French sociologist Bruno Latour has talked about the incredible career that the term “design” has had: “From a surface feature in the hands of a not-so-serious-profession that added features in the purview of much-more-serious professionals (engineers, scientists, accountants), design has been spreading continuously so that it increasingly matters to the very substance of production. What is more, design has been extended from the details of daily objects to cities, landscapes, nations, cultures, bodies, genes….” 1 Yet because of its history as a decorative art, design has a certain “modesty,” a concern with smaller details, with art and craft, that construction and building do not. Latour goes on to explain that “designing is the antidote to founding, colonizing, establishing, or breaking with the past. It is an antidote to hubris and to the search for absolute certainty, absolute beginnings, and radical departures.” 2 This is so because design never works ex nihilo; it builds upon the past. A designed object always foregrounds its materials, and in this way it is deeply connected to the historical fabric of making.

Surprisingly, there is a revolutionary aspect to design, but not in the more traditional sense of the word. Latour turns to Mao: “the revolution has to always be revolutionized.” Design provides a new set of attitudes that are revolutionizing the revolution: “attitudes like modesty, care, precautions, skills, crafts, meanings, attention to details, careful conservations, redesign, artificiality, and ever shifting transitory fashions.” He tells us “[w]e have to be radically careful, or carefully radical….” In the context of the ecological crisis, design comes at a time when there is much work to be done, “namely the remaking of our collective life on earth.” 3

The significance of design in the contemporary world is tied to the centrality of informatics, computing, and mapping in the daily activities of citizens in global cities around the world. It is tied to the fact that everything can be transformed into information. Indeed, this is what inspired computer designer Lev Manovich to name his latest book Software Takes Command. “Software,” he writes, “has become our interface to the world, to others, to our memory, and to our imagination—a universal language through which the world speaks, and a universal engine on which the world runs.” 4 Manovich’s book is an homage to the 1948 book Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History by the Swiss-born art historian Sigfried Giedion. In the same way that Giedion’s book sought to excavate and analyze the forms of mechanization that helped to give shape to the new industrial society of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Manovich’s book seeks to write a history of those computer programs that we take for granted. For example, he is interested in the programmers and designers responsible for Word, PowerPoint, Illustrator, After Effects, Final Cut Pro, Firefox, Google Earth, and Maya. The value of his book is to be found in this history of software, which is all too often invisible. This book is part of a relatively new field of software studies that will bring a new materiality to our virtual worlds by giving them a historical frame.

Such endeavors are connected to the new materialism that is the subject of Elizabeth Grosz’s book Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Taming of the Earth as well as her book Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics, and Art. 5 She tells us that new materialism provides a new understanding of the forces, both material and immaterial, that direct us into the future. Like Giedion, Grosz believes that artists have a role to play in imagining the world, in the way our worlds are dreamed, designed, and remembered. Grosz reinvents a role for utopia—not simply the functional and spatial utopias of architects such as Giedion or, differently, Le Corbusier; rather, she creates an idea of an embodied utopia. This seems like an oxymoron, since utopias are generally not embodied, but she wants to propose this idea of an embodied utopia that makes room for the other, that makes room for multiplicity and for differences. She also wants to make room for theory and feminist philosophy, to bring them into conversation with the bios. She wants to open a space for the complexity of the world, for its material and political folding.

A central tension in the process of planning capitalist cities is between ecology—the earthly environment—and economy: markets, financial development, and sustenance. The challenge in designing sustainable, livable cities is to move away from conventional top-down approaches to urban planning to incorporate more participatory and inclusive embodied processes in the decision-making. Stockholm-based urban planner Jonathan Metzger argues that artist-led activities can function as a powerful vehicle of communication in the planning process. The unique potential of planner–artist collaborations is based on the artistic license that grants the artist a mandate to set the stage for an estrangement of that which is familiar and taken for granted, thus shifting frames of reference and creating a radical potential for planning in a way that can be very difficult for planners. 6 Metzger’s argument for involving artists in planning may help to open up new possibilities by “shifting frames of reference”; artists make the familiar strange, or, as Russian formalist artist Victor Shklovsky put it, they practice forms of ostranenie—creating modes of defamiliarization that help to distinguish between poetic and ordinary speech. For Shklovsky, “the purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.” 7 It is expressly through forms of defamiliarization that old habits are unmoored and alternative approaches might be rethought.

Metzger is clearly inspired by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas’ “What is Urbanism?” manifesto published in S,M,L,XL (1995) who also advocates that a certain ‘lightness’ be brought into urbanism. He asks designers and architects to relinquish “fantasies of order and omnipotence,” and proposes “the staging of uncertainty” and “the irrigation of territories with potential… enabling fields that accommodate processes that refuse to be crystallized into definitive form.” Instead of being a problem, urbanism needs to “lighten up, become a Gay Science – Lite Urbanism.” It is worth underlining that Nietzsche’s The Gay Science (Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (1882) was his most joyous, cheerful and serious book. It was referencing the Provençal gai saber, the song art of the medieval troubadours who spread poetry throughout Europe. 8

In a similar fashion, Grosz’ argument is that feminist theory and practice has the potential to make us become more than ourselves, in a way to make us become unrecognizable, to make us become strange so that precisely, old habits are unmoored and alternative approaches might be rethought.

With these ideas I want to turn to think about a number of exhibitions that make the familiar strange within an urban environment.

Public Access Collective

Since the late 1980s, I have been involved with the curatorial collective Public Access (PAC) in Toronto, whose mandate is to experiment with and expand the places and forms of what we define as public art. PAC started at a time of unprecedented development in both the downtown core and the outer suburban spaces of the Greater Toronto Area. Working hard to define itself as “world class,” Toronto privatized many of its public spaces (parks and available city spaces) to encourage the building boom of high-rise office towers that has never been matched since that time. PAC was made up of graduate students, artists, and curators who began with the simple question what happened to public space? 9 Based in our reading of the Greek political philosopher and psychoanalyst Cornelius Costeriadis, who gave a central place to the imaginary in the creation of public institutions, our approach was more phenomenological and aesthetic than linguistic or juridical. 10

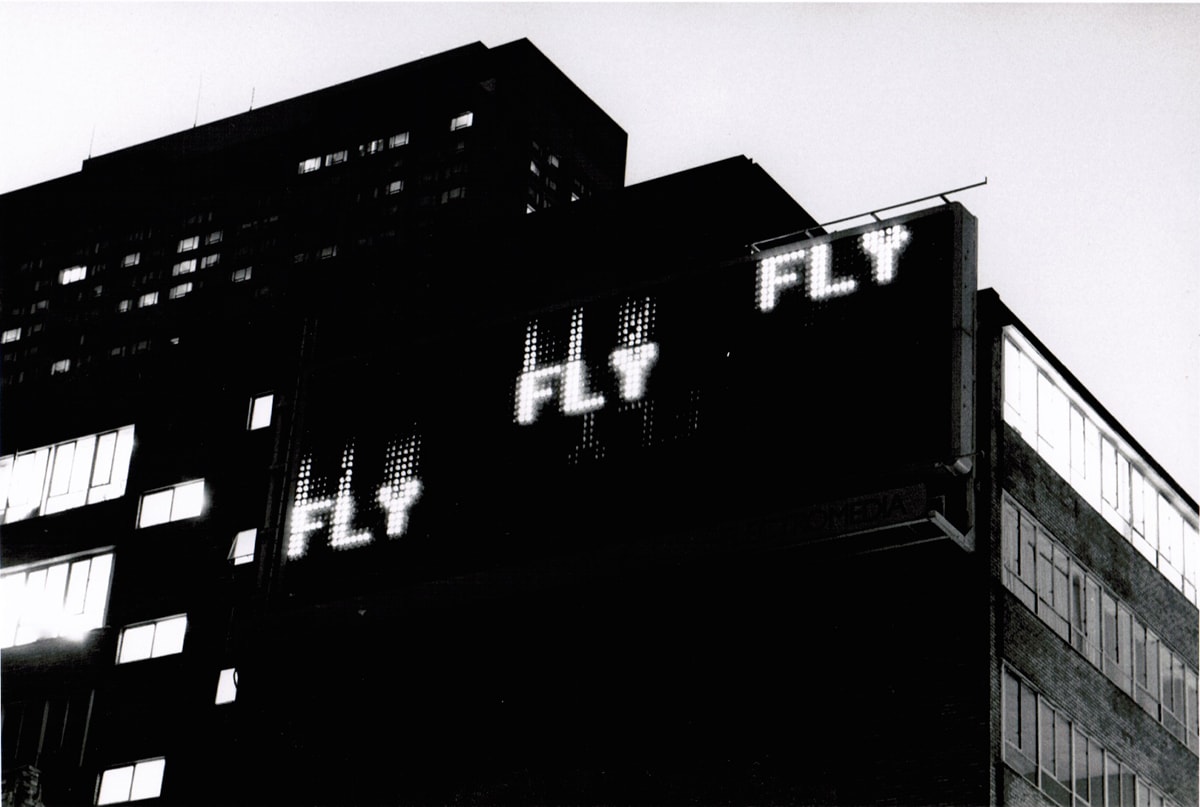

Drawing attention to the privatization of public spaces, our first projects took place in advertising contexts, gaining access (the meaning of public access) to media technologies designed to carry publicity. Some Uncertain Signs (1987) was our first project with seventeen artists invited to create short works for a large Electronic pixelated Billboard sign on Yonge Street—our projects appeared for twenty seconds every three minutes in between advertising; the exhibition ran for six months. Our next project The Lunatic of One Idea (1988) followed a similar format with twenty artists being invited to create video works for the latest advertising technology, a 36 monitor video wall displayed at the newly built Square One Shopping Mall in Mississauga. PAC experimented with new forms of public address in exhibitions that engaged with a range of issues including AIDs activism (John Greyson’s The ADS Epidemic); consummerism (Kryzstof Wodiczko’s Shopaholism video); Vera Frenkel’s video This is your Messiah Speaking); and environmental issues explored by Elden Garnet and Laura Mulvey in different videos. Our exhibitions mirrored other projects unfolding in the US and England that similarly sought to take art out of the museum and gallery, and address the public more directly by taking advantage of new modes of address being innovated by advertising’s public presence. 11 We went on to create public art projects at Union Station in Toronto, and to produce a series of posters created by artists distributed throughout the city. These projects inhabited public spaces in an unfathomable manner, and we have no apparatus for discerning the effects of the interventions. 12

It is telling, though, that with these two projects there wasn’t a lot of censorship, even though the artists were certainly provocative. Greyson’s The ADS Epidemic was played without any hitches. But what was censored by the advertisers, by the advertising company was Wodiczko’s Shopaholism video. The other one that was censored, for the electronic billboard sign project was Lynne Fernie’s textual project “Lesbians Fly Air Canada.” This was very, very contentious for the advertisers and Lynne Fernie (who consulted a lawyer and was told that this statement was true therefore not legally problematic) had to find a language to simply say “Lesbians Fly BLANK Canada.”

The advertisers didn’t want to put the word Lesbians and Air Canada in the same frame in a public space. It shows how far we have come in terms of the visibility of queer culture in public since 1987—the LGBTQ community are a marketing demographic. But both of those art pieces, Wodiczko’s and Fernie’s though very different, spoke to capitalist modes of production (interfered with the marketing of products) and this was the threat. The point I really want to make about these exhibitions is that they were first of all mirroring other exhibitions that were going on in London and New York and we had a lot of the same artists in our exhibitions, artists like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, Victor Bergen, Laura Mulvey, as well as a number of Canadian artists like Michael Snow, Eldon Garnet, Lynne Fernie and John Greyson and so it was a real intervention into the advertising context.

The distinctive zeigest of these projects, and there were other projects that followed through the 1990s (there was a project in Union Station, there were projects on elevator monitors in the financial district etc.) was the parasitic (in Michel Serres sense of the term) relationship to the public sphere. We were not that interested in the public, we were really interested in inhabiting the space itself. We felt that these were successful projects but it never really occurred to us to even think about the public, the public response. That was the shift for us in our curatorial practice that happened in the year 2000 with an exhibition called Being on Time.

- Latour, “A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (with Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk),” in Networks of Design: Proceedings of the 2008 Annual International Conference of the Design History Society (UK), University College Falmouth, September 3–6, ed. Jonathan Glynne, Fiona Hackney, and Viv Minton (Boca Raton, Fla.: Universal Publishers), 2–10, at 2.[↑]

- Ibid., 5.[↑]

- Ibid., 7.[↑]

- Manovich, Software Takes Command (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).[↑]

- Grosz, Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Taming of the Earth (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008); Grosz, Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics, and Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).[↑]

- Metzger, J. (2011). ”Strange spaces: a rationale for bringing art and artists into the planning process”. Planning Theory 10(3): 213-238.[↑]

- Shklovsky, “Art as Technique,” in Literary Theory: An Anthology, ed. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 1998), 16.[↑]

- 1995, 959/971.[↑]

- The founders of Public Access Collective were Christine Davis, Monika Kin Gagnon, Rosemary Heather, Mark Lewis, Janine Marchessault, and Tom Taylor.[↑]

- The Imaginary Institution of Society. Translated by Kathleen Blamey. The MIT Press Cambridge, MA, 1998.[↑]

- We were especially inspired by the different projects of ART/MEDIA which was a social sculpture project that took place in 1986 in Albuquerque and Santa Fe New Mexico involving a series of artist-designed interventions into media: billboards, television, radio and print media. The project also featured museum exhibitions, a think tank, and performance art series. Artists involved in ART/MEDIA included: Hans Haacke, Jenny Holzer, Rachel Rosenthal, Terry Allen and Craig Owens.[↑]

- We also began the journal Public: Art | Culture| Ideas which was a public forum for theoretically informed essays and visual artworks about the public sphere. The journal is still running strong after twenty years. www.publicjournal.ca for more information on the projects and artists.[↑]