*Reprinted with the permission of The Nation.

The morning after I returned to Chicago from the recent Margaret Mead Legacy conference at Barnard College, honoring the centenary of the anthropologist’s birth, a newspaper columnist rang me at dawn with the demand that I explain “from a feminist perspective” why Tony Soprano is “this millennium’s first sex symbol.” “Does this mean that we’re all going backwards?” she asked with relish. Dumbfounded, I countered, rather crankily, with the request that she give me evidence that any women anywhere were claiming sexual attraction to a dumb, sexist and racist, unfaithful, badly out of shape, psychologically damaged organized crime capo. (Not that I don’t love the show; who doesn’t, even if I have to watch my own people get minstrelized to a fare-thee-well.) Nothing daunted, and with not a shred of shame that she in fact had no evidence, the columnist cleverly countered, “Well, if it were true, what would your feminist perspective be?” As Rayna Rapp of the New School had declared to the amused Barnard audience, I had that feminist anthropologist’s “WWMMS moment”: What Would Margaret Mead Say?

What would she say? We could easily remark about Mead what Walt Whitman, another New York-based celebrity, claimed of himself: She is large, she contains multitudes. Mead was professionally active for fully half of the last century and, by choice and her own never-ending efforts, very much a public voice for most of that time. She said a lot of different things in different decades, and she was received variously by her own professional colleagues and within a shifting American public sphere. The Barnard conferees, including the college President, Judith Shapiro, herself a feminist anthropologist, and Mead’s daughter Mary Catherine

Bateson, spoke on key aspects of Mead’s work, on the ways in which she had inspired their own research, and on what her legacy might be in this millennium. They agreed that she and her cohort made a series of novel connections: envisioning the malleability of gender relations, seeing human corporeality, ritual and psychology as one, emphasizing the deeply enculturated nature of child-rearing and of adolescent coming of age. Elaine Charnov, director of the Margaret Mead Film Festival, and Faye Ginsburg; of New York University both spoke as well of Mead’s prescience in the use of ethnographic film and her general status as technological pioneer.

“But there is no Margaret Mead now,” the panelists lamented with the partisan, largely female audience crowding the auditorium, and variously attributed that fact to her heroic uniqueness, to her intellectual coming of age being the “right time and the right place” for public sphere presence, to the rise of the New Right in the West and the triumph of global neoliberalism, to the renaissance of biological reductionism in the overwhelming American popular-cultural presence of sociobiology, to our collective retreat from public voice.

Mead became a popular icon over the course of the 1960s, and attained the status of Holy Woman in her last years, as the late Roy Rappaport commented (she died in 1978). And it is difficult to evaluate Holy Women, particularly in the long wake of a posthumous attack – by the Australian anthropologist Derek Freeman, in 1983 – that quickly became a mass media firestorm. Margaret Mead and Samoa is a badly written and unconvincing claim that Mead, influenced in a “culturally determinist” direction by her nefarious adviser Franz Boas, falsely interpreted the Hobbesian world in which Samoan youth came of age as a gentle idyll. Freeman claimed that the true Samoa is characterized by a “primeval rank system” that dictates a “regime of physical punishment” of children and violent “rivalrous aggression” among men, “highly emotional and impulsive behavior that is animal-like in its ferocity” among chiefs, and a rape rate “among the highest to be found anywhere in the world.” Scholars criticized Freeman’s theoretical vacuity and empirical flaws, his ahistorical claim of an Eternal Samoa, his failure to realize that his key informants – older, high-status males – were no more a “true and accurate lens” of Samoan culture than were Mead’s young female companions. Most especially, feminists noted the rank sexism of Freeman’s focus on Mead’s youth and size: The “liberated young American . . . only twenty-three years of age…[was] smaller in stature than some of the girls she was studying.”

But public reception of, as opposed to in-house reaction to, Freeman’s book was most importantly about the extraordinary fit between his line of attack and newly dominant New Rightist politics. Margaret Mead and Samoa provided a Heaven-sent opportunity for the press to rant against the “liberal feminist culture” and “lifestyle experiments” with which it newly identified Mead, conveniently forgetting its fervent eulogies of her of only half a decade earlier. As the late David Schneider noted at the time, Freeman’s book was “a work that celebrate[d] a particular political climate by denigrating another.” Freeman’s vision, at one fell swoop, allowed commentators to deny female intellectual capacities across all societies; to naturalize male dominance, male sexual violence and aggression; and at the same time, to slur Samoans – and with them all so-called primitives, that is, all people of color – as violent, nasty savages. Logically self-contradictory and empirically bankrupt though it was, Freeman’s narrative was wonderfully composed to fit American Reagan-era contentions of the foolishness of the movements of the 1960s and 1970s, as you “can’t change human nature,” and Western, upper-class, male, heterosexual, and white dominance are natural after all.

Freeman’s frisson in popular culture is now long past, victim of the increasingly rapid biodegradation of American popular consciousness. I routinely ask gender studies and anthropology classes if they have heard of Freeman or his book, and very few respond affirmatively, even when they have a niggling sense that there is some sort of blot on Mead’s reputation. Only American New Rightists remember and believe in Freeman’s attack on Mead: A Lexis/Nexis search for all articles referring to the two since 1990 revealed only a handful of sneering articles in rightist outlets, whereas a general search using Mead’s name alone garnered thousands of “hits.”

But while specific media scandals always fade, popular-cultural troping of anthropology and anthropologists is unceasing, and distorts whatever information members of the discipline may have to offer considering power and culture in human societies. The issue is more crucial than is often realized, because popular apprehensions of anthropology and anthropologists are importantly interwoven with changing American constructions of Others – those deemed somehow apart from the norm by virtue of race, gender, nationality, class, religion, sexual identity. “Culture” and “biology” are the two key domains through which Americans historically have laundered politics from public sphere inspection. And anthropology, sententiously self-described as the most humanistic of the sciences, the most scientific of the humanities, has thus evolved into a cynosure of political approbation and attack, both refuge and refuse in contemporary contestations over power.

II.

I have recently identified a series of anthropological “Halloween costumes” into which, since the 1960s, American popular writing, film, television, cartoons and advertising have tended to squeeze all anthropological knowledge. Each costume – Technicians of the Sacred, Last Macho Raiders, Evil Imperialist Anthropologists, Barbarians at the Gates and Human Nature Experts – reflects minor strands in some past or present anthropological writing. More important, each enacts a retrogressive politics with reference to culture and power on the U.S. and global stage. The costumes, in other words, act as Procrustean beds, amputating those pesky limbs of anthropological knowledge that flop outside their predetermined grids.

Technicians of the Sacred, for example, posits anthropologists as time travelers who bring back to us visions of Noble Savages living nonviolently and cooperatively, practicing sexual equality, respecting the environment and engaging in religious worship somehow more “spiritual” than ours. Such a seemingly benign vision, however, yanks contemporaneous populations out of our shared stream of world history and prevents us from understanding the ways in which they lack political power on local and global stages. Last Macho Raiders imagines anthropologists as a guild populated by cool Harrison Ford lookalikes, virile, positive imperialists. This particular Halloween costume has long had little appeal to most members of the guild but remains widely used in popular culture. The Evil Imperialist Anthropologist, on the other hand, who is simply a Last Macho Raider seen from the viewpoint of the Raided, has roots in some Third World and Native American writing of the 1960s, became a stock postmodern character in much academic writing in the 1980s and spilled over into popular culture. Barbarians at the Gates envisions anthropologists as foolish multiculturalists, misguided salespeople hawking inferior-non-Western-cultural materials to a gullible American public. In other words, it is a rightist, racist framing of the Technicians of the Sacred trope, and has been heavily purveyed in New Rightist writing through our recent culture wars. And Human Nature Experts paints anthropologists as pure scientists-gatherers of facts alone. Of course we need to stand for empirical reality, but this particular trope functions in the public sphere today almost solely as a rationale for sociobiological arguments, as if all fact and logic were the sacred possession of that contemporary version of biological reductionism alone, and the active armies of distinguished anti-sociobiology scientists were a mere rumor in the wind.

We might say, then, that Freeman, in an act of simultaneous attack and self-aggrandizement, dressed Mead as a Barbarian at the Gates and himself as a Human Nature Expert. Ironically, though, Mead herself, over the decades, had no small hand in the fashioning of the Human Nature Expert costume. At the same time, the Halloween costumes are most definitely not unisex, and Mead, like the rest of us, never escaped her gender. Looping back to the years of Mead’s intellectual coming of age and first writing helps us to trace the changing lineaments of “culture” in American politics, particularly that shifting overlap of gender and race that is so crucial to the framing of rationales for and protests against contemporary lines of stratification.

III.

In the 1920s, counter to the assertions and interpretations of more recent commentators, Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa was written, and was read, not as a paean to free love or women’s rights or even the romantic lives of “noble savages,” but rather as a scientific account of certain differing cultural features in a “more simple” society that “we,” meaning middle-class white Americans, might wish to adopt in order to raise “our youth” in a less stressful manner. Mead defined herself early on, as I have written, as an objective scientist, a professional social engineer. Despite her sometimes somewhat overblown lyricism – “A group of youths may dance for the pleasure of some visiting maiden,” “lovers slip home from trysts beneath the palm trees” – Mead ultimately is no Technician of the Sacred, no romantic antimodernist. Her 1920s Samoa is a “shallow society” where “no one plays for very high stakes,” of use to “us” as an object of scientific study: it is a “human experiment” under “controlled conditions.”

While Mead worked almost solely with girls and women, and certainly wrote, as a contemporary reviewer put it, with the “clean, clear frankness of the scientist” about their sexual experiences, she did not draw explicitly feminist lessons from her fieldwork. Like many young women of her postsuffrage era, to whom feminism seemed both passé and potentially professionally damaging, Mead took advantage of the doors opened by the women’s rights activism of her mother’s and grandmother’s generation (and indeed, by her own mother and grandmother) but did not herself join that ongoing movement. Nancy Lutkehaus of USC pointed out at the conference that Mead became a public intellectual in the 1920s because of her fortuitously advantageous position in time and space: based in New York, writing about the South Seas at a point when that region had caught the American public imagination, and indeed at just the point that newspapers and magazines were proliferating across the American landscape. And, I would add, because she wrote then not as a radical but as a modernist, advocating changes for the white middle classes – coeducation, less authoritarian childrearing, greater frankness about the facts of birth, reproduction, and death – already in the works in the Roaring Twenties.

But scientist or not, Mead was at times portrayed in the press as many anthropologists, especially female anthropologists, have been since: with a certain condescending, inappropriately sexualizing humor, identified with her inevitably stigmatized subjects. Lutkehaus has unearthed 1920s newspaper stories claiming that Mead went to Samoa to study the “origins of the flapper.” And in the 1930s, a popular magazine coyly described Mead as “a slender, comely girl who danced her way into the understanding of the Melanesian people and became an adopted daughter and a sort of princess of the Samoans. When they anointed her with palm oil and indicated that a dance was in order, she did a nice hula and they declared her in – indicating the adaptability of the modern young woman if she just has a chance to step out.”

It was one of the first steps on the long road toward my

Sopranos interlocutor – herself, as we shall see, merely part of a vast contemporary phenomenon.

IV.

Mead’s early anthropological work reflected both developing British and American concerns: She did careful kinship and social organizational research in Samoa and New Guinea, and studied what she construed to be varying cultural temperaments – characteristic psychological states – and their connections to sex roles and life cycles. But by 1935, when she published the widely read Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, her analytic twig was permanently bent in the Americanist psychological, “culture and personality” direction. Sex and Temperament, rather than Coming of Age, is the work in which Mead makes her clearest arguments concerning the plasticity of human sex role arrangements: “Many, if not all, of the personality traits that we have called masculine or feminine are as lightly linked to sex as are the clothing, the manners, and the form of head-dress that a society at a given period assigns to either sex. . .. We are forced to conclude that human nature is almost unbelievably malleable.”

This is the modal Mead, the ur-popular culture anthropologist who was rediscovered by Second Wave feminists, assigned all over the academy and read aloud in consciousness-raising groups in the 1970s. It is important to remember, though, that every generation reads selectively. Mead’s “gender malleability” statements are, in fact, lodged inside a larger argument against women’s equal rights as represented by the contemporary Soviet Union. Mead saw in the opening of all occupations to women there a “sacrifice in complexity” of culture: “The removal of all legal and economic barriers against women’s participating in the world on an equal footing with men may be in itself a standardizing move towards the wholesale stamping-out of the diversity of attitudes that is such a dearly bought product of civilization.”

Ironically, the very popular troping of anthropology for political purposes has contributed to the discipline’s unpolitical reputation. Explicitly political statements in anthropological texts vanish in the course of reading, the discipline’s pioneering anti-racism and near-implosion over Vietnam have succumbed to the culture of forgetting, and the long-vital left tradition in anthropology worldwide is popularly and often even professionally invisible. When I gave an early talk on Mead for a group of women’s studies professors, a senior political scientist exclaimed afterward that she was surprised to learn that Mead “had any politics.” All God’s anthropologists got politics, most especially the very public Margaret Mead.

Those politics varied considerably over the long decades of Depression, war, decolonization and cold war, and the 1960s and 1970s conjuncture of Vietnam, civil rights, the Second Wave of feminism and associated gay rights organizing. The one common thread across the decades, though, was Mead’s adherence to Progressive social engineering, and thus her profound commitment to the notion of disinterested science and the rule of experts. In terms of gender, from the 1930s until the early 1970s, when she did take on a liberal feminist stance, Mead embraced the conservative Freudian notion of the universal “constructive receptivity of the female and the vigorous outgoing constructive activity of the male.” While Mead continued to argue against isolated, narrow nuclear families, and for careers for better-off women as long as they were “womanly” both at home and at work, it is no wonder that Betty Friedan in 1961 spent almost an entire chapter of her celebrated book attacking Mead’s pernicious “super saleswomanship” of the Feminine Mystique. It is equally unsurprising that Second Wave feminists, in rediscovering both Friedan and Mead for their own purposes, read Friedan as selectively as they (we) did Mead.

Similarly, Mead’s war work for the American government extended into both her very successful postwar advocacy of federal funding for anthropological research and her cold warrior stance against, among other actions, antinuclear and anti-Vietnam War protests. (The latter issue led to a huge fight at the 1971 American Anthropological Association meetings, during which Mead was hissed by an antiwar audience of 700.) These political actions were overwhelmed, in popular culture, by Mead’s highly public approbation of “questing youth” from the mid-1960s forward, and the liberal feminist alliances of her last years. She even had her own character in the first stage version of Hair, who celebrated male “long hair and other flamboyant affectations,” and whose song ended in the recitative, “Kids, be whatever you are, do whatever you do, just so long as you don’t hurt anybody.”

V.

Hair‘s sendup of Mead followed her thinly disguised appearance as a famous older female anthropologist in Irving Wallace’s sleazy 1963 potboiler, The Three Sirens: “She thought of the place: the temperate trade winds, the tall, sinewy, bronze people, the oral legends, the orgiastic rites.” The sexual imputations in both texts return us to consideration of my morning journalist and Tony Soprano. Like all occupational groups, anthropologists have traditions of internal self-reference, but ours have intersected in particularly damaging ways with the changing Zeitgeist. From Clyde Kluckhohn’s 1940s boast that we were all “eccentrics” “interested in bizarre things,” to Clifford Geertz’s 1984 reference to anthropologists as “merchants of astonishment,” many of us have enjoyed exoticizing ourselves, playing, as I have written, the court jesters of academe. While some of this self-exoticization has always arisen from identification with oppressed populations, the overall effect of the court jester construction is dire. Anthropologists have become the American public’s “exotics at home,” identified with our demonized, trivialized subjects, or rather, those who are presumed to be our sole subjects – non-Westerners around the globe, the poor, the nonwhite, and sexual minorities in every country. And, of course, in double irony, the numbers of nonwhite, non-Western and/or gay anthropologists, never insignificant, grow larger every year. By a process of infinite recursion, the stigmatized figurings of subjects and researchers repeatedly rub off on one another, denying dignity, history and human rights to domestic and foreign “exotics,” and stripping anthropologists of the intellectual authority with which to contribute to progressive politics.

Ironically, the “exotics at home” complex also reifies the discipline’s long historical game of peekaboo with Americanist research. Mead’s own master’s thesis concerned the link between exposure to English and IQ test results among Italian-American schoolchildren in New Jersey (Tony and Carmela’s grandparents!), and significant numbers of anthropologists have done United States fieldwork in every decade since. All of the Barnard conference senior panelists, for example, are engaged in Americanist research. But in the grand adaptive radiation of disciplinary institutionalization as American universities grew over the twentieth century, anthropology was defined in contradistinction to sociology as the study of non-Westerners (and based on ethnographic rather than quantitative methodology), perpetrating falsehoods about actual work being done in both fields. Since at least the 1940s, anthropologists and middlebrow media have repeatedly “discovered” that anthropology is “just now coming home.” In 1974 Time declared that

the gimmick is that anthropologists, after decades of following Margaret Mead to Samoa and Bronislaw Malinowski to the Trobriand Islands, have staked out new territory…. U.S. anthropology, it seems, must recognize that the primary tribe to study is the Americans.

But then, fifteen years later, the New York Times Book

Review declared:

Pity the poor anthropologist. She has trekked the highlands, machetied the jungles, sifted the sands for new tribes to study. But the Ik have been exposed, the Tasaday tallied. What’s left? Increasingly, today’s would-be Meads and Benedicts are turning in their bush jackets for tweeds, for some easy poking around in their own backyards–where, lo and behold, they unearth practices as alien to Western norms as any found in the heart of New Guinea.

And so it goes. While such consistent failure to engage with empirical reality, and the condescending notion that U.S. fieldwork must of necessity be merely “easy poking around,” are extremely annoying to those of us who have done arduous research in American settings, I want to make a different point. That is, the culture of forgetting involved here enacts what I have labeled the anthropological gambit, or the pseudo-profound claim that “we” are like “primitives.” The attribution of “our” characteristics to “them,” and vice versa, is always good for a laugh in popular culture. “We” are only the Ik, the Tasaday, the Trobrianders. An X is only a Y.

As if to prove the point, the day before I left for the Barnard conference, the New York Times happily declared that “some distant day, anthropologists may discover what was surely the tribal art of 20th century American suburbia: paint-by-number paintings.”

There is nothing innately wrong with cuteness – it is after all a matter of taste. The point, though, is that the gambit, which is ubiquitous in the public sphere, is inherently political, engages in hidden rhetorical work. It certainly represents Edward Sapir’s “destructive analysis of the familiar,” one element of a liberatory cultural critique in use in the West at least since Michel de Montaigne’s ironized cannibals. But it does so in a profoundly ahistorical, noncontextual way, and so places Others at temporal distance to ourselves and effaces the questions of history and power on both poles of the contrast.

VI.

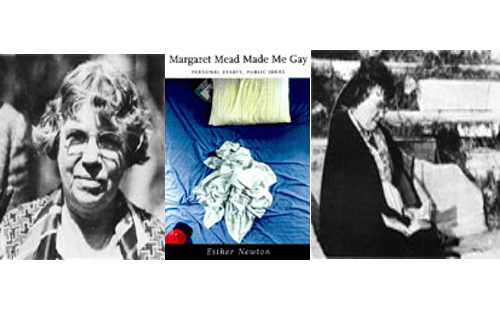

Finally, anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict pioneered an open-minded consideration of the varieties of cross-cultural human sexuality. Esther Newton, who recently published a memoir magnificently titled Margaret Mead Made Me Gay, spoke compellingly at the conference on the impact of her adolescent reading of Mead’s “defense of cultural and temperamental difference.” But that reputation for sexual frankness, combined with femaleness, the anthropological gambit and exoticism at home, has also long made women anthropologists, as I have noted for Margaret Mead, vulnerable to sexually insinuating popular-cultural costuming. In the rollicking postwar musical and film On the Town, recently revived on Broadway, a sex-crazed debutante “anthropology student” character throws herself at one of the sailors on leave because he “exactly resembles Pithecanthropus erectus, a man extinct since six million BC.” The television series 90210 had a sluttish “feminist anthropologist” character, and Sarah Jessica Parker, in Sex and the City, calls herself a “sexual anthropologist.” The way things seem to be going, we might want to specify another media Halloween costume for the feminist anthropologist: bustier and fishnets.

Feminist anthropologists tend to be a pretty tough bunch and certainly can take care of ourselves. (One of the conference participants pointed out to me with great glee that she was wearing fishnet hose.) The real issue is the one with which I began: the deadly intersection of the distorting Halloween costumes, the anthropological gambit and garden-variety sexism in the public sphere preventing the popular dissemination of actual knowledge on gender, culture and power. Consider my own experience. I write about gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, and class formation in the American past and present, particularly in American cities, and I have done popular writing on racial injustice (and its connections to gender) in the present. But when does the Fourth Estate contact me? Let’s just review instances from the past few years.

A 20/20 reporter called, wanting a professor to explain on-camera why “some men are sexually attracted to very obese women.” (He kept trying to assure me that the show “would not be sleazy.” Right.) A public radio show host invited me to do a Valentine’s Day show with her on love and courtship ritual. A local television newswoman wanted my “anthropological” analysis of why women were buying Wonderbras. A Newsweek reporter asked for my thoughts on why, despite so many decades of feminism, American women still enlisted the aids of hair dye, makeup, plastic surgery and diets. Didn’t that prove that we were genetically encoded to try to attract men to impregnate us and protect our offspring? A young stringer for Glamour called, looking for “expert” analysis of why women are attracted to certain types of men. An Essence reporter wanted my thoughts on why Afro-American women, according to her, repeatedly and irrationally fell for “thugs.” And last fall, a Good Morning America producer begged me to appear on a show with the theme “Is Infidelity Genetic?”

So I wasn’t entirely surprised by the Tony Soprano call, with its silly implications of a homogeneous feminism obsessed with mass media portrayals of sex roles. And I don’t think even the Whitmanesque Margaret Mead, today, would have an easier time of it. In her memorable last years, Mead could and did play the progressive Sibyl, the wise elder using her vast cross-cultural knowledge to comment favorably, to a largely adulatory press, on the increasing social liberalization that we saw around us. But that was before Jimmy Carter, with whom Mead was closely politically allied, lost disastrously to Ronald Reagan in 1980. It was before the New Right, before the race and gender backlashes of “the underclass” and “feminazis” and the internal problematics of identity politics, before the second, more successful rise of sociobiology, before the global rightward tilt and recent neoliberal triumph, before the corporate consolidation and increasing tabloidization of the media. And, of course, it was before the “turn to language” complexified the ways in which we all envision science, culture and knowledge.

We no longer unproblematically invoke “science,” but consider it a culturally contingent, powerful process. Emily Martin of Princeton and Rayna Rapp spoke at the conference about their ongoing and highly regarded research on gender in the production and consumption of scientific knowledge. But both scholars also work actively and even teach with bench scientists. Similarly, many of us work to reposition our analyses, no matter what their regional focus, both to reduce the United States and to enlarge it, always with the goal of accurately apprehending gender, culture, history and power. That is, we no longer simply observe the world from the perspective of the West, but instead consider the long regional and global histories of contact, trade, power politics, racial and ethnic formation and shifting political boundaries of which the United States and other Northern and Southern nations are part. At the same time, we no longer attempt to see the United States just as one among many nations – as in “an X is only a Y” – as it is still and has been the locus of global imperial power since the end of the Second World War.

These less Olympian, more nuanced understandings are a harder sell in the public sphere, but along with other progressives, we continue our Sisyphean engagement. And Mead’s image, although not entirely according to her intentions, continues to inspire radical visions of American and global potentials: of international understanding, of gender, race, class and sexual equalities, of a different, more egalitarian world. Marcyliena Morgan of UCLA, for example, reported that the hip-hop-involved adolescent Afro-American girls with whom she works see Mead as “a liberating force.” As Rayna Rapp ringingly concluded, “Collectively, we are surely on the case.”