Land|Slide Possible Futures

In 2010, two municipal councilors, Valerie Burke and Erin Shapero, presented an innovative proposal for one of Canada’s first food belts, which would curtail sprawl in the town—soon to be city—of Markham, Ontario (located northeast of the central city of Toronto in the Greater Toronto Area) for the next thirty years. Especially important was the idea that all development would take place within the boundaries of existing urban areas, encouraging intensification rather than sprawl. The proposal was endorsed by an international community of environmentalists, innovative urban planners, community activists, and the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment. David Suzuki created a YouTube video declaring Markham to be a model for the world, proposing a “bold new direction” that “recognizes that farmlands and greenspaces are priceless” and that they support clean air and water and critical ecosystems (like air and water) that combat the effects of climate change. The land at stake was almost 5,000 acres of Canada’s prime agricultural land that lies between Markham and the designated protected land of the Ontario Greenbelt (at 1.8 million acres one of the largest protected land reserves in the world). A battle was waged between environmentalists and developers. Unfortunately, the proposal for a food belt was defeated by one vote (belonging to a developer) in May 2010.

Land|Slide Possible Futures (2013) was an exhibition conceived in response to this dispute that sought to address the tension between ecology and economy. Organized with urban planner Jenny Foster and education activist Chloë Brushwood Rose, the team devised an exhibition that was much larger in scope than any of Public Access’s previous exhibitions. The larger scope, multiple collaborations, and budget enabled us to invite thirty artists—local and international, emerging and established—whose work had been engaged with ecological issues to help create a collective conversation around the future of land use in Markham. Through a collaboration with Gendai Gallery, we were able to invite artists from China to carry out residencies and spend time in Canada over a period of months, giving them more time for research.

The chosen site for the exhibition was the city’s Markham Museum, a 25-acre open air historical village that included over thirty heritage homes and 80,000 artifacts. The heritage village served as an ideal “laboratory” for this site-specific exhibition for several reasons. The first was that, like The Leona Drive Project, it invited audiences to engage with layered stories of place. Like most heritage villages, it was largely defined by white settler stories of the nineteenth century. Heritage villages across North America were products of the postwar suburb, where they became popular cultural forms, bringing a historical and linear anchor to the “non-place” of the subdivision. Not only were they responses to modernization, but subsequently many houses in heritage villages were relocated due to massive suburban development. Yet, as Alan Gordon has shown, such villages in Ontario also reinforced and provided a highly artificial historical precedent for the CMHC’s suburban ideal of the single-family dwelling on a plot of land. Most of the heritage programs were developed during 1960s and 1970s and featured a gendered division of labor. The layout of the villages mirrored the spatial arrangement of subdivisions; there were no rooms for boarders and itinerant workers, who would have been the dominant labor pool in rural Upper Canada in middle of the nineteenth century. Moreover, women’s domestic spaces, the spaces of childrearing, rather than the production of crafts, were largely the focus of “life” in the villages. Gordon argues that “the visual image of the pioneer village reinforced traditional gender roles as understood by modern suburbanites.” The heritage space created a collective memory that did not so much speak to a past as it did reinforce and idealize the life of the suburban housewife in the postwar era who was its audience. 1

The Markham historical village opened in 1970 and was conceived upon the model of a “living history” museum. The buildings at the museum were uprooted from their original locations and moved to the site, which was designed to look like a nineteenth-century agricultural village. Today, the Markham Museum has evolved into a modern cultural institution, with a new mandate that reflects the contemporary reality of Markham’s diverse population—a population that has little direct connection to its pioneer heritage. The director of the Markham Museum, Cathy Molloy, was interested in the Land|Slide exhibition because it corresponded to her new mandate to introduce ecology into the mix of programs. Markham is the most demographically diverse municipality in Canada, with East and South Asian citizens and other newly arrived immigrants making up more than 65 percent of the population. Markham’s sense of place is infused with diasporic memories and a plurality of cultural experiences brought from elsewhere.

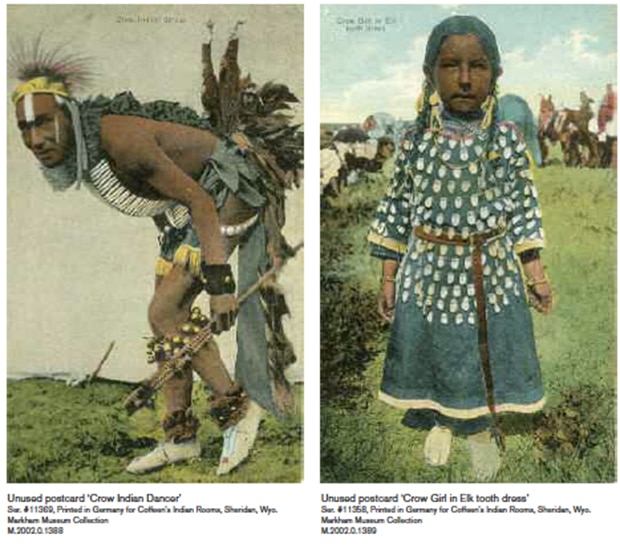

Land|Slide’s artistic probings into possible futures played with the museum’s surreal status as heritage. The museum itself, as one critic has claimed, has the smell of dada because the combination of different styles, which date from the 1820s to the 1930s, and the layout of the village made little sense. As an experiential and experimental platform through which the past may be thought through the present in order to consider the future, the Museum enabled artists to engage with collective memory and notions of futurity. Authenticity was not of critical concern for the artists. Rather, the narrative devices through which history is projected and made to appear through historic buildings and artifacts were central. The projects commissioned for the exhibition essentially moved between history projects and future oriented relational endeavours engaging with ecological issues. Urban-Iroquois artist Jeff Thomas pulled out a dozen postcards of early photographs of First Nations that served as souvenirs, and that were tucked in the museum’s archive. His project was a series of photographs installed on the side of one of the museum’s trains ominously installed on tracks that lead to a parking lot. His photographic series incorporated iconic images of Indians created in the 1920s to sell Canada’s railway industry–on the bottom of each large scale photograph is a question: “Where will go for now…?”

The closed static nature of the photographs and the decommissioned train speak to a nowhere not of utopia but of profound historical failure.

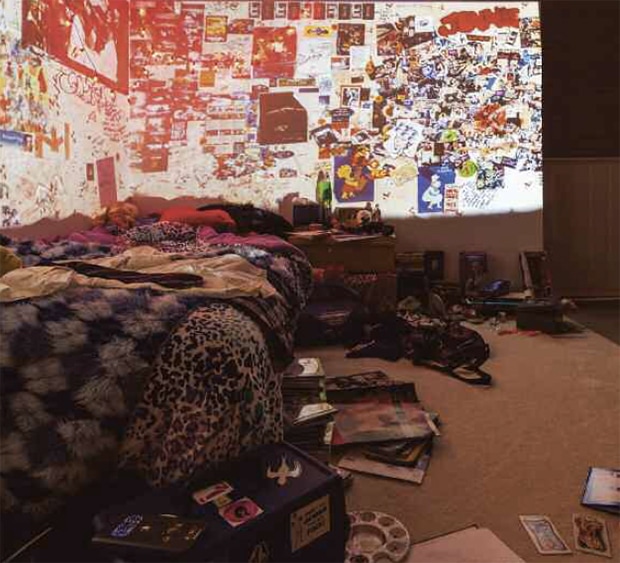

Canadian artist Jennie Suddick, who grew up in Markham, created an anthropology of the teenage girl by transplanting her teenage bedroom into one of the houses; she is interested in generational differences and interviewed both “old-timers” and a younger generation of Markham dwellers about the walks they like to take or remember.

Filmmaker Philip Hoffman’s installation was in the slaughterhouse on the museum grounds and recalled his years working for the family business, Hoffman Meats in Kitchener, Ontario. He presented a series of small-scale projections visible only through the exterior of the building.

Viewers peered through knots in the wood of the barn to witness scenes from the past—but it was a building that didn’t give up its secrets. His installation tells the story of the massive industrialization of the farming industry in Canada, a hidden history of carnage.

Internationally acclaimed Chinese artist Xu Tan carried out several month-long residencies in Markham to understand the Chinese diaspora living there. He curated his own “Chinese pavilion,” featuring members of the Chinese community—Elvis impersonators, immigration counselors, cooks, and garage bands—who created not-for-profit organizations to help newcomers acclimatize to their new home.

On a virtual level, Camille Turner created Time Warp a transmedia walk through the 25 acres of the museum where viewers could follow the adventure of African Space travelers, descendants of the Dogon people of West Africa who left earth 10,0000 years ago and have returned home to save the planet. This a work of pure fiction that invites viewers to imagine the museum as a site of memory where Black lives might be imagined. Turner’s costumes are spectacular and the afronauts can spotted through smartphones using an AR app throughout the site.

Indeed, this exhibition transformed the museum into a robust network—one that is not simply about safeguarding the past through passive spectatorship behind glass vitrines. Rather, Land|Slide Possible Futures opened a gateway between past and future. It created a space of multiple interactions between virtual and real cartographies—from the micrological elements of located stories of migration and indigenous voices to cosmological visualizations of geological data that tell us about our planet in transition. As Grosz’ argues in Chaos Territory, art, following Deleuze and Irigaray, can produce new ontologies, new sensations that enable “the productive explosion of the arts from the provocations paused by the forces of the earth (cosmological forces that we can understand as the chaos, material and organic indeterminancy) with the forces of living bodies, by no means exclusively human, which exert their energy or create, through their efforts, networks, fields, territories that temporarily and provisionally slow down chaos….” 2

This exhibition was an experimental platform, where each installation existed in relation to the other, creating a dynamic ecosystem, and in relation to the site, to the old dislocated buildings whose ongoing care is a constant reminder of our responsibility to history. Grosz tells us that the function of architecture is not to settle on models or utopias but to engage in endless processes of questioning. I’m going to end with the labyrinth that was created by Iain Baxter. This had a very beautiful simplicity to it and was a piece that invited you to wander through it.

The exhibition unfolded over three weeks; it was well attended, with 7,500 visitors. There were numerous symposia inside it, but as with Leona Drive, I’m not yet certain what the impact was. I’m not sure what in fact we changed, except that it happened and it produced a surreal experience that enabled people to reflect on not just Markham, but on climate ecology issues that are going on around the world. The exhibition took the heritage site, which is already strange, and transformed it into something not so much utopian but certainly an embodied and uncanny experience of place, history, and nature. The director of the museum asked me if there is going to be another Land|Slide. No. I won’t do it, but somebody else may. I think what these exhibitions do is begin to create forms—pedagogical forms, artistic forms—that enable these cross-cultural and cross-generational conversations to occur and experimental communities to begin to emerge at a time when new ways of thinking about the future need to be found.