The Human

If we turn to the human, what will we find? As an intervention into the scholarship on humans, machines, and animals, Sylvia Wynter submits that the human was congealed through inhuman racial conquest and denigration. Wynter is expressly interested in race, and her argument centers on the colonial encounter as a way for the West to configure the “descriptive statement of the human.” 1 In particular, Wynter shows how the human was not only a racialized subject utilized to separate Africans and Native Americans from Europeans and Euro-Americans, and thereby to justify the colonial conquest, but that it also was “overrepresented” as “Man.” Wynter argues that Western imperialism

thereby [came] to invent, label, and institutionalize the indigenous peoples of the Americas as well as the transported enslaved Black Africans as the physical referent of the projected irrational/subrational Human Other to its civic-humanist, rational self-conception. The West would therefore remain unable, from then on, to conceive of an Other to what it calls human—an Other, therefore, to its correlated postulates of power, truth, freedom. All other modes of being human would instead have to be seen not as the alternative modes of being human that they are “out there,” but adaptively, as the lack of the West’s ontologically absolute self-description. 2

“As Wynter describes, the Western idea of the human was a project that instituted indigenous peoples and Black Africans as Human Others. The Other could never fit the description of the human. The process of inventing and institutionalizing indigenous and enslaved Black Africans was a process that had to maintain a certain logic of the “human.”

However, despite all her interventions, Wynter does not build on the human/animal analytic or the relation of the human to machines. She cites Gregory Bateson, a key figure in the theory of cybernetics, but she does not mention cybernetics herself. Wynter does include a brief mention of “Asian subjugation,” and it is this juncture that connects Wynter’s scholarship with further repairing theories of the human and racialization that build upon the study of the human/machine/animal encounter. 3

How We Became (Post)human

If Wynter’s explication of colonialism’s role in the creation of the liberal human subject as Man was a critical intervention in the philosophical discourses of the human, the emergence of the posthuman and the cyborg, the fusing of human and machine, prompts further questions on issues of race, gender, and difference. Theoretical discourses of the posthuman and cyborg emerged in the 1990s with monographs and scholarly essays published into the present, by science and technology studies scholars such as Lucy Suchman, Donna Haraway, N. Katherine Hayles, Ronald Kline, and Cary Wolfe. 4 In his book What Is Posthumanism?, Wolfe traces how the term “posthumanism” worked itself into the humanities and social sciences during the mid-1990s, although the term actually goes back to Michel Foucault’s articulation of the human.

Unlike previous philosophical work on the relations between human and machine as discrete entities, the many varieties of posthumanism have in common a concern with the transgression between the human and machine. Hayles writes, “although the posthuman differs in its articulations, a common theme is the union of the human with the intelligent machine,” and “the posthuman view configures human being so that it can be seamlessly articulated with intelligent machines. In the posthuman, there are no essential differences or absolute demarcations between bodily existence and computer simulation, cybernetic mechanism and biological organisms, robot teleology and human goals.” 5 Haraway formatively centered a feminist critique of the human/machine analytic based on the cyborg. Haraway writes, “The cyborg appears in myth precisely where the boundary between human and animal is transgressed”—it is a “theorized and fabricated [hybrid] of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.” 6

In the move to the posthuman, theorists critique the notion of the liberal human subject through analysis of gender (although some varieties, such as transhumanism, may uphold the liberal human subject and elide gender). For example, Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” published in 1983, formatively transformed feminist critique in her theorization of the cyborg, and Hayles theorized the gender and sexuality of the Turing Test in her introduction to the posthuman. While Haraway in particular figures in women of color analysis in her “cyborg manifesto,” further theorization involving racialization and the cyborg should be added to this scholarship to build on the insightful attention that Haraway, Hayles, and other scholars have paid to the intersectional gender politics of the human/machine analytic.

I find my robot most in queer and feminist theorist Jasbir Puar’s response to the debates between intersectionality and assemblages; her critique provides vital insights and provocations. In her essay “‘I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess’: Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory,” Puar argues that assemblage theory (informed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari) and intersectional theory (informed by Kimberlé Crenshaw) should not be oppositional theoretical paradigms, but “frictional.” Puar’s large project utilizes assemblages as “relations of patterns” however she notes that amongst many definitions, she is being more interested in “what assemblages do.” 7 For our purposes in this search, I want to focus on—in what Puar offers as one example in a list of assemblage interventions—“Assemblages do not privilege bodies as human, nor as residing within a human/animal binary.” 8 Puar contends the usefulness and necessity of intersectionality, noting however that intersectionality oftentimes elides other axes of difference, such as sexuality, with its focus on race. Intersectionality can also, according to Puar and other theorists, perpetuate the reification of women of color as perpetual subjects of difference. Moreover, Puar offers that the “dominant feminist method” of intersectionality may prompt characterizations of other methods, such as “assemblage,” as “problematic.” 9 Inspired by Puar’s articulation, when searching, a project on race and robots requires intersectionality and other frames.

For Puar, posthumanist feminist scholars offer differing accounts of the subject because the “liminality of bodily matter cannot be captured by intersectional subject positioning.” Puar positions science and technology scholars such as Haraway and Barad as posthumanist and theorists of assemblages in the juxtaposition of intersectionality and assemblages. Central to Puar’s claim is a return to Haraway and the “cyborg” or “goddess.” She writes:

To return to the title of this piece, and the juxtaposition that Haraway (unfortunately, but presciently) renders, would I really rather be a cyborg than a goddess? The former hails the future in a teleological technological determinism—culture—that seems not only over determined, but also exceptionalizes our current technologies. The latter—nature—is embedded in the racialized matriarchal mythos of feminist reclamation narratives. 10

Puar opts to choose a cyborgian cyborg; although she still asks if a cyborg-goddess is possible. Like much of women of color critique, Puar posits the importance of both intersectional and assemblage theory and makes a critical intervention within posthumanism. Posthumanist scholars do not examine the body for racial differences and the marks of stratification; these are the concerns of racial theorists. For the posthumanist scholar, what is of concern is when information loses its body, and the stakes of embodiment in the posthuman. 11 Is a cyborg-goddess possible? Indeed, Puar offers an important theoretical development in the study of racialization, and also highlights the gaping differences between posthumanist scholars and scholars of representation. Like Puar, I ask for a “frictional” relationship with racial theory and posthuman theorization.

Re-returning to Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto”

“The nimble fingers of ‘Oriental’ women…

Ironically, it might be the unnatural cyborg women making chips in Asia and spiral dancing in Santa Rita jail whose constructed unities will guide effective oppositional strategies.”

—Haraway 12

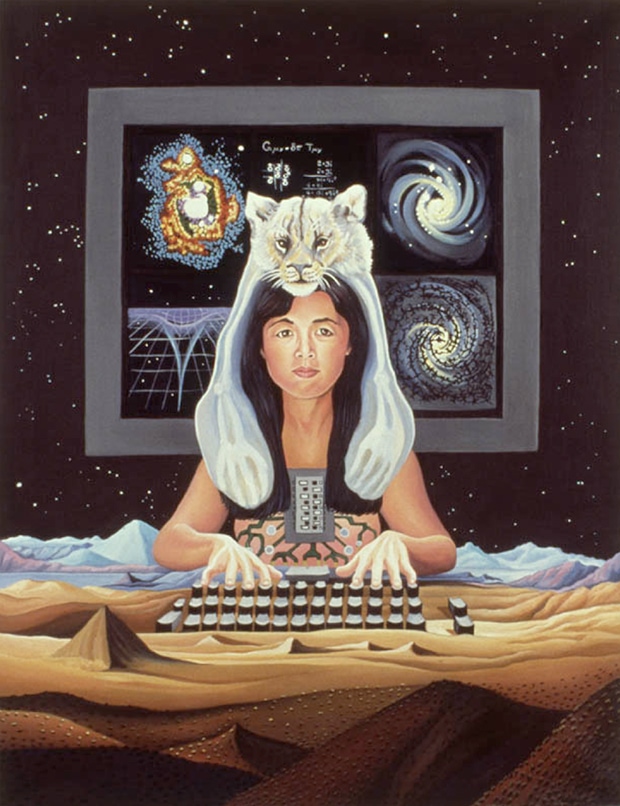

Per Puar’s analysis, I re-return to Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto,” to find more specifically traces of the Asian and Asian American and/as robot. I find two lines that evoke this dialectical connection between Asian and/as automaton. In Haraway’s essay, she is laboring, the close connection of the historical connotations of the robot as such. Yet what is the parallel between the women spiral dancing in the Santa Rita jail and the cyborg women making chips? Nimble fingers. Various scholars have critiqued Haraway’s conflation of these two groups of women as cyborg. 13 Additionally, Haraway has since revised her position in regards to including both groups of women—spiral dancing feminists and Asian women laborers—conflated both as “we” and equal proximity to the cyborg. 14 However, I want to turn to the cover image painting of Haraway’s Simians, Cyborgs, and Women by Lynn Randolph.

In particular, I point to the artist’s statement about the painting, which she says was inspired directly by lines from the manifesto. As Randolph writes: “Haraway’s description of Asian women with nimble fingers, working in enterprise zones for very little remuneration stuck in my head. I had recently met a young Chinese woman, Grace Li, who was one of my late husband’s sociology students at the University of Houston… I asked Grace if she would pose for me and she agreed.” 15

I argue elsewhere, in my analysis of the 1960s robotic art of new media artist Nam June Paik, that Asian American artists deploy a strategy of what I call “racial recalibration”—a racial formation that occurs through aesthetic tinkering, hacking, and recreating with emergent technologies that re-wires racial knowledge of the Asian and Asian American as robot. 16 I want to extend this analysis of recalibration to consider how the painting of Haraway’s cyborg offers us a dialectical connection between the machine and Asian/Asian American.

The painting includes said model Grace Li, in the center, typing on a keyboard, with the computer board on her chest and a backdrop of various scientific and computer activities hanging like an artwork behind her. It is a science fictional rendering of another world. The Asian cyborg feminist here is kin with animals: a tiger headdress rests atop her head, the skeleton of the animal visible and lightened. Above are a galaxy of stars, while below are sand dunes, and it does seem like this cyborg-goddess is ruling the world. Randolph elaborates on her painting: “I put the DIPswitches of the computer board on her chest as if it were a part of her dress. A giant keyboard sits in front of her and her hands are poised to play with the cosmos, words, games, images, and unlimited interactions and activities. She can do anything.” 17

“She can do anything”: Randolph transforms the Asian woman worker into a science fictional cyborg that utilizes technological access for her own agentic activities. Randolph emphasizes that both the Asian cyborg-goddess and the tiger “look directly at the viewer.” She writes: “The underlying intent was to create a figure that could visually do what Haraway was describing as the potential for re-figuring our consciousness.” 18 In considering the historical materiality of gendered racialization that are crucial to its articulation and, as Barad writes, re-turning to the image from Haraway, to reread again, and to see the racial potential through which we can also see diffraction, the light.

Conclusion: Theory as Technology

In discussing science and technology studies, Charis Thompson points out that fields such as queer, race, and ethnic studies came to STS much later than fields such as the study of scientific knowledge (SSK, 1970s) and actor network theory (ANT, 1980s), “but they interact vigorously with them, while adding new areas of focus and new analytic resources.” 19 Understanding how, as Thompson writes, race, and gender, and sexuality, and disability, and various other axes meet helps me understand where to find my robot, and the challenges to finding her. Models written by Thompson, Puar, and others create the theoretical technologies that offers multiple locations for analysis. Scholarly writing can often alienate people of color, queer people, and women, and the study of technology often excludes minority participation. As race must be theoretized within a science and technology studies lens, theory can also be understood in a similar way through the technological. And in doing so, we can add “new areas of focus” such as the analytic of race and Puar’s “Cyborg-Goddess.” 20 Like Thompson, Lisa Nakamura rereads the late African American feminist scholar Barbara Christian and echoes her disciplinary concerns; in Nakamura’s words, Christian “asserts the technology of literary theory was made deliberately mystifying and dense to exclude minority participation.” 21 Citing theory as technology, Nakamura’s reading of Christian recognizes that scholarship is also technological and can be utilized for resistance. In Cybertypes, Nakamura writes about how critical theory works as “a technology or a machine that produces a particular kind of discourse.” 22

If theory and academic writing are a “machine” or a “technology,” I hope for more technologies for the social good. In acknowledging intellectual debts, we can understand that neither technology nor theory emerge from a void. Is it our work, then, not simply to introduce correctives to existing theory, but to push forward, to seek theoretical frameworks that make Haraway’s and Randolph’s Asian feminist cyborg more than a figure of science fiction, but a feminist STS reality? We should seek theories that “interact vigorously” with one another, frictionally, in which boundaries “bleed,” and in order to build a world that is “far from disheartening.” 23 At the theoretical gaps, and frictions, is where solder melts and sediments/there, at the intersections of boundaries and de-wires/re-wires/I realize I find traces of her.

Acknowledgements: I thank Patrick Keilty, Tami Navarro, and Leslie Regan Shade for their vital editorial guidance and the kind invitation to submit; Beth Jacobs, Alison Osworth, Hope Dector, and the S&F Online anonymous reviewers for their feedback on the revision process; An early version of this article was shaped by formative comments and mentorship from Keith Feldman, Ken Goldberg, Charis Thompson, King-Kok Cheung, and Evelyn Nakano Glenn. With gratitude to Lynn Randolph for her permission to republish Cyborg. At the University of Oregon, Joan Haran pointed me in the direction of Karen Barad’s diffraction, and undergraduate research assistant Rachel Voigt provided support on the citations.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 281.[↑]

- Ibid., 282.[↑]

- Ibid., 267.[↑]

- Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1990); N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Ronald Kline, “Where Are the Cyborgs in Cybernetics?,” Social Studies of Science 39 (2009): 331.[↑]

- Hayles, How We Became Posthuman, 3.[↑]

- Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, 152.[↑]

- Jasbir K. Puar, “‘I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess’: Becoming-Intersectional of Assemblage Theory,” PhiloSOPHIA: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 2, no. 1 (2012): 49–66.[↑]

- Ibid. 49–66.[↑]

- Ibid. 49–66.[↑]

- Ibid. 49–66.[↑]

- Hayles, How We Became Posthuman, 3.[↑]

- Haraway, 178. [↑]

- Jeffrey A. Ow, “The Revenge of the Yellow Faced Terminator: The Rape of Digital Geishas and the Colonization of Cyber Coolies in 3D Realms’ Shadow Warrior.” in Asian America.Net: Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Cyberspace edited by Sau-ling Wong and Rachel Lee; (New York, Routledge, 2003) 250.[↑]

- Constance Penley, Andrew Ross and Donna Haraway, “Cyborgs At Large, Interview with Donna Haraway.” Social Text No. 25/26 (1990): 17.[↑]

- Lynn Randolph, “Modest Witness: A Painter’s Collaboration with Donna Haraway,” 2009, available at the artist’s website.[↑]

- Rhee, Ibid.[↑]

- Randolph, “Modest Witness.” Emphasis mine.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Charis Thompson, Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Artificial Reproductive Technologies, (Cambridge: MIT, 2005), 49.[↑]

- Lisa Nakamura, Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (London: Routledge, 2002), 8.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid., 3.[↑]

- Lisa Nakamura, Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 208.[↑]