To the memory of my mother.

When African American pop star Janelle Monáe released her single “Yoga” in the spring of 2015, Indian American bloggers were quick to accuse her of Orientalism and irreverent appropriation. For instance, Sonya Devi on her Bharatanatyam-dedicated Tumblr lamented, “I just cringe watching nonsense like this. Yoga is thousands of years old, and THIS is the Western take on it?” She describes the lyrics “baby bend over, let yo booty do that yoga” as “trash” and asks of Monáe, “Has this girl ever taken a Yoga class, researched what it actually is, or the history and spiritual significance of it? Ugh.” Devi concludes with a caution: “People of color, we are not exempt from cultural appropriation.” 1

While, of course, people of color are not exempt from harmful appropriation, I argue that Monáe’s “Yoga” is not entirely complicit in the kind of generalized “Western” “nonsense” that Devi describes. Rather, I suggest that Monáe’s video – which features the pop star “flexing like a yogi” along with a diverse group of women of color – resonates with Bill Mullen’s provocative inquiry in Afro Orientalism: “Is it possible for Orientalism to do the work of both colonizing and decolonizing?” 2

On the one hand, Monáe appears to perpetuate the commodification of yoga culture in the United States as a profitable athletic pastime or an exoticized spiritual practice, devoid of historical and social context. This version of yoga is largely associated with young, white women. As Rosalie Murphy points out in an article for the Atlantic titled, “Why Your Yoga Class Is so White,” one in fifteen Americans practice yoga and more than four-fifths of them are white. A contributing factor to this demographic disparity is the elitism associated with the practice. Often, yoga classes are expensive, and many studios are located in predominately white and affluent areas in the United States. 3 “Yoga” may be Monáe’s attempt to access this more privileged position, enacting what Helen Heran Jun calls “black Orientalism”: a “discursive means of negotiating the violence of black disenfranchisement” that develops in “structure relation to American Orientalism.” 4 “Black Orientalism,” Jun explains, “is in no way an accusation or reductive condemnation that seeks to chastise black individuals or institutions for being imperialist, racist, or Orientalist. Black Orientalism is a heterogeneous and historically variable discourse” that “encompasses a range of black imaginings of Asia that are in fact negotiations with the limits, failures, and disappointments of black citizenship.” In other words, Monáe may use the dominant white imaginary of yoga as a means for inclusion, as a well as a platform to advance her own pop career. In this case, Devi may be correct and, while different than white appropriation, Monáe may be complicit in stripping yoga from its particularly South Asian “spiritual significance.” 5

On the other hand, Monáe seems to productively diversify the practice, claiming it for American women of color – including South Asian American women – who have been marginalized from yoga as the result of the racial associations and economic factors that shape its commodification. By representing a diverse array of “yogis,” she does not use South Asian culture in the same way as white American yoga studio owners, whose nearly wholesale cultural imperialism has led them to enjoy a monopoly on the practice’s definition, membership, and profit. While she does not engage with, in Devi’s words, yoga’s “thousands of years old” history, she may highlight how the commodification of yoga in United States has historically been geared to white consumers. Moreover, as the video features women with an array of ethnic backgrounds it implicitly refers to yoga’s more global underpinnings, disassociating it with solely India. Indeed, there are yogic movements from across the Asian continent, Africa, and the larger Americas that are often subsumed under mainstream imaginings of the practice. By centering her video on women of color, Monáe untethers yoga practice from white women who are the face of its American incarnation. Dhaaruni Sreenivas, writing in the South Asian magazine the Aerogram, seems to make a similar interpretation, and argues that “Yoga” responds to the question: “What does it mean when women of color take on the stereotypes originally reserved solely for skinny white girls?” 6

These complex significations of “Yoga” challenge its dismissal as Orientalism and appropriation. “Yoga,” in fact, enters into a longer history of Mullen’s notion of “Afro Orientalism,” “a counter discourse that at times shares with its dominant namesake certain features but primarily constitutes an independent critical trajectory of thought on the practice and ideological weight of Orientalism in the Western world.” 7 It invites a reevaluation of appropriation, one that more fully considers the place of race, and particularly blackness, in discourses of authenticity and cultural theft. In other words, Monáe’s music video offers a representation of yoga that does not purport to be ethnically authentic, but is not whitewashed or wholly stereotypical either.

In addition, Monáe genders Afro Orientalism. Afro Orientalism has been an important process for notable black American male thinkers such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King – often with little consideration of its role for black and Asian women. 8 Monáe, however, is part of a pop cultural trend that features black American women creatively engaging with South Asian culture such as yoga or Hindu iconography. I call this cultural borrowing “black goddess politics” to signal the potential, however contradictory, for a crossracial feminism that uses South Asian culture to resist exclusion. Unlike Jun’s notion of black Orientalism, black goddess politics neither defines blackness against South Asianness nor wholly romanticizes South Asian culture. Rather, it has what Homi Bhabha famously describes as a hybridizing function. 9 As black female pop stars translate South Asian culture into different racialized contexts, they challenge the color line by incorporating black women into yoga and Hindu iconography – which have been policed by both the dominant white culture and antiblack South Asians, respectively. As a result, their work resists forms of white supremacy that negatively impact non-black women of color, too. Finally, black goddess politics de-essentializes India’s nativistic and nationalist versions of Hinduism, which tend to be misogynistic and antiblack.

In this popular culture meditation, I first chart the importation and subsequent commodification of yoga in the United States. I outline how Monáe’s “Yoga” acknowledges the practice’s racial coding and the need for yogic “safe spaces” for women of color. I then turn to Hindu goddess iconography, and study the ways in which Beyoncé and Willow Smith engage with Mahādevī, the female deity that serves as the foundation of Durga and Kali, goddesses whose skin color have been lightened over time. I argue that Beyoncé and Smith challenge this colorism within the religion and larger culture, and merge metaphysical constructions of darkness as powerful with the actual skin color of disenfranchised and underrepresented women.

Cultural Theft and Racial Exclusion

In an article for Slate, “‘Where the Whole World Meets in a Single Nest’: The History Behind a Misguided Campus Debate over Yoga and ‘Cultural Appropriation,'” Michelle Goldberg points out that yoga was not “stolen” by white Westerners, but instead has been exported by Indians themselves since the late nineteenth century as a way to undermine Western colonialism. She explains:

Britain’s colonial administrators tended to be contemptuous of Indian religion; indeed, they treated the purported backwardness of Indian thought and culture as justification for their continued rule. Indian nationalists believed, rightly, that if they could popularize their spiritual practice in the West, they would win support for independence. Thus nationalists sent the Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda as a sort of missionary to America, where he introduced yoga philosophy in the 1890s. 10

Goldberg notes that Vivekananda had such a lasting impact on American culture that author of The Wizard of Oz, Frank Baum, allegorizes “the four yogic paths” in the quests of Dorothy, the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion. This popular turn of the century iteration of yoga did not involve the asanas that characterize yoga today; as Goldberg highlights, they are a modern phenomenon, likewise pioneered by Indian men who wanted to carve out a global space for an Indianized notion of physical fitness. Indra Devi, a young Russian woman from an aristocratic background, was one of the early students of the now more popular version of “vinyasa”; Goldberg documents how Devi went on to open the first yoga studio in Hollywood, where she taught starlets Greta Garbo and Gloria Swanson. 11

Yoga’s contemporary appeal has been facilitated by yet another Indian man, Narendra Modi, the right-wing Indian prime minister who had the United Nations recognize “International Yoga Day,” which was celebrated worldwide with global yoga demonstrations. Goldberg concludes: “There was much to deride in International Yoga Day; it served as PR for India’s highly reactionary government and was widely seen as an affront to India’s Muslims. But it shows that the spread of yoga in the West is not just a story about Westerners raiding some pristine subcontinental reservoir of spiritual authenticity.” 12

Goldberg ultimately argues that this Indian participation in American yoga discredits arguments of its cultural appropriation by Westerners. However, she does not fully consider race; the intended audience for yoga in the nineteenth century was specifically white Westerners. As a result, the practice has been so effectively whitewashed in the United States that the anti-colonial impetus that sparked its initial exportation rarely makes it into the American yoga studio and never into a Lululemon store, where yoga pants can cost upwards of eighty dollars. Comedy group College Humor recently lampooned this commodified yoga culture in the United States in a sketch titled “If Gandhi Took a Yoga Class,” in which white instructors chide India’s independence leader for wearing a hand-spun cotton dhoti instead of spandex and for meditating instead of exercising. The sketch captures how far American yoga has come from its anti-colonial underpinnings and its South Asian affiliation. As several African American yoga attendees confess in Angela Tucker’s short documentary Black Folk Don’t Do Yoga, it is most often seen as a way for rich white people to maintain white beauty standards. Indeed, in the eyes of many people of color who feel alienated by American yoga culture’s prevailing whiteness – including Indian Americans – the practice often seems neocolonial. 13

Monáe’s “Yoga,” however, adds to the African-American-led yogic movements for people of color, which resist the dominant white iteration of the practice. For instance, the video recalls Robin Rollan’s Tumblr Black Yogis, which showcases photos of black practitioners and challenges the prevailing image of white women as representative of the practice. 14 And, however unintentionally, Monáe enters into debates about the need for an explicitly racialized yoga practice. Most notably, a Seattle-based studio came under fire for a class dedicated to queer and trans people of color. Local radio personality Dori Monson attacked the class, arguing, “this yoga class is every bit as racist as a bunch of white people who say they don’t want to be around somebody of color.” As a result of Monson’s commentary, the studio’s owner was harassed and received death threats. The class was canceled and the studio temporarily closed. The cofounder of the class, Teresa Wang, indicated that it “was meant to make the practice of yoga – which can make people feel vulnerable – more inclusive, not less.” In a statement for the Seattle Globalist, she said, “The uproar that we have seen is exactly why POCs seek safe spaces such as POC Yoga. In fact, the death threats that we have received are only a reminder of how unwelcome we are among many white people. How could we possibly want to practice yoga in a majority white yoga studio?” Monáe’s “Yoga” imagines a safe space in which she can make yoga an empowered practice of her own, along with like-minded women of color who have not be able to engage with their bodies within the dominant form of the practice. 15

Thus, Monáe’s engagement with South Asian culture goes beyond appreciation – often cited as a slippery counterpoint to appropriation – and offers a powerfully racialized counter to mainstream white American yoga. Indeed, as Nisha Ahuja points out in her video “You Are Here: Exploring Yoga and the Impacts of Cultural Appropriation“:

Yoga is not acrobatic, it’s not aerobics, it’s not a workout, or a good stretch. It’s not competition and it’s not a comparison of one’s being to anyone else or even our own selves. Yoga is a process of coming into yog. And in Sanskit, yog means a “union” … of body, mind, and spirit, and the union of an individual being to a whole being. And to tap into this wholeness allows us to tap into the deep wisdom that lies within ourselves and expand it beyond ourselves. 16

As a result, Ahuja suggests that yoga cannot be taught because it is not completely knowable. It is a process of deep, ongoing learning, not something learned once and understood. She argues that yoga in the North American capitalist context has been turned into something “completely opposite” of yog. It has been “fetishized as something exotic or something attainable, something that can be held … and that’s actually very counter to a yogic philosophy: to renounce possession or to look at how we are attached to wordly things.” She also points out that other global practices from similarly colonized zones resonate with the 5,000-year-old South Asian version of yoga, and cites North and East African Kemetic yoga, the tradition of a spiritual practice by indigenous groups who refer to North America as “Turtle Island,” and the shamanistic traditions in Peru. Perhaps Monáe invites all women of color who have been affected by the different iterations of colonization to come into yog together.

“Seeking Mahādevī”

African Americans have a history of borrowing South Asian experiences and culture to garner political empowerment. Nico Slate documents the longstanding relations between these two groups in his book Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India, and argues that from the late nineteenth century to the 1960s, African Americans and Indians forged bonds based on sympathy and solidarity. He recounts that in 1907 W.E.B. Du Bois described India as “a land of dark men across the sea which is of interest to us … the land, perhaps, from whence our fore-fathers came, or whither certainly in some prehistoric time they wandered.” Slate points out that Du Bois would often “revere India as the birthplace of the ‘Negro race.'” 17 Slate also highlights instances of South Asians identifying with black American experiences. For instance, before Rosa Parks, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya sat in the “whites only” section of a segregated train in the American South. The ticket collector ordered her to move, but she did not. He then asked where she was from, realizing that she was not African American. She answered that she was from “New York.” Slate writes that “at this point, she could have proudly explained that she was a distinguished visitor from India, a colleague of Mahatma Gandhi, and a champion of Indian independence and the rights of Indian women”; she had recently met with Eleanor Roosevelt, too. However, when the ticket collector pressed her about her race, she simply replied that she was “a coloured woman.” Slate suggests:

By refusing to move, Kamaladevi defied the legalized bigotry of the American South. By proclaiming her self “coloured,” she expressed solidarity with the millions of African Americans for whom the brutalities of segregation were a part of daily life. This was more than a fleeting gesture. Kamaladevi understood the efforts of African Americans as crucial to a global struggle against racism and imperialism, a struggled she framed in terms of color. 18

Perhaps the most famous cross-racial borrowing is that of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who engaged with Mohandas Gandhi’s methods of nonviolent anti-colonial resistance, activism rooted in Hindu aestheticism, in order to abolish racial segregation in the United States. In 1959, King traveled to India to see what “the Mahatma” “has wrought.” 19 In an article for Ebony headlined “My Trip to the Land of Gandhi,” King wrote: “While the Montgomery boycott was going on, India’s Gandhi was the guiding light of our technique of non-violent social change.” 20 That same year, King gave a Palm Sunday sermon at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in which he espoused the life of Gandhi as Christian. He told his congregation that, on Palm Sunday,

ordinarily the preacher is expected to preach a sermon on the Lordship or Kinship of Christ … But I beg of you to indulge me this morning to talk about the life of a man who lived in India. And I think I’m justified in doing this because I believe this man, more than anybody else in the modern world, caught the spirit of Jesus Christ and lived it more completely in his life. His name was Gandhi … It is one of the strange ironies of the modern world that the greatest Christian of the 20th century was not a member of the Christian church. 21

King thus folded Gandhi into black American Christianity, which has been a powerful vehicle for survival and resistance against oppressive structures. He productively appropriated Gandhi’s South Asian spirit(uality) to re-envision racial politics in the United States. Moreover, he used his posthumous relationship with Gandhi as a point of departure to imagine a more global solidarity of people of color. In his piece for Ebony, he imagines “a spirit of international brotherhood … with the color of our skins as something of an asset.” Discussing his experience in India, he writes, “the strongest bond of fraternity was the common cause of minority peoples in America, Africa and Asia struggling to throw off racialism and imperialism.” 22

However, most sympathies and solidarities were between men, while women of color were often relegated to the role of domestic backbone supporters: dutiful wives who did not collaborate with each other as directly as their spousal counterparts. In a piece for Ebony, King mentions that his wife, Coretta Scott King, accompanied him on his trip to India and was “particularly interested in the women of India” – an experience that she corroborates in her book, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., but neither she nor King go into specific detail about this interest or her interactions with Indian women. Scott King admits that during a meeting between King and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru where she spoke little, she would have liked to talk “about the women of India … how much progress they had made with the coming of Independence.” She goes on to explain: “As we traveled through the land, we were greatly impressed by the part women played in the political life of India, far more than our country.” 23 Yet overall, Scott King seems more concerned with what her husband gained from the experience; she even recounts that King said to her: “You know, a man who dedicates himself to a cause doesn’t need a family.” 24 She claims that she was “not hurt by this statement”; Scott King says that she believes that King needed her and the children because it “gave him a kind of humanness which brought him closer to the mass of the people.” 25 Spousal loyalty was taken seriously by both Scott King and Gandhi’s wife, Kasturba Gandhi – even when the embarrassing extramarital infidelities both King and the Mahatma remain notorious if hushed.

In contrast to domestic activism, black goddess politics is a markedly feminine and feminist borrowing of South Asian spirituality by African American women for freedom beyond the oppressively gendered duty that is in the service of the explicit “brotherhood” or “fraternity” that King describes. Moreover, it rethinks intersections of gender and race beyond the strict and often racist identity categories of region, ethnicity, and nationalism. It is, to borrow Tracy Pintchman’s phrase, a way in which black American women “seek Mahādevī”:

The unity underlying all female deities and a magnificent divine being … She is portrayed as both transcendent and immanent, rooted in the world and embodying it but stretching beyond it as well, and in some contexts she is identified with ultimate reality … She is both creator and queen of the cosmos and is often portrayed as independent of male control rather than married or subservient to a male consort. Many contexts emphasize her nature as Divine Mother, too, a status that clearly reflects her gender, although she is sometimes said to transcend gender at the highest level. 26

Pintchman emphasizes that interpretation constitutes and constructs Mahādevī’s identity. Her signification is always powerful; unfortunately, it remains mostly metaphysical. It is rarely reflected in the attitudes toward human Indian women, who are often subject to oppressive and restrictive patriarchal practices including but not limited to pervasive rape culture, domestic abuse, unequal opportunity, and lack of education. Indeed, sexist interpretations of the Great Goddess are often mobilized to create hierarchies between human women and men. Pintchman concludes, however, that it is possible for women “to appropriate these images [of the Great Goddess] in ways that are more empowering than the ways in which they have been appropriated in the past.” 27 Departing from the dominant goddess culture of India, which reveres the idol but disenfranchises the women, black goddess politics is this kind of productive reappropriation.

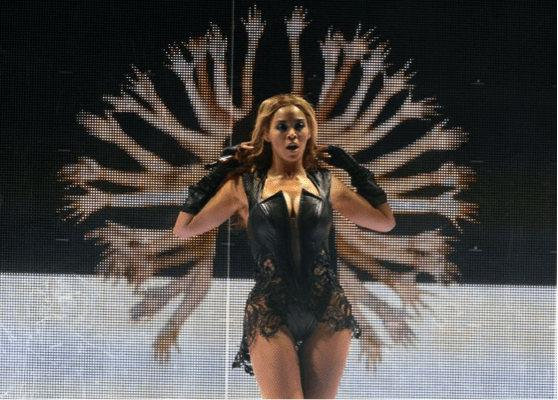

Beyoncé’s 2013 Super Bowl performance in New Orleans, in which she fused herself into an image of Mahādevī, is an example of such productive reappropriation. Theology scholar and priest David R. Henson notes that during that segment of the performance, “there were no male voices and no male bodies in control, only women who refused to be owned.” He argues:

No surprise then that halfway through, the Hindu warrior goddess Durga shows up, incarnated by Beyoncé. Against the pop-up screen, hands emerge and encircle Beyoncé from behind … These are her hands and they reach out and around her, not to possess her but to expand her power. Durga is a fitting image for Beyoncé’s performance, whose name means a fort which cannot be overrun. Durga, the mother, the warrior, the protector from evil. Durga, the female warrior who battles demons, who defeats them. 28

This invocation of Durga is particularly striking given the masculine nature of American football. Her presence was more than part of the show; it was an interruption of the main event itself. The electricity famously went out after her performance, delaying the game, in a moment reminiscent of dark days in the New Orleans Superdome during Hurricane Katrina. However unwittingly, Beyoncé resurrected political demons that should not be forgotten. In light of her allusions to New Orleans in her 2016 visual album Lemonade, in which she engages with goddesses from other cultures such as Brazilian orishas and South African Zulu matriarchs, it seems as if she is still working to “slay” them.

It may be difficult to understand Beyoncé’s allusion to Durga as anything other than fetishistic exoticization given her 2016 feature in Coldplay’s video for the song “Hymn for the Weekend.” Countless writers accused Coldplay and Beyoncé of cultural appropriation, criticizing them of perpetuating a colonial trope that misrepresents India as an exotic playground or Orientalist fantasy. Certainly Coldplay’s positioning in the video, as eager tourists enjoying the festival of holi, consolidates singular narratives about India that romanticize color and song at the expense of Indians’ everyday lives. 30 And this is not their first time appropriating culture for the aesthetic; their “Princess of China” video was criticized for smashing together China and India into one Orientalist landscape. 31 However, Beyoncé’s position in the “Hymn for the Weekend” video as a Bollywood actress is bit different. As Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley and Ntassja Omidina Gunasena for Time argue, Beyoncé actually draws attention to the African presence in South Asia and highlights questions “about what beauty and belonging looks like in South Asia.” In other words, Beyoncé racializes Bollywood – a project that, for instance, Hindi film actress Nandita Das pursues with her “Dark Is Beautiful Campaign,” which points out the Indian movie industry’s clear color line that prefers “fair” skin over “dusky.” 32 This is particularly important given Bollywood’s religious roots; early films recreated Hindu epics, with men playing the roles of women and performing interpretations that espouse the duty of wives and mothers, including that of their outward appearance. 33 Beyoncé’s performance of a Bollywood star engages with this long history, returning women’s bodies to Hindu narratives and challenging their racial representation.

A new generation African American women are productively and provocatively seeking Mahādevī. For instance, Willow Smith, daughter of Hollywood stars Will and Jada Smith, mobilizes black goddess politics in her July 2013 photoshoot with Carine Roitfeld and Jean-Paul Goude for Harper’s Bazaar in which she is fashioned as the Hindu goddess Kalī. The September 2015 issue of the magazine sees “modern-day icons” pose as “history’s legends” which include Hollywood’s famous actresses and fantasy’s female staples. Smith chose a legend outside of that schema; she said: “When I was little, I would go into my mom’s meditation room and read her book about goddesses. Kali stayed with me because she is terrifying, but beautiful.” 34 Blogger eashani dismisses Smith’s interest in her mother’s meditation room, arguing that Smith’s recreation is “disgraceful.” She asks: “How can you can place an actual religious Goddess that people worship next to historical figures like Marie Antoinette and fictional characters like Glinda the Good Witch?” 35 But young Smith’s interest in Kalī draws attention to skin color in Hindu religious iconography; indeed, in the artistic iterations of the goddess, she is black. In other words, like Beyoncé’s incarnation of Durga, Smith’s visual iteration of Kali reminds us that Mahādevī defies the Western color line. That Smith is blue in this particular construction does not negate this reminder. Indeed, as Swami Vivekananda argues, there is an association of infinity with the blue sky, or of the sea. 36 Smith therefore expands herself – much like male gods Vishnu and Krishna, who are also represented interchangeably as black and blue. In contemporary iconography, rarely do female goddesses take on the colored signification of infinity.

What’s more, Smith engagement with Kali has anti-colonial resonances. Hugh B. Urban outlines how Kali signifies “the extreme Orient,” “the most Other, the most archaic or primordial heart of India.” He argues:

On the one hand, the image of Kali in colonial discourse was in large part a mimetic reflection, a projection or everything that frightened British citizens in a foreign land, all the disorder, savagery, and unrest that threatened to unravel the fragile order of their rule. On the other hand, she was a highly ambivalent image, which could be turned around, seized by the colonized, and turned into a powerful – if ultimately unsuccessful – revolutionary instrument. 37

Perhaps most famously, the “Thuggee Cult,” an organized gang of professional robbers and murderers, were seen as a threat to British rule. According to British colonial documents, they were devotees of Kalī – but some historians argue that these sources were prejudiced against the terrifying image of the black goddess and paired her with natives who they viewed as dangerous. 38 The word “thug” has largely been detached from its South Asian roots but is still used in common parlance describe a violent criminal, particularly a black man. As James McWhorter explains for NPR: “Thug today is a nominally polite way of using the N-word … When somebody talks about thugs ruining a place, it is almost impossible today that they are referring to somebody with blond hair. It is a sly way of saying there go those black people ruining things again.” 39 However, in American hip-hop, the word has been reclaimed to describe someone who has overcome hardships – perhaps most famously, Tupac Shakur is adorned with a tattoo that celebrates “Thug Life.” It therefore continues to have shifting signification based on the point of view and action, a linguistic metaphor for the lacuna that divides the powerful and the overpowered. By engaging Kalī, Smith taps into the colonial view of the Thuggee Cult as well as the legacy of the term “thug” in contemporary black hip-hop culture. Because Smith’s interest in Kali extends to yogic meditation as well, it may be that young Smith returns the practice to its anti-colonial history in the West. South Asian spirituality for Smith, as well as for Janelle Monáe and Beyoncé, becomes a form of resistance, one for which the anthem might be Monáe’s words: “I’m too much a rebel, never do what I’m supposed to / Bend it over break it, baby … let your booty do that yoga.”

- Sonya Devi, “Janelle Monáe’s ‘YOGA’ Video – SMH,” Bharatanatyam

Dancers (Tumblr), 2015, http://bharatanatyamdancers.tumblr.com/post/117252861917/janelle-Monáes-yoga-video-smh.[↑] - Bill V. Mullen, Afro Orientalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), xiv.[↑]

- Rosalie Murphy, “Why Your Yoga Class Is so White,” Atlantic, July 8, 2014, http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2014/07/why-your-yoga-class-is-so-white/374002/.[↑]

- Helen Heran Jun, Race for Citizenship (New York: New York University Press, 2011), 6, 18.[↑]

- Devi, “Janelle Monáe’s ‘YOGA.'”[↑]

- Crystal Leww and Dhaaruni Sreenivas.[↑]

- Mullen, Afro Orientalism, xv.[↑]

- See Sanda Mayzaw Lwin, “Romance with a Message: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess and the Problem of the Color Line,” in Strange Affinities: The Gender and Sexual Politics of Comparative Racialization, ed. Grace Kyungwon Hon and Roderick A. Ferguson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). Lwin highlights the ways in which Du Bois constructs a problematic romance narrative in which the lead character, a black American man, saves a South Asian woman from white colonial men, reinforcing stereotypical racializing and gendering.[↑]

- See Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (Routledge, 1994), 121–31.[↑]

- Michelle Goldberg, “‘Where the Whole World Meets in a Single Nest’: The History Behind a Misguided Campus Debate over Yoga and ‘Cultural Appropriation,'” Slate, November 23, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2015/11/university_canceled_yoga_class_no_it_s_not_cultural_appropriation_to_practice.html. [↑]

- Michelle Goldberg, The Goddess Pose: The Audacious Life of Indra Devi, the Woman Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015).[↑]

- Goldberg, “Where the Whole World Meets.” For more on how Indian men have been complicit in commodifying South Asian spirituality, see Vijay Prashad, The Karma of Brownfolk (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 45–66; and Andrea Jain, Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).[↑]

- Irasna Rising, “Why I Left Yoga (& Why I Think a Helluva Lot of People Are Being Duped),” Elephant Journal, July 8, 2012, http://www.elephantjournal.com/2012/07/why-i-left-yoga-and-why-i-think-a-helluva-lot-of-people-are-being-duped-irasna-rising/; Susana Barkataki, “Why We Need Safe Spaces in Yoga,” Decolonizing Yoga, October 21, 2015, http://www.decolonizingyoga.com/why-we-need-safe-spaces-in-yoga/.[↑]

- Robin Rollin, “Black Yogis,” February 1, 2016, http://blackyogis.tumblr.com.[↑]

- Reagan Jackson, “Vitriol against People of Color Yoga Shows Exactly Why It’s Necessary,” Seattle Globalist, October 15, 2015, http://www.seattleglobalist.com/2015/10/15/vitriol-against-people-of-color-yoga-shows-exactly-why-its-necessary/42573.[↑]

- Nisha Ahuja, “You Are Here: Exploring Yoga and the Impacts of Cultural Appropriation,” 2014, https://yogaappropriation.wordpress.com. [↑]

- Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 67–8. [↑]

- Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism, 1–2. [↑]

- Martin Luther King Jr., “My Trip to the Land of Gandhi,” Ebony, http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/documentsentry/590701_my_trip_to_the_land_of_gandhi/.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Martin Luther King Jr., “Palm Sunday on Mohandas K. Gandhi, Delivered at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church,” King Encyclopedia, http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/documentsentry/palm_sunday_sermon_on_mohandas_k_gandhi/index.html. [↑]

- King, “My Trip to the Land of Gandhi.”[↑]

- Coretta Scott King, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Puffin, 1994), 176. [↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- King, My Life, 178–9.[↑]

- Tracy Pintchman, “Introduction: Identity Construction and the Hindu Great Goddess,” in Seeking Mahādevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddesses (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001), 3. [↑]

- Tracy Pintchman, The Rise of the Goddess in Hindu Tradition (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 212–14. [↑]

- David R. Henson, “A Defiant Dance of Power, Not Sex: Beyoncé, the Super Bowl and Durga,” Patheos, February 1, 2016, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/davidhenson/2013/02/a-prophetic-dance-of-power-not-sex-beyonce-the-super-bowl-and-durga/. [↑]

- playbuzz, “How Well Do You Remember Beyoncé’s 2013 Super Bowl Halftime Show?” http://www.playbuzz.com/mtveditorial10/how-well-do-you-remember-beyonc-s-2013-super-bowl-halftime-show.[↑]

- Rashmee Kumar, “Coldplay: Only the Latest Pop Stars to Misrepresent India as an Exotic Playground,” Guardian, February 1, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/feb/01/coldplay-beyonce-hymn-for-the-weekend-cultural-appropriation-india.[↑]

- Paula Young Lee, “Coldplay’s Eat-Pray-Love India: Their Beyoncé Collaboration Is Even More Insidious than Cultural Appropriation – and It’s Not the Band’s First Time,” Salon, February 2, 2016, http://www.salon.com/2016/02/02/coldplays_eat_pray_love_india_their_beyonce_collaboration_is_even_more_insidious_than_cultural_appropriation_and_its_not_the_bands_first_time/.[↑]

- Nandita Das, “When Fair Is Lovely,” http://www.nanditadas.com/nanditawrites30_inc.htm.[↑]

- Tejaswini Ganti, Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2013).[↑]

- Willow Smith, “Icons by Carine Roitfeld and Jean-Pau Goude,” Harpers Bazaar, February 1, 2016, http://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/photography/g6021/carine-roitfeld-icons-0915/?slide=7.[↑]

- Eashani, “The Problem with Bazaar’s ‘Fashion Fantasy’ Photoshoot,” August 1, 2015, https://eashanist.com/2015/08/01/the-problem-with-bazaars-fashion-fantasy-photoshoot/.[↑]

- Swami Vivekananda, The Complete Works of the Swami Vivekananda, vol. 1 (Sri Gauranga Press, 1915), 14.[↑]

- Hugh B. Urban, “India’s Darkest Heart: Kali in the Colonial Imagination,” in Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West, ed. Rachel Fell McDermott and Jeffrey J. Kripal (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 188–9.[↑]

- Cynthia Ann Humes, “Wrestling with Kali: South Asian and British Constructions of the Dark Goddess,” in McDermott and Kripal, Encountering Kali, 155–61.[↑]

- James McWhorter, “The Racially Charged Meaning Behind the Word Thug,” NPR, April 30, 2015, http://www.npr.org/2015/04/30/403362626/the-racially-charged-meaning-behind-the-word-thug.[↑]

- Carine Roitfeld and Jean-Paul Goude, “Icons by Carine Roitfeld and Jean-Paul Goude,” Harpers Bazaar, July 30, 2015, http://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/photography/g6021/carine-roitfeld-icons-0915/?slide=7.[↑]