“But Mom, my ballet teacher can’t be a ballerina. She’s too old!” So says the ten-year-old character in my children’s book in progress, “My Ballet Teacher,” inspired by the life of my aunt, Sheila Rohan. Aunt Sheila was a dancer with the original company of Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH), an all-Black dance company founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook. Although Aunt Sheila was a constant presence in my childhood and adult life, it was not until I visited an exhibition at Columbia University that included photographs of her that the idea for this story came to me. 1

The exhibition, Arthur Mitchell: Harlem’s Ballet Trailblazer, displayed a selection of ephemera from Mitchell’s earliest professional years when he was the first Black principal dancer in the New York City Ballet. The exhibition spanned his career and life up to his death in 2018 at age eighty-four. He founded DTH with Karel Shook in 1969. Their mission was to train and showcase the brilliance of the community and to demonstrate that, with nurturing and good training, little Black and Brown kids could achieve excellence in dance, too. Mitchell built a school and a company that broke barriers. It toured around the world. For the young Black girls who were shut out of classical ballet because their bodies were not and seemingly never would be “right,” he opened a door and gave them the keys. DTH was an essential part of Black history. For my aunt, it was a source of pride. My siblings, cousins, and I grew up attending classes and performances. We, too, learned a pride at DTH that would never leave us.

As I wandered around the exhibition, marveling at the beauty and rich history of Mitchell’s collection, I came across three photos of my aunt Sheila. I had memories of seeing her dance, but I was much more familiar with images of her as a ballet teacher and leader in the community. Seeing her in these photographs, her long sharp lines and sinuous arcs, converted that familiar body into a work of art. It was like meeting my aunt in a whole new way.

Recently she told me she was almost fifty when she stopped dancing on toe. Of my mother’s seven sisters, she is the one with whom I am closest. For years, we worked together and saw each other almost daily. I did not really notice when she began to age. I experienced her physical changes gradually and slowly.

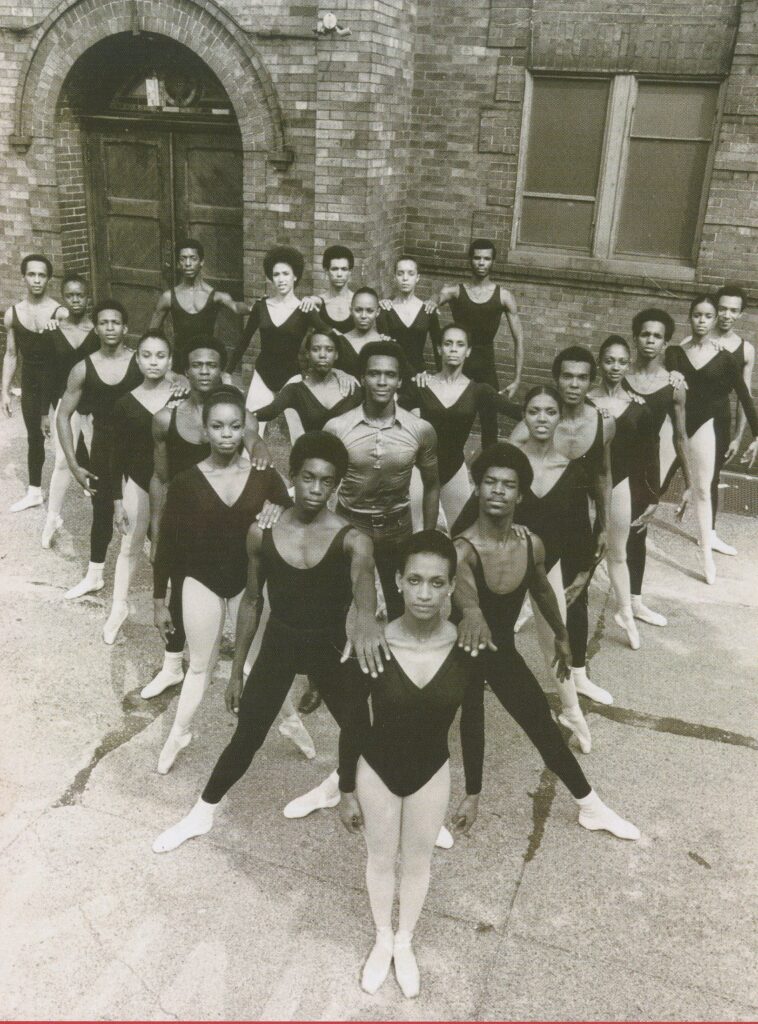

Standing in that gallery exhibition I had a revelation. Since her twenties, when these photographs were taken, Aunt Sheila appeared to have aged very little. Her beauty remained as radiant as it had been then: petite, poised, graceful in her step. Staring at the photo from 1969 in which she stands behind and to the right of Arthur Mitchell, along with twenty-two dancers in the iconic pyramid pose, I was struck by the historic nature of which she had been a part, and at such a young age. Yes, Arthur Mitchell was the primo, but he couldn’t have busted the ceiling off classical ballet without the pyramid of those others who stood with him. They cut a fierce shape. And there was Sheila in the center, all of twenty-eight years old, sporting a teeny afro, gorgeous cheekbones, and perfectly turned-out legs. By then, she was already the mother of three children.

Through the early 1970s, my cousins and I were the beneficiaries of Aunt Sheila’s dance education. Not only did we get to attend world class performances as small children, but we were also regular audiences for early DTH children’s programs and demonstrations. When Aunt Sheila was no longer touring with them professionally, she continued to work with other companies and choreographers, such as my Aunt Nanette’s dance group where she was a soloist and ballet mistress. Additionally, she taught at the Alvin Ailey School of Dance for about a decade. There she helped shape the bodies and minds of young dancers through both the youth and adult divisions. Naturally, as soon as my daughter turned five, she began her dance education there.

I remember at that time there were debates about how much time at the barre was beneficial for the four- and five-year-old kids, the ones whose bodies were still forming and full of energy, who needed to run and jump to grow. As my daughter progressed in her training, the teachers seemed to eye her potential. Apparently, she had whatever they look for. Slight proportions? Not too tall? A flare for drama? I’m not sure. My daughter was an adolescent then, the time when a child’s body is maturing and the need to strengthen and shape it becomes more intense. It’s a make-or-break moment for many. At the point of entering high school, my daughter chose a different route. Those who go on to train professionally give their bodies over to the form to excel. And the practice is forever inscribed onto their muscles.

Now in her eighties, Aunt Sheila maintains a regimen of ballet movements with a group of older dancers.

Anyone who knows me knows I can be on the dance floor from dawn to dusk. These days, after a long night of dancing, I feel only a little sore the next day. In a past life, I must have been a professional dancer. In this life, I have a repertoire of movements that I feel will never go out of style. On any dance floor, at any hour, I am in my own world. With or without a dance partner, I cha-cha and twirl, two-step, and shimmy, swaying my head to the lyrics. As my body has aged and thickened, I wonder if I look awkward and out of step. But I don’t feel it.

Still, I’m careful to stick to appropriate dances for my aging body. No matter how much my Caribbean soul feels the beat, I will never be seen twerking, death dropping, or spinning on my back.

Dance is not just about the ability to move, it takes expression. Perhaps older dancers adjust for slower bodies and less range by connecting more with the ideas. I think back to an inner-body experience when my vain, adult self called on the superhero of my youth. It was during a field trip to the park with my daughter’s class. The children gathered to jump rope and my inner child jumped for a turn to shine: a chance to play double Dutch. When I was in elementary school in the 1970s, I was an average jumper. But this was a Black girl’s playground occupation. In the 1980s, African American girls and boys so dominated games of double Dutch with speed and innovative style that it ballooned into an internationally recognized sport.

The combination of rhythm and dance in double Dutch made an indelible mark on my preadolescent body. My daughter’s field trip wasn’t the only time I felt the urge to take a turn. I occasionally came across girls playing on the sidewalk, and, not that I had anything to prove, but I longed to feel that rush of getting my body into the space between two opposite-swinging ropes at just the right time, not to disrupt their flow. Once inside, you are held if you skip, balance, keep speed, keep concentration, and dance. If you miss, you get tangled. You lose your turn.

At the time of that field trip, I had no idea if jumping in the game would look cool or scar my daughter for life. Not to mention possibly injuring myself. But the urge was so great, helped along by two other Brown mamas willing to take turns, it won out over any pretense of decorum. It was exhilarating to defy gravity suspended between the ropes for just a few moments. The memory of my eleven-year-old self would not allow my thirty-five-year-old self to care about how I looked, only relish in how it felt to move.

Periodically, I find my way to some kind of dance, exercise, or yoga class. And here my limitations emerge. I’ve been most humbled in ballet classes with dancers ten to twenty years older than me, many of whom are friends and former colleagues of Aunt Sheila. In the past, Aunt Sheila was usually the ballet mistress, but occasionally someone else took the lead in independently arranged sessions. In those evening classes, I learned never to underestimate the power of muscle memory. Those aging Black bodies could and did kick higher, leap further, and remember the choreography more quickly than me. Those dancers whose bodies were no longer “right” for the profession, maybe never were, never stopped practicing the form in their bodies. There may be a little softness around the edges, but they are still muscular and strong. They can pirouette and arabesque like nobody’s business. They still take care of their bodies and still scrutinize themselves in the mirror. Many of their performing careers have morphed into other shapes: teaching, choreography, advocacy, and leading small companies.

Dance shapes the body. You can often spot a dancer, even in old age. She has a straight back, a head held high, legs turned out, a graceful movement in her hands, a flare for the dramatic. She feels herself forever a dancer. She can be serious and poised, but she can laugh at herself too.

From 2018 to 2020, I was on the board of 5 Plus Ensemble, whose founders included Sheila Rohan, Hope Clarke, and Carmen de Lavallade. Their mission was to showcase dancers, choreographers, and musicians over the age of fifty. Instead of waiting for anyone to hire them or closing the door on their artistic lives, they made their own opportunities. 2 As part of a dance festival, 5 Plus dancers performed a skit-like dance about a group of dancers taking a ballet class for people over fifty. The dance was called “Getting It Together.” Performers mimed exaggerated moans and groans as they stretched. They mimicked the hassle of trying to warm up their old bodies and getting to class on time. But once class started, they “got it together.” They were on point. Their souls were brought to life by the rigors of the barre exercises. Later, the dance satirized the competitive side of this world. Each dancer took a moment to show off. At the end, barre class over, they returned to their former selves. The tired, slumped-over old bodies trudged off the stage. 3

“Getting it Together” reminded me of a story I once heard about Josephine Baker, who performed well into her sixties. By that point, she was very much an old lady who slumped to the stage. But as soon as she stood under the lights, she came alive. She performed as she always had, miraculously.

*

While writing this piece, I was happy to find myself in the company of a few former members of DTH, some of whom began dancing with the company in 1969 and others in the early 1970s. They had recently formed a new organization, the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy, whose mission is “to collectively preserve, educate and give voice to the essence of Black Ballet.” One evening in 2021, I had an opportunity to dine with the five members in midtown Manhattan. Earlier that day, they had gathered for a photoshoot for a forthcoming article in The New York Times. It had been an exciting moment for them, suddenly thrust into a limelight they hadn’t seen in decades. They relished it. At dinner, there was talk about how the producer selected outfits and makeup: all wrong. They did not want to look like overly made-up has-beens in house dresses. They had always been and always would be performers. They knew how to shine.

While they talked, I found myself anxious to ask them questions. I wanted to hear in their words what it was like to age, and how they felt perceived as older dancers in their profession. I imagined horror stories. Being passed over for younger dancers. Left hung out to dry. Desperately trying to beat the effects of aging. I was certain that as young dancers they had dreaded the moment when they would age out, let go by their companies because their instrument had lost its tune. To my surprise, they told me that they had never thought about a horizon. They assumed they’d dance all their lives. And they do, in one form or another.

But, for many of them, there came a time when something changed. When they realized they didn’t want to do it anymore. The moves and jumps became more difficult. They found it harder to retain steps and remember complex combinations. Younger people were doing amazing things with their bodies while injuries were taking a toll on them. Some were in constant pain. They all laughed as they traded stories of famous dancers who had performed long past their prime, who seemed, to them, ridiculous. Aging wasn’t the only factor that had caused these dancers to leave the profession. Many never made enough money to support themselves. 4

As I approached a milestone birthday of my own and the young people in my life become full-fledged adults, aging seems to be the topic of discussion everywhere. Yet I have worn the badge of “never aging” for a long time. I still get carded at clubs. People are shocked to learn my daughter is thirty-two. But I shrink at the phrase “Black don’t crack.” I half expect an avalanche to split through my body any day now, although I’m comforted by the real science behind the adage. Melanin offers enhanced protection from the sun.

Science aside, I only had to look at my family to know I was lucky in the gene pool, being both youthful-looking and strong-willed. For most of my life, I didn’t worry about self-image. I didn’t have to confront a body that I couldn’t control, or a body that transgressed the accepted bounds of shape, size, and desirability. But over time, life challenged my body. As I began to age, I found myself navigating a new relationship. Now I must recognize my body anew to re-encounter it, and to encounter a world that sees me differently.

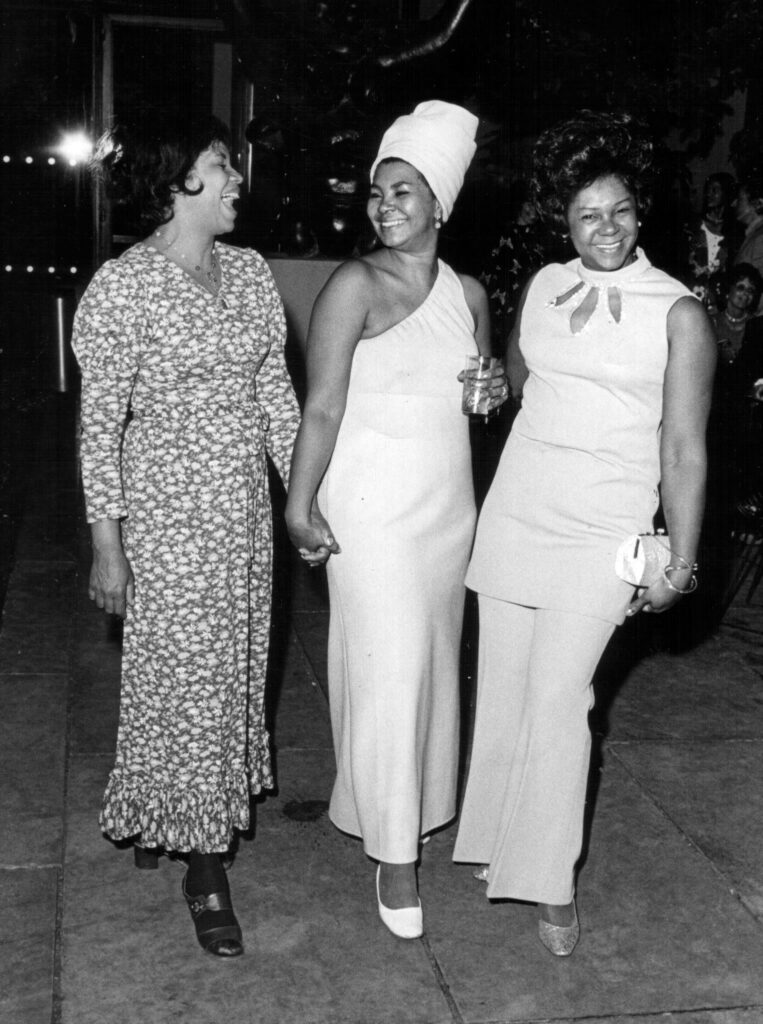

Again, I find solace in my family. For clues to navigate the maze of my own maturing body, I look to the photographs of my mother and aunts in midlife. They were beauties. One of my favorite photos features my mother in the middle, flanked by her older sister Nanette and their eldest sister Evelyn. In this picture, I see three women, models of maturity and style, who feel beautiful and live out loud. Though they are captured candidly, I sense that they knew they were giving me a gift, a photograph I would treasure for generations.

*

My aunt Nanette was also immersed in the world of dance. A model and aspiring dancer in New York City in the mid-1940s and early-1950s she moved in a circle of heavy-hitting creatives. Her husband was renowned artist and writer Romare Bearden. The arts were the hub of their life together. In 1972, Nanette founded her own dance company, the Chamber Dance Group. According to her artistic director Walter Rutledge, the company helped her maintain her own identity separate from Romare the Artist. Like others in our family, Nanette possessed a deep desire to help Black people and practiced this in her company, promoting Black dancers and teachers in their careers.

Nanette was exceptionally beautiful. She knew the rare opportunities she’d been afforded as a model. When she was in her late twenties, she was courted by both Bearden and Joe Louis, the professional boxer, or was it the other boxer, Sugar Ray Robinson? As Walter recalls, Nanette’s mother thought the boxer wouldn’t be a good choice as he’d be “punch drunk.” 5

Looking to escape a conventional life, she chose to marry the artist and go the bohemian way. She and Romare left Harlem for a downtown loft on the edge of what would later become SoHo, near Chinatown and the old Pearl Paint art supply store. Bearden’s career took off. Nanette was swept up in the whirlwind of attention and the demands of public life. Though they never had children, Nanette had a big family and many projects, including the Romare Bearden Foundation, which she established to maintain Romare’s legacy after his death in 1988. But the dance company was hers.

Separate from its many lofty goals, I always suspected that the real reason Nanette ran her company was so that she could dance.

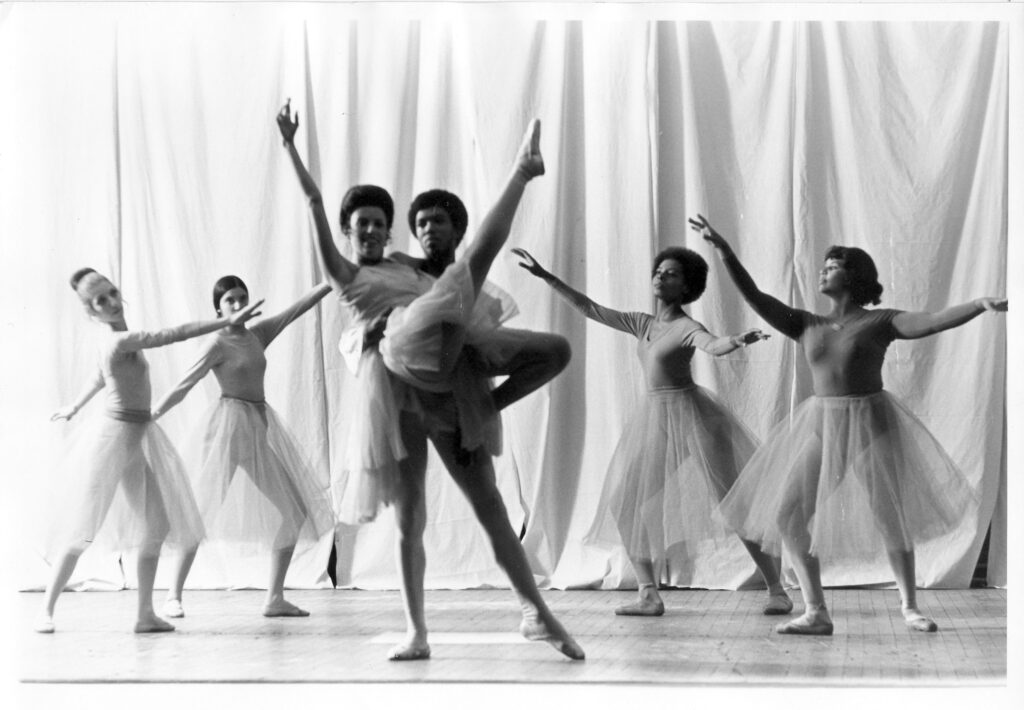

A photo from around 1976 shows Nanette performing with the Chamber Dance Group. There is Nan, far from the wings, standing on stage as an essential part of the corps. She holds her hand gracefully in the air and her head high. She gives us attitude. This was clearly not a company built on the uniformity of classical ballet. Dancers on stage displayed a variety of shapes, sizes, colors, and hairdos showcasing a range of ages and personal styles. There’s a prim ballet bun, a chignon, a high bouffant, an afro, and Nanette’s 1960s pressed pageboy. Most notable are the variety of waistlines. Nanette’s body is the thickest, and she holds it in high drama, mature, serene, and imbued with wisdom. I detect her professionalism, self-satisfaction, and pride. Being on stage, she had fulfilled her prophecy.

With her dance company, Nanette wanted to give opportunities to those who had more grit than grain, who didn’t make the cut, or who were considered past their prime. Early on, she moved to the wings of the stage, managing the company as chief strategist and fundraiser. Walter told me the company had become “a showcase for emerging choreographers.” 6 Most of all, Nanette had a muse in her youngest sister, Aunt Sheila, who she mentored through childhood, and eventually encouraged to audition for DTH.

As young people, my cousins and I snickered behind the backs of our elders. We made fun of the way they dressed, the things they said, the uncool dances. A few of the aunts and uncles were targets for our criticism, my own mother in particular. She sported afros and a huge red cape, much to my chagrin. With parents born in the Caribbean, I guess, my mother and her sisters thought it reasonable to dance on tables and laugh so loud. Aunt Sheila wore African clothes and danced as she walked. Nanette was an old bag lady—a little like me now—always carrying her stuff around. She wore plain, disheveled clothes, and on her head some kind of slightly crooked wig. We were too young to see through what embarrassed us to the glamourous model she had been in her youth. But I think we did see strength, ingenuity, and caring.

In a photograph taken in 1989, not long after her husband Romare passed away, Nanette appears seated outside of a ballet studio, dressed in a black leotard and tights. Sixty-two years old, plump, chic, and smiling. She has returned, as she occasionally did, to her love of dance. Her happiness is infectious. She glows from the inside with a young essence, a sense of freedom. She’s a full-figured, mature woman. And she proudly wears the uniform of a dancer.

Once a dancer, always a dancer.

*

In images of my mother, Annette, who also modelled, hands and hats, I see a woman always cheesing. Smiling wide, her full cheeks shining, lip-sticked and even-browed. To this day, in her late eighties, lift a camera to take a picture and she is flashing a huge grin. She is beautiful. More proof of that adage “Black don’t crack.” It’s tough praise to swallow because we all know Black bodies are some of the first to crack. Hypertension, environmental and medical racism, stressful lives, diabetes, heart disease, maternal mortality, MS, and rarities like sickle cell anemia disproportionately affect Black people, particularly Black women. My mother has had problems with high blood pressure and high cholesterol since she was a young woman. When she retired at age seventy, she was diagnosed with peripheral artery disease. Her arteries were shriveling. Stents were inserted into the veins in her legs to aid in blood flow. About three years ago, the condition worsened. Her left leg was amputated above the knee. For me, I saw a big loss to her mobility, but for her, I think, it dealt a greater blow to her vanity. She hated her “stump,” as she called it, sitting halfway in her pant leg. She hated seeing a single shoe poking out from under the hem of her dress.

But perhaps my mother, Annette, never forgot her youth as a model for she was always stylish and, even after she had her babies, she never let herself go, as they used to say. Like Aunt Evelyn, she put on makeup every day, even at home in retirement. After the amputation, my mother adjusted her self-image. The life of the party recalibrated to the space of a wheelchair. There’s occasionally a rush to put on lipstick and always a fussiness about her hair, a full head of thick, soft, silvery locks. But she puts it all in her smile: There lies all the light, all the glamour you need to see. Her dancing spirit is unshakeable. When I look at her, I think, I want to be the old lady they can’t get off the dance floor. On my two feet or on wheels.

*

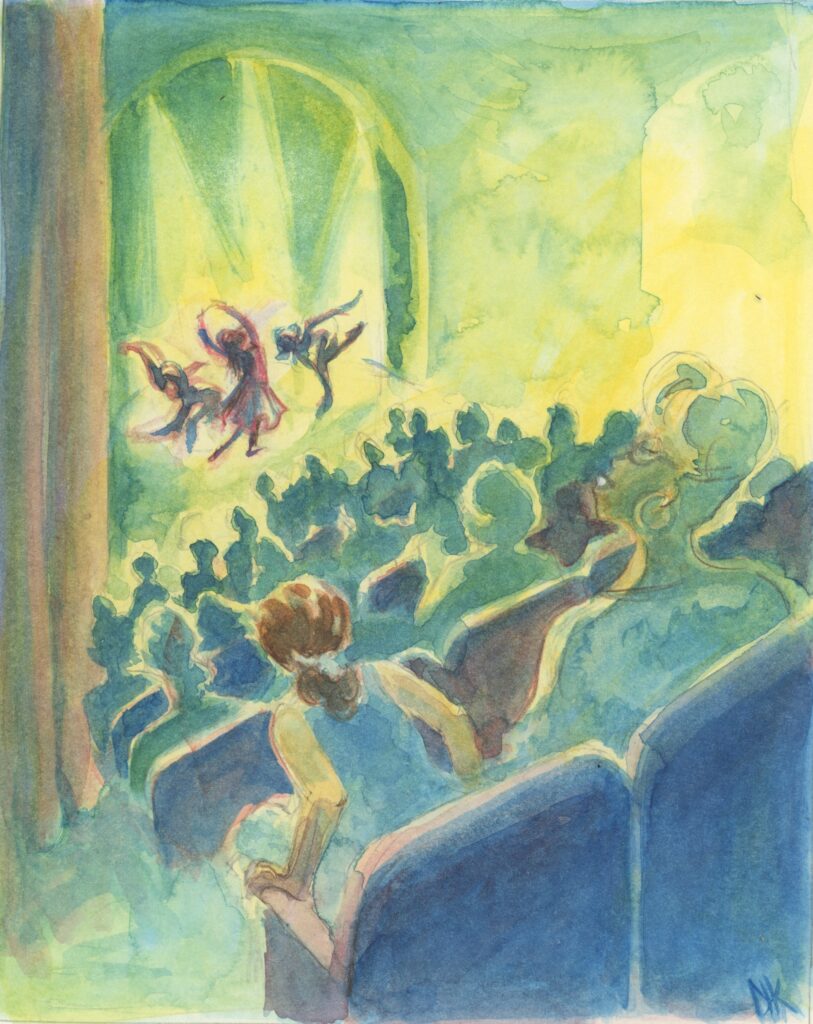

The children’s book inspired by Aunt Sheila tells the story of a little Black girl who learns about history, family, and herself through ballet. She is shocked to realize that Ms. Rohan, the old woman who teaches her class, is still a dancer. It’s a revelation. Her mother takes her to see Ms. Rohan in a performance of contemporary choreography featuring older dancers with bodies of many shapes and sizes. The little girl observes the miracles of a dancing body, its eternal grace and strength.

As I have twirled with my teachers—my mother and my aunts—trying to keep up, learning to slow down, pushing my body and resting my body in equal measure, so the little girl learns to unfold the world before her differently.

Figure list

Figure 1: Diedra Harris-Kelley. Illustration sketch.

Figure 2: Dance Theatre of Harlem company members in front of Church of the Master, 1969. Photograph by Marbeth, New York. Dance Theatre of Harlem archives.

Figure 3: Family photo of Nanette, Annette and Evelyn, c. 1970s.

Figure 4: Unknown photographer, c. 1950s. Nanette Modeling archive.

Figure 5: Unknown photographer, c.1972-74. The Chamber Dance Group. Nanette Bearden archive.

Figure 6: Ming Smith, Untitled photo of Nanette Bearden, 1989.

Figure 7: Diedra Harris-Kelley. Illustration sketch.

Figure 8: Diedra Harris-Kelley. Illustration sketch.

Works Cited

152nd St. Black Ballet Legacy members in conversation with author, June 2, 2021.

Chamber Dance Group. circa 1970. Photograph. Nanette Beardens’s personal archive. Courtesy of Sheila Rohan.

Harris-Kelley, Diedra. Woman and girl in a gallery. Illustration.

Harris-Kelley, Diedra. Woman and girl at a ballet. Illustration.

Harris-Kelley, Diedra. Woman and girl dancing together. Illustration.

“Getting It Together,” choreography by Roumel Reaux, performance by 5 Plus Ensemble, Marcus Garvey Park, New York, August 15, 2019.

Nanette, Annette, and Evelyn, Bremen ship. 1971. Photograph. Nanette Beardens’s personal archive. Courtesy of Sheila Rohan.

Nanette Bearden modeling. circa 1950. Photograph. Nanette Beardens’s personal archive. Courtesy of Sheila Rohan.

Rutledge, Walter, phone interview with author, June 3, 2021.

Smith, Ming. Nanette Bearden. Photograph. 1989.

Mitchell, Arthur. Arthur Mitchell: Harlem’s Ballet Trailblazer. January 13-March 11, 2018, The Wallach Art Gallery, New York.

- Arthur Mitchell: Harlem’s Ballet Trailblazer ran January 13-March 11, 2018 at The Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York. The exhibition highlighted the personal archive of Dance Theatre of Harlem founder, dancer Arthur Mitchell, whose archives Columbia University acquired in 2014, housed in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[↑]

- The 5 Plus Ensemble officially disbanded in 2020 during the pandemic. The principal founders included Hope Clarke, Sheila Rohan, Carmen de Lavallade, Darryl Reuben Hall, and Michael Leon Thomas.[↑]

- The piece, “Getting It Together,” was performed on August 15, 2019 at SummerStage- Marcus Garvey Park, New York as part of the Clark Center for the Performing Arts 60th Anniversary Tribute. Performers included: Hope Clarke, Audrey Madison, Michael Leon Thomas, Harrison Lee, and Walter Rutledge. Choreographer: Roumel Reaux.[↑]

- Conversation between author and members of the 152nd St. Black Ballet Legacy– Sheila Rohan, Lydia Abarca-Mitchell, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Karlya Shelton-Benjamin, and Marcia Sells on June 2, 2021.[↑]

- Phone interview between author and Walter Rutledge on June 3, 2021. The name of Nanette Bearden’s Dance company was changed from the Chamber Dance Group to the Nanette Bearden Contemporary Dance Theater when it was incorporated in 1976.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]