Art (Click images below to enlarge)

Artist Statement

Last Light: Antarctica

Last Light: Antarctica is a series of photographic works shot in early spring of 2006 when I travelled to the Ross Sea region of Antarctica for two weeks with the Artists to Antarctica program sponsored by Creative New Zealand and Antarctica New Zealand. I arrived one hundred years after the first Antarctic explorers headed off to the South Pole and the centennial celebrations only seemed to me to underline the shallowness, the brevity and the utter inconsequentiality of the colonial project in Antarctica.

The Antarctica I found was an alien icescape—savage and primordial—completely devoid of human objects, huge and oblivious but also replete with signs of fragility, stress and potential collapse. The photographs are at once epic in scale and antiheroic in their attention to the cracks, crevasses, glacier faces and pressure ridges which emerge, collapse and re-form in a rhythm tied to global climate systems that are in turn linked to our own systems of consumption. They point to a dark irony in the growing consensus that while efforts at colonizing Antarctica throughout the twentieth century barely dented its icy surface, our collective addiction to fossil fuels, acting incrementally and from afar, has gnawed deeply into the ice structures that cover the continent. The resulting unintended effect is antiheroic, grimy, disintegrative and potentially cataclysmic.

My photographs borrow their gothic sublime aesthetic from nineteenth century romantic landscape painting and do so to point out a troubling shift in the human relationship to landscape. Edmund Burke regarded sublime nature as awesome, overwhelming, humbling and simultaneously invigorating in its offer of mortality glimpsed but not actualised. The 21st century viewer has an altogether more disturbing relationship to the mountain, the thrashing ocean, the crevasse and the glacier. Now we look at Nature askance and with guilt, aware that its grandeur has become somewhat sullied by our modernity and privilege. What I hope to reinvigorate with this work is the sense of terror that lies at the heart of the sublime response. The large size of the prints gestures to the massiveness and immersive quality of an earlier notion of the sublime. The sense of personal crisis at the center of this former sublime has expanded to include all of humanity. Now when we approach the crevasse we no longer approach the possibility of our mortality alone, but rather that of our species and potentially our biosphere. This is such a terrifying idea that it fails to confer the rewards of the sublime: it does not invigorate. We look askance because we cannot bear to look nature in the face. My hope with this work is to invite that direct look and to mobilize the terror it should provoke.

Polar Gothic

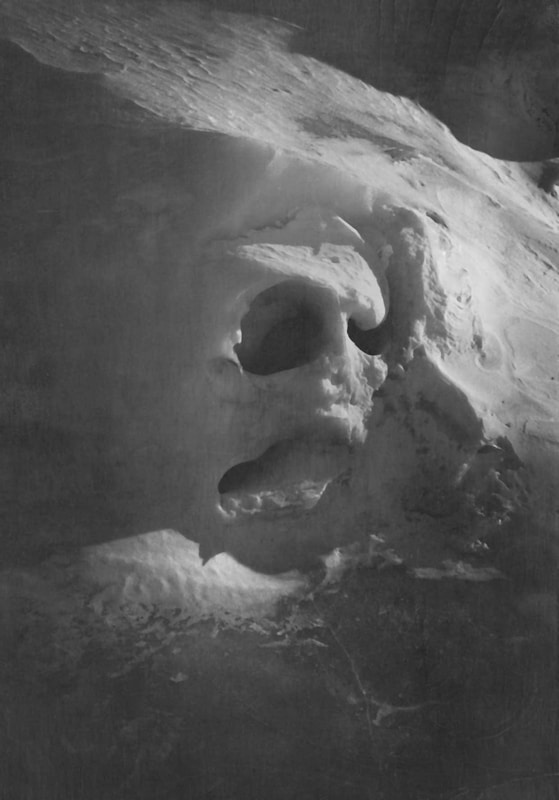

Last Light employs techniques of the past to chart contemporary phenomena that will have enormous effects on our collective future. The daguerreotype is an exquisite technique in which the photographic image floats on the mirrored surface of a highly polished silver plate. I used this technique to document signs in the ice: fissures, flaws, pressure ridges and a screaming ice ghoul, a harbinger that confronted me high in an icefall as I descended though a white out. The daguerreotype requires a direct, physical imprint of light on chemicals on plate that cannot be manipulated or faked through post-processing. In a time of digitized mediation, the daguerreotype offers analog proof of place: it is a sign and witness to the continent’s immanence and of its ruin. The daguerreotype was essentially outmoded by the mid-nineteenth century invention of silver halide emulsion. Because its decline preceded Antarctic exploration, it is a mode of representation that has never been practiced on that continent. In having done so now, I hope to draw my audience into a conversation about modernity and obsolescence and the evidentiary role of photography. Through these anachronistic artefacts I am inviting my audience to invest physically in Antarctica, a place of unrivalled importance and unfathomable strangeness that most of us will never visit but which all of us continuously undermine. The intervention of the “Polar Gothic” into the seemingly tame and managed modern Antarctica of science is a revival of an earlier era’s close relation to terror, but also an embodying of the evil of global warming, which in a change on the daguerreotype’s obsolete force, opens up the volitional aspect of ice, or the way Antarctica reveals itself as a terrifying—and damaged—landscape.

The Dry Valleys and the Futility of the Colonial Effort

On our final weekend in Antarctica our group was flown by helicopter to the Dry Valleys. It was a huge privilege to be taken there, but I was overwhelmed by the trip. It was not until we returned to the base that evening that I began to make sense of why I had found the dry valleys so frightening and why the visit had left me feeling so bereft.

I had walked through one of the most lifeless environments on earth. There was no liquid water and very little ice. The temperature was around thirty degrees C below zero. The stone strewn ground had been worn down by the action of wind over centuries until it resembled a polished tiled surface. I saw no insects, no moss, no algae, nothing green of any kind. There was very little in the way of bacteria. Nothing in this environment could decay. We were admonished not to leave the tiniest scrap of food behind because any remnants of our visit would remain, intact and unconsumed for the next several hundred years. The valleys are littered with the frozen remains of penguins and seals that wandered off course to their deaths hundreds of years ago and have remained there, unchanged, ever since.

There is life in the dry valleys, in the form of nematodes and primitive lichens, but it takes a very trained eye and often the help of a microscope to spot it. It is the kind of primitive, hardy life we might, in moments of great optimism, hope to find on a planet like Mars. And it is in the dry valleys that JPL technicians have found an ideal environment to test-drive their mars rovers, the advance guard in a widely fantasized post-global wave of colonization.

What became utterly clear to me during my visit to the Dry Valleys was the futility of that brand new colonial effort and the essential interdependence of climate and life. We could not have survived more than two hours on that frozen desolate plane without the great stacks of survival gear unloaded with us and we will not survive anywhere else. We will learn to live here or we will die, all of us together. It is not a sublime thought. It is so ugly it can hardly be thought at all.