Tiny Cameras in the New Viewfinderless Camera-Body

With neither attached viewfinder nor LCD screen, the GoPro action camera has been from its outset a consumer-grade item, a tool of the amateur who requires no orientation to his or her field of action and image conquest. As one professional photographer commented in response to an online article about the expanding market in viewfinderless cameras, “We are already predisposed to think we are shooting with an inferior tool if there is no viewfinder and we are relegated to composing on the LCD screen.” 1 His point is that the disappearance of the optical viewfinder or its displacement onto the LCD or the screen of one’s cell phone or remote computer further degrades the camera-body as a site of expert knowledge and as a tool for capturing what has been with the intentionality of the professional. 2 Competitors of the GoPro Hero line such as the Garmin VIRB Elite have introduced low-powered viewfinders, and GoPro itself made built-in viewfinders available on two models of its HERO4 cameras by 2014. 3 But this has not curbed the growth in the market for viewfinderless cameras, to which Sony has introduced the FDR-X1000V splashproof 4K, iON the Air Pro 3, and Mobius the HD Action Cam, which is two inches in size and costs under US $100. The iVue Horizon camera, mounted in polarized safety sunglasses, is exceptional among action cameras in harnessing the lens to the eye. The diminishing of the viewfinder’s centrality on these newer consumer cameras, and on the new mirrorless pocket models as well, entails an outsourcing of the cognitive and aesthetic work of the camera-body to the screen-body of the cell phone and the personal computing device, networked with the camera to allow the work of composing the shot a slightly different time and place from the location of the take. The trend toward ever smaller point-and-shoots, some with larger LED displays, suggests a turn not only toward easy, casual shooting, but also toward a kind of body-camera intra-subjective relationship that accepts the displacement of camera vision from the eye and embraces the notion of a multiplicity of lens locations around the camera-body’s field of multisensory activity.

Here we replace the notion of the field of the gaze with that of the field of sensory activity. We do this to emphasize that these cameras offer not exactly a new way of organizing the camera-body to optimize visuality, but a new way of living with cameras as multisensory tools that afford the expression of distributed experience and cognition. Through the viewfinderless form of the camera-body, experience is potentially multisensory and may not feature visuality as the most important modality of camera engagement. The experience may be more immediately physical and tactile, as in the case of the movement of the viewfinderless camera-body multiple through an immersive medium such as the ocean or the sky. In the latter medium, the camera unit might be attached to the wing of a plane in which the human subject flies, or which the subject controls from the ground; it might be suspended inside a balloon or on a kite connected to the human subject by a handheld tether. The camera-body may even cross species, as when an action camera if affixed to the back of a domesticated eagle in flight, or to lures that record the descent of a hook into a school of deep-sea cod, followed by the violent ascent of a struggling codfish to the surface of the water and onto a boat. 4 The spatial and temporal displacement of camera control releases the camera-body from the dominance of visual modalities, allowing the camera-body experience to feature other sensory experiences, such as the feel of moving through water, the auditory pressures of atmospheric changes during the period of the take, or the rhythmic movements of the bodies to which the camera is attached. The ability to use the camera as a tool of experience in these ways outweighs the importance of including and using an optical viewfinder. Indeed, if we conceive of the camera as a partial sensory tool in this way, we might propose a feminist alternative to the tacit voyeurism often coincident with the reification of the viewfinder as the professional’s tool. With each new model, viewfinderless cameras are growing smaller and more lightweight, easier to incorporate over the human body and its equipment.

As viewfinding is delinked from the camera and outsourced either to the detachable screen accessory or to an external device such as the cell phone or the iPad, the camera-body undergoes a transformation in its orientation to the photographer’s eye and seeing body, becoming detached from the eye while attaching itself over the surface of the photographer’s mobile body. In order to better understand the camera-body in relation to viewfinding, this sometimes inbuilt and flawed but more recently delinked and outsourced mechanism, we take a detour through the early period of video art and performance art, overlapping genres of practice widely recognized for featuring mechanisms geared toward the reflexive display of the self in time.

Viewfinderlessness in Video Art: A Culture of Narcissism, or a Reflexive and Distributed Gaze?

Released on the mass market in 1967, the Portapak was the first portable, handheld video recording system. Tapes, unlike film, could be reviewed immediately after recording with a portable deck, or recorded over should materials need not to be preserved. Compared to 16mm sync-sound film rigs, the Portapak was cheap, flexible, and lightweight. Leading video artist Chris Hill identified in these features of 1960s and ’70s video “a radical paradigm for a participatory democracy,” a line of discourse that others have applied to the proliferation of VHS players in the 1980s and social media technologies in the 2000s. 5 To Hill’s point, the Portapak created a means through which nonprofessionals, such as activists and artists, could develop video production practices suited to their own needs or desires. With the Portapak, camera-bodies could move from studio to street. Bringing instantaneous review to amateur price points led to the flourishing of radical video groups including Raindance Corporation, Ant Farm, Videofreex, TVTV, and People’s Video Theater, which emphasized process over product, and stories about progressive issues including gay rights, feminist political activities, antiwar movements, etc., that dominant 1960s and ’70s media organizations rarely covered in solidarity with activists on the ground. 6 Portapaks also enabled 1970s video artists such as Vito Acconci to experiment with instantaneous playback and video feedback loops, technical artifacts that centered the inward-facing, selfie-style of 1970s video art that critic Rosalind Krauss came to characterize as the “aesthetics of narcissism,” a position we revisit below. 7 Whereas film required processing and the syncing of image to sound by hand, a direct feed from Portapak video cameras to monitors allowed for subjects in front of the lens to interact live with an image. This novel quality of the video medium dovetailed with—or perhaps even colonized—Acconci’s exploration of interactivity, space, and self (or narcissism), already central to transgressive live performance works such as Seedbed (1971), Security Zone (1971), and Transference Zone (1972). Certainly the risk-taking central to 1970s video and performance art finds echoes in the viewfinderless use of wearable digital cameras circa 2010, a point to which we return below. In light of our previous examples, we note for now simply that a video recording expresses the passing rather than the stopping of time, as in the Brownie and sonogram, and so affords a different kind of viewfinderless camera-body system, one that we see as a significant antecedent to current uses of wearable cameras like the GoPro. The often live, temporal event rather than the still became the medium of the viewfinderless, selfie snapshot in video art. Such video technology was ready-made for uptake—even internalization—by performance artists.

In her seminal essay “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” Krauss criticized the turn to live video art as lacking avenues for expressive growth and development. In Freud’s terms, narcissism in adults refers to the overvaluation of a subject’s investment in the self as an erotic object, to the detriment of his or her capacity to empathize with others. Aiming to achieve their ego ideal (the reenactment of the subject’s childhood unity, for Freud), the narcissist enters a vicious cycle of overestimation of his or her abilities, followed by the frustrating failure to live up to them, which triggers the defense mechanism of turning further inward. 8 Of interest in this critique of the narcissism of the live video image in the immediate and proximal form of self-documentation projected live is the externalization of the viewfinder onto the public gallery screen. The recursive live feedback loop essentially collapses the difference constituted through technical conditions of the lens relative to the viewfinder such as parallax, the displacement of the camera lens in relation to the embodied eye of the camera operator in SLR and TLR cameras, and viewfinderlessness. Citing as exemplary of this trend Acconci’s parodic take on 1960s formalist art theory, Centers (1971), Krauss argued that exploring the live broadcast video apparatus in fact centered a narcissistic feedback loop rather than reflexive art, undercutting the possibility for critical thought and growth. At the beginning of the 20-minute video, Acconci, framed in close up, raises his right arm and points at the center of the TV monitor live broadcasting his own image just above the lens of the video camera, a pose he holds for the duration of the work. While Acconci’s joke was clearly an attack on 1960s formalist notions of proper framing, Krauss has read it elsewhere as endemic of a nascent cultural shift from reflexiveness in modernist art to “mirror reflection” actualized in Acconci’s use of the live video monitor. “At its present and future levels of technology,” Krauss speculated about the subject of video, “the ease of defining it in terms of its machinery does not seem to coincide with accuracy.” 9 Rather, “video’s real medium is a psychological situation, the very terms of which are to withdraw attention from an external object-as-Other and invest it in the Self.” 10 At the center of this argument is the matter of liveness. Videotape and film media differ from live video transmission in that the separation between the moment of recording and the public display of the finished work constitutes the distance required for reflexivity. Following from this logic, personal video technologies such as the digital camcorder and the webcam further shrink this critical gap and raise the prospect of narcissism on an even more massive scale than did the closed-circuit video loop of the 1970s.

The question of the use of narcissism in art as a political strategy, however, remains unresolved. Amelia Jones has argued, against the attacks of feminist art critics such as Krauss, that performance art and video art perform their critique by visibly working through narcissism and psychic fragmentation, here figured as an affirmative expression of being by bodies historically marginalized from representation in the art world. Fractured subjectivity had always been the lot of “abject beings who otherwise form the outside to the domain of the subject,” she has argued, and so she celebrates the possibilities of live performance art and video art to challenge normative ideas about gender, race, family, sexuality, the boundaries of proper art, etc.—not as a way to recover a lost whole, but as a means to displace the idea of wholeness with fleshy, breathing, vulnerable, contingent beings offering themselves to co-present audiences for myriad interpretations. 11 We would add here that the photographic images taken by observers of live performances help to facilitate access to these performance works today, suggesting that the performing bodies that attracted the cameras of others might be seen as a key part of a distributed, viewfinderless camera-body system. We probe the matter of liveness and performativity in viewfinderless camera bodies in two cases below that we see transitioning from the still to the moving image.

The Performativity of the Viewfinderless Camera-Body

Philip Auslander has long been a critic of the idea, proposed in the writings of Peggy Phelan and Herbert Blau, that “liveness” in performance is constituted in the encounter between the bodies of performer and audience. 12 In a 2006 discussion of this concept of liveness, Auslander posits a hypothetical question about the role of documentary recording technology in performance art. He distinguishes between two kinds of performance documentation. In “documentary” documentation, the camera records the performance amid spectators and serves to simulate the spectators’ view of the performance itself for future viewers, i.e., those not present at the live event. Auslander asserts that performance artists understand that their careers are tied to the distribution of documentary records through the media, and so increasingly have choreographed their work in anticipation of a camera as much as for a live audience. In “theatrical” documentation, the performer might perform only for the camera but anticipate an audience seeing this record in the future.

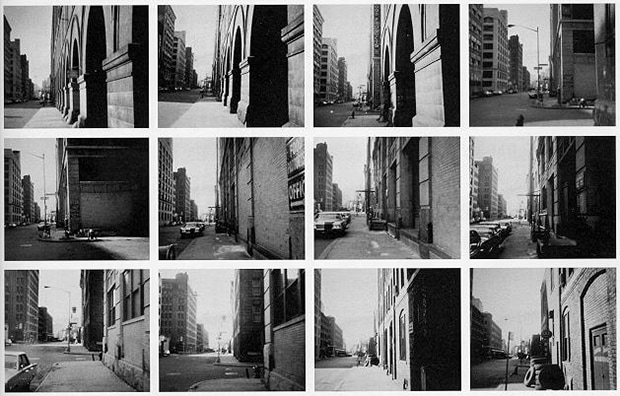

Auslander interprets Vito Acconci’s performative series of photographs titled Blinks (1969) as a work that complicates this binary between documentary and theatrical modes of performance documentation. 13 Twelve square photographs, arranged in a three-by-four rectangle, depict views down a sidewalk of a New York City street, contextualized on the gallery wall by a placard stating the rules Acconci followed to make the work: “Holding a camera, aimed away from me and ready to shoot, while walking a continuous line down a city street. Try not to blink. Each time I blink: snap a photo.”

For Auslander, the work raises questions about the temporality and location of the performance of the photographer, which is distributed across the time of his recording in the street and the time of spectatorial contemplation in the gallery. Someone might have seen Acconci taking his photographs live without knowing that s/he was witness to a performance. At the same time, the viewer in the gallery sees only these prints, not the live activity that was required to create them and considered to be integral to the work. They are fragmentary records of an experience, albeit an experience that is unspectacular and even mechanistically simple in its scope and execution. Nonetheless, the spareness of the photographs and explicitness of the rules behind Acconci’s live act emphasize that his activity in relationship to the camera’s take, and his activity as a camera-body, are the objects of the work. In this series, the photographs testify not so much to that which has been before the lens, but rather to the once-live performance of photographic recording conjoined to subsequent acts of viewing that constitutes this particular camera-body. Because Acconci snapped photographs only when his eyes were closed, the work is essentially performed in a viewfinderless mode. It is the instances he did not see that viewers of the work in the gallery see. We do not see what he saw; rather, we see what his body was present to at the time of the take. The time of the take and the time of the walk are fragmented into two sets of intermittently composed moments, one discontinuous set that we see and one that is inferred as having been experienced between those unseen but felt moments. Displayed in series, the photographs collapse the evidence of multiple instances of past time into a composite of fragments in the present time of their exhibition. Twelve moments hang on the wall at the same time. This composition of temporalities is organized around the counterpoint of the lens and the eye of the photographer as two sets of space and time relationships. The connection between image and knowledge is severed when seeing is displaced onto the lens of the camera: the camera documents precisely those moments that the cognizant experience of the body has failed to see at exactly these moments of camera documentation. This counterplay of seeing camera and experiential subjective camera process sans vision suggest the condition of viewfinderlessness that we have been addressing through historical precedents in camera design, photography, and in the engineering of sonography as a cameraless medical imaging form. This emphasis on the lack of congruence between seeing and the take resonates with the British philosopher of language J. L. Austin’s distinction between performative and declarative utterances, compelling the thought “someone did this” rather than “that happened” or “did that happen?” We wish to draw attention to this work as a performance of the distributed camera-body. The work, which includes the performance and the displayed photographs, is a composite through which seeing is multiple and displaced in the form of relays of time and space. The status of the camera-body is emphasized as not having the capacity to find its own view without the photographs that situate it through their display elsewhere and later. This is to be understood as an intersubjective process situated between the activity of Acconci and the camera, and between Acconci’s activity and the activity of the viewer who later perceives evidence thereof, seeing in a series of static frames what the artist did not see. In addition, one does not see all that Acconci did witness, but which the camera did not record, during the periods between the take of each of the twelve frames.

Auslander commends Acconci for his process in Blinks within the context of performance theory. He sees in Acconci’s piece myriad possibilities for the genre and a host of challenges to canonical theory about the anticapitalist ontology of the body in live performance. From the viewpoint of camera practice, Auslander’s theory about the documentary in the realm of performance offers a useful framework as well. He is writing for theorists in the domain of performance studies who claim there is something worth noting about the specter of mortality evoked in the encounter between bodies, and that photographed live performance can play a role in shaping the sensations that such an encounter might produce in its iteration of past experience. The performer with the camera embarks on an unstated performance without a live audience. The presentation of the styled documentary record at a later date, in a different context, reanimates the record. As the viewer sees the image, the imaginary of the performance comes alive.

As we will show shortly, this formulation aptly describes the contemporary use of the small viewfinderless action camera as a tool for recording activity. Acconci could have undertaken his performance anytime, and anywhere, which was part of the point. There was nothing spectacular or sensational or risky about the performance. Because of this, it loses its connection to contingency, to the spirit of liveness described by Herbert Blau in a rejoinder to Aulander’s reading. 14

Acconci, in his own conceptual framing of his works of the late 1960s, makes reference to two concepts in social-science research of the period: Kurt Lewin’s field theory and Erving Goffman’s interaction rituals theory. 15 Kurt Lewin’s famous dictum, posited in his classic Principles of Topological Psychology, is that analysis starts with the situation as a whole. This idea can be compared to Barad’s concept of intra-action, which also provides an expanded notion of what constitutes a single phenomenon. 16 Interaction, for Lewin, is the relation of the concrete individual to the concrete situation, understood to occur in space and over time. As Günter Berghaus notes, Acconci’s use of Goffman’s interaction studies in Blink and other works of the period (such as Proximity Piece and Following Piece) offer a method for using the camera as a recursive tool in the documentation of ritualized interactions. The camera facilitated—or even provoked—experimental staging and the study of interaction between individuals and among individuals, technologies, and spaces. 17 In these projects of the 1960s as well as in video art of the 1970s, the camera served as a means of documenting the difference between the lens and the videographer’s eye. These performances also created circumstances in which the camera attaches to the body of the videographer in multiple sites. That is, the camera is proximally intimate with the body without offering the videographer the cohesion of an uninterrupted, live continuous view through the lens. The camera becomes as if viewfinderless. When Acconci turned the (video) camera to the task of self-monitoring in works such as the 1973 performance Recording Studio from Air Time, 18 he used the trope of the mirror present in the examples of the box-camera selfie discussed earlier to film a monologue putatively spoken to and about a woman, a romantic partner with whom he lived. “I’m talking to you so that I can see yourself the way you see me,” he rambles. The performance has been widely analyzed for its display of male narcissism; however, we might also note the use of voice as a “mirrorless” imaging mechanism—as a means of underscoring the absence of proximity and intimacy. Regarded as a performance that places the personal in a public sphere, it is also an enactment of intrasubjective fantasies of intimacy with another that never occur. That the imagined recipient of the narcissist’s address is constituted through absence and disjuncture is the point of the work.

We are suggesting that the video apparatus of the self-documenting gallery performance artist and the camera-body of that world may do more than constitute the grounds for a culture of narcissism. This relationship may also offer the conditions of intra-active disjuncture and dislocation that we have been associating with the viewfinderless camera and its historical precedents, among which closed-circuit video may be counted.

In the performance and gallery work titled Adjunct Dislocations (1973), the Viennese performance and media artist VALIE EXPORT mounted cameras to her body front and back and walked from a suburb to Vienna while a third camera documented the passage of her body. 19 Writing from the performance studies field, Mechtild Widrich describes the project as approaching cinéma-vérité, a 1970s genre of film practice that entailed documenting the unfolding of experience before the continuously running camera. 20 But here we wish to emphasize the elements of temporal and spatial dislocation highlighted in the titles of this series and to draw attention to the placement of the cameras, which are positioned to make a document of where the artist has been and where she goes—not from her eyeline precisely, but from the physical standpoint of her torso as a kind of organic “dolly” transporting two cameras. The circumstance of the artist relative to the finding of a view is always, as the title of the work indicates, dislocating and adjunctive in a dependent and facilitating position that does not entail her seeing what is being filmed. This is quite different from the figure of the cinéma-vérité camera operator, whose charge is to document precisely what he or she is witness to.

Perhaps the most apt of VALIE EXPORT’s works to consider in light of viewfinderlessness is Action Pants: Genital Panic, a work of performance. 21 A set of six identical posters dated 1969, from photographs by Peter Hassman, shows EXPORT wearing a leather shirt and a pair of pants from which a triangular hole has been cut from the crotch to frame her genitals. Legend has it that EXPORT wore these pants in a Munich theater, parading the aisles with her crotch at face level with seated audience members. We might regard the pants, with their framing cut, as a kind of viewfinder. EXPORT’s putative public exposure is disruptive, provoking attention to the act of sexualized looking and forcing a reaction of reflexivity, making the reaction of looking strange, and unsettling the banal routine and tacit acceptance of glancing and staring, or being the object of glances and stares.

We might consider EXPORT’s “action pants” in light of situated action analysis, specifically considering the suggested public performance, and the suggestible posters, as examples of what ethnomethodologist Harold Garfinkel has called “breaching experiments.” 22

Breaching experiments involve deliberate breaks with socially acceptable norms of behavior in public. The public’s reaction to the staged breach becomes the focus of observation and study. In breaching studies, it is the researcher, or his or her surrogate performer, who sets out to stage the violation of a social rule, and then observes and studies the outcome of that disruption. Although EXPORT’s supposed foray into the cinema in her “viewfinder pants” is regarded as having produced a reaction (as a catalyst), we want to suggest, in keeping with the tenet of breaching experiments, that in fact she was simply making obvious what was already a tacit practice, i.e., an interaction performed routinely, unmarked, in everyday public space. What is framed is not so much the crotch per se, but the routine act of the look at the (otherwise covered) crotch that is typically taken for granted. For Garfinkel, the staged breach is not so much an experiment as a “demonstration meant to produce disorganized interaction in order to highlight how the structures of everyday activities are ordinarily created and maintained.” 23

We suggest that EXPORT’s posters stage the breaching performance not in the public space of the theater, but in the minds of the posters’ spectators in the public space of the gallery. The posters invoke mental reconstructions of a scenario in which EXPORT supposedly performed this scene in 1969. The breach experiment is in effect in the gallery space, where public fantasies about past activity, thrills, and disruptions of the norm take place on the basis of documents widely regarded as being possibly fictitious, produced to generate precisely such a breach in the relationship between documentation and fantasy around daring transgressive acts. The element of fiction and hyperbole in the documentation of risk is brought into the spotlight.

- Sanford Edelstein, comment posted to Photo.net in a forum on mirrorless digital cameras, March 9, 2012.[↑]

- The concept of intentionality has been at the center of debates about ANT and post-ANT theories of human and nonhuman agency, but there isn’t space here to bring this line of inquiry to bear on our analysis of intentionality in photographic composition.[↑]

- Two of the GoPro HERO4 editions come with a screen embedded into the back of the camera, perhaps signaling emerging distinctions between professional and amateur in the action-camera genre. The entry level GoPro, suggestively, still does not come with an LCD screen.[↑]

- See Bob Kelland, “Codfish Biting Camera,” video posted at Youtube.com, July 26, 2012.[↑]

- Quoted in Stephanie Tripp, “From TVTV to YouTube: A Genealogy of Participatory Practices in Video,” Journal of Film and Video 64, no. 1 (2012): 5–16, at 5.[↑]

- Ibid, 6.[↑]

- Krauss, “Video.”[↑]

- Sigmund Freud, “On Narcissism: An Introduction,” in The Freud Reader, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Norton, 1914), 545.[↑]

- Krauss, “Video,” 52.[↑]

- Ibid, 50.[↑]

- Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing the Subject. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 50.[↑]

- Philip Auslander, “The Performativity of Performance Art Documentation,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 84 (2006): 110. See also Auslander, Liveness; Peggy Phelan, “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction,” in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993), 147–168; and Herbert Blau, “The Human Nature of the Bot: A Response to Philip Auslander,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 70 (2003): 20–24.[↑]

- Vito Acconci, Blinks, November 23, 1969, available at Aleph-Arts.org.[↑]

- Blau, “Human Nature.”[↑]

- Acconci, Following Piece (gelatin silver print, 1969), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[↑]

- Kurt Lewin, Principles of Topological Psychology, trans. Fritz Heider and Grace M. Heider (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1936), 17.[↑]

- Günter Berghaus, Avant-Garde Performance: Live Events and Electronic Technologies (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 1891. Goffman’s interaction studies method can be found in Erving Goffman, Interaction Ritual: Essays in Face to Face Behavior (1967; Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2005).[↑]

- http://www.stedelijk.nl/en/artwork/10111-recording-studio-from-air-time[↑]

- VALIE EXPORT, “Clips from Adjungierte Dislokationen(1973),” Youtube.com, November 10, 2007.[↑]

- Mechtild Widrich, “Location and Dislocation: The Media Performances of Valie Export,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 99 (2011): 53–59. [↑]

- VALIE EXPORT, Action Pants: Genital Panic (six screenprints on paper, 1969), Tate Gallery.[↑]

- See Harold Garfinkel, Behavior in Public Places (New York: Free Press, 1963) and Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order (New York: Basic Books, 1971).[↑]

- Garfinkel, Studies in Ethnomethodology (New York: Polity Press, 1991), 36.[↑]