The Plasmodium Parasite

Malaria (from the French for “bad air”) is a catachrestically named syndrome characterized by lethargy, fever, delirium, and sometimes death in humans that manifests an “infection” by parasitic microorganisms or, put more precisely, the human host’s becoming incapacitated by the reproductive robustness of the Plasmodium Protista (Protista refer to the kingdom of single-cell, nucleus-bearing organisms formerly called Protozoa). Malarial fevers correspond to the erythrocytic (or red-blood cell) stage of Plasmodia’s reproductive cycle as its merozoites multiple exponentially in the blood stream via schizogony (a kind of explosive mitotic division). To put it more starkly, though we think of malaria as a disease linked to human morbidity and thus the antithesis of reproductive vitality, malaria is also a disease of insect and protozoan reproduction. 22

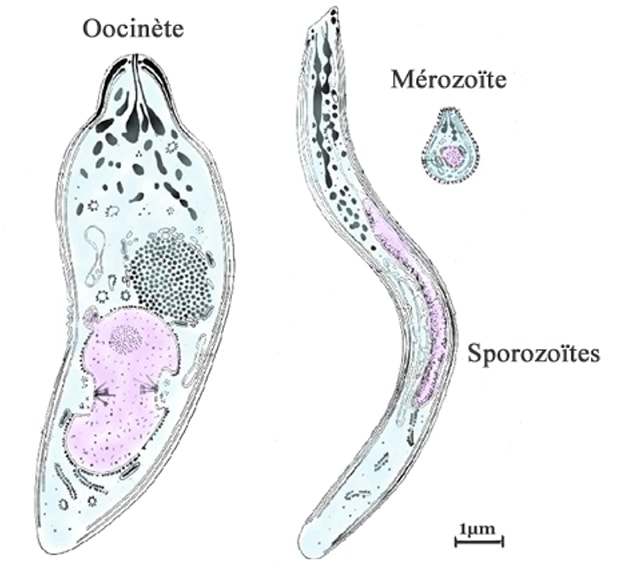

Plasmodia are unicellular, eukaryotic (nucleus bearing) organisms that predominantly live inside other cells, i.e., they are “intracellular.” 23 However, when transiting from one milieu to another—e.g., from mosquito gut to vertebrate liver cells—Plasmodia take on an “extracelluar” form “specifically designed to find, recognize and enter a specific host cell.” 24 These extracellular morphologies, all characterized by an apical complex, are further distinguished into three types: sporozoite, tailored to the liver cell; merozoite, tailored to the red blood cell; and ookinete, tailored to squeezing in between mosquito gut epithelial cells (see Figure 1, below).

This “polymorphism” according to Christophe Rogier and Marcel Hommel, comprises an “important survival strategy in Plasmodium,” and it has a characterological corollary in Ghosh’s novel—Mangala’s research team, Murugan speculates, has found a way to transport themselves across different bodies (and thus different times). 25 Thus, if Mangala is the life form (akin to Plasmodium), the sporozoite, merozoite, and ookinete phases of her correspond to Mrs. Aratounian, Urmila, and Tara (the same being true for Laakhan and the phases Ronen Haldar/Lutchman/Lucky). To speak of this horizontal personality transfer perfected by Mangala’s group as reincarnation or body jumping colors this technology with the aura of the fantastical or counterfactual. But through his evocation of the malaria “bug,” Ghosh makes legible the polymorphisms of his main characters through Western science, e.g., microbiology, as he also emphasizes correspondences amongst scientific and mystical (spiritualist) theologies; it is microbiology that connects sporozoite to merozoite to ookinete, seeing them not as separate, disconnected entities but rather as stages of a mutating nucleic and cytoplasmic choreography. 26 In parallel fashion, by the end of Ghosh’s novel, separate characters inhabiting different spaces and historical time periods—e.g., the dust sweeper, Mangala, of unknown origins employed in Ronald Ross’s malaria research lab in Calcutta circa 1898; the journalist Urmila Roy living in Calcutta circa 1995; and the Armenian hostel proprietor, Mrs. Aratounian, also living in Calcutta circa 1995 are implied as various phases of a single biological entity who in the narrative present appears as Tara, the undocumented nanny living in New York in the late-twentieth to early-twenty-first centuries.

The multiple embodiments (stages) of Plasmodium provide a template for comprehending human migration, colonialism, and encounters between hosts—relatively “static” and large-scale bodies, compared to the organisms inhabiting them—and guests, motile or traveling microontologies. In one major tradition of the philosophy of ethics, hosting work turns on the alienness (rather than the scalar disjunctiveness) of the guests vis-à-vis their hosts, with the limits of ethics contemplated via the hosts’ capacity for unconditional hospitality—to entertain the strange and even violating customs proposed by guests, for instance, that the hosts’ daughters be served up to the guests for sexual violation. 27 Hosting—as I am using it here—raises the issues of the entanglement of the natal and the alien, and the unclear, involuted spatial boundaries that perplex us when thinking about the Plasmodium’s intra- and extra-cellular forms. That is, even Plasmodium’s “extracellular” forms (fig. 1), in which it shuttles from one milieu to the next, remain “in bodies”—that is, bathed in the fluids of a host’s tissues—an observation adding complexity to the firm border between inside and outside bodies. Plasmodium’s life cycle reminds us that while from the microorganismal perspective, there is indeed a milieu—e.g., the bloodstream of the vertebrate, the gut of the mosquito—seemingly outside the extracellular form of Plasmodium bodies (these are their infrastructures of reproduction, to use Murphy’s terms), from the host species’ perspective, that outside is also embodied or “in body” (the cosmos becomes also an inside, so to speak). The point to be registered regarding this changed perspective is not that there is no outside the body, but rather that, through a transformed ethico-epistemological “touch and regard” for Plasmodium—as opposed to an infectious disease approach to malaria—we become attuned to the entangled web of interspecies dependencies. 28

In her work on companion species, Donna Haraway uses the etymological root of companion—cum panis (with bread, eating well together)—to characterize the texture of human-canine relationality she, at other times, calls “touch and regard”—a mutual learning and caretaking that is intimately proximate (touches) but still remains separable and at some distance (regard which involves esteemed “looking”—with sight, as opposed to touch, historicized as a distancing sense): “Messmates at table are companions. Comrades are political companions. A companion in literary contexts is a […] handbook [to] help readers consume well.” 29 Playing with the semiotic slippage of companion, Haraway expressly includes symbiogenesis and “potent transfections” between species divides as that toward which an orientation toward companion species makes us less anxious. 30 Ghosh’s novel proposes such potent transfection in vertebrates’ existing reproductive integration into Plasmodium’s lifecycle and hypothesizes humans’ eventual reliance upon Plasmodium to reproduce themselves parasexually (the technique that Mangala’s group refines). Yet the scalar disproportion of humans and Plasmodium makes mostly illegible their possible cum panis (eating with, instead of feeding upon) relationality. Instead of a companion relationality, then, we might speak of Ghosh’s novel installing a “touch and regard” for the entangled web of interspecies dependencies—what I call a chimeracological embeddedness or onto-epistemology.

My neologism, chimeracological, is formed through the merging of the terms chimera, derived from the ancient Greek, Khimaira, referring to a hybrid monster composed of several different animal parts, 31 and ecological, a secular subset of the cosmological. Chimeras have become a humdrum reality of the laboratory, which we know by way of bioreactors—the modification of animals to produce human hormones—and the use of bioluminescence derived from fireflies and sea pansies and introjected into mammalian tissues in medical imaging, for instance. My usage of the term refers not simply to these instrumental uses of animals in the medical and pharmaceutical industries of the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries, but the more longstanding entanglements of species intuited by that ancient term, which biogeneticists have, in the last forty-five years, confirmed underlie complex organism’s thriving and evolution. According to Haraway, developmental biologist Scott Gilbert stresses that “nothing makes itself in the biological world, but rather reciprocal induction within and between always-in-process critters ramifies through space and time on both large and small scales in cascades of inter- and intra-action.” In embryology, Gilbert calls this “interspecies epigenesis.” 32

A feminist ecological project might associate the chimeracological with the females of the human species due to either their biological capacities of gestating alterity or their cultural histories of nurturing other life. The proposition made by object-relations and materialist standpoint variants of American feminism in the late 1970s and early 1980s, that “women’s relationally defined existence, bodily experience of boundary challenges, and […] experience [of] others and themselves along a continuum” derives materially from women’s gestational labor, need only a slight modification to figure as a standard-bearer for the chimericalogical: “the child [aka uterine guest or parasite] carried for nine months can be defined ‘neither as me or as not-me,’ [with] inner and outer … not polar opposite but a continuum.” 33 Accused of essentialism, this vein of feminism remains distinctly out of fashion; yet we might consider aspects of it anew given its harmonizing with microbiologists’ calling into question the virtue and reality of species’ and organismal autonomy, which is to say “the self experienced as walled city […] discontinuous with others.” 34 While a feminist object-relations approach looks to women’s reproductive labor as seeding a possible greater comfort with the lively continuum of interspecies epigenesis, the microbiologists’ rejection of organismal autonomy (and prizing of entanglement as a condition of health, life, and existence) sees that insight or comfort as a function of viewing the world at the scale of the microbe.

Even as I do not endorse the notion of a feminine disposition especially attuned to hosting the alien, whether historically or biologically patterned, I propose here a queerness in the hyperbolic heteroness of Plasmodia’s seeding grounds. We might regard the Plasmodium’s reproductive technique as both queer (nonheteronormative) and hyperbolically hetero—the latter alluding not to object choice or the requirement of haploid “male” and “female” gametocytes that subsequently fuse—but hetero in terms of the distributed, epigenetic seeding grounds, as it were, of its multistaged schizogony: the multiple migration of the Plasmodium from the intestinal wall of the mosquito to its salivary glands to the liver and the red blood cells of the vertebrate. The Plasmodium’s morphologies and kinetic processes require hosting milieu comprised of other animal bodyparts akin to the polluted waterways Murphy dubs infrastructures of reproduction.

By framing the novel as offering a portrait of queer reproduction, one that prompts a rethinking of normative heterosexual reproduction—i.e., “between a man and a woman”—as at the core of the future continuance of an elect species-being, my point is not that the narrative centers gay/lesbian desire. Rather, Ghosh’s novel, read through a microbiologically informed lens, limns the entangled reproductive cycles of several species. Mangala’s group in Ghosh’s novel, in other words, treats not as pathological, but as natural and even as advantageous, entanglement in another’s alter-reproductive habits (whether gay or “schizogonic”—a neologism drawn from the fissioning of protist sporozoites in the bloodstream of vertebrates). Here, I suggest a productive contagion between a microbiological-animal studies and femiqueer approach, especially in their shared political ethics toward reaffirming intimate entanglement with other social and biological life, not as something to be feared (that which induces panic), but as part of the vis medicatrix naturae. 35

According to Ed Cohen, our current notions of biological “immunity” began as a political metaphor, i.e., the state of being disobliged from others, freed from responsibilities to the munis or political collective, and it is only in modernity that this political idea migrates into the spheres of science and medicine, and is described as an innate capacity of an organism’s biology. These forgotten political origins are partly responsible for our construing as “natural” the idea of an atomistic cell (or individual) at war with each and every other. What this view of the defensive body forgets, according to Cohen, is a prior view of the vis medicatrix naturae, the healing power of nature: “According to this worldview, healing manifests the organism’s natural elasticity: it incorporates the organism’s most expansive relations to the world, embracing the forces that animate the cosmos as a whole.” 36 Citing the microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Cohen’s critical biopolitical studies approach suggests the need for a politics attuned to how “organisms evolve not just by competition and ‘survival of the fittest’ but also by cooperation and symbiosis [Margulis claims] that all nucleated cells represent the successful fusion of two or more bacterial lineages [aka chimeras] ‘The human body is an architectonic compilation of millions of agencies of chimerical cells.’” 37 Speaking to humans’ cooperative entanglement with bacterial cultures, Heather Paxson coins the term post-Pasteurian to refer to a (re)new(ed) regard for bacteria and other microorganisms as also symbiotic actors alongside humans, rather than “anthropocentric[ally] evaluat[ing] such agents” as carriers of disease. 38 To what extent can these compilations of chimerical cells offer a model of cross-species, cross-populational intimacy that forms an alternative to, but not a mere apology for imperial-colonized relations?

- The female mosquito’s reproductive robustness too depends on the vertebrate, “blood being a necessary requirement at different stages in the life cycle of a female mosquito [such as] ovarian development and egg laying.” See Christophe Rogier and Marcel Hommel, “Impact Malaria,” http://en.impact-malaria.com/iml/cx/en/layout.jsp?scat=746866F9-2FEE-4C5E-9770-A544EE462C14.[↑]

- Rogier and Hommel, “Impact Malaria.”[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- “The polymorphism of Plasmodium populations is considerable and it has been evaluated that, on average, a malarial infection in humans represents 3.9 parasite populations.” Rogier and Hommel, “Impact Malaria,” http://en.impact-malaria.com/iml/cx/en/layout.jsp?cnt=22EECA67-FA09-42BD-8748-FA5ED64476AE.[↑]

- Ghosh 2001[1995]: 251.[↑]

- Rosalyn Diprose, “Women’s Bodies Between National Hospitality and Domestic Biopolitics,” Paragraph 32.1 (2009): 69-86; Jacques Derrida, “Hospitality,” trans. Barry Stocker and Forbes Morlock, Angelaki 5.3 (2000): 3-18.[↑]

- Donna Haraway, When Species Meet, (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2007).[↑]

- Haraway 2007: 17.[↑]

- Haraway 2007: 15.[↑]

- Gk. khimaira, a fabulous monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail.[↑]

- Quoted in Haraway 2007: 32.[↑]

- Adrienne Rich cited in Nancy Hartsock, “The Feminist Standpoint,” Discovering Reality: Feminist Perspectives on Epistemology, Metaphysics, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science, eds. Sandra Harding and Merill B. Hinnitikka. (New York: Kluwer Academic, 1983): 229.[↑]

- Hartsock 1983: 230.[↑]

- Ed Cohen, A Body Worth Defending: Immunity, Biopolitics, and the Apotheosis of the Modern Body, (Durham: Duke UP, 2009).[↑]

- Cohen 2009: 4.[↑]

- Cohen 2009: 72-3.[↑]

- Heather Paxson, “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States.” Cultural Anthropology 23.1 (2008): 15-47.[↑]