This essay features a slide show. To view each slide, click on the numbered link accompanying the text as you read. Alternately, you may move between slides by using the “previous” and “next” buttons below each image.

This essay may seem to begin oddly. To address Jewish themes in my artistic work, I put before the reader a picture of myself with Marlene Dietrich. [slide 1] I do this to suggest that even in the first six months of my life I was part of fictions and masquerades such as the film from which this is a publicity still and in which my twin sister and I were passing as one baby, Marlene’s baby. Whatever ideas concerning motherhood, women and babies were being produced through this Hollywood film, my Jewish identity was more than just absent – it was completely overridden by the film’s fiction. In this film I am cast as the baby of a famous (and famously German) gentile woman.

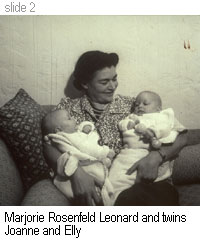

As for the telling of my own “true” [slide 2] story, I must be sure not to claim more knowledge of Jewish customs than I have, since I grew up with very little idea of Jewish life. But as far back as I can remember, I “felt” Jewish and knew that “Jewish” was something that defined our family. My dad [slide 3] escaped Nazi Germany, having grown up in a relatively assimilated German Jewish family in Mannheim. He met my mom [slide 4] when they were both students in Berlin. My mother was an American studying psychoanalysis with some of its earliest practitioners, and my dad was studying law and working for a Jewish legal defense group, the Central-Verein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens. My mom interrupted her studies and returned to the U.S. when her parents became increasingly worried about the situation in Germany. Two years later, in 1933, my dad, with help from my mother’s family, was able to come to the U.S. In that same year my parents were married in Los Angeles. My mother was a third generation American from a well-to-do family whose German Jewish members arrived in the U.S. and quickly put aside anything that might mark them as overtly Jewish. As I understand it, this quick shedding of outward “jewishness” was quite typical of German Jews who immigrated to the U.S. in the l850s, as had my mother’s grandparents. My parents started their family in Los Angeles. I was born in l940, and by the time I was old enough [slide 5] to have any sense of my family’s relation to World War II and Nazi horror, the war was over. It was a milieu of concern for social justice and intellectualism that distinguished my parents’ world in my eyes. If you’d have asked me what was Jewish about our family, [slide 6] I might have answered vaguely. It had, I might have said, something to do with art, music, politics and troubles in the world.

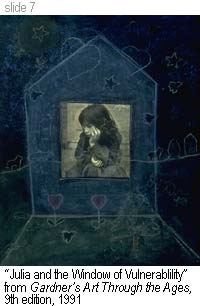

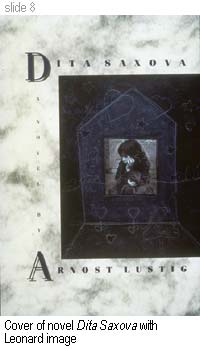

It has taken most of my years as an artist to make work that consciously addresses a Jewish identity and to think about how some of my earlier work may be a reflection of my Jewish heritage. As other authors in this set of essays have pointed out, it isn’t all that clear just how what is Jewish shows up in photographs and art work. Thus, even discounting my own meager understanding of Jewish thought and life, it isn’t surprising that Jewish themes in my work have gone largely undetected by me and others. Some of my work that has had the widest audiences suggests that everyday life is tinged with vulnerability and potential danger, as, for instance, in “Julia and the Window of Vulnerability” [slide 7] (published in 1991 in Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 9th Edition, Harcourt Brace Javanovich.) This work, it now strikes me, has within it some of the “outsider” feelings, anxiety and caution that were part of the atmosphere my father, a refugee from Nazi Germany, carried with him into our home. But when I made the work, I was focused on other ideas – particularly the vulnerability I felt as a mother to my daughter, Julia, in the Reagan era, a time when the nuclear arms buildup was being vigorously promoted. Interestingly, “Julia and the Window of Vulnerability” was employed in a distinctly Jewish context when, in 1993, it was published as the cover of a Holocaust era novel by Arnost Lustig [slide 8] (Arnost Lustig, Dita Saxova, Northwestern University Press, 1993).

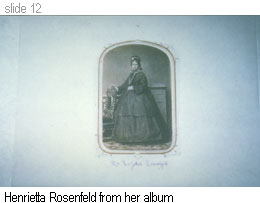

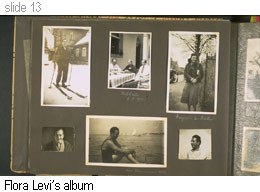

Before I tell more about my most recent piece, “Reel Family,” which is among the first works where I deliberately address Jewish stories and themes, let me say something about family albums and photographs and their place in my artistic production. I have been fascinated for years by ideas of constructing identity through photographs [slide 9] and have combed family albums for hints of the roles women have taken in picturing their family’s lives, especially through albums. [slide 10][slide 11] Among my recent works are two large pieces based on different albums kept by a grandmother and a great-grandmother on opposite sides of my family and in different centuries. I see these projects as related pieces of a larger work that addresses family stories and anti-Semitism. One such project is my great-grandmother Henrietta Rosenfeld’s album [slide 12] begun in the U.S. of 1860, and the other is an album [slide 13] begun in Germany by my grandmother, Flora Levi, in 1933. I’ll deal only with “Reel Family” in this essay.

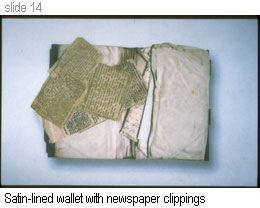

Now I turn specifically to the story behind the making of my 22-foot scroll work, “Reel Family.” I traveled to Los Angeles after receiving a grant that allowed me to leave my teaching at the University of Michigan and be part of UCLA’s Center for Research on Women. As it happened, my trip to Los Angeles came shortly after my uncle died, and my aunt needed to move from the Los Angeles home where they had lived for the past 40 years. I eagerly went to help her sort through old family papers and photos. Stashed in boxes that hadn’t been opened for most of her years in this house were immigration documents, letters and a little beaded wallet – its two inside satin pockets stuffed with tiny yellowed [slide 14] newspaper clippings that were the beginning of my work on “Reel Family.”

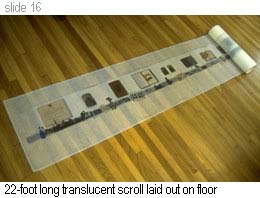

As it turned out, the little cache of clippings I’d found were all virulently anti-Semitic letters [slide 15] to the editors of New York newspapers congratulating Judge Henry Hilton for keeping Jews out of his hotel. The year was 1877. Joseph Seligman had tried to check into the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga and been refused. Because he was a prominent New Yorker, a financier once invited to be U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Seligman went public about Hilton’s refusal, believing there would be a public outcry condemning Hilton. Instead, anti-Semitism, huge and unabashed, leapt into print everywhere along with congratulations to Hilton. The little clippings preserved these dreadful letters related to the situation surrounding Joseph Seligman, a family friend to my great-grandparents, Henrietta and Lazarus. Many items I found at my aunt’s, including Henrietta’s album, pointed to the strong bonds between my family and the Seligman’s. These clippings made working with this family picture album particularly irresistible. And it was my being in Hollywood that cemented my approach to this material. I would use film as form and image borrowed from movies (the work is translucent and gives the appearance of an unwinding strip of film). But the strip/scroll form captures not only the look of film, but also of zoetrope strips (early animated drawings), medieval scrolls and the Torah.

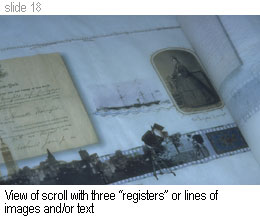

When the work was in progress, I worked on small segments at a time, rolling and unrolling the scroll to work on its various segments. The only way I could get a long view of it was to lay it out on the living room floor downstairs and go upstairs to photograph it from a small balcony in my upstairs studio. [slide 16] About all the viewer can make out in the pictures of these long views is the translucency of the glassine paper that is the background of the scroll. At the beginning of the scroll, [slide 17] a little blue figure of a female photographer is standing in for me as recorder of time passing. The scene is New York City and what the viewer sees in this first detailed view of the scroll are two of the three (from top to bottom) lines that would be revealed as one unrolled the scroll or walked along its fully unrolled length. If one were to move slightly to the right and step back a little, [slide 18] one could take in the scroll from top to bottom and see the three “registers” or lines of the scroll that run throughout. The center line has documents, photographs and book pages. The top line [slide 19] holds text; a ship bringing immigrants to the U.S. rides the text as if it were a wave.

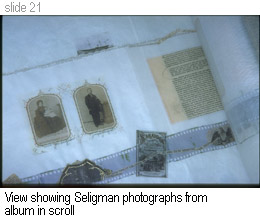

The wave of text reveals the story of the repressive laws passed in Bavaria in the 1850s that caused the wave of immigration of which my great-grandparents were a part when they came to the U.S. The facts about the laws and the resulting waves of immigration are punctuated by bits of my great-grandmother’s handwriting in Yiddish, and bits of headlines from stories of immigration in my local newspaper in the year 2000, the year I was working on “Reel Family.” In the next illustration [slide 20] of the piece, one can see the remainder of the 22-foot scroll rolled up at right. Also revealed at the left edge of the picture is the open album – showing on its pages my great-grandparents. In the next illustration [slide 21] are their good friends, the second pair of portraits in this substantial album of more than 50 photographs. Here, Henrietta has written “Joseph Seligman and Mrs. Jos. Seligman.” Such formality in the way Henrietta identified the persons in the photos might suggest distance. However, Henrietta placed the photographs of the Seligmans in her album immediately following the pictures of herself and her husband, one of the many ways she took pains to make clear the closeness of the Rosenfeld and Seligman families. Many items that made their way down through the generations (signatures on the marriage contract my grandmother’s Ida’s wedding guests signed, notations on the backs of photographs) give further indication that the two Seligmans, their decendents and my family remained close for years.

If I needed more proof that news about the Seligmans concerned my family, I found it in the very fact that the little clipping in the wallet had been preserved over generations and a period of more than 100 years. [slide 22] I was able to learn more about the public side of the story and scandal that followed by reading “The Hilton/Seligman Affair” from the book Our Crowd [slide 23] (Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York, Stephen Birmingham, Harper and Row, 1967). It is the parallel lines – of personal and public stories – that I’ve tried to capture through the formal devices of linear presentation in my film-like scroll work, “Reel Family.”

Ironically, it was anti-Semitism that had sent my great-grandparents to America where they did everything they could to join the melting pot and lose their ethnic identity. Many, predominantly Bavarian/German, Jews of this wave of immigration looked down on less assimilated Jews, especially waves of immigrant Jews from Eastern Europe. Though I have discovered little that would indicate my great-grandparents’ feelings on the subject of being Jewish, I see that long before the Christmas celebrations I remember from my childhood, my grandparents and their children, my mother and uncle, also celebrated Christmas.[slide 24] I know my mother identified with her upper-middle class German Jewish relatives, and I’d never met any relative who knew Yiddish. I never heard their voices and have no idea of how much of a German or Yiddish cadence and accent these voices may have had, but the little wallet that had held the newspaper clipping yielded another surprise – a letter Henrietta had written in Yiddish.

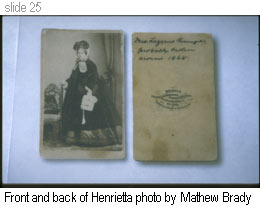

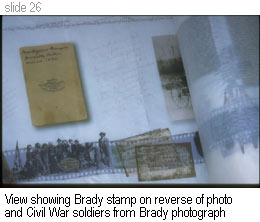

Because of my interest in the lines that hold public stories and my family stories in parallel, I’m also intrigued by indications of connections to the U.S. history of the very time in which my great-grandmother constructed this album, the era of the U.S. Civil War. [slide 25] The back of one photo of Henrietta shows that the studio of Matthew Brady took the photo, and many readers/viewers will know Brady as the famed Civil War photographer. While I was engaged in the making of “Reel Family,” I had to wonder if any relatives of mine [slide 26] were involved in slavekeeping. I learned from reading that Jews (who were not typically landowners but, more usually, merchants) were seldom slaveowners but that some Jewish merchants were associated with the selling of slaves. [slide 27] I included in “Reel Family” two business cards with names of Rosenfeld family members. I know nothing of the relation of these two Richmond,Virginia dry goods merchants and family members to slavetrading but placed the cards in “Reel Family” to raise questions.

My mother’s immediate family’s story is one marked at least as much by attributes of (upper) class life as by any embrace of Jewish customs or ways of life.[slide 28] [slide 29] (Upper class life ended in my mother’s generation with my father’s business financial reversals in the 1950s.) The scroll continues along its 22-foot length, [slide 30] sometimes giving visual emphasis to the very act of photographic recording through the pictures of still and motion picture cameras that appear repeatedly along the length of the scroll.

As the scroll continues to unroll toward its ending at the right, the parallel themes of scroll and film carry forward. I added gold illumination throughout “Reel Family,” as the detail in the illustration [slide 31] makes clear. It’s in the delicate illumination that the scroll most clearly, perhaps, takes on references to medieval scrolls and other medieval illuminated Jewish manuscripts.

The story in the scroll moves in pictures from the 1860s carte de visite formal portraits typical of the day and age when Henrietta started the album to more informal views discovered at my aunt’s from later years. One such later picture [slide 32] shows a family outing in 1905. My mother is the baby and the outing depicted may have been the Fourth of July. What is interesting to me is that the back of the photo has a handwritten list of those in the photo. From this list of names I know that later generations from the Seligman family are among the adults standing at the side of the auto waving American flags.

I ended the scroll with the family tree [slide 33] [slide 34] as it allowed me to insinuate myself into the long saga, if only by name. By way of the family tree, I even stretch the story forward one generation, to my daughter, Julia, whose name also appears here.

Though the scroll “Reel Family” is done, I don’t feel “finished” with a number of the explorations I have begun. Already I am at work on the parallel piece I mentioned as I began this essay, the one based on the album my father’s mother, Flora, started at the time my father left Nazi Germany for America in 1933. As with “Reel Family,” the piece in progress also unfolds parallel stories of family, immigration and anti-Semitism. My current project continues my exploration of the Jewish aspects of my family’s stories and of the complex weave of private moments bound up in public histories that are intrinsic to family albums.