Martin Duberman

MMG: I want to start by asking your thoughts on what a queer left agenda must include.

MD: We’re talking about restructuring the whole society. We’re talking also about two hundred or so years of debate. I’ve gone back and forth in my own history between devotion to anarchist thought and socialist thought. Or you can always be an anarcho-syndicalist, which is probably the closest thing. In my younger days I would certainly have said I was that, though I don’t want to go back to the Diggers and get rid of all the technological improvements.

I’ve long argued, though, that there should be a fixed minimum income for everybody. At one point, I was saying 25,000 dollars per year. Now it would have to be higher. The reaction has always been outrage, “What! For people doing nothing at all you would just give them 30,000 a year?” And my answer has always been, “Yes, because they will then do something.” Human beings are innately inventive and creative. Most people simply lack the time and opportunities to indulge or explore any of that side of themselves. So god knows what they would do if freed up a bit. But they’re not going to just sit on the couch and stare at the wall. In the meantime, people wouldn’t have to suffer all those anxieties—“Will I be able to put food on the table?” I would also put a cap on how much an individual could make. I have no idea what I would put. But everybody would also get free education, free college and graduate school, free health care. I think all this is obvious. Basically, I don’t believe that an economic incentive is the absolute incentive. I think the creative incentive would surface soon enough if people weren’t so constantly worried about material things.

I think of it more in terms of what all Americans need rather than just LGBT people. I think what we suffer most from is the atomization of everyday life, which is true of so many people regardless of their sexual orientation. It used to be that people were isolated in suburbia. Now it doesn’t matter even if you are living in the heart of Manhattan. Because work is so repetitive, boring, and draining, people just want to be alone when they get home. We need to change the nature of work itself.

I think the capacity for intimacy, for friendship, is lost. Not entirely, but so much of social life is made up of superficial, glancing connections in which you exchange surface information about what your activities have been since you last saw each other. The actual exchange, the deep feelings, the deep issues are neglected. Go to a hospital and see how many people get no visitors. And these are heterosexual people who are married and have families, but nobody has any time if the patient happens to be over 65 or 70. Or they drop in for ten minutes. Walk down the street and you see all these people attached to their gadgets. They’re talking on their cell phones and listening to their iPods. They’re oblivious of their surroundings, and that includes other human beings. They’re these isolated boxes of sound that are moving down the street.

I’m not sure it’s finally easier to write books, or easier to write good books, with all this technology. In the old days when I did interviews, I took notes. The person and I were constantly interacting, just getting impressions of each other visually. You couldn’t rely on all this machinery; you had to rely on your own senses, on what you were picking up. Is this person a reliable witness? Is this person as wacky as I initially thought? We started to talk. You had to connect. You could be wrong in whatever impressions you came away with, but at least you came away with earned impressions of who the other person was. Here all you got are the remnants, the voice. I think voices are very deceptive.

MMG: So, intimacy. That would be on your new queer agenda?

MD: I think that follows from almost everything else. You can’t create intimacy. You have to create the kind of environment where human contact flourishes. If you look around at the humans that we are producing these days, in this society, I think we are a more adolescent culture than most. We don’t have many adults wandering around the United States. We have a lot of outsized children. You would have to change so much in order to produce a different kind of person that it’s very close to unthinkable. Earlier, during the 1960s, a lot of us didn’t think it was unthinkable at all, because the technological world hadn’t settled in to the degree it currently has. It’s not like I don’t admire some of the features of the new culture, but we now have people sitting in a railroad car talking at the top of their lungs on their cell phone as if they’re the only creatures on the planet. It’s like they’re almost unaware of what level you need to address another human being because they’re basically spending their lives talking into machines of one kind or another.

Everything we’re talking about relates to being alive on the planet today, and has very little to do with sexual orientation. In terms of LGBT issues, every time I see a public opinion poll it’s the 18-25 year-old group that gives grounds for hope. That’s the group that favors gay and lesbian marriage by the biggest margin. The higher you go in the age brackets, the less approval there is. So I find hope that the upcoming generation seems more progressive in its politics than any that has recently preceded it. Some of this is due, I think, to the fact that more and more people are coming out and being seen. There’s a growing awareness that the LGBT communities in fact represent a far wider group of human beings than the standard stereotypes that existed 50 years ago. The movement deserves some credit for this.

But the movement down to the present day has not been that welcoming to people of color. All kinds of subtle racism are omnipresent still. Not just in the gay communities; racism is everywhere. And sometimes I wonder why we are all saying LGBT when an awful lot of Gs and Ls can’t stand transgender people or think they’re sick, just as the general population does. Bisexuals in our G and L communities seem to be invisible, yet books are coming out by bisexual people. This fictional unity of putting these four letters together doesn’t make for a true understanding among the different communities that make up the queer world.

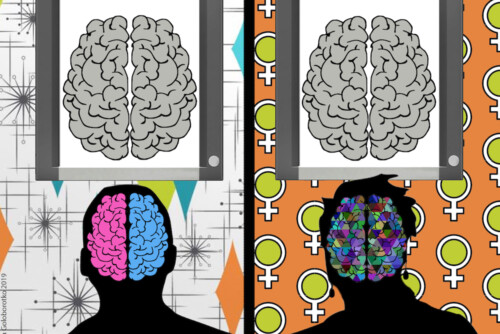

And now with queer theory, nobody is just gay or just straight. We’re all a wild mix. Just pay attention to your dreams and you’ll see how available we all are for all kinds of activity, and individuals. Though right now I think the binary is powerfully strong. I think it’s very puzzling. It’s very hard to grapple with because, on the one hand, those of us who are lefties want to claim we’re not “just folks:” we have a different historical experience and therefore a different perspective, a different set of values. But, on the other hand, we want to be making the argument that everybody is queer. Nobody is gay or straight. We’re all this wild bundle and mix of fantasies and possibilities and that’s what we have to explore. Saying the most important thing about you is that you’re gay or you’re lesbian puts you in a little box and prevents you from looking at any other aspects of who you are.

With decades of progressive activism between them, both Achebe Powell and Martin Duberman exemplify progressive queer thinking and organizing in the latter part of the twentieth century and the first years of the twenty-first. Their individual perspectives are grounded in their personal experiences of oppression as well as privilege, and they both insist on wide-ranging, even ecumenical, analyses of social justice that go well beyond questions of sexuality and gender. They offer us valuable historical perspectives while helping us imagine and create a new queer agenda for the future.