December 12, 2013

University of Toronto

From the colloquia series “Feminist & Queer Approaches to Technoscience”

Some of the material in this transcript has since appeared in two other publications:

- Suchman, L. (2015). Situational Awareness: Deadly bioconvergence at the boundaries of bodies and machines. Media Tropes, V(1), 1-24.

- Suchman, L. (2016). Confinguring the Other: Sensing war through immersive simulation. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 2(1), 1-36.

Those of you who have been tracking the announcements for today’s talk will notice that the title has been a bit unstable, so let me begin by clarifying what I’ll be talking about today and how it tracks into the workshop tomorrow, which is titled “Configuring the human in technologies of virtuous war.” What I will do today is to sketch out the broader frame of theoretical and methodological commitments that informs my studies at the interface of the digital and other materialities, inspired by feminist science and technology studies. I will end today with an introduction to my current project on developments in contemporary war fighting, which we will then explore further in tomorrow’s workshop.

This image, which I will come back to, operates in the context of my title as a visual pun, but also as an indication of the kinds of relations that I’m interested in. So, entanglements of persons—there is a person off there, outside the frame; bodies, the one attached to this hand; and devices. It’s difficult to see, but she is actually holding a pen, with which she is highlighting an aspect of the computerized design rendering that she is describing. So we’re interested in technologies, discourses, and material practices, both inside and outside the frame. What I’ve given you is a particular screen capture from a video, which itself had already framed what it was that we were looking at in the research project from which this image is taken. And that question of framing, what is included and what is excluded, is going to be a recurring theme as we go along.

I used the word “entanglements,” so let me start with what feminist theorist Karen Barad says about entanglements. She says, quote, “To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in a joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence. Existence is not an individual affair. Individuals do not preexist their interactions; rather, individuals emerge through and as part of their entangled intra-relating” (2007: ix). So this is the slightly mind-bending conceptual frame that we are going to start with.

This quote comes from the book Meeting the Universe Halfway, published in 2007. In it, Barad develops this inversion of causalities, in which individuals are effects of, rather than prior to, their relations. And she at once works with and expands conceptual frames that are drawn from particle physics—she was a tenured professor of theoretical physics before she took up her current position as Professor of Feminist Studies, Philosophy, and History of Consciousness at the University of California at Santa Cruz. So she is bringing together theoretical physics, post-structuralist social theory, feminist theory, and science and technology studies to develop these ideas. The book elaborates a series of commitments and associated ideas. First of all, the inseparability of meaning and matter; that is, the inseparability of the conceptual or discursive and the material. Second, the question of how we might understand the capacities or the agencies of both humans and nonhumans as an effect of their relations. This is sometimes short-handed as the “more-than-human,” to reference the relation of humans and nonhuman animals to their environments, both the built and the natural. It is in our relations that our capacities for action emerge. And then, given this relational starting place, Barad asks how do we trace agential cuts, or the effects of the boundary work through which entities are constituted, including the inevitable exclusions that the cuts enact? So she is arguing that entities’ individualization is an effect of particular kinds of cuts in relations, and that those are things that we ourselves are implicated in. And one corollary of that is taking seriously the premise that the scientist is part of the world that she observes. As Barad argues, we are not outside of the world, nor are we in the world. We are part of the world’s becoming. One of my favorite quotes from the book is this one, “Agency is not an attribute, but the ongoing reconfiguring of the world (2007: 141).”

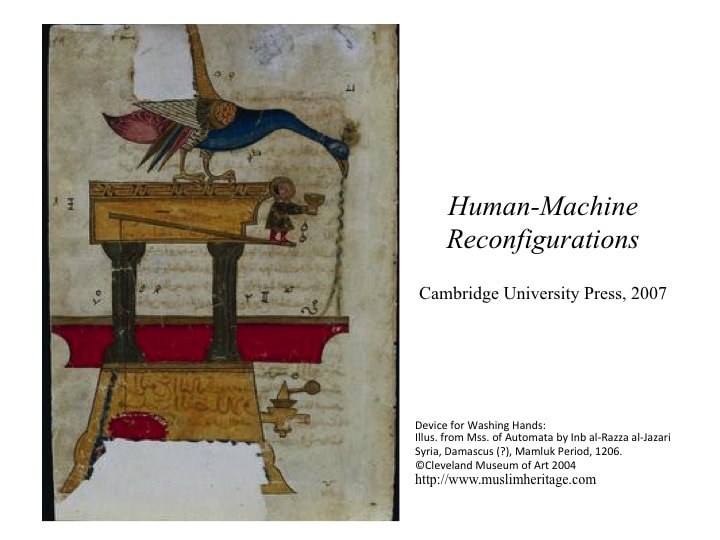

I’ve worked with this idea of reconfigurings myself most directly in thinking about relations between humans and artifacts, starting with my book Human–Machine Reconfigurations (2007).

This is the cover image from the book. It’s from a thirteenth-century manuscript of automata that were designed, or imagined—it’s not clear how many of these were actually realized—by the Arab scholar al-Jazari. And this particular automaton is titled A Device for Washing Hands. We have this device that configures a bird, a little human figure, and what are obviously built objects into a mechanism—this is clearly something that has been built—but where it is difficult to tell what is natural, what’s artificial, who’s doing what in the service of whom. So I like this figure because it is obviously a machine of some kind, but it is very ambiguous in its configuration in terms of the distributions between the humans and the nonhumans, and those are the questions that I explore in the book. My touchstone is the trope of reconfiguration, and at the center of which, literally, is the figure, and Donna Haraway’s argument that all language, including the most technical language, the most mathematical language, is figural, it’s metaphorical, it’s made up of tropes and turns of phrase that invoke different associations across diverse realms of meaning and practice (1997: 11). Following that, Haraway proposes that we might think about technologies as forms of materialized figuration; that is, as arrangements that effect particular meaningful associations between persons and things. And given that, one question we might ask is: how are relations of humans and machines figured together? First of all, how are humans and machines, respectively, figured. Then how are they figured together, or configured, in contemporary discourses and practices of technology, and how might they be reconfigured, or figured differently and so figured together differently? And of course, reconfiguration plays as well on that term’s currency in the everyday language of systems development, where reconfiguration means rearranging the relations and connections between things. Throughout all of this my interest is always, following Barad and other feminist theorists, in the relation between cultural imaginaries – that is, the kind of collective resources we have to think about the world – and material practices. How are those joined together?

Much of my work, in the book and subsequently, has been focused specifically on machines that are created in the image of the human: humanoid machines and particularly humanoid robots.

In the paper “Subject-Objects,” which was published in the Journal of Feminist Theory (2011), I read a short video posted on YouTube 1 that’s documenting an encounter between some humans and the sociable robot MERTZ, during a one-week period when MERTZ the robot was installed in the public area of the lobby of the Stata Center at MIT—that’s the building that houses the departments of computer science and artificial intelligence. So Mertz was set up in the lobby with the idea that the robot would elicit interactions from people passing by, and this particular group of people, as many people these days do, documented their encounter with MERTZ through a smart phone video and posted it. I love this encounter because unlike most demos, which are very carefully constrained and framed and set up to show off certain aspects of the robot, this one was a much more impromptu and cinéma-vérité mode of documentation. In the paper, I play with the contrast between the researchers’ interest, which was in MERTZ’s ability to engage in functions like the accurate recognition of human faces and the mapping of the words that were said to it, and my own reading of this encounter, which looks at the entangled boundaries of subjects and objects which it seemed to me were so vividly demonstrated. I try to track the moment-to-moment, shifting choreography of this very lively object and its obliging subjects, who were doing everything they could to be successful interlocutors. I look at the ways in which, over the course of the encounter, the humans alternately shape themselves into appropriately cartoonish subjects in order to engage with the robot in the ways that it needs them to, and then reframe the robot as an object of their shared puzzlement and pleasure. MERTZ, meanwhile, is robotically translating the fragments of sound and motion that these noisy objects are emitting into readable signals and enacting its own in-built logic of more or less sensible replies. I suggest that as they are entrained by MERTZ’s vitality, the humans are robotically subjectified. When they shift their orientation to each other’s queries and laughter, the robot is correspondingly restored to human-like objectness. This interactivity of persons and things is manifest here as moments of bodily imitation and connections that are animated by affective dynamics that escape the researchers’ classification, and don’t show up in any of the graphs or in the research papers. These are, I suggest, what Donna Haraway would identify as the experiment’s “immeasurable results” (1997: xiii).

Most recently, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with Claudia Castañeda on a paper that appears in the journal Social Studies of Science, titled “Robot Visions” (2014).

The paper is inspired by this epigraph from Donna Haraway’s classic work Primate Visions. Haraway writes, “Children, AI computer programs and nonhuman primates: all here embody ‘almost minds.’ Who or what has fully human status? … What is the end, or telos, of this discourse of approximation, reproduction, and communication, in which the boundaries among and within machines, animals, and humans are exceedingly permeable? Where will this evolutionary, developmental, and historical communicative commerce take us in the techno-bio-politics of difference?” (1989: 376). In the paper, we take the project of roboticist Steve Grand, named Lucy the robot orangutan, as a kind of case to read through Haraway’s Primate Visions, to make an argument about the imaginative limits of the wider project of making robot/human lookalikes, and how it might be otherwise, how else we might be figured in our relations.

Let me return, then, to my starting image, to move us away from this more specific project of humanoid machines, back to the broader frame of the interface at which we come together with particular digital or computational devices. This is an image from a study that I engaged in, as you can see many years ago, back in the late 1990s. Andrea is a civil engineer, who was working at the time on a project with the California Department of Transportation. We were involved in a research project with them, interested in their work practices and the technologies that they used. In that context, we spent one session sitting with Andrea at her computer-aided design workstation, as she talked us through a problem that she was working on at the moment. So what she is doing, at this particular moment in the videotape from which this image is drawn, is talking to us about the intersection that she is working on designing. There was a new bridge being built across the Carquinez Strait in the San Francisco Bay Area, and the work of the civil engineers was focused on the connections between the bridge and the land on either side of the strait, which is actually where things get really complicated. That’s where the bridge comes down into communities, on top of built environments that include toxic landfills and various other things, and so Andrea was working on trying to design this exchange, this part of the highway around the complexities of that place. One of the things that we found really interesting, and that I wrote about in a paper called “Embodied Practices of Engineering Work” (2000) is that, on the one hand, Andrea’s knowledge of the object that’s rendered here was informed by many different relations that she had to this place. She had been out there, tromped around underneath the bridge where this interchange was going to be built. She had been part of many community meetings, talking about the complications of it. She had been part of many meetings within Caltrans talking about this interchange; she had read many other kinds of documents and reports about it. And all of those things were in play as she was engaging with this particular rendering of it. At the same time, this particular rendering of it made it possible for her to do things that she couldn’t do through any of those other ways of knowing. So I tried to write about the multiplicity and diversity of her knowledges, and the particular kinds of agencies that this technology afforded her.

I like looking at this image alongside this quote from Vivian Sobchack, from a very wonderful paper of hers in a book that’s titled Carnal Thoughtsmediates our figurations of bodily existences but constitutes them. That is, each offers our lived bodies radically different ways of ‘being-in-the-world.’ … Each differently and objectively alters our subjectivity while each invites our complicity in formulating space, time, and bodily investment” (2004: 136-7, original emphasis). I didn’t find this quote, of course, until many years after I wrote about Andrea, but it makes a strong connection. It also makes a strong connection to the work of Natasha Myers (2008, 2015), which some of you may know. Natasha has been looking at the forms of embodied knowing that molecular biologists incorporate – and she means this quite literally – as their understanding of protein structures, through their engagements with both physical and virtual models. She argues that interactive molecular graphics technologies afford the crystallographers whom she is studying the experience of handily manipulating otherwise intangible protein structures. At the same time, she argues that the process of learning those structures involves not simply mentation, but a reconfiguration of the scientist’s body. So, the scientist is engaging with these models and is, in turn, transformed by that engagement. She write about this: “Protein modelers can be understood to ‘dilate’”—this is a term that she takes from Merleau-Ponty—“and extend their bodies into the prosthetic technologies offered by computer graphics, and ‘interiorize’ the products of their body-work as embodied models of molecular structure” (2008: 186).

Another really compelling example of this fluidity of body boundaries is provided by the work of Rachel Prentice (2005; 2012), who has been looking at minimally invasive robotically assisted surgeries.

So this is an image, which I just pulled off the web, of the da Vinci robot. If any of you have been following this you’ll know that there have been huge controversies around this robot, which is a whole further interesting set of developments that I won’t go into. Rachel interviews the surgeons who have engaged in different kinds of surgery, from the traditional form of surgery where you literally open up the patient’s body so that you can get your hands and hand-sized instruments inside the body, to these robotically mediated surgeries, where, as you can see, you have the surgeon sitting at this console where there are also the controls, while the body of the patient is basically across the room, attended to by a whole collection of other people and the object of a lot of robotic instruments. On the one hand, it would seem that there has been this separation between the body of the surgeon and the body of the patient. There is a kind of distancing that’s an effect of these reconfigurations. But on the other hand, surgeons who are experienced in minimally invasive surgery, in doing surgery through these technological mediations, actually report that experientially they find themselves more intimately engaged with the patient’s body. So Rachel interviews an orthopedic surgeon who works on shoulders, who talks about how he imagines himself inside the shoulder of the patient, working away at it. Her work then complicates any simple ideas about distance and proximity in relation to technological mediation, and shows that we have to think about those in more complex ways.

A less therapeutic and more violent form of body/machinery configurations is evident in Natasha Schull’s (2012) really fascinating work on the interconnected circuitry of the gaming industry, the gambling industry, as it is embodied by digital gambling-machine developers. She looks at the ways in which the industry of developing these technologies comes together with machines and gamblers in Las Vegas. As in molecular modeling, the physical and digital worlds are joined together to affect the resulting agencies: in this case, this is in the form of input devices and machine feedback that minimize the motion required of players. Designers are continually trying to invent input devices that will require less and less action on the part of the user, and that can enable faster and faster rounds of betting. This includes ergonomically designed chairs that maintain the circulation of the blood and the body’s corresponding comfort, so you can sit for hours and hours and not even realize that you have been sitting, and computationally enabled operating systems that expand and more tightly manage the gaming possibilities. It includes as well software in an increasingly rapid kind of cybernetic feedback loop with the actions of the player, adjusting itself to the tempo of the play and, again, incorporating the player into closer and closer, faster and faster dynamics of betting. There is a very unfortunate collusion here in the interests of the developers, who of course want people to keep playing and to play as rapidly as possible, and players who, as they describe it to Natasha, are looking for, as she says, a “dissociated subjective state that the gamblers call the ‘zone,’ in which conventional spatial, bodily, monetary, and temporal parameters are suspended” (2005: 73). So that is the goal, and the boundary between the player and the machine dissolves into this new and very compelling union. The point, as compulsive gamblers explain to her, is not to win but to keep playing.

The theme of violence then takes us to my current work, on the emergent interfaces of remotely controlled war fighting, in which particularly my country of citizenship, the United States, has taken the lead. This is an image of one such interface, taken from an article in the New York Times in November 2010 that was titled “War Machines: Recruiting Robots for Combat” (Markoff 2010). What really struck me about this image is the caption that accompanies it. It includes this phrase, “Remotely controlled: some armed robots are operated with video-game-style consoles, helping to keep humans away from danger.” It’s the implied universality of the category “human” here—who would not want to keep humans away from danger?— along with the associated dehumanization or erasure of those who would of course be the targets of these devices, that is my provocation, my starting place in the research.

Remotely controlled killing is currently being pursued through the expansion of an institution that political theorist and US military chronicler James Der Derian (2009) has named the Military–Industrial–Media–Entertainment Network. This is an infrastructure, he argues, that enables the premise of what he calls “virtuous war.” This is what he says about that: “At the heart of virtuous war is the technical capability and ethical imperative to threaten and, if necessary, actualize violence from a distance—with no or minimal casualties” (2009: xxii). That is to our side, of course. He continues, “Fought in the same manner as they are represented, by real-time surveillance and TV ‘live-feeds,’ virtuous wars promote a vision of bloodless, humanitarian, hygienic wars. … Virtuality collapses distance between here and there, near and far, fact and fiction. It widens the distance between those who have and those who have not” (2009: xxxiv). So this idea of the asymmetry that goes along with virtuous wars, as number of commentators have pointed out, this widening of distance between those who have and have not, might help us to understand the suicide bomber as, among other things, a desperate response to these developments. In the absence of this high-tech weaponry for remotely controlled killing, what’s available is the ability to literally put your body in proximity with others, to become, yourself, a weapon. I would refer you to Derek Gregory, who is a cultural geographer at UBC and has a fantastic website titled Geographical Imaginations. In this particular post 2 , he talks about the relationship between the suicide bomber and these developments in remote control as a responsive imaging of each other.

Judith Butler has countered the premise of virtuous war perhaps more clearly and definitively than anyone, including in her book Frame of War, published in 2010. Butler challenges the historical precedent and, more fundamentally, the premise of the legal framework regarding warfare. She writes, “The international law that prohibits crimes against civilians presupposes that there can be a war without such crimes, reproduc[ing] the idea of a ‘clean war’ whose destruction has perfect aim. … But if there is no stable way to distinguish permissible collateral damage from the destruction of civilian life, then such crime is inevitable, and there is no non-criminal war” (2010: xviii). She is, I think more radically than anyone, challenging the ideas of precision that inform current war fighting in the United States.

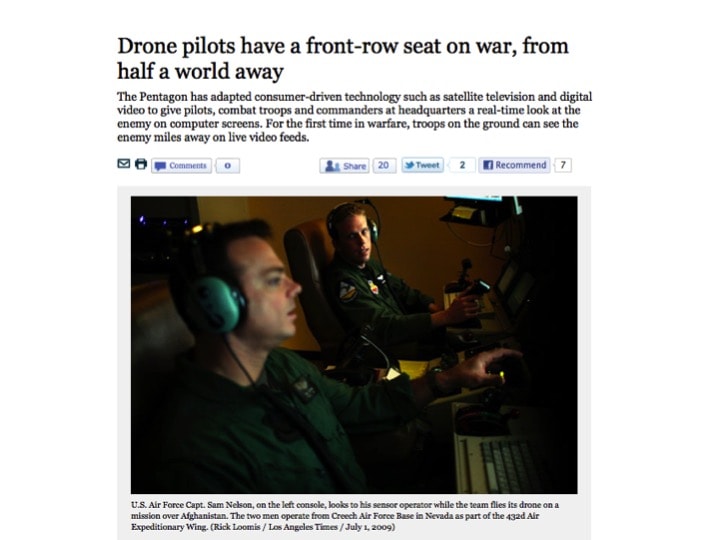

As you probably have followed in the news, there is a fascination with these configurations of remotely controlled killing in the case of drones, where we have operators who are sitting at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada and flying drones over Afghanistan and Pakistan. There are again, I think, a lot of interesting questions that I don’t have time to go into here, questions of distance and proximity in this configuration as well. Derek Gregory also writes about and has some fantastic analyses of the difference drawn between the close-up view that drone pilots report that they have, in comparison to the B-52 bomber pilot, dropping bombs with no visual awareness (Gregory 2011). Gregory points out that rather than thinking about the drone pilot’s view as an intimate one, we can think about it as the view of the voyeur or the stalker; a very particular sense of intimacy.

Obama’s war, as these operations have come to be called, is legitimated on the premise of precision in the identification of its targets. Here is a quote from Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism John Brennan, “With the unprecedented ability of remotely piloted aircraft to precisely target a military objective while minimizing collateral damage, one could argue that never before has there been a weapon that allows us to distinguish more effectively between an al-Qaeda terrorist and innocent civilians.” 3 Again, those of you who have been following the development in this area will be aware that there is an enormous amount of counterevidence for this claim of the ability to precisely identify, which underlies the claims for legitimacy of the targeted killing program. We have examples like this: Rafiq Rahman, who was a primary teacher in the so-called Federally Administered Tribal Areas in northwest Waziristan and Pakistan, recently testified with two of his children in a hearing at the US Congress regarding the drone strike a year before that killed his 67-year-old mother as she was picking okra in a field with her grandchild nearby (McVeigh 2013). This was really powerful commentary. And United Nations Special Rapporteur on Counterterrorism Ben Emmerson recently estimated, in a report to the UN Human Rights Council, that at least 400 civilians have been killed in Pakistan as a result of remotely piloted aircraft strikes since they began in 2004. A further 200 individuals were regarded as probable noncombatants (Nichols 2013). Officials indicated that, owing to under-reporting and obstacles to effective investigations—it is incredibly difficult to get into these areas—these figures were likely to be an underestimate. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism is continually doing their best to track the effects of these drone strikes (see https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/category/projects/drones/). All of this counter-evidence to the claims for precision brings into question the premise that somehow the view from the drone is one that enables a very definite identification.

So we have these claims of precision, on one hand, and mounting evidence of the profound uncertainty of identification of those who have become targets. Derek Gregory talks about what he calls the scopic regimes of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (2011). His central thesis is that the lines of site that are afforded by these regimes are inescapably tethered to the view from our side, while they systematically erase the standpoints of those who aren’t identified with the US military or its allies. He writes, “High-resolution imagery is not a uniquely technical capacity but part of a techno-cultural system that renders ‘our’ space familiar even in ‘their’ space—which remains obdurately Other” (2011: 201). I think this is tremendously important, because he is reminding us that vision is not a strictly technical matter. It’s a matter that’s deeply informed by the positionality of the gaze that is engaged in that vision, and his argument is that the positionality of that gaze makes it impossible to engage in the kinds of recognition that underlie the claims of the current programs.

To close, I’m going to just say a bit about my current research site within this larger project.

It’s represented here in an image from December 2001, but to get to the image, I’m going to fast-forward a decade or so. It’s Monday, April 2, 2012, and I’m sitting at a Peet’s Coffee Shop in Marina del Rey, California, talking to Jarrell Pair, who was the lead designer of FlatWorld, a flagship project from 2001 to 2007 for the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies, or ICT. In the book Virtuous War (2009), Der Derian identifies the ICT’s opening in 1999 as a founding moment in the emergence of the Military–Industrial–Media–Entertainment Network. Explicitly committed to strengthening the synergies of the entertainment and defense industries, the U.S. Army allocated $45 million for the first five years to the University of Southern California to create a laboratory dedicated to the development of advanced simulations. As described by Tim Lenoir and Henry Lowood in their paper “Theaters of War: The Military–Entertainment Complex”: “At the opening ceremonies of ICT, Richard Lindheim, the executive director, outlined several projects the institute would be pursuing. Among those that he described would be the construction of what he called the ‘holo-deck.’ The idea, Lindheim explained, was to leverage new media technologies of virtual reality to link immersive virtual environments with interactive synthetic agents that are elements of simulation and game-based learning exercises” (2005:35). As a first instantiation of this vision of the holo-deck, a single-room FlatWorld prototype was demonstrated in December 2001 in a warehouse space near the ICT in Marina del Rey, with physical walls and props that were created by collaborators from Paramount Studios.

Over the ensuing seven years, the project created these large digital flats—“flats” in the theatrical sense—running real-time computer graphics, augmented by physical props that act as portals into the virtual world. So you have a physical door that leads out into a virtual city square, along with sensory effects that are cued to relevant virtual objects or ambient environments. You have tactile floor speakers that simulate the flashes and vibrations of explosions. Great effort was made to incorporate what they call “mixed reality” in these projects, combining physical and digital technologies.

Back in this coffee shop down the road from the ICT in 2012, Jarrell Pair and I have spent the last hour discussing the life of the project over the seven years of its existence. And where would the archive of the project be now? I asked. “I suppose I have most of it,” he replies, and then generously offers to make it available to me. Four months later, he sends me links to 3GB of material that he has painstakingly drawn together from over a thousand files, tracing the FlatWorld project from its precursors to its last implementations. It’s this very fortuitous archive that comprises, in a sense, my current field site. And I’ve been working more specifically with a guided tour of FlatWorld as it was configured in 2005. I’m going to be showing that video in the workshop tomorrow and inviting you all to help me think about it. For now, I’ll just say a few things about it and give you a sense of my initial efforts toward an analysis.

The tour itself opens as a specifically filmic event. We see Jarrell, his hand on the door, leading into the FlatWorld simulation. He’s talking to the camera. He asks, “Filming?,” and then we hear the canonical cinematic command, “action.” But before the door even opens, we hear sounds that seem to come from somewhere other than the studio space where Jarrell and the cameraman are standing. We hear a combination of Islamic calls to prayer and gunfire in the distance, and Jarrell explains that his walk-through is not itself a story-based demo but rather is aimed at demonstrating the technical capacities of the system, with viewers invited to extrapolate its possible uses in operational settings. As becomes clear, the technical system that the demo reveals is saturated in stories, and it’s those that I’m particularly interested in.

In my first watching of the video, I was disconcerted by the ways in which Jarrell distanced himself from what I found to be its disturbing content. Helicopters and UAVs flying overhead, explosions, figures of ‘bad guys’ – the bad guy being a stereotypically keffiyeh-scarf-wrapped terrorist with an automatic weapon – whom Jarrell dispatches using his PC tablet and replaces with a ‘good guy,’ who is of course a fully kitted-out, clean-cut US infantry man, who we are to understand is responsible for saving us from the bad guy. There is a small boy who hails us—he says, “Hey, US, over here,” and then he throws rocks at us. There is a Humvee parked behind the house that provides the escape vehicle in which we imagine ourselves being taken out of harm’s way. I wonder how in demonstrating this technology, which he has been so intimately involved in designing, could he be so immune to its figurations?

The philosopher Helen Verran has suggested that rather than something to be resolved and dispelled, disconcertment can be a sign of trouble with which we need to stay (Verran 2002). In the larger project of which this engagement with FlatWorld is part, I want to focus on the military concept of situational awareness and more specifically the requirements of positive identification of an imminent threat that underwrite the canons of legal killing. I’m thinking about this trope of situational awareness through related questions of intelligibility and identification, specifically as they are taken up by Judith Butler. In Bodies that Matter (1993), Butler suggests that the intelligibility of the body includes always what she calls its constitutive outsides, those unthinkable and unlivable bodies that, in her words, do not matter in the same way. So bodies that do not matter in the same way takes on an additional resonance in the context of simulation, in the sense of bodies differently materialized. FlatWorld’s distinction between “us,” who are actual, and “them,” who are virtual plays as another layer of intelligibility and identification, which works in a very complex dynamic with other readings of us and them that are so central to the operations of war. Looking at FlatWorld, we can begin to see how our bodies, immersed in virtual environments, are transformed by them, while their virtual bodies are also reiterative and generative of actual ones. That’s the premise and the promise of simulation. These simulations are infused with a second reading of us and them, of course. Figures of us, who are Americans, are differentiated from them, who are Other. And that difference leads to a third, between friend and enemy. So what is the relation between the virtual figure of the enemy and the enemy? Situational awareness rests on a premise of recognition of that which is already there, already a threat or not one. But if we think of the enemy in the way Butler first urged us to think of sex, both need to be discussed as part of regulatory practices that produce the bodies that those same practices are designed to govern. On this analysis, like binary sex, the enemy is an ideal construct which is forcibly materialized through reiteration. And, as Butler observes, “that this reiteration is necessary is a sign that materialization is never quite complete, that bodies never quite comply with the norms by which their materialization is compelled” (1993: 2). It is those constitutive instabilities, in her framing, that afford the possibilities of transformative reparation. As with binary sex after Butler, it should be impossible to think of the enemy in any other way than performatively, as an effect of a regulatory ideal and as essentially constituent of what we can call the military imperative. For the soldier, the enemy is not simply out there, but one of the categories by which the soldier becomes viable, that which qualifies him or her within the domain of cultural intelligibility that comprises the military. So if the construction of the enemy is not a singular or determining act, but rather a process of reiteration, how might we reconcile training from training the body in recognition and response, which is the current conception of situational awareness, to training as itself productive of the entities to be recognized? Seen as another mode of reiteration, simulation is then deeply implicated in performing the realities that it cites.

So I close with a question, which sets up my research agenda. How can we think simulation and actuality together thorough their resemblances, their real corporeal connections, and articulate their crucial differences, particularly when it comes to acts of wounding and killing? What does it mean that remote control is becoming the primary operating configuration for US military operations? How do we, like Jarrell, maintain our distance from the scene of battle? What does it mean to be at once immersed in a world but not of it? And what are the leaky boundaries that undo the carefully crafted lines of connection and separation meant to keep our bodies safe and to maintain the difference between those of us who are addressed by the simulation and those figured as its objects? These are pressing questions not only for those involved in command and control of the front lines, but also for those of us responsible as citizens for grasping events in which we are, at however great a distance, politically, economically, and morally implicated.

References

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: on the discursive limits of “sex”. New York: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2010). Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? London and Brooklyn: Verso.

Castañeda, C., & Suchman, L. (2014). Robot Visions. Social Studies of Science, 44(3), 315-341.

der Derian, J. (2009). Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network, Second Edition. New York and London: Routledge.

Gregory, D. (2011). From a View to a Kill: Drones and Late Modern War. Theory, Culture & Society, 28(7-8), 188-215.

Gregory. D. (2103) theory-of-the-drone-6-sacrifice-suicide-and-drones, at http://geographicalimaginations.com/2013/08/05/theory-of-the-drone-6-sacrifice-suicide-and-drones

Haraway, D. (1989). Primate visions: gender, race, and nature in the world of modern science. New York: Routledge.

Haraway, D. (1997). Modest _Witness @Second_Millenium.FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge.

Lenoir, T., & Lowood, H. (2005). Theaters of War: The Military-Entertainment Complex. In H. Schramm, L. Schwarte, & J. Lazardig (Eds.), Collection – Laboratory – Theater (pp. 427-456). Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Markoff, J. (2010) War Machines: Recruiting Robots for Combat. The New York Times, November 27.

Myers, N. (2008). Molecular Embodiments and the Body-work of Modeling in Protein Crystallography. Social Studies of Science, 38(2), 163-199.

Myers, N. (2015). Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter. Durham: Duke University Press.

Prentice, R. (2005). The Anatomy of a Surgical Simulation: The mutual articulation of bodies in and through the machine. Social Studies of Science, 35(6), 837-866.

Prentice, R. (2012). Bodies in Formation: Remaking Anatomy and Surgery Education. Durham: Duke University Press.

Schull, N. (2005). Digital gambling: The coincidence of desire and design. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 597, 65-81.

Schull, N. (2012). Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sobchack, V. (2004). Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and moving image culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Suchman, L. (2000). Embodied Practices of Engineering Work. Mind, Culture & Activity, 7(1&2), 4-18.

Suchman, L. (2007). Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions, revised edition. New York: Cambridge.

Suchman, L. (2011). Subject Objects. Feminist Theory, 12(2), 119-145.

Verran, H. (2002). A Postcolonial Moment in Science Studies: Alternative Firing Regimes of Environmental Scientists and Aboriginal Landowners. Social Studies of Science, 32(5/6), 729-762.

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HuqL74C6KI8[↑]

- See Derek Gregory ‘Theory of the Drone 6: Sacrifice, suicide and-drones’ at geographicalimaginations.com/2013/08/05/theory-of-the-drone-6-sacrifice-suicide-and-drones/[↑]

- Speech on Counterterrorism delivered to the Council on Foreign Relations, April 3, 2012. http://www.cfr.org/counterterrorism/brennans-speech-counterterrorism-april-2012/p28100, accessed June 11, 2016.[↑]