Some Precedents to “Selfie” Technique: Metal-Plate Photography and the Somascope

The history of technical innovation in the development of cameras and imaging systems offers useful accounts of self-documentation as a means of testing and demonstrating an apparatus in research and development phases. The examples we review below are offered as evidence that there is a rich history to be written of the media apparatus that is the viewfinderless action camera, and that this history may include instances of imaging systems that do not fall within the range of consumer-grade cameras and imaging devices. We have selected examples of camera and imaging systems in which point of view comes into play and which were regarded as being technologically flawed or failed experiments. The “flawed” documents of self we chronicle may in fact provide a history in the margins leading up to the peculiar modalities and subjective positionings of the viewfinderless action camera-body. In this section we offer two examples from numerous possibilities in the history of recording-technology research and development, expanding our sites from photography to include other scientific recording devices.

In October 2013, Digital Information World published an infographic about the selfie phenomenon. The article’s remarkably short timeline gave “selfie” an eight-year history, crediting Flickr with the earliest usage of the term. “We now live in a time,” the infographic proposed, “during which sharing your own photo online is not only common but also an accepted pillar of our digital identities.” 1 The technological history of self-documentation gets brief mention. Among the five items listed on the eight-year timeline is the release of the iPhone 4 with front-facing camera, which is described as affording the user “complete control over framing,” and the addition of ultra-wide-angle lenses in mobile phone models such as the Droid DNA, which made possible the inclusion of more context in the frame.

The Huffington Post was among a number of media outlets that gave a brief historical account when selfie was designated the “2013 word of the year” by Oxford Dictionaries. 2 Along with The Huffington Post, Public Domain Review placed the selfie in the context of the history of photography, noting that the photographer was in some cases reflexively the subject in images documenting watersheds in photographic research and development:

Although the rampant proliferation of the technique is quite recent, the “selfie” itself is far from being a strictly modern phenomenon. Indeed, the photographic self-portrait is surprisingly common in the very early days of photography exploration and invention, when it was often more convenient for the experimenting photographer to act as model as well. In fact, the picture considered by many to be the first photographic portrait ever taken was a “selfie.” 3

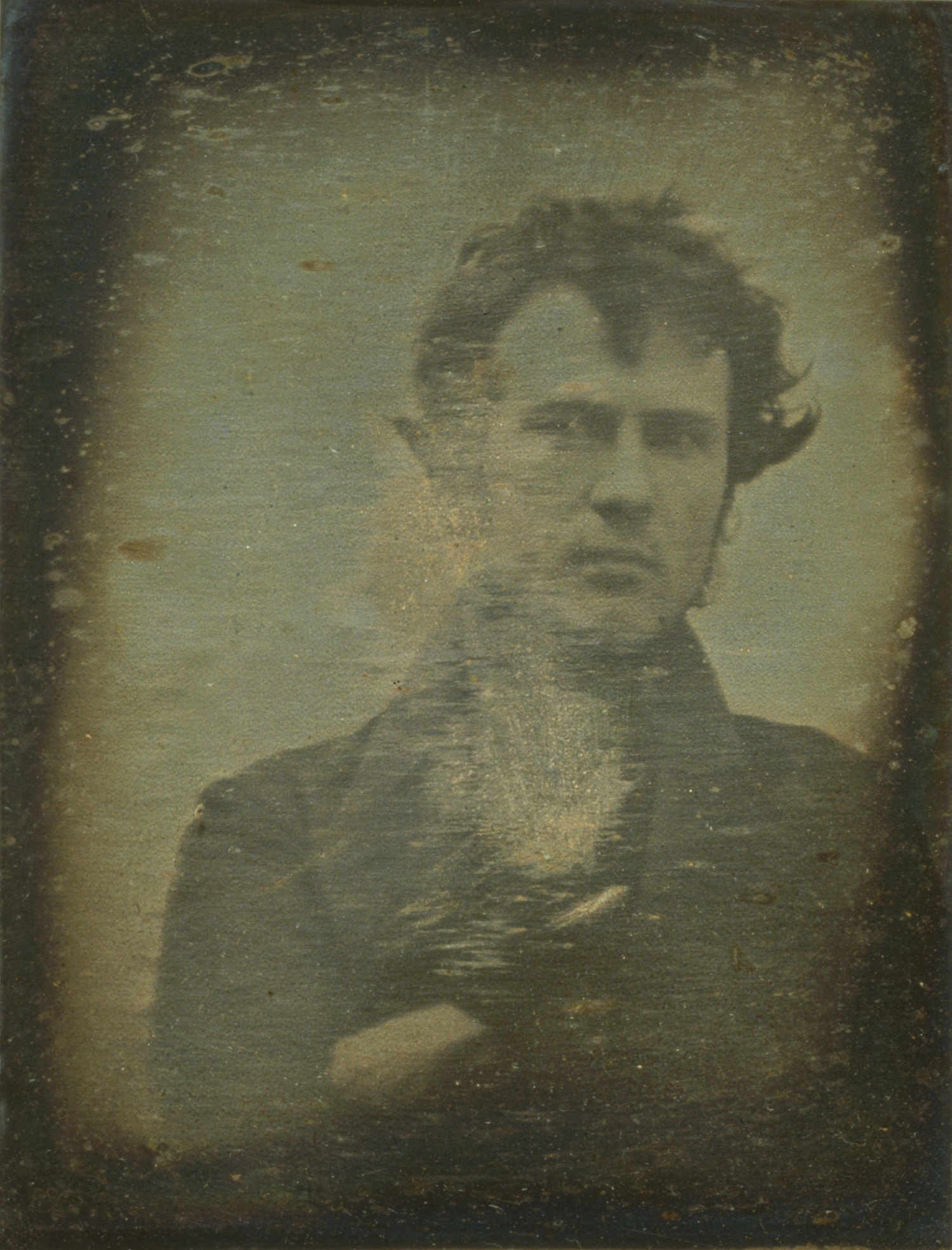

The image presented for discussion by the Public Domain Review is a quarter-plate daguerreotype made in 1839 and held in the Library of Congress’s “American Memory” collection. On the back of this daguerreotype is written “The first light Picture ever taken. 1839.” The daguerreotype depicts its maker, Robert Cornelius, a chemist and metallurgist who worked in his family’s gas and lighting business in Philadelphia. Sean Ross Meehan, in his account of photography in American autobiography, notes that not only is this daguerreotype a designated “first” in American photographic portraiture a self-portrait; it also contains significant representational failures. The image is blurred and the figure, Cornelius himself, is framed off-center. 4 Cornelius accounted for these flaws in describing the conditions of the take, which, he explained, involved at least two instances of temporal and spatial disaggregation: between the photographer’s act of seeing and the take through the lens; and between the take and the viewing of the recorded image. “You will notice,” Cornelius explains, with reference to the 1839 self-daguerreotype,

the figure is not in the center of the plate. The reason for it is I was alone, and ran in front of the camera after preparing it for the picture, and I could not know until the picture was taken that I was not in the centre. It required some minutes with iodine to produce the effect. 5

Early efforts to make portraits required sittings in bright light, keeping one’s eyes shut tight, to expose the photographic plate for as long as an hour. Photography could blind its subjects, a feature of the process that might be compared to the propensity for risk-taking in the sports and adventure genre of viewfinderless video. Cornelius may have been an amateur photographer, but he was a renowned specialist in silver plating and metal polishing (one of his commissions was from the newly established Smithsonian). When it became known that silver plates could be useful in photography because their exposure to bromine vapors would shorten exposure times considerably, Cornelius would be tapped for his skill with metals. The “selfie” discussed here is rare early evidence not only of the photographic (self-)portrait, but also of the use of metal plates. After operating a photographic studio for a few years in the early 1840s, Cornelius left the business and returned to lamp manufacturing and gas and lighting, illuminating Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial.

We recount this history of the technology with this resurrected “hero” of the early era of photography to foreground two points: first, the “selfie” in its early photography era iteration was produced through experimentation involving the body of the researcher himself. This portrait reflexively documents the activity of experimental research as an engagement with process in its critical time-sensitive dimensions (and in its physical risk potential as well). As we will elaborate below, these factors of documenting process, of bodily risk, and of technical action prowess come back into play in recent viewfinderless action-camera video that documents breakthroughs in domains such as sports, nature exploration, and engineering. Second, documentation occurs through what Meehan and others have described as “failures” and “defects.” And yet the “failures” evident in the photographic image are in fact evidence of later imaging processes and equipment potential in experiments that spin off from the irrepressibly interesting qualities of these artifacts. For example, the uncentered blur of Cornelius’s image may be interpreted to prefigure the aesthetic of blur in the multiple-camera viewfinderless action-camera image. Uncentered composition and blur have become standard compositional features and highly valued aesthetic qualities of the images produced with these cameras, offering records of conditions such as speed and mobility—qualities that subsequent to Cornelius in the nineteenth century would be features of cinematography, but which at this moment were artifacts, distracting traces of process, disruptions to the aesthetic codes of early still photography. By finding such precedents to the viewfinderless action camera-body in the history of chemistry and metallurgy, we are able to trace a history of this apparatus in the margins of a more conventional photographic history, allowing us to understand the wider history of interrelated technologies into which the camera body falls.

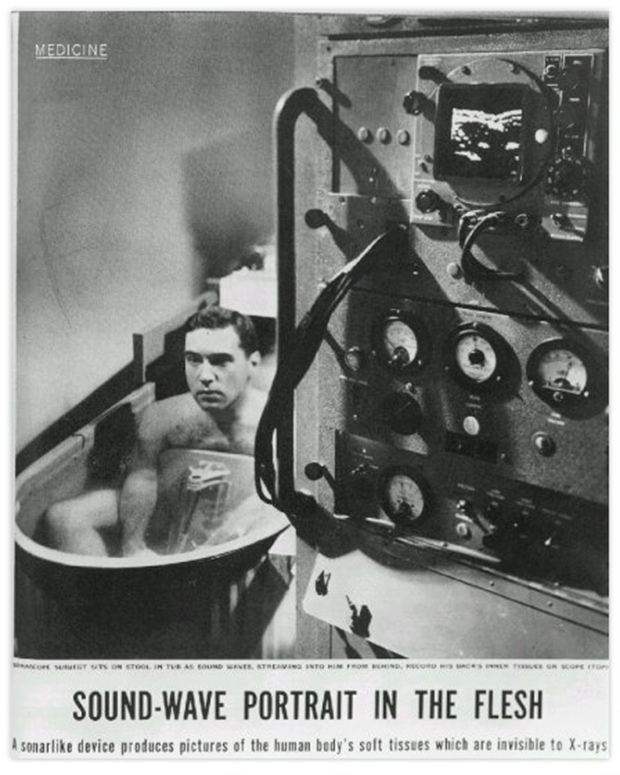

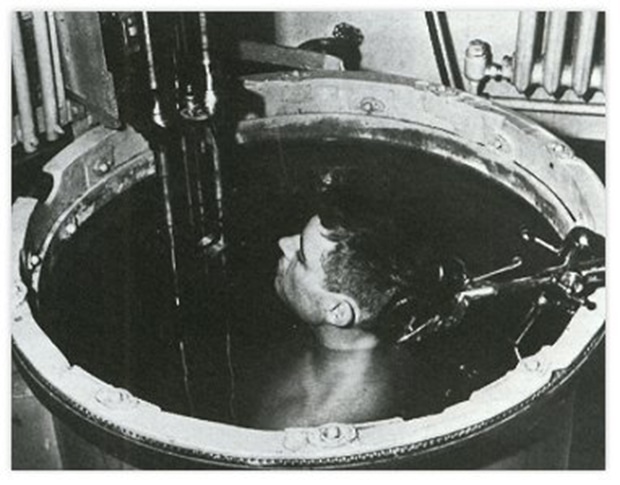

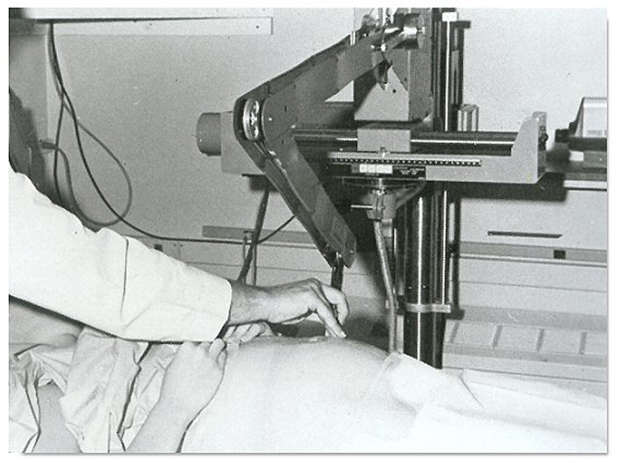

Our second example of a case of experimentation with a recording device comes not from the history of photography exactly, but from the intersecting histories of military and medical engineering of recording devices. We note the development of an instrument called the Somascope, an early ultrasound scanner developed in the mid-twentieth century by radiologist Douglas Howry with electrical engineer Roderick Bliss, radar specialist Carl Spauling, and engineers Gerald Posakony and C. R. Cushman. The Somascope, an assemblage constructed through the postwar logic of military surplus bricolage, was essentially an open water-bath scanner built in its various iterations from a repurposed horse trough and a cast-off B-29 gun turret. Some of the earliest 2D cross-sectional ultrasound images of internal structures were produced using this apparatus between 1948 and 1954. 6

The design of the Somascope employed the theatrical logic of viewing in the round. A human subject (in the testing phase, one of the researchers) sat immersed in water inside the tub. In a reversal of the logic of the 360-degree pan, the researchers mounted a transducer to a track rigged along the circumference of the tub. As the transducer circled the human body immersed inside the tank, it pulsed sound waves through the body from every angle, much as radiation is passed from different points around the circumference through a body inside a CT scanner. The transducer, a device that served as both transmitter and receiver, was submerged in water along with its subject, where it could pass around the full perimeter and image the subject in the round, rather than, say, shifting back and forth on either side of the body to render it in two flat planes. Images produced by the team included a scan of the forearm of one of the researchers, an image that we propose constitutes a kind of technical selfie, if understood along the lines of the Cornelius image discussed earlier.

As in the Cornelius process, in the Somascope process the take is experimental, and the researcher/photographer is not able to see or accurately predict what the record will show until sometime after the recording is complete. Like the Cornelius daguerreotype, anatomical recordings made with the Somascope were regarded as crude and blurred, requiring labels cross-referencing with an anatomical diagram in order to be deciphered. 7 We suggest that it may be productive to consider the Somascope, and other ultrasonography recording apparatuses developed during this period, as part of a group of implements, along with cameras, that make up technologies of documentation of the body and the self. The fact that “flawed” researcher self-documentation figures in the history of the two technologies discussed thus far interests us greatly, especially because orienting devices such as viewfinders are absent in both these cases. We are also interested in the Somascope researchers’ establishment of a 360-degree internal space as the imaging field, and their interest in documenting the body in its full dimensionality and not through frontal or planar images (though the images in this format, as in CT scans, are in fact rendered as planar composites). The registrations of the transponder as it moved around the body produced what we might call an intra-subjective, rather than an intersubjective, gaze as the device’s orientation. These concepts resonate with the later mobile camera, dimensional and distributed orientations of viewfinderless action camera practice. If it can be said that Cornelius and the Somascope researchers produced early “failed” attempts at anatomical rendering, we might look to these cases as possible precedents in the emergence of an aesthetic of viewfinderless photography featuring qualities such as uncentered composition, displacement, partialness, fragmentation, and blur.

These two instances of incidental technical “selfies” are perhaps incommensurable, with one drawn from the history of photography and the other from medical imaging. Yet we recall once again that Cornelius was first and foremost a metallurgist and chemist. He only briefly experimented with the medium of photography—and then in its metal-plate phase. By placing these instances of researcher self-documentation together, we might begin to see the possibility for a history of viewfinderlessness, ocular reduplication and displacement, and multiple sources of mobile framing constituting a self for whom visibility and self-perception are always partial, deferred, and weak in the process of documentation. The photographic camera becomes one of many tools of intersubjective and intra-subjective looking in which the embodied eye is displaced if not entirely subordinated in the process of rendering a view.

Displacing the Eye, Losing the Viewfinder

It may be argued that the camera-in-the-round approach of the Somascope or the CT scanner and the POV camera style, in which the mobile gaze emanates from the eyeline of an implied human subject, are in fact different modalities. But we wish to suggest that they are connected in important ways, particularly in that both kinds of processes point to an embodied human subject at the center of the implied lenticular logic. In the case of the Somascope, the “camera” (the transponder) is disembodied, detached from the photographer’s body. It follows a track around the subject remotely. But in our example it is the researcher himself inside the tank that is both the subject and the object of this remote tracking camera-gaze. The oscillation of proximity and distance between the intra-camera “eye” (the implied lens of the transducer) and the eye of the human subject who seeks the experience of immersive looking is not so different from the situation of the 360-degree pan that establishes the human subject at the center point of the field of the gaze, except that in the latter case the eye is mirrored at the locus of the field. The pan is as immersive an experience as that of the subject who is situated inside and outside, in the time and space of the Somascopic bath and outside that field, computing the data that traces his internal spatial densities. By interpreting this kind of process as intra-action, we may regard the partial components of the process—the different researchers, their regard of one another, as a unit—as a phenomenon, using Barad’s sense of that term. The factor of identification is critical here: the experience of the figure in the bath and the ontological condition of his relationship to the equipment of the Somascope and the team’s interpretation of its data must be translatable to other bodies immersed at other times. It is a system of seeing that is at stake here, one that is not just about the gaze of the scientist but about the reciprocity and disjunction of “ocular” locations.

We now wish to connect this logic to that of the everyday camera, tracing patterns of immersion, intra-action, and partial displacement in everyday consumer-grade imaging equipment. For this step we return to the Brownie. Greg Siegel, in his book Forensic Media, describes the characterization of the Eastman Kodak Brownie cameras as “little black boxes” in popular literature and in Kodak promotional materials during the early twentieth century. 8 In a passage quoted by Siegel from the popular magazine The Mentor, the Brownie is put forward, in 1928, as a black-boxed tool of knowledge through which one learns “what this earth is like”:

Like the magic carpet of the Arabian Nights tales, it whisks you anywhere and everywhere. This is black-box magic but worked with no abracadabra, no aid of a djinnie [sic] conjured forth from a bottle, lamp or ring. Just the modern magic of a little dark box, a roll of light-sensitive film, a disk of glass and a clicking shutter. But because of it any small schoolboy knows more today about what this earth is like than the wisest of the Greek philosophers. 9

The subject of the Brownie camera figures here is a boy—a little boy. The knowledge he gains might be described as of a metaphysical order, surpassing even that of Greek philosophers. But importantly, through his camera he learns not about the world, but “what this earth is like.” The emphasis is on situated experience. His experience is described in terms that are both phenomenological and ontological. It is the experience of being whisked not only above the earth; the figure conjured here does not engage in remote aerial optics, but physically flies around the earth’s circumference. Here we find once again the experience of an embodied mobile gaze and seeing experienced physically in the round, through circling the object of one’s gaze and directing a recording device at it, while passing through an immersive medium (in this case, the imagined atmosphere of earth through which the magic carpet flies). The carpet is a kind of mobile transponder, a tracking device from which the body is not remote but attached.

Of course, the Brownie offered no such access to world viewing. But it did entail a kind of separation of eyeline from object, and it is this point that we will seize upon to make a simple argument about the camera body of the early Brownie and its composite camera-body apparatus in the construction of early consumer-market camera self-portraits.

In this glass-negative self-portrait produced in 1900 by a consumer of the early box camera, the subject looks into a mirror to orient herself for the take. The mirror appears to be temporarily placed, resting precariously on a chair. It is propped next to an ornate shelf, which supports a collection of photographs—myriad framed portraits displayed at face level, a few figures in landscapes on the lower shelves. The landscapes sit below the standing subject’s line of sight, as does the camera. Holding it well below the level of her eye, the photographer shoots her reflection from the hip. This displacement of the camera from the position of the eye is not surprising since the Brownie, the first model of which was introduced in the year this photograph was taken (1900), initially lacked a complex viewfinder. In the place where a viewfinder might be mounted, the letter V was embossed in the camera box, indicating the direction in which the interior lens points. The V aligns and orients the photographer, serving in essence as a kind of lens-less viewfinder. The number 2 Brownie, introduced in the following year, did in fact include a viewfinder, and an accessory viewfinder would be made available in later years. We wish simply to point out here that the absence of the viewfinder in the early model and other box cameras of the period suggests that the condition of viewfinderlessness, present from the camera obscura forward, is not an exceptional state of camera being. As noted earlier, a case can be made on the basis of the early pinhole camera or camera obscura that the viewfinder is not an essential component of the camera, but here we wish to note that viewfinding is as simple as the directional, indexical act. The V, standing in for the absent lens, points. Can it be that physical orientation to an object or in a field may in fact be more fundamental than seeing to the performance of photography? Conditions worthy of consideration, in rethinking viewfinderlessness as a condition of camera history, include the displacement of lens orientation (the camera’s implied eyeline or “look” shifting from the position and angle of the embodied eye to emanate from other parts of the body) and the use of mirrors to reorient and bend lines of vision in SLR cameras. The latter occurs not only inside the camera box but also in the subject’s visible field of the gaze, as we see in this 1900 use of a mirror to stage a Brownie self-portrait. The photographer has effectively made the room into a virtual black box—an intra-active field of the gaze in which the phenomenon of self-identification is on the one hand partial and disjunctive, and on the other hand unitary and all-encompassing of a world, much like the Somascope’s interactive range.

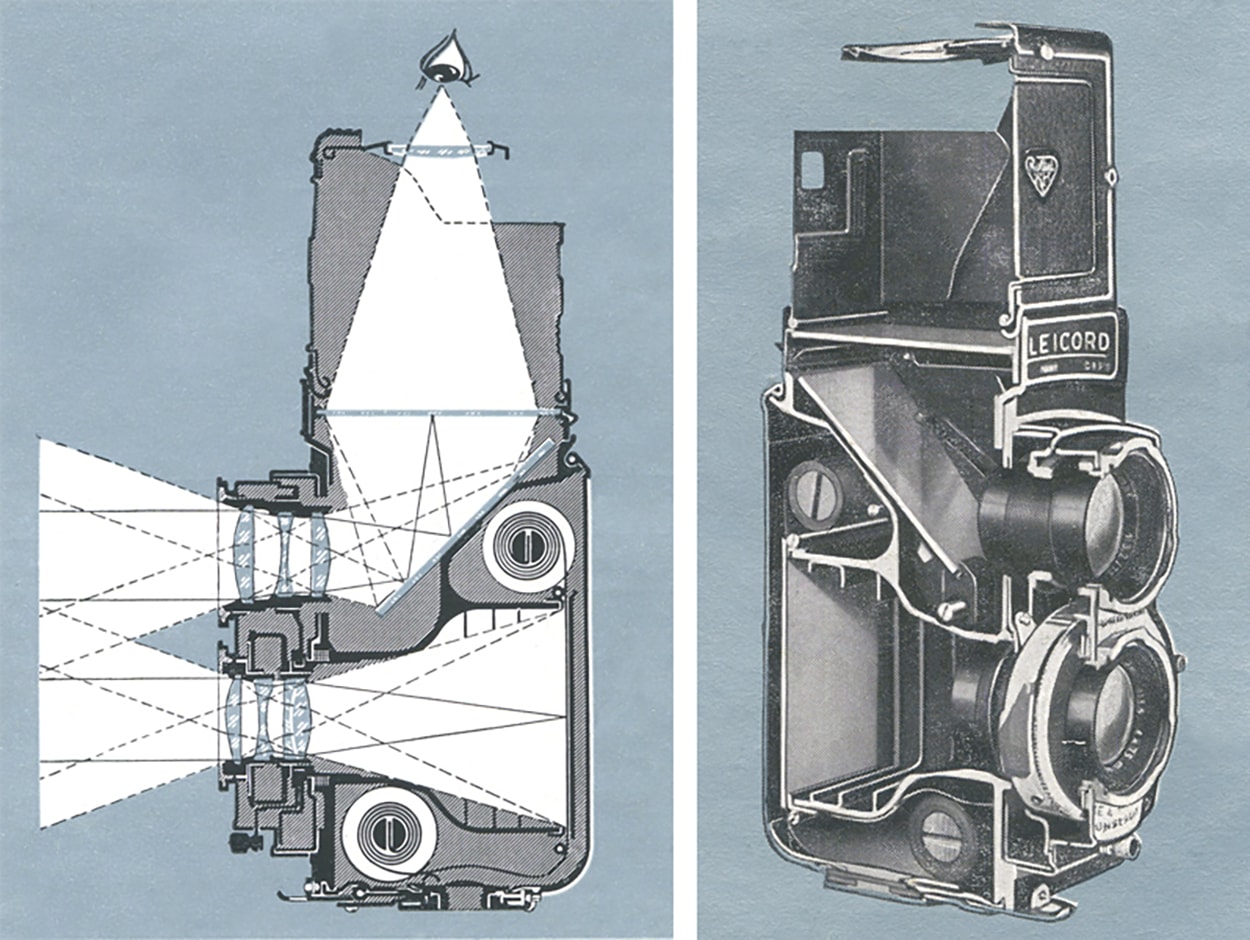

One may surmise that shooting from the hip, in this case of using the viewfinderless camera, facilitates near full-body framing. However, it should be noted that the “black box” of the single-lens reflex camera holds a reflex-mirror assembly viewfinder, a setup requiring that the mirror be moved out of the way after orienting and focusing for the take. This action inside the box is a temporal gap known as “shutter lag.” The introduction of a double or twin lens reflex system to some cameras simplified this process but introduced another level of splitting and distancing of eye from lens. These cameras hold two lenses of the same length, one for the take and one for the viewfinder, which is typically looked into from above with the camera held at waist height. Parallax is a well-known feature of the TLR camera. 10 We add to this the difficulty of judging depth of field in the viewfinder framing, given that the viewing lens has no diaphragm.

Displacement becomes even more pronounced with the introduction of the electronic viewfinder (EVF), through which the lens image is projected electronically onto a (usually tiny) display, in early iterations using a cathode ray tube composed of a vacuum tube and a fluorescent screen. Detached from the functions of the lens and well matched to the frame of the take, the EVF, particularly in the later digital form of the LCD (liquid crystal display), doubles as a source of code and print-form information about the take, bringing to the embodied ocular work of orientation the tasks of reading and computation that in film cameras were conducted through instruments and objects such as light meters and the gray card. An additional point about the EVF is the capability on some models for the flip-out viewfinder screen to rotate, a feature that further dissociates the orientation of the body of the cameraperson from that of the body of the camera and from the field of action that is the object of the shoot. I do not need to bend my body in order to adjust my camera’s point of view; I simply swivel the screen on the ball joint that attaches it to the camera. The flexible LCD viewfinder offers neither the distanced physical relationship of the camera to the body of the photographer made possible by the use of the remote shutter trigger nor the physical proximity of the camera to the photographer’s body demanded by the SLR camera, in which the viewfinder is embedded inside the camera body.

This take on the viewfinder and viewfinderlessness suggests that the two terms exist on a spectrum, and each includes aspects of the other. This account is intended to suggest that multiple precedents may be identified for the contemporary viewfinderless trend in consumer camera technology. With the advent of the LED screen, the camera and viewfinding become more dramatically differentiated as technological processes, each requiring its own bodily relationship to the apparatus. Whether we are considering the camera-body of the photographer using the viewfinderless Brownie or SLR camera, the waist-level work of the photographer of the TLR camera operator who must account for parallax and differences in depth of field, or the photographer who uses the flip-out LED screen of the digital video camera, it is clear that the photographer’s act of seeing has always been displaced in time and space from the camera lens and its line of sight.

We suggest that the displacements discussed thus far may be described as precedents to the design orientation of the newer viewfinderless cameras, which are often mounted to the chest, the ankles, or the wrists of the human subjects whose actions they document, and whose views are managed, if at all, remotely through cell phone or computer screens that are typically sold separately and used elsewhere from the camera. These remote viewfinders may be used to program the camera’s trajectory in advance of a take, but are not always attached to the camera body. There is in this case an added level of displacement, between the time and space of the viewfinder and the camera-body and its lens. The camera’s organizing eye is split off from itself.

We return for a moment to the camera-body of the little boy with a Brownie who “knows more” than classical philosophers—not about the earth but about “what this earth is like.” In this figuration of knowing, we may look for connections between the earliest viewfinderless Brownie camera-body, with its locus of seeing linked not to the eye but to the region of the hips and the genitals, a site of mobility and desire, to the body of the contemporary action-camera wearer, the adventurous person who mounts the camera in multiples to his or her own body parts, documenting all manner of activities, from surfing and climbing to flying and diving. The orientation of the camera, as with the early viewfinderless or attachment-viewfinder Brownie, facilitates not exactly some form of visual knowledge about the world, but rather the physical experience of mobile activity and desire that drives the body toward knowledge, knowing through feeling what the world is like as somatically distributed experience. The camera provides a record of distributed experience, and not a record of what was seen by the eye during that experience. The ocular model of experience no longer holds sway, if it ever did. As noted above, the Kodak advertisement’s wording promotes a view of the Brownie as a phenomenological tool, one that provides experience and the sensation of being in the world in which the eye is displaced from the site of the take, and in which the activity of the lens is just one part of the experience of using the device to experience the world. The feeling of how an experience unfolds for the cameraperson is foregrounded over the idea of the photograph as evidence of what has been. Using the camera in itself is an affirmation of being, an experience that “counts” in the intra-subjective work of the camera-body in the expanded field. Experiments with conditions and processes of experience that entail risk and thrill are especially prevalent in both these camera-model genres of practice, from the early Brownie to the GoPro. The small and portable forms of both camera models facilitate transportability and durability of the camera as always a potential extension of the camera-body in its broadest form, as a human–technological–environmental composite.

We find the concern with the artifact of movement documented in the Cornelius experiment present in the history of the Brownie. Some of the manuals that came with early Kodak cameras cautioned the photographer to “hold your breath” to prevent blur in the image. With the introduction of first the leatherette-covered cardboard case and then Bakelite as the material from which the entire camera body, save shutters and lenses, was made, the Brownie can be interpreted as an earlier iteration of the contemporary action cameras. It is a rugged tool built for experiential engagement and experimental risk. 11 The Bakelite hard casing, a kind of durable media, presaged the hard-body waterproof shell of the Hero action camera line that finds itself immersed at sea, slammed into the ground, and catapulted into space.

Thus far we have discussed examples in which the viewfinder is situated in camera-body ocular displacements in time and place. We have tried to depart from the historical association between seeing and knowing as a key linkage, suggesting instead being and doing as important aspects of seeing and the ancillary work of the camera-body as a source of experience and being in the world. The viewfinder, we now wish to propose, is a kind of interface between user and camera, a point of intra-subjective transit through which the camera communicates what it “sees” through the lens mechanisms inside its black-boxed interior to the camera user appended to the phenomenon outside that box. The viewfinder is a partial space of intra-action in which the user finds his or her points of orientation to the partial idea that the camera portends. The viewfinder is, furthermore, an important symbolic component of the camera-body insofar as it is a visible site of orientation, power, and control. Whether or not we look at the viewfinder, implementing it manually or remotely, the viewfinder-equipped camera-body offers a view. It is therefore not surprising that the viewfinder has come to be debated as a feature the use of which may distinguish professional from consumer-grade camera models, and professional photographers from amateurs. The online forum Quora posed the question “do real photographers still use viewfinders” as opposed to LCD screens? All of the 26 self-identified professional and semi-professional photographers responding said yes, with only the self-identified “reasonable amateur” making the case that the LCD screen offers some advantages over the viewfinder, and one commenter noting that many professionals tether their DSLR to a high-resolution monitor. 12 Knowing how to parse the difference between what you see by eye, what the viewfinder and LCD screen offer, and what you will get through the lens is a key mark of a photographer’s mental expertise. The last comment, regarding “tethering” of the camera to a high-resolution screen, moves us in the direction of mirrorless, viewfinderless cameras, which are designed to produce images to be worked over later, in the form of the image file, on a high-resolution digital editing platform. But for now we remain with the ideology of the viewfinder as signifier of pro-level aesthetics, skill, and identity. The skilled camera-body, in this formulation, is one in which the body of the photographer pines for and seeks out close spatiotemporal ocular proximity and conformity with the eye of the camera. The desire for conjoinment and simultaneity with the lens is an intense marker of professional identity. It is nostalgic of a history we are here trying to counter with snapshots of instances that suggest a subjugated trend toward displacement and uncentered activity in amateur and consumer-driven camera-body relationships and practices.

- Irfan Ahmad, “The Rise of Selfies (Infographic),” Digital Information World, October 20, 2013.[↑]

- “A Brief History of the Selfie,” The Huffington Post, October 15, 2013. For the “word of the year” designation, see the blog post of November 18, 2013, at Oxford Dictionaries.[↑]

- Public Domain Review, “Robert Cornelius’ Self-Portrait: The First Ever ‘Selfie’ (1839),” 2013.[↑]

- Sean Ross Meehan, Mediating American Autobiography: Photography in Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass, and Whitman (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008), 23–24.[↑]

- Quoted in William F. Stapp, Robert Cornelius: Portraits from the Dawn of Photography (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983), 35.[↑]

- On the history of the Somascope and ultrasound, see Malcolm Nicolson and John E. E. Fleming, Imaging and Imagining the Fetus: The Development of Obstetric Ultrasound (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).[↑]

- Nicolson and Fleming, Imaging and Imagining, 33.[↑]

- Greg Siegel, Forensic Media: Reconstructing Accidents in Accelerated Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).[↑]

- Ibid., xx.[↑]

- Parallax is the condition in which the view on the screen is offset from that which will be recorded through the taking lens. The difference between the two views is insignificant for distant subjects, but becomes pronounced when the subject is close at hand, as in a portrait.[↑]

- Peter Lutz, “Beginner’s Guide to Understanding and Using a Brownie Box Camera,” Brownie Camera Page, n.d.[↑]

- “Do professional photographers use the viewfinder or the LCD when shooting with their DSLRs?,” reader query posted to Quora, n.d.[↑]