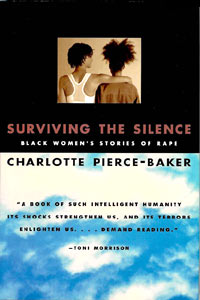

With the publication of the book Surviving the Silence: Black Women’s Stories of Rape, my personal life was understandably changed. But also dramatically altered was my academic/professional life. Surviving the Silence and its being in the world has reshaped my pedagogy. The writing of memoir and its dissemination has shifted my thinking about “theory.” There was always tension for me as I began to write. I felt as if I were forced to make a choice of which audience to “write for” – to speak to.

I believe if we are to broaden the categories of what we call “the academic” and challenge those “sacred boundaries,” books such as Surviving the Silence need to be read, critiqued, and fit into the pedagogy of and about women, especially within the arena of black women’s literature and pedagogy. Colleagues across the nation interested in issues of trauma, violence, and black women’s lives (writers, scholars, filmmakers, activists) are now more than ever working together to develop a “language” for writing and teaching in the areas of rape, sexual assault, and other traumas. Many of these colleagues, men and women, have graciously used Surviving the Silence in their college and university courses. Doing so, I believe, encourages a more expansive pedagogy on the university front. Each time, for example, that I use Dartmouth University professor Susan Brison’s academic memoir, Aftermath, or practicing psychologist Martha Manning’s professional memoir, Undercurrents, or Duke University professor and colleague Karla F.C. Holloway’s personal yet academic treatise, Passed On – when I recur to these texts – I know I am shifting and expanding the parameters of trauma, literature, theory, and the “lived lives of women.”

Graduate-student scholars have been some of my most ardent supporters, analyzing and critiquing in their classes the text Surviving the Silence. Now I better understand what I accomplished by writing through memoir; I can now evaluate the process as well as the consequences of many of my writing decisions.

It was in 1990 that I began to think about writing what eventually became (in 1998) the book Surviving the Silence: Black Women’s Stories of Rape. The book’s foundation was extremely personal: that is, it was motivated by my own rapes, rapes perpetrated by two black males – burglars, in my own home – as the legal version has it: “rapes committed in the process of another crime.” In spite of that very personal beginning, my initial thinking on the content of the book I was writing was to produce an academic piece on rape, slavery, black men and women, and the impact of sexual violence on black lives. After all, I was an academic; therefore, I told myself, I should write something totally academic – footnotes, bibliography, allusions – the whole academic bundle! My research began with the idea of producing – in book form – an “ethnography of black rape.” With this focus, all seemed to be taking shape-gaining purpose, I thought. And I began to interview black women rape survivors. The audiotapes increased in number. However, as I interviewed the women, I soon became patently aware of two things: one: I was not writing, and two: I was in denial about my own rapes. I was surely procrastinating (or what we, in the field of trauma, sometimes call “paralyzed by fear”). I had unraveled an incredibly intricate string of secrets and continued silences – and I was at the center of it all. My realization became clear: I was still “in hiding” and not openly talking about my own wounding. I had, thus, failed in the face of the first goal of writing memoir: truth telling. If I had failed at truth telling, then, how could I possibly face “objectively” and in supportive ways the other women and their narratives? The answer was, I couldn’t – nor should I ever have thought I could. In fact, the actual writing (that is, words on the page) of Surviving the Silence did not begin until I had “owned up to” my own rapes, the details, the aftermath. It was almost as if I were not allowed to transcribe the words of the other women until I had “faced myself.” It was at this juncture I realized – I was creating community. And in such a community one must share “the unspeakable.” Mine was no longer a solely academic endeavor. And it was then that I remembered feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun’s proclamation that “it is not so much women’s lack of language as their failure to speak profoundly to one another” (emphasis mine) (Writing A Woman’s Life, 43). And with that, my fingers gained strength!