Connie Samaras’ Minimalist Aesthetics in V.A.L.I.S.

Though the context of Antarctica is different (it is the only place in the world without an indigenous population), both Isaac Julien and Connie Samaras are challenging our perceptions of these regions as well as our devotion to the older heroic narratives. In the case of Samaras, who traveled to Antarctica and the South Pole with a National Science Foundation grant in 2004-5, her work also responds to a number of other issues specific to Antarctica now, such as: the enormous, continuously accelerating increase in tourism to Antarctica in the past decade; the impact of global warming; the soaring prices of raw materials, which strain agreements governing the status of the polar region;, and the consequences of the 1959 treaty, which protects the continent for big science and allows countries like the U.S. to build outposts there. She is engaging a history of visual representation of Antarctica and the way this region is still imagined as an empty frozen wasteland of snow and ice reminiscent of earlier imperial narratives of Arctic and Antarctic exploration long after the Heroic Age of exploration has passed. 1

Samaras’ V.A.L.I.S. (vast active living intelligence system) consists of photographs and two videos she took while on an artist’s residency. She approaches Antarctica from a feminist perspective, deliberately anti-heroic in its focus on what it means to live in such an inhospitable, and thus anxiety-provoking, built environment. As Samaras puts it, “because the Antarctica imaginary is strong (perhaps because so few have traveled there), I attempted to show the ice as a place, like any place, where the exotic can be disclosed in the everyday.” 2

Buried Fifties Station

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

Her aesthetics of the everyday plays out very differently than does Isaac Julien’s work, which is more about returning us to an earlier heroic era and the epic. If Julien creates a new aesthetic by out-subliming the sublime, Samaras goes in the opposite direction and creates a minimalist aesthetic that matches the minimalism of a hostile and uncaring environment (see Figure 7). Significantly, her aesthetic is located in the context of a post-heroic age. Moreover, paralleling these aesthetic differences is Samaras’ emphasis on the contemporary everyday, while Julien seeks to return to the heroic registers of the early 20th century to ironically re-invent them. Thus, Samaras’ visual project is framed explicitly as post-heroic and intervenes in the discourse that confidently explores, maps and visualizes a space, thus turning it into a place we now claim to consume. In questioning these discourses, Samaras’ post-heroic aesthetic is deliberately at odds with hegemonic tourism narratives and photographs.

Amundsen-Scott Station Phase III (triptych)

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

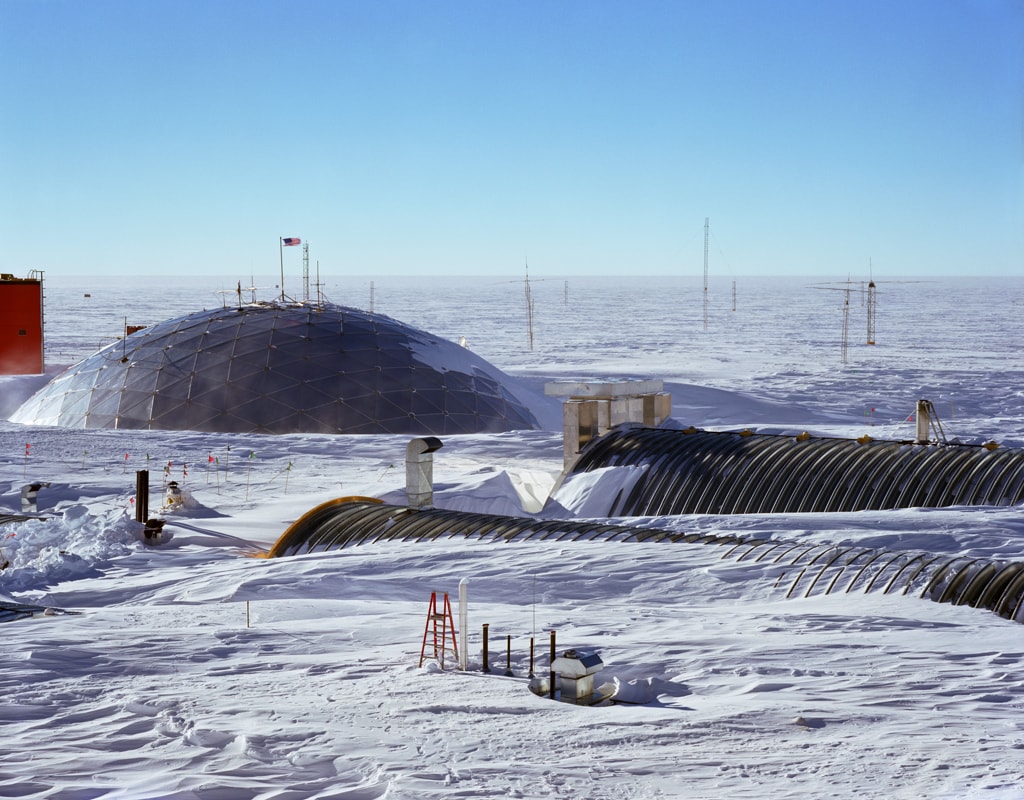

Her project is founded in another genre altogether—science fiction and horror, which interest her in part for their critique of technology and also the way both genres create anxiety to make us question what we see and know. Her aesthetic approach to Antarctica makes us interrogate the gap between what we expect to see—touristic views of nowhere that represent the landscape as pristine and empty—versus her image of Antarctica as a somewhat flat corporate environment, not quite a rooted place but more of an eerie transit zone in an extreme environment (see Figure 8). 3 This makes her work more in dialogue with the present discursive context of Antarctica and how these sites are no longer understood simply as remote spaces that demand to be mapped, but rather as spaces closely connected to globalized economic and geo-political forces. Her work on Antarctica attempts to symbolically position Antarctica in the neo-liberal order, which is fitting as one of the buildings she photographs is owned by Raytheon, a leading company in the weapons industry. One of the consequences of neo-liberalism is to render a certain degree of uniformity to all cities. Obviously that isn’t quite possible in Antarctica because of its extreme climate, but the built environment suggests a kind of neo-liberal logic emerging as evidenced by her photograph of the submerged Buckminster Fuller dome that make it appear as if it has been abandoned or left to deteriorate, not because it cannot be used meaningfully, but perhaps because it cannot be used profitably (see Figure 9). Samaras herself has written on neo-liberalism and why these images of Antarctica belong in a larger series that includes photographs of the built environments in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas, amongst other sites. 4

Dome and Tunnels

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

Still, there is a uniqueness to her images that make them particular to the minimalist aesthetics of the Antarctic landscape. The otherworldly and corporate aspect of her images has to do in part with the emptiness of the space and the way she makes many of her structures look like buildings in the middle of nowhere, unable to make a dent in the earth. Like the landscape, her interiors are empty and deserted. 5 Her focus on these alien-looking buildings, combined with her emphasis on the un-domestic interiors and exteriors, such as her triptych of the new Amundsen-Scott Station under construction (see Figure 10), have a strangeness that is intermixed with their ordinariness, creating a dissonance with, on the one hand, the discourse of Antarctica as an untouched landscape and, on the other, a scientific utopia of the future. The ordinariness also has to do with the way buildings such as the new Amundsen-Scott station, built by a Hawaiian architect and construction company for Raytheon, looks like the buildings of other neo-liberal environments with which we are all familiar, and constructed by similar companies elsewhere in the world.

Detail (Panel 2), Amundsen-Scott Station Phase III (triptych)

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

- For a more sustained discussion on the history of Antarctic photography see: Elena Glasberg’s “Blankness in the Antarctic Landscape of An-My Lê” in this special issue, as well as “Camera Artists: Gender in Antarctic Visual Culture.” New Zealand Journal of Photography. Special Feature on Antarctic Representation (2007).[↑]

- Cited in Samaras’ article in this special issue titled, “America Dreams.”[↑]

- For other reviews of Samaras’ Antarctic photographs, see the following: Kristina Newhouse, “Connie Samaras: V.A.L.I.S..” X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly. 10:4 (2008); Matais Viegener, “Connie Samaras, De Soto Gallery, Los Angeles CA.” Artus (Fall 2007).[↑]

- See Samaras’ article in this special issue titled, “America Dreams.” The production of her series of photographs and videos on Dubai currently titled “After the American Century,” begun in late 2008, will deal with speculative landscapes, architecture and geopolitical narratives, political geographies in the everyday and differing science fictional tropes of imagining the future.[↑]

- The solo premiere of Samaras’ body of work on Antarctica in the U.S. took place at the De Soto gallery in Los Angeles in October of 2007. It also appeared in a group show on Antarctica at the Pitzer Campus Gallery in Clairmont, CA in November 2007-January 2008, curated by Ciara Ennis.[↑]