Editors’ note: Barnard alumna Meryleen Mena 1 is the sole contributor to this issue who did not speak at Invisible No More in November 2017. We accepted this unsolicited submission following the March 2018 assassination of Black Brazilian Lesbian feminist organizer and Rio de Janeiro city councilmember Marielle Franco, which has since been tied to members of the military police, in the hopes of offering broader context to both the subject matter of this issue and to Franco’s murder, and of making critical connections between patterns and drivers of police violence against Black women in the United States and internationally.

Why does the “negra empoderada [empowered Black woman] offend so much?” 2 Black feminists in Brazil and in the diaspora have wrestled with variations of this question for some time. In March 2018, it resurfaced in the wake of the assassination of Rio de Janeiro City councilmember Marielle Franco, a Black 3 working-class lesbian. It is an inquiry that reveals the lingering postcolonial anxieties that shape Brazilian society and one that incisively rejects the fantasy of a racial democracy. 4 Why are Black women constantly policed by the state and by fellow Brazilians? 5 Black Brazilian feminists 6 pose this question to the powerful white and light-skinned mestiço (mixed-race) minority who serve as the gatekeepers of national culture and dictate the parameters of normalcy and what constitutes Brazilian identity. I read the inquiry of why Black women’s bodies offend as a desperate cry from the depths of the mourning Black body. Black women’s impetus to speak out against the state terror and atrocities that target their communities is a response to the specific ways in which their bodies have historically been and continue to be policed, and the silence that their criminalization, incarceration, and death engenders.

In this article, I argue that, whether empowered – broadly defined – or disenfranchised, Black women’s bodies are perceived to offend and as a result are subjected to different forms of racialized and sexualized violence, including everyday violence (e.g., domestic abuse) and state violence (e.g., police abuse while in custody). In support of this position, I offer three examples of how the Brazilian state enacts violence against Black women. First, I examine the death of Marielle Franco and its sociopolitical aftermath, an event that was both spectacular and mundane and that has mobilized Black women to further advance social and political projects on behalf of the communities that Brazil’s white supremacist state attempts to obliterate. I then consider the policing and detention of two young Black women in São Paulo: Verônica Bolina, a transgender woman who remains in a pretrial detention center for men as of the time of writing, and Andreza Delgado, a gender nonconforming woman who was violently apprehended and then released. To conclude, I examine how each of their experiences further illuminates the question posed by Black feminists – Por que a mulher negra empoderada incomoda tanto? (why does the empowered Black woman offend so much?) – and shapes Black feminist resistance.

The Death of a Black Politician: Marielle Franco

On the morning of 15 March 2018, I awoke to the shocking news that Rio de Janeiro councilmember Marielle Franco, representing the Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (Socialism and liberty party; PSOL), had been killed, along with her driver Anderson Pedro Gomes, in a drive-by shooting. She had only been in office for two months. 7 As the days went by and more details emerged regarding possible suspects, rumors that suggested police involvement began to circulate. Marielle had been followed closely and the assassins knew exactly where she was sitting in the vehicle when they pulled up in a car and opened fire. No cash, documents, or cell phones were stolen. 8 The evidence at the scene of the crime was mishandled and Marielle and Anderson’s bodies were not properly examined. 9 Still, officials claimed that the murders were just another incident of urban crime.

Nearly a year to the day after Marielle’s and Anderson’s deaths, two white men with ties to the police and to the recently elected far right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro were arrested for the murders: former police sergeant Ronnie Lessa and former military police officer Élcio Vieira Queiroz, who in 2011 had been expelled from the force. Police arrested Lessa, who is believed to have fired the shots, from his apartment in the same luxury condominium where President Bolsonaro and his family live. The two families are known associates, and one of Bolsonaro’s sons dated Lessa’s daughter. The culprits allegedly began to plan Marielle’s death weeks before she took her oath of office in January 2018.

While from the very beginning there were few doubts among Marielle’s supporters as to why she was targeted, what remains a mystery is who gave the orders. One of the strategies that Brazil’s Black movement uses to demand justice on behalf of people killed by the state, especially when police murders gain media attention, is to ask, Who killed so-and-so? Since Lessa’s and Queiroz’s arrests in March 2019, the query has become, “Quem mandou matar Marielle?” (Who ordered Marielle’s killing?), implying that this case is far from over despite the arrest of two known perpetrators. Identifying who ordered the hit – and why – might ultimately help us to better understand the state mechanisms that routinely police and kill Black people, and increasingly Black women, despite the social and political advancement of working-class Brazilians in the last two decades. 10

Why Marielle Franco?

Societies built on deep-rooted racial stratification, like Brazil, are threatened by upwardly mobile people of color. If these individuals call out corruption and violence, and if they work to pull others from the hopeless living conditions that structural violence creates, their actions, in addition to their existence, unsettle the status quo. Marielle was a rising political star, and the intersections of her social identities, as well as her politics, were offensive to many. She both was an empowered Black woman and was legally attempting to dismantle what scholars call the state’s anti-Black genocidal project. 11

The night of her murder, Marielle was on her way home after a spirited roundtable discussion at Casa das Pretas (Black Women’s House), an activist collective. The evening’s conversation focused on empowering young Black women in Rio de Janeiro – a state where the prospects for a life with dignity and wellbeing for Black people, and Black women in particular, are few and far in between. 12 She closed her talk by citing Audre Lorde: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. And I am not free as long as one person of Color remains chained. Nor is any one of you.” 13 In addition to living Lorde’s words through her activism and her political leadership, Marielle, like Lorde, embodied an African aesthetic in a society that values African culture but not people of African descent. Her commitment to Black women’s empowerment and refusal of anti-Blackness made her a threat in a society premised on the latter and denial of the former.

In some ways, Marielle was the poster child for the white neoliberal capitalist fantasy that claims that if one works hard one can achieve anything – a notion that resonates beyond Brazil. She grew up in Maré, one of Rio de Janeiro’s poorest favelas, where through hard work, sacrifice, and communal support she pursued an education and continued to give back to and fight for her communities. She held posts in commissions for human rights and then became a councilmember to represent LGBT, Black, and working-class people. Yet her murder poignantly demonstrates that whether an “upright citizen” or a “bandida” (criminal woman), Black women’s lives are inherently disposable, particularly in a context such as Brazil where their bodies are nearly synonymous with hard labor and domestic work. For conservatives, Marielle’s dissident body did not belong among other law makers. If there was a place for her in Brazil, it would be in her traditional social position where she is quiet and servicing the needs of white elites. Daring to interrupt the social and political boundaries that confine Black women to their historical roles as caretakers always comes at a high price. Marielle was violently stopped in her tracks precisely because she was slowly gaining power and recognition from a wide range of marginalized groups as well as from more mainstream constituents, while attempting to enact structural changes in how the police punish Black and other poor populations of Rio de Janeiro. In other words, Marielle was a menace to a society built on white supremacy. 14 It was not only Marielle who was attacked that evening; symbolically and literally, it was also the struggle for a more inclusive and representative politics. Marielle’s appeal and her assassination were a product of her and her communities’ resistance and rejection of the police violence that overshadows life for impoverished populations throughout Brazil.

Brazil is notorious for its trigger-happy military police who frequently target Black and low-income communities in urban settings such as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and São Paulo. In Brazil, the police are divided into two main branches. Military police typically have no direct ties with the military in spite of their name, but rather are uniformed members of law enforcement who patrol the streets and function as militarized first responders. Civil police are plain-clothed officers who carry out detective, forensics, and other criminal investigation activities after people have been arrested. 15 In Rio de Janeiro, esquadrão da morte (death squads) carry out extralegal killings that target anyone from sleeping street children to people accused of petty crimes (theft, illegal drug use, and drug sale) to political activists. 16 When military police are killed, death squads are known to engage in “revenge killings,” terror campaigns in the favelas where people are disappeared, murdered, and mutilated regardless of whether they were involved in any criminalized activity. 17 They target Black populations who already struggle with the effects of police brutality and everyday violence. 18 Typically composed of off-duty police officers, death squads often collude with city officials, police chiefs, or other government personnel to carry out crimes, and do so with impunity: death squad murders are rarely investigated or prosecuted. Though Marielle’s was a politically motivated death, it was also remarkably mundane in the context of how police-led crimes shape the everyday violence favela residents experience.

Marielle spoke out against government inaction in response to everyday violence, as well as its role in extrajudicial violence in Rio’s favelas. As a councilmember, she advocated for Black lives and denounced the military campaigns ordered by the illegitimate 19 president of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, Michele Temer, that left scores of favela youth dead. 20 In February 2018, Temer ordered the Brazilian military to take control of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, taking charge of the military police under the pretext of cracking down on gang-related crimes and drug trafficking. 21 The results of this operation were catastrophic, with daily reports of police murders of favela residents – those linked to criminalized economies and those caught in the crossfire. 22 Marielle was part of a special commission that was investigating this federal operation, which she considered evidence of the state’s disregard for Black lives. The fact that she was closely surveilled by men linked to a right-wing state and killed in the aftermath of decrying excessive police force is therefore not surprising. Since 2014, twenty-four political officials have been assassinated in Brazil for uncovering injustices largely affecting marginalized groups. 23

Marielle’s friends and fellow activists hoped that her death would serve as a turning point in shifting this macabre reality. Marielle’s assassination marked 2018 as a year of political and social upheaval in Brazil, as thousands took to the streets in Brazil and internationally to publicly mourn her death, to denounce police violence, and to demand justice, chanting “Marielle Vive! Marielle Presente!” (Marielle lives! Marielle is here!), a testament to the effect Marielle’s political work had on the communities for whom she fought in Brazil and throughout Latin America. The October elections were historic in that an unprecedented number of Black women ran and won seats in public office, including São Paulo’s first openly transgender woman elected official, Érica Malunguinho. 24 Yet, once again invoking the question of why empowered Black woman offend, extreme-right former army captain, Jair Bolsonaro, who openly extolled Brazil’s last military dictatorship (1964 to 1985) as a victory, won the presidency by 55 per cent of the vote on an anti-female, anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, anti-LGBT, pro-military, and pro-gun platform.

Policing of Black Women in São Paulo, Brazil

I am a Black Dominican New Yorker and a cultural anthropologist who examined the experience of incarcerated women in São Paulo, Brazil, where I conducted dissertation fieldwork from February 2015 to March 2017. When I first arrived, I was set on studying the activism of Black mothers publicly mourning the police murders of their young adult children. Conversations with a Black legal scholar and a Black public defender, however, led me to redirect my focus to the other forms of state violence that were not quite as visible to the public, but which were nevertheless equally harmful to the Black populations of São Paulo – harms experienced within the criminal justice system. Beginning in April 2015, I sat in on pretrial custody hearings, a then recently implemented program in São Paulo’s criminal courts, and in August of that year, along with a prisoners’ rights nongovernmental organizationn, I started to visit women and gender nonconforming people incarcerated in four female penitentiaries. Though women and gender nonconforming people in Brazil are the fastest growing population of prisoners, scholarly and public attention to their policing and incarceration are relatively new. 25

It did not take long for me to learn the usual profile of the detained: uneducated dark-skinned Black working-class women with alleged involvement in the illegal drug trade. Similar to women incarcerated in the United States, many are survivors of domestic and intimate-partner violence. An overwhelming majority are heads of households who in one way or another got involved in the world of crime to help make ends meet, mainly as low-scale drug traffickers. Others were arrested and serving time due to their association with male partners involved in drug trafficking. In the wake of the 2006 drug laws in Brazil, inspired by our own Rockefeller drug laws, police had begun to aggressively target and arrest dark-skinned women. 26 Black Brazilian women have historically been stereotyped as sexual deviants and criminals, and their incarceration is a double punishment: a penalty for committing crimes, and a penalty for doing so as women.

While Marielle’s murder captured national and international attention, the terror and death that Black people experience at the hands of the military police and death squads are remarkably ordinary in Brazil. As anthropologists Jaime Amparo Alves and João Costa Vargas observe, “state violence against blacks is hardly a new phenomenon, as the rule of law has never been applied to protect black bodies.” 27 In general, police violence takes the form of policing and incarcerating urban poor and working-class people, physical and psychological torture during arrests, mass incarceration, and murdering young Black people. Death squads linked to the police also terrorize and murder favela residents. For instance, in São Paulo death squads are known for disappearing, murdering, dismembering, burning, and then scattering the remains of the dead. 28 The mothers and partners of the murdered are often left to search for their remains in order to bury them.

According to the Brazilian Forum on Public Security, between 2009 and 2016 there were over 21,892 registered deaths of people killed during police actions, not including victims of police massacres and killings by off-duty officers. 29 Roughly 76 per cent of those murdered by police were Black people, of whom 82 per cent were between twelve and twenty-nine years old, and 99.3 per cent were men. Though men make up the majority of the recorded population of people killed by police, as anthropologist Christen A. Smith explains, it is women who have to grapple with the “sequelae” of state violence in their communities. 30 In Smith’s writings on mourning among Black mothers from the state of Bahia, which has the highest concentration of Black people in Brazil, she borrows from medical terminology, sequelae, to describe the lingering and typically unquantifiable effects of state violence.

Additionally, the military police repeatedly subject Black women in Brazil to daily racialized and sexualized violence. In major cities such as São Paulo, such violence occurs in low-income as well as upper-class (read “white”) neighborhoods, to which many Black women travel for work as nannies, domestic workers, and other service jobs. Similar to women and girls of color’s experiences of racial profiling in the United States, including discriminatory use of stop and frisk, 31 Black Brazilian women are routinely stopped and harassed on the pretext that they might be carrying illegal substances. According to Giovanna Costanti, there are no reliable statistics on the frequency with which these stops occur but reports of strip searches are not uncommon. 32 While the military police are required to call women officers to strip search women and girls, they frequently do not. Survivors of police abuses report other forms of physical or psychological abuse as well. For instance, officers refer to them as “whores,” especially if they approach them in the late evening hours or when walking alone. 33

In Brazil, racialized and sexualized police violence against women is gaining more attention as the rates of women incarcerated grow. In 2017, Conectas Direitos Humanos published a report that documents known cases of torture and police abuse against Black women apprehended by the police during arrest and transport to the police precinct, to pretrial hearings, and back to their cells. 34

As a result, mainstream discourse increasingly reflects the frequency with which the military police threaten rather than protect Black women. For example, they often push working-class transgender women out of public places such as parks on the presumption that they are engaged in sex work, even though prostitution has been decriminalized in Brazil since 2002. 35 Through these policing practices, the Brazilian state treats Black women’s and queer bodies as exploitable and disposable, and renders marginalized populations as subjects to be terrorized, displaced, displayed, and, ultimately, destroyed. 36

#SomosTodasVerônica

#SomosTodasVerônica went viral and brought visibility to Verônica Bolina’s plight in the aftermath of her violent arrest. (Photo credit: Reproduction of Vitor Teixeira’s drawing “#WeAreAllVerônica.”)

On 10 April 2015, the military police arrested twenty-five-year-old Black transgender woman Verônica Bolina on an attempted murder charge in the aftermath of a physical altercation with an elderly neighbor in the middle-class neighborhood of Bela Vista in São Paulo. Police reports indicate that Verônica was under the influence of illegal narcotics, while Verônica maintains that she was not. 37 Most likely, she was having a psychotic episode. 38 However, police reports in Brazil, as in other nations with racialized and sexualized police violence, are notoriously unreliable and full of inconsistencies and errors that legitimize the use of excessive force against people who allegedly break the law. 39

Once she was in custody, the military police beat Verônica multiple times, claiming she resisted arrest. Following one of these beatings, she was left alone with one of the prison guards who had dismissed the thirteen other prisoners sharing her cell before they beat her. 40 Fearing for her life, Verônica acted in self-defense when she bit off part of his ear. Police then raped Verônica, repeatedly pummeled her in the face, and kicked her all over her body. The beatings were so severe that one of her breasts was punctured and her face was completely disfigured. 41 In media interviews, Verônica says that she thought she was going to die in custody because the beatings and tortured continued. 42

Adding insult to injury, the military police turned this horrifying abuse into a semipublic spectacle. They took photographs and videos that they then circulated in a WhatsApp group in which they regularly exchanged images of their exploits. 43 Verônica’s sexual assaults and severe beatings were clearly a sport for them.

It was not long before images of Verônica, with a bloodied and disfigured face and ripped clothing exposing her breasts and buttocks, taken in the courtyard of a pretrial detention center for men in São Paulo, were circulated to activist LGBT groups and eventually leaked to the press, garnering local and international attention. As anthropologist Marcio Zamboni details, in the wake of disparaging and dehumanizing media reports about Verônica that referred to her using masculine pronouns, ignored her brutalization at the hands of authorities, and amplified the gravity of her attack on the jailer who beat her, LGBT and human rights groups in São Paulo sought to create a counternarrative. 44 It is unclear who began #SomosTodasVerônica on 13 April, three days after her arrest and beating, but it gave visibility to the torture she was subjected to while in state custody. The following day, a Facebook page by the same name was started and became a focal point to support Verônica, attracting the attention of leftist activists and artists alike. 45 #SomosTodasVerônica used the juxtaposition of before and after pictures, which highlight her unrecognizable face after the beating, to rally support for her and to denounce the abuse she suffered.

The military police’s use of these images, specifically their circulation on social media to show off their exploits, demonstrates the state’s disregard for Black transgender women. Transgender rights activists’ mobilization of these same images, however, expanded the conversation to shed light on the ubiquity of violence not only against cisgender women and men, but also against Black transgender women. I submit that it was the intervention of human rights groups; the support of her family, friends, and her lawyer in São Paulo; and the global denunciations of the crimes Verônica endured that contributed to her survival and subsequent release from prison in May 2017.

In late September 2017, Verônica once again entered surtos (a prepsychosis state that some people with schizophrenia experience) and called on her friend Pedro to accompany her for medical treatment. The weekend of 1 October, Verônica and Pedro were set to meet, but she never showed. Soon after, she experienced a full-blown psychotic episode and was arrested.

This second arrest, while not as physically violent as the first, further demonstrates how the criminal justice system polices and punishes Black transgender women, as well as how it inflicts violence on individuals whose mental health needs are not met. The military police claim that they arrested Verônica for attacking a homeless person and that she was homicidal. Shortly after, they brought her to a psychiatric hospital. The doctors medicated her and released her without informing her family, friends, lawyer, or even the police who had brought her in. At some point later the same day, she ended up back in military police custody. They transported her to the same pretrial detention center for men in which she had been tortured and beaten in 2015 and placed her with the general population. The authorities did not notify Verônica’s family or friends of her arrest. Images of Verônica once again made the news, but this time as a missing person. The activist collective Marchas das Mulheres Negras de São Paulo (March of Black women of São Paulo) created a notice that was circulated online to help find Verônica:

An announcement of Verônica’s disappearance in October 2017 and an urgent plea to help in find her. The accompanying text describes her psychotic episode, arrest, and transport to a psychiatric hospital where she was medicated and released without informing her family, who live in the interior of the state of São Paulo and who were making their way to the city center to search for her. (Photo credit: Marcha das Mulheres Negras de São Paulo, 2017)

For forty-eight hours, friends and family desperately searched for Verônica in areas she frequented throughout São Paulo. Fearing the worst, and with no information on her whereabouts, her family filed a missing person’s report. It was only then that they found out that she had been arrested and incarcerated. In a brief conversation with Verônica in August 2017, she reflected on her initial 2015 arrest and explained that she survived physical punishment and confinement in a men’s detention center because she was able to draw from the affection and support of her friends, family, and an extended community of activists and lawyers who visited or wrote. In October 2017, neither the hospital nor the military police gave her the ability to receive support from her loved ones.

As of August 2019, Verônica has been detained for nearly twenty-four months and has yet to be tried and sentenced. Her community attends to her wellbeing as she is shuffled between the general population and the psychiatric hospital. In 2018, Pedro, a prisoners’ rights activist and a close friend of Verônica’s, told me that Verônica’s loved ones fear that her stay in the psychiatric hospital will be indefinite; while there are limits on the number of years a person convicted of a crime can serve (typically thirty), a person sent to a psychiatric ward in Brazil’s prison system is more likely to serve a life sentence. To be Black in Brazil is to be rendered criminal. To be Black and a woman is to be seen as criminal and sexually deviant. And to be Black, transgender, and a woman with a psychiatric condition is to be multiply pathologized and further dehumanized.

I briefly highlight Verônica’s case because it demonstrates the ways in which Black transgender women are repeatedly policed, controlled, and subjected to institutional negligence and atrocities. Arrest rates for transgender women are especially high, as police often target them. There are many Verônicas who face brutal assaults on their bodies and their psyches at the hands of police. Once in detention and in prison, they face further brutality as well as extreme isolation.

These systemic forms of dehumanization reverberate globally. In December 2017, I met with Stefanie Rivera of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project in New York City. As a Puerto Rican transgender woman who has also been subjected to institutionalized violence, Verônica’s story of abuse in police custody immediately struck a nerve with Rivera. She began to closely follow news reports about Verônica and incorporated her horrifying ordeal into law enforcement trainings on the rights of transgender people in New York. With good reason, Rivera is concerned about the dearth of information about Verônica’s recent incarceration. The slogan “SomosTodasVerônica” that first brought the world’s attention to Verônica’s plight has been painfully absent since her 2017 arrest. While there is continued support for Verônica on the local level and within her global transgender community, there is apathy within local and international media – when she is discussed at all. If we can all see ourselves in Verônica and denounce police violence, what does the present silence around her case say about the particular types of dangers that the state subjects Black transgender women to – and the limits of our ability to identify with and struggle on behalf of Black transgender women who experience police violence?

The Detention of Andreza Delgado: Arresting a Black Feminist Dissident

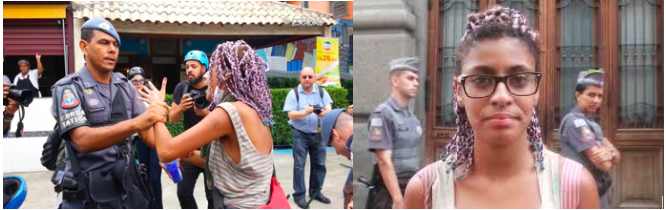

The photo on the left depicts military police apprehending Andreza during a protest against school closures in São Paulo. The photo on the right was taken shortly prior to her arrest. (Photo courtesy of Nós Mulheres de Periferia, 2015.)

In 2015, the Brazilian government issued an ordinance to defund and then close dozens of public high schools, including those in middle-class neighborhoods, across several Brazilian states. According to Semayat Oliveira, a Black feminist blogger and a cofounder of Coletivo Nós Mulheres da Periferia (We Women from The Periphery Collective), Black women were at the forefront of the student movement to occupy high schools before they were closed. 46 Andreza Delgado, a young Black college student and activist, was one of many who did so in the neighborhood of Pinheiros in São Paulo, where I lived at the time. On 3 December, the military police arrested her and some of her peers. However, unlike her lighter-skinned male counterparts, as they dragged Andreza to the police SUV they took her to an alley and sexually assaulted her. Later, during her detention, they yelled racial and sexual epithets at her and threatened to cut and burn her braids off and to shave her pubic hair. 47

Despite the media’s heavy presence; photo and video evidence disseminated online and in newspapers documenting the police’s forceful handling of high school students and their supporters throughout the city; and subsequent media interviews in which Andreza described what happened to her, the military police denied the allegations of sexual assault. In response, and as has become the norm in Brazil, both professional and amateur outlets published images of police interactions with Andreza and other students. 48 Local, national, and international outlets, such as Huffpost Brasil, believed and featured Andreza’s narrative. Even Brazil’s right-leaning daily news outlet, O Globo, denounced the police abuses to which Andreza was subjected. In other words, the police’s use of excessive force and sexual assault was plausible, if not expected.

In several reports, journalists describe Andreza as an educator, which elevates and distinguishes her from protesters subjected to violence for no reason other than exercising their democratic rights for the sake of younger students’ educations. Journalists knew that Andreza’s Blackness and non-normative aesthetic would inform how the audience would interpret her arrest, and that describing her as an educator would elicit sympathy from Brazilians who might otherwise dismiss her as another bandida. After arraignment, a judge granted Andreza’s release, which enabled her to return to the occupation. In addition to continuing to support student efforts to stop the closure of their schools, she also testified about her experience of police custody. 49

Andreza’s mistreatment at the hands of police is all too common for Black-presenting women, whether they are protesting the government shutdown of public schools or engaging in everyday activities such as taking their children to school 50 or picking up bread for their families. Andreza’s violent arrest and sexual assault is particularly emblematic of the state violence that the military police routinely enact on Black women’s bodies. Additionally, the gendered violence that defined Andreza’s arrest after her act of peaceful civil disobedience sheds light on the types of abuses that Black dissident bodies in Brazil are subject to when they come into contact with law enforcement. The military police acted against Andreza with impunity despite the dozens of eyewitnesses, bystanders, and media outlets recording their actions, which reveals the operation of federal and state policies that require customary police violence against Black people. While in the context of a protest white and middle-class Left-leaning proponents of civil rights in Brazil understand the forceful arrest of a young Black woman as violence, those who advocate security by whatever means necessary see the rough tactics as a testament to the state’s commitment to its “war on crime.” In other words, they see the violence that Andreza and her peers were dealt by the police as signs of a Brazilian government that is working to maintain public security for its desirable (read white and upper-class) population. After all, the police have been perfecting the surveillance, harassment, and murders of Black people since Brazil’s colonial era. The presence of a Black woman protesting in a white space – the high school and the middle-class neighborhood of Pinheiros – was thus perceived as not only a political threat, but also a criminal one.

By returning to the site of the protest to give her testimony, Andreza interrupted the silence around routine state violence within Black communities. In the tradition of Black activists in the diaspora, Andreza went public with her humiliating and violent detention, and appears in videos shared on social media where she describes the excruciating details of her arrest. In the videos and in her daily life, Andreza presents herself as a militant Black feminist using ethnic markers such as colorful braided hair extensions, piercings, and other African-inspired styles linked to a politicized Afropunk consciousness. Her choice to present this Black aesthetic is a threat to the white supremacy that underpins social expectations and expressions for Black women, especially in Brazil, which values the nation’s African cultural roots – the food, the music, the language – but does not value people of African descent whose phenotypes reflect this heritage. 51 Andreza’s choice to use these potent symbols of Black Power is not only a question of style, but also one of politics. White supremacy would dictate that Andreza, a self-identified periférica (woman from the peripheral lower-income favelas peppered throughout São Paulo), should neither be in university nor protesting for others’ right to an education.

As a radical Black feminist writer for Blogueiras Negras and politically engaged student activist on campus and on the streets, issues of police violence were not new to Andreza. In fact, her detention during the school occupation was not her first encounter with the police. She had written on the issue of police violence – specifically the military police’s penchant for dragging Black bodies (alive or deceased), including the murder of the late Claudia da Silva Ferreira in Rio de Janeiro, as well as her own experience of being violently dragged through the streets during an action in São Paulo in an incident that was caught on video, shortly after a 2014 arrest when she was still a minor. 52 This third incident of spectacular violence against the Black female body shows the same tactics that have always oppressed Black people by those who benefit from maintaining the status quo. The idea is to terrorize, displace, display, and, ultimately, destroy Black people. Andreza’s actions resonate with the tactics Black women have employed in the context of the civil rights era in the United States, and most recently in #BlackLivesMatter and #SayHerName, which have arisen in the wake of deadly or highly traumatic police and vigilante violence against Black people.

Conclusion

The normalization of police violence against Black women in Brazil not only allows it to proliferate in day-to-day interactions, but also produces the spectacular political violence we witnessed in March 2018 with Marielle Franco’s assassination and the sexualized police violence against Verônica Bolina in April 2015 and Andreza Delgado in December 2015. While the collective denunciation of police and state crimes in response to these egregious incidents is promising, one has to wonder if there is any end in sight to the policing and violence that target Black women in Brazil. In the context of this multihued and multiracial nation, where the majority of the population – and the police – are Black, the connections between the policing of Black women and the maintenance of white supremacist state and a politically divided populace merit careful scrutiny.

Social protest in the wake of these distinct but related forms of state violence illuminates the dehumanizing practices that are frequently deployed against Black people. Whether Black women push back through political channels, self-defense, or nonviolent protest, disrupting the status quo has had, and will continue to have, severe consequences. Yet even with this knowledge, feminist movements such as #NemUmaMenos and #SomosTodasVerônica grow in response to the frequency of gendered violence against women. Black women continue to organize and participate in actions for the welfare of their communities and ultimately for a truly democratic Brazilian state. 53 As the targets of state violence, Black women continue to ask why a Black empowered woman offends and continue to refuse the consequences for themselves and Black communities.

- I wish to thank the Ruth Landes Memorial Research Fund for supporting twenty-five months of research in São Paulo, as well as the BCRW staff, especially Dr. Tami Navarro, special issue guest editors Andrea Ritchie and Levi Craske, and two anonymous reviewers. My heartfelt thanks to Pedro, Verônica Bolina, Stefanie Rivera, Lilyth-Ester Grove, and Dr. Dani Merriman. My deep gratitude to Lindsay Ofrias Terranova, Dr. Steve Lamos, Mónica Perry, and Lorenna Mena for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article. All translations are mine. All errors are mine.[↑]

- Nênis Vieira, “O incômodo causado por uma negra empoderada,” Blogueiras Negras, 13 November 2014, http://blogueirasnegras.org/2014/11/13/o-incomodo-causado-por-uma-negra-empoderada/. In this article, I use “women” to refer to cisgender, transgender, and gender nonconforming women. If I discuss issues that are specific to the experience of one of those specific groups, I use the appropriate prefix. I do so following feminist intersectional thought, which redefines the complex category of “woman” as a social construction and not an essentializing descriptor. See Monique Wittig, “One Is Not Born a Woman,” in The Straight Mind and Other Essays (Beacon Press, 1992), 9–20; Linda Nicholson, “Interpreting Gender,” Signs 20, 1 (Autumn 1994): 79–105; Chandra Mohanty, “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” in Feminism without Borders (Duke University Press, 2003), 17–42.[↑]

- According to the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatísticas (Brazilian institute for geography and statistics), 54.9 per cent of Brazilians identify as Black, including Pardos (Brazil’s mixed-race populations of African descent). In this article, I follow that categorization and use Black and/or dark-skinned, which is inclusive of Pardos. Adriana Saraiva, “População chega a 205.5 milhões, com Menos Brancos e Mais Pretos e Pardos,” Agencia de Noticias, 12 February 2019, https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/18282-populaca”>o-chega-a-205-5-milhoes-com-menos-brancos-e-mais-pardos-e-pretos.[↑]

- In the 1930s, upon returning from the United States and witnessing the effects of racial apartheid, sociologist Gilberto Freyre coined the term “racial democracy” to describe racial relations in Brazil. He argued that Portuguese colonizers had a benevolent relationship with the Indigenous Brazilians and the African persons they trafficked and enslaved, as evidenced by the presence of mixed-race colonial subjects. For Freyre, in the postcolonial era, racial democracy persisted and defined social relations among a racially mixed unified nation of Brazilians. Scholars of Brazil have since decried the “myth” of racial democracy in Brazil. Gilberto Freyre, Casa Grande & senzala: Formação da familia Brasileira sob o regimen de economia patriarchal (Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Maia & Schmidt, 1933).[↑]

- I use “policing” to refer to disciplining practices enacted by law enforcement, prison authorities, and vigilantes, as well as by everyday citizens who, though perhaps not as lethally as the military police, contribute to the gendered and racialized violence inflicted on Black women.[↑]

- Hereinafter “Black feminists” or “Black women.”[↑]

- In 2017, Marielle ran on a platform to support Rio de Janeiro’s Black and poor populations. She received the fifth highest number of votes for city council and became one of fifty-one candidates and only one of two PSOL members elected. She was sworn into office on 1 January 2018.[↑]

- There was a third person with Marielle and Anderson in the car that evening: journalist and former aide Fernanda Gonçalves Chaves. Chaves sustained shrapnel injuries, but survived. See Editorial Staff, “‘Presença de Marielle incomodava,’ lembra ex-assessora da vereadora,” Brasil Atuação, 23 January 2019, https://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/politica/2019/01/presenca-de-marielle-incomodava-lembra-ex-assessora-da-vereadora.[↑]

- Glenn Greenwald, “Marielle Franco: Why My Friend Was a Repository of Hope and a Voice for Brazil’s Voiceless, before Her Devastating Assassination,” Independent, 16 March 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/marielle-franco-death-dead-dies-brazil-assassination-rio-de-janeiro-protest-glenn-greenwald-a8259516.html. The car she was in the night of 14 March 2018 was riddled with bullets, the same type the military police used in São Paulo in the massacre of seventeen people in the peripheral city of Osasco in August 2016. See Leslie Leitão, “Munição usada Para matar Marielle é de lotes vendidos para polícia federal,” O Globo, 16 March 2018, https://g1.globo.com/rj/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/municao-usada-para-matar-marielle-e-de-lotes-vendidos-para-a-policia-federal.ghtml. See also Kia Caldwell et al., “On the Imperative of Transnational Solidarity: A US Black Feminist Statement on the Assassination of Marielle Franco,” Black Scholar, 23 March 2018, http://www.theblackscholar.org/on-the-imperative-of-transnational-solidarity-a-u-s-black-feminist-statement-on-the-assassination-of-marielle-franco/.[↑]

- The year Marielle was killed was also an election year in Brazil. Her death galvanized dozens of Black women in Brazil to run for office.[↑]

- Jaime Amparo Alves and João H. Costa Vargas, “On Deaf Ears: Anti-Black Police Terror, Multiracial Protest and White Loyalty to the State,” Identities 24, 3 (2017): 254–74.[↑]

- That event was Jovens Negras Mudando Estrutura (Young Black women changing the structure). See Marielle’s last roundtable discussion: “Marielle Franco – roda de conversa mulheres negras mudando estruturas,” 15 March 2018, video, posted by Karina Cometti, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c66reiUsSbo.[↑]

- Último pronunciamento de Marielle Franco antes de ser executada no Rio de Janeiro,” 15 March 2018, video, posted by Mídia Livre, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Da7dqCqEJmA; Lígia Mesquita, “Os últimos momentos de Marielle Franco antes de ser morta com quatro tiros na cabeça,” BBC Brasil, 15 March 2018, http://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-43414709.[↑]

- In Brazil’s post emancipation period, branqueamento (racial whitening/cleansing) was state policy in the early twentieth century. The idea was to gradually eradicate the Black population – an uncomfortable reminder of the horrors of slavery – and to “advance” the Brazilian race. These ideologies mirrored the racial hierarchies embedded in most Latin American and Caribbean societies, with people of African phenotypes at the very bottom rungs and European phenotypes at the top. See Thomas E. Skidmore, Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). In the twenty-first century, these racist ideals still affect and shape political and socioeconomic relations in Brazil.[↑]

- Martha K. Huggins et al., Violence Workers: Police Torturers and Murderers Reconstruct Brazilian Atrocities (Berkeley: California University Press, 2002).[↑]

- Christen A. Smith, Afro-Paradise: Blackness, Violence, and Performance in Brazil (University of Illinois Press, 2016).[↑]

- For more on everyday violence that has plagued Rio de Janeiro’s favelas since the return to democratic rule, see Donna M. Goldstein, Laughter out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2014).[↑]

- Martha K. Huggins, “Modernity and Devolution: The Making of Police Death Squads in Modern Brazil” in B.B. Campbell and A.D. Brenner, eds., Death Squads in Global Perspective (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2000), 203–28.[↑]

- Temer’s presidency (April 2017–December 2018) was considered illegitimate by some because the parliament and judiciary system that deposed the democratically elected Workers’ Party President Dilma Rousseff removed her from office without sufficient evidence of criminal wrongdoing. As journalist Glenn Greenwald reports, “Rousseff was ousted in the name of corruption only to be replaced by a man who himself is being investigated for numerous corruption scandals, and who was banned for running for president by the court that presides over his Presidency.” Glenn Greenwald, “As Corruption Engulfs Brazil’s ‘Interim’ President, Mask Has Fallen off the Protest Movement,” Intercept, 16 June 2016, https://theintercept.com/2016/06/16/as-corruption-engulfs-brazils-interim-president-mask-has-fallen-off-protest-movement.[↑]

- Favelas are shantytowns and are majority Black or mixed-race, though it is not uncommon to see working-class white people living there as well.[↑]

- Under the Workers’ Party, a similar ordinance was implemented in the lead up to the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics to remove criminal gangs from Rio’s favelas.[↑]

- Leandro Demori et al., “Who Killed Eduardo, Matheus, and Reginaldo?,” Intercept, 21 March 2018, translated by Taylor Barnes and Andrew Fishman, https://theintercept.com/2018/03/21/marielle-franco-death-brazil-violence-police/.[↑]

- See Haroldo Ceravolo Sereza and Rafael Targino, “Não é só Marielle: Conheça mais 24 casos de lideranças políticas mortas nos últimos quatro anos,” Opera Mundi, 15 March 2018, http://operamundi.uol.com.br/conteudo/geral/49021/nao+e+so+marielle+conheca+mais+24+casos+de+liderancas+politicas+mortas+nos+ultimos+quatro+anos.shtml.[↑]

- For more on Malunguinho, see Aurora Ellis, “‘As Long as They Don’t Kill Us, We Will Survive’: Brazil’s First Black Trans Lawmaker Resists Fear,” Huffington Post, 8 March 2019,

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/erica-malunguinho-black-trans-brazil_n_5c7828b8e4b0952f89dfa406.

[↑] - A 2017 report from the Brazilian National Penitentiary Department highlights that in the span of sixteen years, women’s incarceration in Brazil has increased by 698 per cent. Brazil holds the fourth largest prison population globally, and the fifth largest population of women held in women’s prisons. Ministério da Justiça, “Levantamento nacional de informações penitenciárias,” Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, June 2017, http://depen.gov.br/DEPEN/noticias-1/noticias/infopen-levantamento-nacional-de-informacoes-penitenciarias-2016/relatorio_2016_22111.pdf.[↑]

- The ratification of new drug laws in 2006 ushered in an era of mandatory sentencing, which for drug offenders carries a minimum of five years.[↑]

- Alves and Vargas, “On Deaf Ears.”[↑]

- See Jamie Amparo Alves, “From Necropolis to Blackpolis: Necropolitcal Governance and Black Spatial Praxis in São Paulo, Brasil,” Antipode 46, 2 (2013): 323–9, for his ethnographic account of death squads in São Paulo’s favelas and how the women of these communities reclaim their agency in the midst of government-sponsored terror.[↑]

- Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, Anuário Brasileiro de segurança pública (São Paulo, SP Brasil, 2017), 6–9, ; Thiago Amâncio, “Policias matam e morrem mais no Brasil, mostra balanço de 2016,” Folha de S. Paulo, 30 October 2017, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2017/10/1931445-policiais-matam-e-morrem-mais-no-brasil-mostra-balanco-de-2016.shtml.[↑]

- There are no reliable statistics on the number people murdered by the police, particularly where transgender women are concerned: if a transgender person is killed by police, if they are at all counted, they will be designated by the gender they were assigned at birth. Christen A. Smith, “Facing the Dragon: Black Mothering, Sequelae, and Gendered Necropolitics in the Americas,” Transforming Anthropology 24, 1 (2016b): 31–48.[↑]

- Andrea J. Ritchie, Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017).[↑]

- Giovanna Costanti, “Enquadradas: A violência de gênero nas abordagens policias,” in Ponte: Direitos Humanos Hustiça e Segurançå Pública, 23 October 2017, https://ponte.org/enquadradas-a-violencia-de-genero-nas-abordagens-policiais/.[↑]

- Costanti points out that Black college students too, report being approached by the military police on their way to school. It is not uncommon, for instance, for the police to only stop a Black student walking along with white friends, the rationale being that a Black student is still pretx, pobre, e perifericx (a Black, poor, peripheral-dwelling individual) who does not belong among this population.[↑]

- Conectas Direitos Humanos, Tortura blindada: Como as instituições do sistema do justiça perpetuam a violência nas audiências de custódia (São Paulo: Conectas Direitos Humanos, 2017), At the site of arrest, police violence can take the form of sexual abuse; physical abuse, including spanking, electric shocks, punches, kicks, and hits to the head; and verbal abuse, including threats of rape or holding women at gunpoint and threating to kill family members. The Conectas report provides excerpts from detainees’ testimonies detailing these and other traumatic experiences with the police. ((One testimony that stands out is that of a dark-skinned detainee who, while being beat by the police, was told that because dark skin conceals bruises more easily there would be no way to prove that physical abuse had taken place. Conectas Direitos Humanos, Tortura blindada, 43.[↑]

- Sex in exchange for money is not illegal in Brazil but running a brothel is.

See Carta Capital, “Travestis relatam a perseguição de policias no centro de São Paulo,” 18 October 2017, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=plw3dmqzhZA.

[↑] - “Queer” is not a term typically used in Brazil, rather LGBT-identified individuals and others who do not subscribe to heteronormative notions of gender use words that mean “gender dissident” or “gender nonbinary.”[↑]

- VeveBolina, Instagram post, 28 May 2017, https://www.instagram.com/p/BUo7pXzBX8Y/?hl=en&taken-by=vevebolina.[↑]

- Author’s interview with Pedro, October 2017. Pedro explained that after Verônica’s first arrest, she was seen by a psychiatrist who diagnosed her with schizophrenia with symptoms of bipolar disorder, however she was given tranquilizers, a common practice for inmates in Brazil. When Verônica went missing in the aftermath of her second arrest, her community was also forthcoming about her mental illness. See also Verônica’s interview: Rute Pina, “Verônica Bolina: ‘Estou recomeçando, reconstruindo minha vida,’” Brasil de Fato, 25 July 2017, https://www.brasildefato.com.br/especiais/veronica-bolina-estou-recomecando-reconstruindo-minha-vida/.[↑]

- Maria Gorete Marques de Jesus, “‘O que está no mundo não está nos autos’: A construção da verdade jurídica nos processos criminais de tráfico de drogas,” “dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2016, http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8132/tde-03112016-162557/.[↑]

- Marcio Zamboni, “Somos todas Verônica?: Violência policial, enquadramento, e comoção,” Anais do I Seminário Nacional de Sociologia da Universidade Federal de Sergipe (27–9 April 2016): 824–44.[↑]

- Zamboni, “Somos todas Verônica,” 833.[↑]

- Pina, “Verônica Bolina.”[↑]

- “Ibid. See also Bruno Paes Manso, “Homicídios, promessas de vingança, medo e o recorde da Violência policial em SP pós Whatsapp,” Vice Brasil, 1 April 2015, https://www.vice.com/pt_br/article/mgq5jv/homicidios-promessas-de-vinganca-medo-e-o-recorde-da-violncia-policial-em-sp-pos-whatsapp. The image of a bloody officer missing part of his ear also circulated online. Zamboni points out that while some news reports cropped the photo to only show the jailer’s head and mutilated ear, in another report where the full image is used, to the surprise of many the jailer appears to be smiling as if “he were enjoying the situation.” Zamboni, “Somos todas Verônica,” 829.[↑]

- Zamboni, “Somos todas Verônica,” 828–9.[↑]

- Ibid., 836.[↑]

- See Semayat Oliveira’s interview with Andreza Delgado where she details the violence she endured. Semayat Oliveira, “‘Policía me apalpou, disse que ía cortar minhas tranças e me chamou de macaca’: Andreza Delgado educadora em luta,” Nós Mulheres da Periferia, 12 December 2015, http://nosmulheresdaperiferia.com.br/noticias/a-policia-me-apalpou-disse-que-ia-cortar-minhas-trancas-e-me-chamou-de-macaca-andreza-delgado-educadora-em-luta/.[↑]

- Andreza Delgado quoted in Karina Godoy, “Jovem diz que sofreu abuso sexual de PMs ao der Detida em protesto em SP,” O Globo, 9 December 2015, http://g1.globo.com/sao-paulo/escolas-ocupadas/noticia/2015/12/jovem-diz-que-sofreu-abuso-sexual-de-pms-ao-ser-detida-em-protesto-em-sp.html.[↑]

- Especially after Brazil’s Arab spring in June 2013, which also saw feminist-led demonstrations protesting sexual assault against women, there has been significant coverage of grassroots movements addressing a range of issues including to protest the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff (2016), and the imprisonment of former President Lula (2018), both of the Workers’ Party. The fact that this school occupation occurred after the protests of June 2013, a turning point in student-citizen-led activism in Brazil’s history, is critical to understanding the significance of performances of dissent for Black activists.[↑]

- Godoy, “Jovem diz que sofreu.”[↑]

- On 8 April 2016, while taking their fourteen-year-old to school via motorcycle, military police stopped Luan Barbosa dos Reis, a gender nonconforming Black lesbian. When Luan refused to be searched by the male officer who stopped them as a result of racial profiling, the officer beat Luan. Luan died four days later as a after severe brain hemorrhaging and a stroke. For more information on Reis’s case, see Natália Corazza Padovani, “‘Luana Barbosa dos Reis, presente!’: Entrelaçamentos entre dispositivos de gênero e feminismos ocidentais humanitários diante violência de Estado,” in Fábio Mallart and Rafael Godoi, A rota das Prisões Brasileiras (Editora Veneta: São Paulo, SP, 2017), 99¬–113;

Juliana Gonçalves, “Morta por ser lésbica: Um dossiê inédito sobre O lesbocídio no Brasil,” Intercept Brasil, 7 March 2018, https://theintercept.com/2018/03/07/lesbicas-mulheres-mortes/; Christen A. Smith, “The Canary in the Mine: Anti-Black Violence and the Paradox of Brazilian Democracy,” Portal, 29 July 2016, https://llilasbensonmagazine.org/2016/07/29/the-canary-in-the-mine-anti-black-violence-and-the-paradox-of-brazilian-democracy/.

[↑] - Abdias do Nascimento, O genocídio do negro brasileiro: Processo de um racismo mascarado (São Paulo, SP Brazil: Perspectiva, 2016 [1978]); Smith, Afro-Paradise; João H. Costa Vargas, “Gendered Antiblackness and the Impossible Brazilian Project: Emerging Critical Black Brazilian Studies,” Cultural Dynamics 24, 1 (2012): 3–11.[↑]

- See Andreza Delgado, “De Claudia Ferreira à Andreza Delgado, os corpos pretos continuam sendo arrastados,” Blogueiras Negras, 24 October 2014, http://www.blogueirasnegras.org/2014/10/22/de-claudia-ferreira-a-andreza-delgado-os-corpos-pretos-continuam-sendo-arrastados/. On 16 March 2014, Ferreira was on her way to get bread for her family when the military police shot her four times and dumped her in their vehicle’s trunk. On the way to the hospital, the trunk popped open. The police dragged her bloody body 250 meters through the streets of Rio de Janeiro in broad daylight. They then brought her lifeless body to the hospital where she was pronounced dead on arrival. This horrifying ordeal was caught on video by a driver who was following behind the police SUV. Camilla de Magalhães Gomes, “Claudia Silva Ferreira, 38 anos, auxiliar de limpeza, morta arrastada por carro da PM,” Blogueiras Feministas, 18 March 2014, http://blogueirasfeministas.com/2014/03/claudia-silva-ferreira-38-anos-auxiliar-de-limpeza-morta-arrastada-por-carro-da-pm/. See also “Mulher arrastada por viatura da PM do Rio – Claudia da Silva Ferreira,” 21 March 2014, video, posted by Jamil Souza, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycWEqo9TeSQ.[↑]

- #NemUmaMenos originated in Argentina in the wake of a wave of gendered/machista violence against women in 2015. It has spread to other Latin American countries, including Brazil, which uses the Portuguese translation “Ni una menos.”[↑]