestication” from translation theory to mean the kinds of cultural and linguistic adaptations involved in crafting the queen’s public image for the English public. I then compare early modern representations of Catherine (as her name is spelled in the play) with the 2019 Starz series, The Spanish Princess, which is marketed to its audience through the invocation of Catherine’s Spanishness but, nevertheless, tells the story of her Englishing over the course of its two seasons. An implicit facet of my argument is that these early modern and contemporary representations of queenship are connected through the longue durée of discourses on queenship, though it is not within the scope of this article to track Tudor queens’ representational genealogies over the centuries between Shakespeare and Calderon’s time and the Starz series. Instead, I foreground the polytemporal oscillations of racial imagery of royal women’s bodies by groupings readings from Shakespeare, Calderón, and Starz’s The Spanish Princess to analyze how racial imaginaries interwoven in the iconicity of queenship enable conversations between historical and contemporary cultural imaginations. I specifically read the associations of Catherine’s image with constructions of the foreign and domestic with racial imaginaries in the English and Spanish contexts by tracking the way her iconography implicates racialized binaries of light and dark. Race studies scholars have underscored the fluidity of early modern understandings of “race” – and consequently, “nation” – discussing how these frameworks shift with respect to contingent constructions of gender, geography, religion, family, and class. In her foundational book, Things of Darkness, Kim F. Hall has called attention to the way in which polarities of “light” and “dark” in early modern cultural production were tied to the racial imaginaries taking shape through the emergent slave trade and mercantile expansionism. 3 Hall has observed that these polarities were frequently incarnated in the representations of white women and racialized subjects such as Africans. Indeed, the trademark ambivalence that Lee Bliss has observed as characteristic to the political and moral messaging of All Is True also applies to its representation of queenship: 4 as fundamentally constituted through interlacing of the domestic and foreign, even when its representational apparatus is invoked to compartmentalize and contrast these two formations. Examining the way Calderón, Shakespeare, 5 and modern television dramas like The Spanish Princess employ gendered light/dark binaries to weave Catherine’s story into the broader political project of imagining the nation, I show how Catherine’s iconography is entangled in the crosshatches of Spanish and English racial imaginaries. Moreover, given that Catherine is associated with family and kinship networks that become ruptured through her divorce with Henry VIII, The Spanish Princess and its historical forerunners (namely Shakespeare and Calderón) closely bind Catherine’s image with the cultural representations of other queens: Anne Boleyn, her rival; Mary I, her daughter; Elizabeth I, Anne’s daughter and Mary I’s rival; and not to mention, Isabel I of Castile, her mother. In England and Spain, national imageries of queenship frequently pit Catherine against Anne Boleyn by harnessing and recasting racialized binaries of light and dark from the Reformation’s and Counter-Reformation’s polemical representations of royal women’s bodies.

Queen Catherine in Shakespeare’s All Is True

William Shakespeare and John Fletcher’s 1613 play, Henry VIII (All Is True), meditates on the ambivalent identity of the English body politic through the cultural memory of the Tudor queens who become symbolic to the political drama of the English Reformations. Royal consorts’ racial indeterminacy is tied to the oscillation of domestication and foreignization in cultural representations of their bodies. While Archbishop Cranmer’s prophecy over the infant Princess Elizabeth remains one of the most value-laden moments of the play, Catherine of Aragon’s portrayal as an exemplary English queen who is resolutely devoted to her husband, adopted country, and subjects continues to evoke considerable pathos. Scholars agree that All Is True’s sympathetic portrait of Catherine of Aragon operates by Englishing her. Glynne Wickham believes that Shakespeare’s very purpose in writing the play was to mount a defense of Catherine and to “redeem in the national interest the slanders cast in 1531 upon [her] name.” 6 Amy Appleford has observed that Shakespeare claims Catherine as an English queen who may hail from Spain, but who is thoroughly nativized to England to the point of embodying the reformist possibilities within English Catholicism. 7 Yet, while scholars have astutely analyzed the representational labor performed by Shakespeare and Fletcher’s play to align spectator sympathies with the repudiated Tudor Queen, they tend to downplay the tensions provoked by her foreign origins. During her divorce trial, when defending the absolution procured from Rome validating her and Henry’s marriage following the death of Prince Arthur, Catherine references the foreign origins of her natal nobility, she invokes: “My father, / Ferdinand, the King of Spain, was reckoned one / The wisest prince that there had reigned….” Nevertheless, during the same trial, Catherine refuses to speak to Wolsey in Latin, despite her well-known proficiency in the classical tongue (thanks to her humanist education at the court of Isabel I of Castile), declaring her desire to abjure “a strange tongue” in her preference to “speak in English.” 8 Shakespeare’s representation of Catherine corresponds not only with her crafting of an English identity after her marriage to Arthur and Henry, but also to her public image when growing up as an infanta (princess) of Spain. As Emma Luisa Cahill Marrón has observed, Catherine of Aragon was intended for an English marriage soon after her birth. Indeed, Isabel named her “Catherine” in honor of her own grandmother, the English Catherine of Lancaster, to pay homage to her English roots and signal this intended marital alliance. 9 However, from the Renaissance onwards, English and northern Europeans have tended to exoticize Spaniards as racially and culturally othered Europeans, given the long durée of Moorish rule in Iberia. 10 The Starz series taps into these stereotypes by presenting a fiery, passionate, cosmopolitan Catherine who sets in relief England’s “rigid social dogma and cultural homogeneity.” 11 Thus, they reinforce the fiction of a homogenous England which has been contested by recent scholarship foregrounding how immigration and multilingualism shaped Renaissance England. While the Starz production shows Catherine’s growing Englishness as she matures into her role as Queen over the two seasons, the choice to market the series as The Spanish Princess privileges her portrait as an Spaniard in ways that rehash northern European stereotypes of Spain. The drama of anglicizing Catherine of Aragon requires Starz to portray Henry VIII’s first queen in the first few episodes as an exotic Spaniard whose foreign glamor preconditions her incorporation within the English nation. Conversely (as I discuss later in the essay), her prestige as a English queen helps fuel Spanish productions’ imaginative hispanizing and reincorporizing of her in the Spanish state, as demonstrable in Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s Counter-Reformation play La cisma de Inglaterra (The Schism of England).

In The Spanish Princess and its source materials, Catherine is fashioned through interlaced formations of domestication and foreignness that come to be registered through colorist templates of dark and light. Ironically, Catherine’s dream vision heralding her death in Act 4.2 of All Is True coincides in literary and historical texts with her domestication as an English queen. This vision is redolent with light imagery: “six personages clad in white robes, wearing on their heads garlands of bays, and golden visors on their faces” hold a garland over her head and offer her deep curtsies, which cause her to make signs of rejoicing and hold up her hands to heaven in her sleep. The light imagery of the masque symbolizes her divine sublimation from the disorienting confusions of the political world around her. This death vision masque, nevertheless, coincides with Shakespeare’s insistent representation of her as indigenized to England. 12 In contrast, Shakespeare associates Anne Bullen (that is, Anne Boleyn) with exotic foreignness through the metaphor of transatlantic wealth. As the Second Gentleman observes of Henry VIII and Anne’s relations: “Our King has all the Indies in his arms, / And more, and richer, when he strains that lady.” 13 As scholars have remarked, the association of Anne rather than Catherine with the seductive but potentially corrupting wealth of the Spanish Americas is rather striking, given that Catherine’s dowry (replete with bullion sourced from the Atlantic world) was one of the motivations for King Henry VII to enter into a marriage alliance with Spain for his sons. And while it is Elizabeth I who is heralded in Archbishop Cranmer’s prophecy as embodying “a maiden phoenix” destined to usher in a new Golden Age for England, the spiritual and moral illumination from Catherine’s exemplariness as queen, wife, and mother competes with the Virgin Queen as the play’s emotional center of embodied charisma and nostalgia. As we shall see in the next section, Shakespeare’s strategies of imagining queenship are extraordinarily similar to Calderón’s, including the imagining of Catherine’s exemplarity in relation with other queens such as Anne Boleyn and through the racialized play of light and dark that mediates royal women’s ambivalent relationship to constructions of the domestic and the foreign.

Catherine’s depiction in Calderón’s La cisma de Inglaterra

Receptions of The Spanish Princess in Spain were generally negative, with most reviewers viewing the production as a species of Anglophone historical aggrandizement . “[L]a Historia de España está siendo ultrajada cada semana y nadie ha derrochado un tuit para salvaguardar la memoria de Catalina de Aragón” (Each week, the history of Spain is being outraged, and nobody has ventured a single tweet to protect Catherine of Aragon’s memory), complained Aloña Fernandez Larrechi in a review of the Starz series for Serielizados entitled “El despróposito histórico que solo sirve para indignarse” (The historical nonsense that only serves to anger). 14 Spanish reviewers tend to view English adaptations of Catherine’s story as an insult to Spanish history, thus indirectly claiming Catherine of Aragon as a daughter of Spain whose honor must be defended from the slant in English and American representations of her. Yet, Catherine’s sensational éclat in Spain’s printing and entertainment industry arguably rests upon her marital incorporation with England and her successful tenure as an English queen over many years. For instance, the second edition to Almudena de Arteaga’s 2009 biography is titled Catalina de Áragon: Reina de Inglaterra (Catherine of Aragon: Queen of England.) Similarly, Antonio Cavanillas de Blas’ 2020 biography is called Catalina de Aragón y Trastámara: Reina de Inglaterra. Such titles continue to market Catherine of Aragon as an English queen to a Spanish reading public. The interlacings of the foreign and domestic integral to Catherine of Aragon’s image shape her reception in Spain and Latin America as well as her perception in Anglo-Saxon cultural productions. These tensions rippling through contemporary receptions of the Spanish Tudor queen in pop culture can be traced to historical productions such as Calderón’s La cisma de Inglaterra (The Schism of England).

Pedro Calderón de la Barca is one of the preeminent figures of Spanish Baroque theatre; his influence upon Spanish culture and drama is often compared with Shakespeare’s analogous imprint upon Anglophone culture. The Spanish Renaissance play was called a comedia, and it usually featured 3 Acts called jornadas. As a number of scholars have pointed out, Calderón’s representation of Catherine of Aragon (called Reyna Catalina in the play) in La cisma de Inglaterra offers a number of intriguing correspondences with Shakespeare’s portrait of the repudiated Tudor queen in Henry VIII (All Is True). Over the three jornadas of La cisma de Inglaterra, Catalina’s representation is interlaced with and defined in contrast to that of her rival, Anne Boleyn (called Ana Bolena). The long-suffering Catalina is repeatedly described as a saint, a martyr, and an exemplary queen. Additionally, Catalina is the focal point for the emotional sympathies of the text. Once Henry VIII (called Rey Enrique) listens to the counsel of Cardinal Wolsey (called Cardinal Volseo) and makes the decision to repudiate Catalina in favor of Ana’s sensual charms, he resolves: “Padezca Catalina / por cristiana, por santa, por divina” (Suffer, Catherine / as a Christian, as a saint, as a divinity). 15 In quite a different mood after discovering Ana Bolena’s treachery and Catherine’s death, Henry’s repentant exclamation also offers a hagiographic portrait of the virtues of his former queen: “mártir generosa fuiste / dame favor, dame ayuda, / pues ya quiero arrepentirme!” (A generous martyr you were / grant me favor, grant me assistance / For I wish to repent!). 16 Like Shakespeare, Calderón portrays the repudiated Tudor queen as an exemplary Catholic martyr. In the final scene of the play, Calderón stages Catalina moral and political triumph, appropriating the emblematic dramaturgy of an auto-sacramental: Ana’s body, covered with a sheet, lies at the foot of Enrique’s throne, seemingly not deserving of a burial due to her flouting of moral and political laws. In this tableau, Enrique announces Maria (the future Mary I) as heir, standing alongside his daughter to symbolize the restoration of England’s Catholic succession. There is no mention of Elizabeth or Edward, though Catalina’s retinue of ladies in waiting does include Jane Seymour (called Juana Semeyra), the future mother of Edward VII. Calderón’s historical revisionism overwrites the reign of Elizabeth I, closing upon Mary I’s succession to foreground the continuity of Anglo-Spanish alliance and trans-Catholic harmony across continental Europe that Catherine of Aragon’s marriage was meant to cement.

The bodies of early modern queen consorts are charged with racial ambivalence for not only do they represent the lineages of their natal kingdoms, they also come to incarnate the shifting political and racial identities of the body politic into which they are incorporated through marriage. Calderón’s gendered interplay of oppositions between Catherine and her “Lutheran” rival Anne Boleyn in La cisma de Inglaterra serve to embody the clash of theological and political formations in state identity after the Reformations. (Spanish Counter-Reformation discourse characterized the different branches of English Protestantism, including Anglicanism, as “luteranismo” or Lutheranism). Catalina and Ana are not simply represented as queens but gendered embodiments of alternate theological futurities for schismatic England. Following the English Schism, literature has treated the queens bodies as representations of political and religious difference, and freighted them with gendered tropes and ideological meaning. For example, Calderón (similar to Shakespeare) presents Catherine not as a political player, but rather as “la perfecta casada,” the dutiful wife who provided an heir to the throne (albeit not a male one), and who embodied and performed the gender-specific virtues of patience, constancy, and, most importantly, chastity. 17 In La cisma de Inglaterra, the most prolific epithets used to describe Catherine by other characters, whether friend or enemy, are “santa” (saint or saintly) and “divina” (divine). In contrast, Calderón affiliates Ana’s Protestant faith with her representations of her vainglory, ambition, and disrespect for the natural, social, and political hierarchies of the body politic. For instance, in the beginning of the play, when Ana has just returned from the French court, we are given a portrait of her from the eyes of her admirer, the French Ambassador Carlos. After describing her beauty and grace during his recollections of her in the French court, he admits:

Su vanidad, su ambición,

su arrogancia y presunción

la hacen, a veces, esquiva,

arrogante, loca y vana;

y aunque en publico la ves

católica, pienso que es

en secreto luterana 18(Her vanity, her ambition,

her arrogance and presumption

make her, at times, disdainful

Arrogant, imprudent and vain;

and although in public you see her

as a Catholic, I believe she is

a Lutheran in secret.)

Ana’s secret heresy corresponds with her insatiable craving for power and her refusal to show deference to natural and social hierarchies in which she is positioned. Her admirer’s assessment is prefigured earlier in the jornada when she flies into a rage before her father on having to curtsy to Catalina.

¿A qué Imperio me has traído

donde, ceñidas las sienes

de rayos del sol, me vea

adorada de las gentes,

para decir que procuras

mi aumento? Llegar a verme

a los pies de una mujer,

¿qué gloria, qué triunfo es éste?

¡Yo la rodilla en la tierra! 19(What empire have you brought me to

Where my temples are wreathed

with the rays of the sun, where I see myself

Adored by all the people

That you can say you seek me

My advancement? Only to then see myself

At the feet of a woman

What glory, what triumph is this?

I with my knee on the ground!)

Ana’s refusal to accept the authority and power of the Reyna Catalina is emphasized at the beginning of her invective by her self-image as wreathed with the rays of the sun, appropriating Baroque symbol par excellence for divine kingship. Even while La cisma de Inglaterra expunges all mention of Elizabeth I, a number of critics have read Ana as an embodiment of Elizabeth Tudor, a prefiguration of the heretical excesses and political ambitions that Counter-Reformation rhetoric invested the last Tudor monarch with. Ana’s angry outburst gives a foretaste of the future Protestant queen’s embodiment of the empire that she will preside over, from the perspective of Spaniards: ambitious, piratical, grasping, avaricious, that will compete with Spain for continental influence and transatlantic power. The staging of Ana’s symbolic death at the end of the play, after she is killed by order of the king and repudiated by her kin for misleading the body politic, has associations with the Biblical story of Jezebel; “Jezebel del Norte” was also Elizabeth I’s epithet in the propaganda sponsored by Philip II. Ana’s imperious desire to reign over the kingdom of fierce beasts and brutes rather than to bow to another majesty symbolizes the chaotic, anarchic forces of Protestantism that will distemper the natural order of Catholic England’s body politic, as represented by Calderón’s saintly Reyna Catalina. This highly ideological portrait of Catalina and Ana appears to break from the transnational fashioning of Catherine’s image as infanta of Spain during the reign of Isabel I of Castile and to nationalize and racialize the two Tudor queens through their embodiment of Counter-Reformation dualities.

In Calderón’s play, the politicized oppositions between Catalina and Ana are racialized through the imagery of light and dark. As Kim F. Hall has observed, race in early modern contexts is often negotiated through embodied polarities of light and dark as interlaced with the unstable embodiments of values such as purity, chastity, and beauty. 20 Moreover, in the context of the Spanish comedia, light and dark are also tied to the politics of representation of Baroque philosophical and symbolic drama. 21 The sun is an image of ascent, ambition, success, reason, spiritual salvation, and monarchic power in Calderón’s plays. 22 It is often paired with the Night, as an image of descent, confusion, spiritual corruption, and forces anarchic to the body politic, including jealousy, vengeance, and heresy. 23 Through manipulation of light and dark, Calderón’s plays often stage the chiaroscuro realms of the indeterminacy where the conflicts between the characters allegorically stage the encounters between reason and passion, state and anti-state, Counter-Reformation Catholicism and Protestantism. In La cisma de Inglaterra as in his other plays such as La vida es sueño (Life Is a Dream) and El médico de su honra (The Surgeon of his Honor), characters’ embodiment of these polarities of light and dark also structure the racial fault lines of the subject matter. In La cisma de Inglaterra, Calderón uses a chiaroscuro palette to represent Rey Enrique’s struggle over his queens’ gendered embodiment of Catholicism and Protestantism. Through the play of light and dark, England emerges as a perilous space where the confusions and shadows of heresy permanently alter the political and spiritual genealogies of the English bodily politic.

The imagery of light and dark as associated with the Ana and Catalina interlaces the gendered imagery of the two queens with transnational imaginings of territoriality and nationality. On the surface, it seems as if Calderón’s representation of Catalina serves to territorialize her as Spanish, affiliating her with the representational codes used for the Spanish monarchy. These codes are used by her sympathizers and followers, establishing her as the moral focal point in the world of the play. However, the transnational framework of Catherine’s cultural memory and political significance ultimately works to put pressure on Calderón’s desire to protect and recuperate a “national” Tudor queen. As an example, after Ana angrily rebels against kissing the hand of Reyna Catalina following her return to the English court from France, her father, Tomás Boleno, exclaims she must look to the exemplary model of her Queen. The contrast between Ana and Catalina emerges through the play of metaphors of light used by Boleno to represent the Catholic Queen of England:

Mas, puesto que cuerda eres,

sabe vencerte; pues hoy

te ponen un transparente

cristal en la Reina santa,

mírate en él. 24(But as you are sensible,

Learn to control yourself; since today

A transparent mirror has been set before you

In the shape of the saintly Queen,

Look and ponder upon it.)

Boleno’s words repeat Counter-Reformation tropes of Catalina as a Catholic saint. Moreover, the imagery of light is referenced in his injunction to Ana to gaze upon the clear, transparent mirror embodied by Reyna Catalina: the glass is implied to refract light, for otherwise, Ana would only gaze upon an image of herself. The image of clear glass transmitting reflected light from (presumably) the sun racially allegorizes as transparency of the Queen’s embodiment of Catholic faith, caritas, and the domestic virtues of la perfecta casada (the perfect wife). However, the solar light she is reflecting is not that of the sovereign to whom she is wedded: the beginning of the play has already established the ominous portents of Enrique’s theological and erotic entanglements with Lutheranism. This is a critical deviation from the codes of monarchic representation in Baroque drama. As part of the iconography of Baroque theater, the Spanish Catholic sovereign is usually represented as the sun reflecting the life-giving properties of divine faith and terrestrial power, whose light is refracted by his household and court. Thus, the light reflected by Catalina’s mirror is disassociated from the body politic into which she has been wedded. Instead, the light, apparently coming from the Spanish Catholic kingdom of her origins, represents the continuum of absolute monarchy lauded by the Counter-Reformation sensibilities of Spanish Baroque theater as representing God’s will and the true doctrine of Christ’s Church upon earth. In essence, the light embodied by Catalina is nationalized as Spanish, associating the images of clarity, luminescence, and peace with her Catholicism and Spanishness. While Shakespeare’s Henry VIII domesticates Catherine as an exemplary English queen, the racialized representations of light in Calderón’s theater labors to nationalize Catalina as of Spain’s terrestrial and spiritual provenance.

La cisma de Inglaterra is also aware that its impulse to domesticate Catherine as Spanish goes against the grain of the historical record, which documents the infanta as being reared from infancy to become the Queen of England. Isabel I of Castile named her daughter for her own English grandmother, Catherine of Lancaster. 25 Isabel had intended her daughter to wed Prince Arthur and accordingly educated her in English, as well as in French and Dutch. 26 Even after Catherine’s divorce from Henry and the English Reformation, her cultural memory in Spain continued to bear symbolic echoes of the political value of the Anglo-Spanish alliance that her cross-border marriage was intended to cement. On the one hand, the light imagery that Calderón associates with Catherine appears to exert a centripetal force towards Catholic Spain, implying that Catalina’s saintly death operates as a kind of spiritual repatriation to her natal homeland. However, the play’s ending reverts to insisting on her cultural and political capital as a border-crossing Anglo-Spanish queen. The enigmatic final scene of the play anachronistically depicts Enrique VIII (Henry VIII) repenting his divorce with Catherine and crowning Princess Mary as his heir. Given the fact that Calderón’s play establishes the allegorical equivalence of mothers and daughters, this staging of Enrique choosing Mary to be his successor (rather than Edward) imaginatively reinstates Catherine’s spiritual and political power over England. Going against the historical record, Calderón’s ending to La cisma de Inglaterra shapes a politically significant vision of English sovereignty restored to and emotionally aligned with the Catholic body politic represented by Catherine. Thus, Catherine’s death in the play has the ironic effect of amplifying the political objectives of her transnational marriage, reiterating Anglo-Spanish links despite the historical evidence of the English schism and Anglo-Spanish naval war under Elizabeth I.

In La cisma de Inglaterra, Catherine’s queenship continues to embody the tension between domesticity and foreignness in the scenes following her death. The Spanish playwright represents Catalina’s death in La cisma de Inglaterra into a form of racial and political purification that restores the queen to the sphere of divine luminescence which the Spanish monarchy represented in the terrestrial dimension. As such, Catalina’s death serves to remove from the corrupted English body politic, purifying and re-nationalizing her as Spanish. When news of her passing is brought to Rey Enrique VIII by his daughter Maria, he exclaims:

¡Ángel hermoso!

que en trono de luz asistes

y en tu venturosa muerte

mártir generosa fuiste 27(Beautiful angel!

Who ascends to a throne of light

And in your venturous death

You were a generous martyr)

As in Shakespeare and Fletcher’s All Is True, Catalina’s death transforms her into a luminous symbol of transcendence above the divided, shadowy political world that has destroyed her. The images of beauty, light, and clarity racially distinguish the deceased Catalina from an England which has been irreparably corrupted by the effects of Enrique’s temptation by Protestantism, as embodied by Ana Bolena. In Calderón’s play, the Baroque colorist palette of light and dark etches the contrast between an orderly, divinely guided England within the Spanish, Catholic sphere of influence and England, blinded by shadowy confusions of heresy. Yet, Calderón’s resort to historical fiction – his imaginative staging of Catherine’s posthumous moral as well as political triumph in Henry VIII’s court through the Tudor king’s repentance of his treatment of his Spanish wife and election of their Catholic daughter as heir– works to undermine the stark binaries pitting England against Spain. The play’s ending imaginatively reinforces Catherine of Aragon’s transnational mobility across Anglo-Spanish borders, which continued to inform the historical image and cultural value of her queenship for Calderón de la Barca’s Spain.

In contrast with Catalina, Calderón repeatedly associates Ana Bolena with images of anti-light – that is, of shadow and monstrosity. Along the spectrum of anti-light images, Ana is also associated with the imagery of burning, consuming fire. Upon being reunited with Carlos, the French ambassador who had been her suitor during her sojourn at the French court, Ana makes a speech in which she clearly identifies herself as such a flame. While Carlos’ language uses Petrarchan imagery of sunlight to praise his lover’s beauty, Ana’s deprecating self-description turns to the imagery of fire, composed of ember and smoke and devoid of any intrinsic light:

pues soy una llama fácil

entre dos suspiros leves ….

que con el uno se apaga,

y con el otro se enciende ….

el fuego es pavesa, es humo,

hasta que tu aliento vuelve

a darme luz… 28(For I am an easy flame

Suspended between two light sighs

One extinguishes it

And the other lights it …

Fire is ember, it is smoke

Until your breeze returns

To give me light)

The imagery of flame suspended between two sighs speaks to the non-generativity of Ana Bolena as a corrupted source of illumination that cannot propagate itself on its own. Here too, Ana’s representation is layered over Spanish polemic against Elizabeth I, whose failure to propagate her lineage unfavorably contrasted with the Habsburg princesses represented in Spanish discourse as more worthy of inheriting her throne. The imagery of embodied flame also closely mirrors the language that Rey Enrique uses to describe his attraction and desire for Ana: she literally incarnates the fires of passion and Lutheran deviance that spurs his loss of sovereign self-control. The imagery of Ana as embodied flame layers the humanist suspicion of passion and desire in the mortal body upon the broader destruction that her and Enrique’s liaison will cause to the domestic family, court, body politic, and international alliances upheld by his marriage to Catalina. In her speech to Carlos, Ana also describes her embodiment of fire as composed of smoke and ember, signifying the loss of sight and orientation alongside the threat of destruction. The smoky “false light” embodied by Ana is repeated in Enrique’s speech denouncing her towards as a false queen towards the end of the play. In the scene where he discovers her incest and treachery and orders her arrest, he castigates her as “fiera,” “ciego encanto,” “falsa esfinge,” “basilico,” “áspid”, and “airado tigre”29 (wild beast, blind enchanter, false sphinx, basilisk, asp, angry tiger). The falsity embodied by Ana is gendered and theological: The speech reinforces the theme of blindness introduced through the imagery of Ana as a smoky flame by characterizing her as a “blind enchanter” and a “false sphinx” who proclaims fictious prophecies. Enrique’s speech quite literally depicts Ana as a monster, contrasting her with Catalina as the beatified saint. In this scene, Calderón channels Counter-Reformation rhetoric against Protestantism through the gendered language of monstrosity that the Renaissance world used for unruly women.

When Ana rebels against showing fealty to Catalina in Jornada I, she exclaims: “¡Yo besar con rostro alegre / la mano a la Reina, aunque de cuatro Imperios lo fuese!” (I kiss with a cheerful face the hand of a Queen, though she be of four empires!). Her hubristic exclamation ironically pays tribute to Catalina’s lineage; Calderón’s dramatic irony makes the point that Henry’s divorced queen is indeed affiliated with four regnal families, those of Portugal, Spain, England, and Austria. Ana’s words reinforce the emblem of royal kinship that is integral to the iconography of Catalina’s queenship by implicitly evoking her exalted lineage through the iconographic figure of her mother, Isabel la Católica, and her sisters, all of whom became queens over the thrones of continental Europe.

Catherine in Starz’s The Spanish Princess (2019–2020)

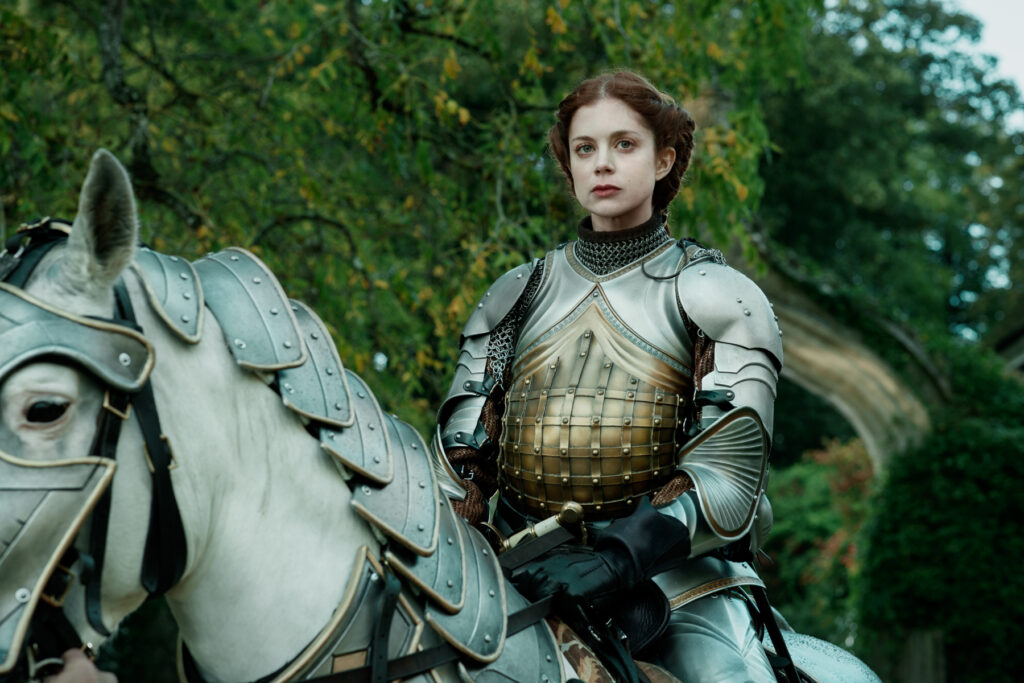

As Shakespeare and Calderón illustrated, early modern queenship is performative: the symbolic cargo of royal women’s bodies is influenced by how they define and traverse distinctions between the domestic and foreign. In The Spanish Princess’ “feminist” adaptation of Catherine’s story, this dynamic influences perhaps the most commented-upon moment of the drama: when an armor-clad Catherine herself joins the Battle of Flodden, leading the vanguard of the English army repelling the invasion from Scotland. 30

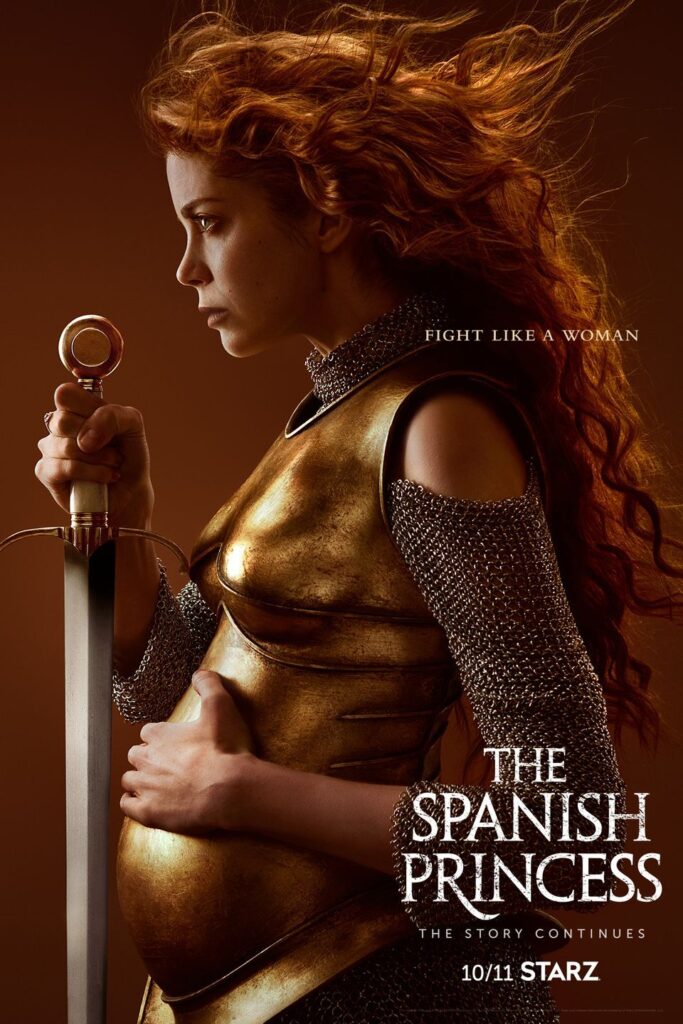

Emma Frost and Matthew Graham have discussed how their departures from historical record have allowed them to produce The Spanish Princess as a feminist version of Catherine of Aragon’s story. “I think we allow those historical facts to be a springboard into telling a story that is vibrant, and also that always has to have a relevance for the twenty-first century audience, because those are the people we’re making the show for,” Frost explains in a 2 November 2020 interview with Town & Country magazine. 31 However, the series actually bears considerable thematic similarities with its source material. Like the historical sources, both Spanish and English, the miniseries is rife with contradictions regarding the image of Catherine of Aragon as a border-crossing royal who has been claimed by and othered within both England and Spain. As in the historical sources, both Spanish and English, Catherine is imagined in conversation with the iconography of Elizabeth I, the quintessential English queen whose gendered image continues to loom over England’s cultural cartography like the Ditchley portrait. The tension of Catherine’s belonging as both Spanish and English is played out through imagery in omens, dreams, and predictions that are shaped by the historical tautology of the Reformation. One of the promotional posters released for the second season of The Spanish Princess references the Battle of Flodden scene, depicting Catherine with a sword and girded for battle: her long red hair is loosened, her arms are wrapped in chain mail, her breasts and belly are clad in shining golden armor. The iconography of the image evokes the promotional posters for Shekhar Kapur’s 2007 biopic, Elizabeth: The Golden Age, where Cate Blanchett’s red hair is loosened over her silver armor, as Gloriana takes the field to muster her troops to repel the Spanish armada. The poster for The Spanish Princess samples but also presents a counterpoint to many of the iconographic cues associated with Elizabeth I. The poster uses military accoutrements to portray her as another English warrior queen defending England from invaders (this time, the Scots not the Spaniards). In the promotional materials of both productions, the armor is luminous, reflecting light from the queenly bodies to show their exalted lineage and martial spirit. However, in the poster for The Spanish Princess, Catherine wears a bright, gold-colored armor, which is molded to show off her pregnant belly. This image contrasts with the promotional poster for Elizabeth: The Golden Age, which offers a representation of Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen clad in a silver-colored armor symbolizing purity and chastity. Both posters channel the associations made by historical sources between the queens’ bodies and light. The shining armor worn by Catherine and Elizabeth in the posters (and in the series and film) quite literally reflects light, associating the queens’ bodies with tropes of luminescence, clarity, earthly wealth, and divine favor. However, Catherine’s golden-colored armor covering her pregnant body departs from the silver and white iconography of the Virgin Queen by linking the Spanish Tudor monarch with maternity and family. Here, the series parallels Spanish sources such as Calderón’s La cisma de Inglaterra to show that Catherine, as opposed to Elizabeth, was biologically reproductive, fulfilling in some measure the traditional gender roles of wife, mother, and daughter. While Catherine symbolizes domesticity far more than Elizabeth, the gold color of her luminous armor also offers an exotic reminder of her foreign origins by evoking the lucre of transatlantic wealth that her dowry brought to English coffers.

In The Spanish Princess, the imagery of light in Catherine’s fashioning as warrior queen in the Battle of Flodden scenes is prefigured in the opening scenes of season one, episode one, through Frost and Graham’s representation of her mother. In the opening scenes of the series, Queen Isabel the Catholic (played by the legendary Alicia Borrachero) is shown leading her army in battle to quell a Morisco uprising threatening Catherine’s procession traveling through Spain to embark for England. Queen Isabel, clad in bright golden colored armor and with hair braided in the fashion of a Gothic queen, leads the charge against Muslim inhabitants of Iberia at the head of her army (Ferdinand is nowhere in sight in the scene). Before the charge, Catherine offers to join her mother in battle, reminding her that she has accompanied her during many campaigns of the Reconquista. However, Isabel stops her, reminding her daughter that her duty is to wed the English prince and alongside her sister Juana, who has married the Habsburgs of Burgundy, to form a circle of protection around Spain: “Sois de mi sangre. Una auténtica infanta de Castilla y un día, Reina de Inglaterra” (You are of my blood. An authentic princess of Castile and one day, Queen of England), Isabel tells her. Catherine assents and steps back, but her furrowed brow suggests that her mother’s advice has introduced a conflict in her spirit. Isabel then seats herself on her white horse, places a golden crown embellished with rubies over her helmet, and with the bright sun glinting on her golden armor, leads the vanguard hold aloft her sword. Catherine, kneeling as if in prayer, but the words she repeats over and over (in English) indicates the nature of the contraction: “Daughter of Spain. Queen of England. Wife to Prince Arthur.” The fact that her mother’s appellation has replaced her litany indicates the tension inherent in being “Daughter of Spain” and “Queen of England.” Even so, through similarity of images of light embodied in mother and, later, daughter dressed in iconic golden armor, The Spanish Princess suggests the Spanish exemplar for Catherine’s fashioning in the Flodden scenes as an English warrior queen.

While Spanish texts such as Calderón’s represent Catherine as intrinsically Spanish, English cultural memory insists on her as English. Just as Shakespeare domesticates Catherine to English body politic, Catherine’s arc in the The Spanish Princess depicts her as becoming rooted to and incorporated within England. In season two of the series, King Ferdinand of Spain manipulates Henry and Catherine to invade Navarre and secure his territories in the Basque country with English armies who believed that they were there to join forces with Spain to invade France. Soon after this betrayal, Henry and Catherine’s infant son dies. After the baby’s funeral, Catherine makes a speech to the assembled mourners. Dressed in black dress and veil, she declares,

“Why do I speak and not the King? Because your pain is mine …Our innocence is lost and our new wisdom forged in pain and grief …We have lost our precious son, and we have also lost our dignity to Spain. My father wrote to gloat of his victory, but I will tell you this. We do not drown when we feel grief. We do not shy from our mistakes, and we do not stand to be betrayed by allies. We called you here because the whole of England must know this. I am reborn! I am English! God Save King Henry.”

In this scene, The Spanish Princess shows that trials of grief and suffering have forged a strong, independent woman who thinks for herself and is free to choose her own identity. Her sufferings and awakening have become a baptism that has caused her to renounce her Spanish affiliations and to become naturalized, by choice, to England. This naturalization is reflected in Catherine’s sartorial fashioning henceforth from the series: the richly patterned fabrics she has worn will be replaced by more subdued Tudor textiles. Over the arc of its two seasons, The Spanish Princess portrays Catherine’s nationalization as coinciding with her feminist awakening, forging an English queen from the Spanish princess. The Starz production thus correlates Catherine’s gradual Englishing over the two seasons with her increasing feminist agency and power to think critically in ways that can conflict with her obligations as a wife and daughter. By implication, this assigns feminist agency with Catherine’s English acculturation vis-à-vis her Spanish heritage. Thus, while Catherine is left tragically alone by the show’s end, the gradual awakening of her feminist agency and powers of critical thinking signals that the Englishing of the Spanish princess has been a kind of redemption after all.

The Starz series also invokes the play of light and dark in its story of Catherine’s refashioning as a feminist English icon vis-à-vis Henry VIII’s descent into tyranny and domestic violence. As Catherine’s bond with Henry fractures, she finds solace in loyal female companions such as her Muslim serving woman, Lina, and courtier, Margaret Pole, as well as in her daughter, Mary. In the final episode of the series, Catherine informs Henry that she will separate from him and live in Malvern Court while remaining his wife, informing him that it is her choice to leave his household because she can see that he no longer loves her. In the final scene of the series, Catherine is dressed in the black wimple and dress depicted in her portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, leading Mary away to a new life together as Henry begins anew with Anne Boleyn. In a 29 November 2020 interview with Entertainment Weekly, Frost and Graham return to the gendered tropes of queenliness defined against versus monstrosity, with the monster this time being not the “other woman” but, rather, Henry VIII as the abuser:

What we felt was Catherine had been so maligned by history, it would be lazy, dramatically, and boring, historically, if we ended up in a place where she is a victim, where she’s beaten down and defeated by this man who she loved turning into a brute. I don’t think a 21st-century female audience wants to see a story where their heroine is vanquished by the end. What we felt was while the Tudors around her descend into madness, Catherine rises above it. She finds peace. She finds her own inner center through God, through her devotion to her daughter, and through love. 32

Light is used in the cinematography of the final scenes to contrast between Catherine as the proud, resourceful woman who walks ahead to begin a new life with her daughter and away (for the time being) from Henry VIII’s tilt into misogynistic madness. As Catherine walks away with Mary across the palace gardens towards Malvern Court, the cold outdoor light streams over her black velvet clad figure, setting it in relief against the verdant greenery. The lit, open vistas symbolize the freedom of thought, opinion, and conscience that Catherine has claimed in rising above her circumstances. This is reinforced by the more overdetermined symbolism of Catherine and Mary setting their caged parrot free in the gardens as they walk away from Henry VIII, who is on the path towards reinventing himself as an abuser of women and the body politic. This #MeToo awakening has taken place at the expense of Catheriene’s marriage but also of her Spanish heritage. Their scenes cut away to the darkened, smoky interiors of the Tudor palace where Henry VIII is carousing with Anne Boleyn. Over the arc of her Englishing in the series, Catherne of Aragon continues to bear value to her adopted nation by being reimagined as an icon of #MeToo, illustrating how border-crossing queens become the avatars of the political and social concerns of their nations and, as such, continue to be reinvented and reimagined across deep time.

Works Cited

Appleford, Amy. “Shakespeare’s Katherine of Aragon: Last Medieval Queen, First Recusant Martyr,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 40, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 149–172, esp. 152.

Barca, Pedro Calderón de la. La cisma De Inglaterra, ed. Francisco Ruiz Ramón (Madrid: Editorial Castalia, 1981).

Bliss, Lee. “The Wheel of Fortune and the Maiden Phoenix of Shakespeare’s King Henry the Eight,” ELH 42, no. 1 (Spring 1975): 2–3.

Cahill Marrón, Emma Luisa. Arte y poder: negociaciones matrimoniales y festejos nupciales para el enlace entre Catalina Trastámara y Arturo Tudor (PhD Dissertation: Universidad de Cantabria, 2012): 11

Fuchs, Barbara , Exotic Nation: Maurophilia and the Construction of Early Modern Spain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

Glynne Wickham, “The Dramatic Structure of Shakespeare’s King Henry the Eighth: An Essay in Rehabiliation,” Proceedings of the British Academy 70 (1984): 149–66, esp. 165.

Hall, Kim F. Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995): 62–122.

Halleman, Caroline. “The Spanish Princess is Not 100% Historically Accurate, But That’s Not the Point.” Town & Country, 2 November 2020, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/arts-and-culturea/a34348047/is-spanish-princess-true-historically-accurate/

Larrechi, Aloña Fernandez. “El despróposito histórico que solo sirve para indignarse,” Serielizados, June 2019, https://serielizados.com/the-spanish-princess-el-desproposito-historico-que-solo-sirve-para-indignarse/.

Lenker, Maureen Lee. “The Spanish Princess creators on the series finale and giving Catherine a proper send-off,” Entertainment Weekly, 29 November 2020, https://ew.com/tv/the-spanish-princess-creators-break-down-series-finale/

Parker, Alexander. The Mind and Art of Calderón (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988): Parker 348).

Quintero, María Cristina. “English Queens and the Body Politic in Calderón’s ‘La cisma de Inglaterra’ and Rivadeneira’s ‘Historia Eclesiastica del Scisma del Reino de Inglaterra,’” MLN 113, no. 2 (Mar. 1998): 259–282, esp. 265.

William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, “Henry VIII.” The Riverside Shakesepare, eds. J.J.M. Tobin and G. Blakemore Evans (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), 1026-1064.

Tremlett, Giles. 2011 biography foreignizes her by the appellation Catherine of Aragon: Henry’s Spanish Queen. London: Faber and Faber, 2011.

- Caroline Halleman, “The Spanish Princess is Not 100% Historically Accurate, But That’s Not the Point,” Town & Country, November 2, 2020, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/arts-and-culturea/a34348047/is-spanish-princess-true-historically-accurate/[↑]

- This ambivalence can partly be traced to print media’s treatments of the Tudor queen. For instance, the title for Giles Tremlett’s 2011 biography foreignizes her by the appellation Catherine of Aragon: Henry’s Spanish Queen.[↑]

- Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995), 9.[↑]

- Lee Bliss, “The Wheel of Fortune and the Maiden Phoenix of Shakespeare’s King Henry the Eight,” ELH 42, no. 1 (Spring 1975): 2–3.[↑]

- As there a considerable amount of scholarship focused on Shakespeare’s representation of Katherine in All Is True, I will mainly be focusing on Calderón and the Starz series The Spanish Princess.[↑]

- Glynne Wickham, “The Dramatic Structure of Shakespeare’s King Henry the Eighth: An Essay in Rehabiliation,” Proceedings of the British Academy 70 (1984): 149–66, esp. 165.[↑]

- Amy Appleford, “Shakespeare’s Katherine of Aragon: Last Medieval Queen, First Recusant Martyr,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 40, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 149–172, esp. 152.[↑]

- Appleford, “Shakespeare’s Katherine of Aragon,” 159.[↑]

- Emma Luisa Cahill Marrón, Arte y poder: negociaciones matrimoniales y festejos nupciales para el enlace entre Catalina Trastámara y Arturo Tudor (PhD dissertation, Universidad de Cantabria, 2012), 11.[↑]

- Barbara Fuchs, Exotic Nation: Maurophilia and the Construction of Early Modern Spain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 1-11.[↑]

- The Hollywood Reporter, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-reviews/spanish-princess-review-1207459/[↑]

- Appleford, “Shakespeare’s Katherine of Aragon,” 159.[↑]

- William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, King Henry VIII, ed. Gordon McMullan (London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2020), 4.1.44-45, 368.[↑]

- Aloña Fernandez Larrechi, “El despróposito histórico que solo sirve para indignarse,” Serielizados, June 2019, https://serielizados.com/the-spanish-princess-el-desproposito-historico-que-solo-sirve-para-indignarse/.[↑]

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca, La Cisma De Inglaterra, ed. Francisco Ruiz Ramón (Madrid: Editorial Castalia, 1981), II.1756–7, 145. All citations from La Cisma De Inglaterra will be taken from this edition.[↑]

- Barca, La Cisma De Inglaterra, III.2797–2799, 187.[↑]

- María Cristina Quintero, “English Queens and the Body Politic in Calderón’s ‘La cisma de Inglaterra’ and Rivadeneira’s ‘Historia Eclesiastica del Scisma del Reino de Inglaterra,’” MLN 113, no. 2 (Mar. 1998): 259–282, esp. 265.[↑]

- Barca, La Cisma De Inglaterra, I.450–456, 94.[↑]

- Barca, La cisma De Inglaterra, I.719–27, 104.[↑]

- Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995): 62–122.[↑]

- Alexander Parker, The Mind and Art of Calderón (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 348.[↑]

- Parker, The Mind and Art of Calderón, 26.[↑]

- Parker, The Mind and Art of Calderón, 26–33.[↑]

- Barca, La Cisma De Inglaterra, I.746–750, 104–5.[↑]

- Emma Luisa Cahill Marrón, Arte y poder, 11.[↑]

- Cahill Marrón, Arte y poder, 15.[↑]

- Barca, La cisma De Inglaterra, III.2794–2797, 187.[↑]

- Barca, La cisma De Inglaterra, I.783–798, 106.[↑]

- Barca, a Cisma De Inglaterra, III.2654–2661, 182.[↑]

- While historical sources confirm that Catherine indeed commanded the English military forces and gave a speech to boost the morale of her soldiers, she did not lead the vanguard of the forces.[↑]

- Halleman, Town & Country.[↑]

- Maureen Lee Lenker, “The Spanish Princess creators on the series finale and giving Catherine a proper send-off,” Entertainment Weekly, 29 November 2020, https://ew.com/tv/the-spanish-princess-creators-break-down-series-finale/[↑]