Mina hired George Elson, who was of Cree/Scots descent, to be her chief guide and together with three experienced native men they left the tiny fur-trading post of Northwest River, Labrador, in June 1905 to make the six-hundred-mile trip through the interior and north to the George River post on Ungava Bay. This well educated, white, middle-class, very attractive widow of thirty-five, set out alone, with four non-white men, on a journey that would take her far away from all the watchful eyes, constraints, prejudices, and taboos of her society. She would be out of sight (notably by white eyes) for almost seven weeks. However, the Mina Benson Hubbard—elegant, ladylike, demure—as she was depicted in the 1907 portrait by Joseph Sydall (see Illustration 2), was the same person as the happy, free, active woman who strides towards the camera on her Labrador trail in the summer of 1905 (see Illustration 3). Both images were reproduced in her book, and when I reflect on these two images I wonder who the real Mina was and how the free spirit on her Labrador trail managed to squeeze herself back into the corseted, decorous lady. It was reflecting on such apparent contradictions that caused me to start thinking about the concept of invention because the quick answer to my question—who was the real Mina?—is that there were several Minas and that she herself discovered, or invented, some of them during her expedition. The process of invention had begun well before her book appeared in 1908.

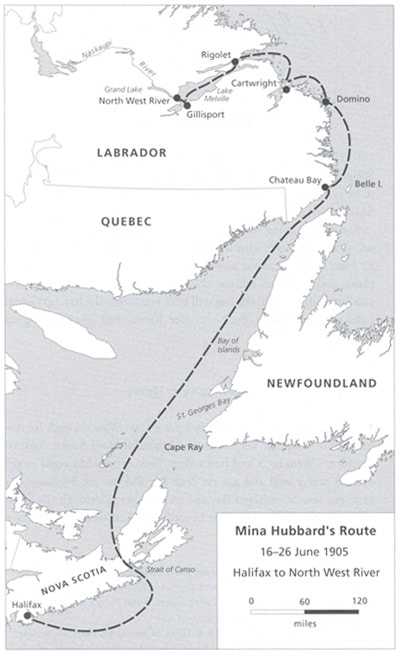

Today Labrador is an official part of Newfoundland, the last province to join Canada in 1949, but at the end of the 19th century it was remote indeed, part of the British Empire, and serviced—minimally—by the British supply ship Pelican which made one annual summer visit to the coast and as far into Hudson Bay as Ungava. The Montagnais and Naskaspi First Nations, now known collectively as the Innu, were virtually untouched by white civilization, and the interior of Labrador had been incompletely, and inaccurately, mapped by Arthur Low of the Geological Survey of Canada. In the racist rhetoric of the day—a rhetoric subscribed to by most northern explorers but not by Mina—these tribes and their way of life were objects of curiosity, the stuff upon which to make a reputation, stone age people for white men from the south to discover. One of the key reasons for the failure of Leonidas’s 1903 expedition was the map; he could only rely on Low’s partial and inaccurate cartography and he took the wrong water route. Among the other reasons for his failure and death were his lack of appropriate supplies and gear, an early winter, and an unwillingness to listen to the advice of his non-white guide George Elson. Mina made none of these mistakes. She set out, as Leonidas had done (and as Dillon Wallace was doing again at exactly the same time, in June 1905), from the Northwest River post, she found the correct river route up the Naskapi River to Lake Michikimau and then north on the George River to Ungava (see Illustration 4). As she went, she took the measurements that enabled her to redraw the map of the Labrador interior; she took hundreds of photographs of the country, its native people, her guides, for whom she had the utmost respect, and their expedition work; and she wrote almost daily in her journal. She did not have to do any of the heavy, dangerous work of poling, packing on portages, or paddling, but after her return unknown Labrador was unknown no longer. Contemporary maps of Labrador and Atlantic Canada provide some sense of how the area looks now (see Hart et al); however, a mere map cannot capture the significant changes that have been made from the time of WWII to the present by white settlers, developers, and politicians.

Mina would go on inventing herself after her return from Labrador by giving public lectures, writing essays—scientific and popular—and publishing her book. She remarried in England, raised three children and worked for the suffragette movement; she returned to Canada frequently and once, in her sixties, traveled north for a reunion with George Elson. Labrador had become part of her, as the announcement for a 1938 lecture indicates: the lecture, given at today’s University of Guelph was part of a tour she undertook that year and she is described in the advertising as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and as the successful explorer of Labrador (see Hart, 411). According to her children, she was an austere presence who would regularly set forth on long walks by announcing that she was going off to explore, and it was on the last of these explorations that she was struck and killed by a train, not far from her home in England, at age eighty-six. Today a commemorative plaque has been erected beside the road in front of the original Ontario farmstead where she was born and grew up, but that is only one visible reminder of who she was.