This article is reprinted with permission from Nordlit 22 (August 2007): 49-69. It has been revised.

In November 1905, Mina Benson Hubbard recorded in her expedition diary that she had “accomplished all that [she] started for.” 1 But she had not quite accomplished everything she wanted to do, and the expedition she had successfully completed would never leave her mind; it had changed her, made her over from a genteel wife and widow into an explorer and an author. Even before she began her journey, Mina (as I call her now after my long association with her) knew she wanted to make maps, take photographs, and write a book. She started her book while still in Labrador waiting for the supply ship that would take her back to civilization, and as she confided to her diary on August 31st, 1905: “Writing to-day. Slow. Hard to decide what to write about . . . wish I knew a bit better what public is interested in.”

I have begun my discussion with these brief snippets of Mina speaking privately in her own voice because this is about as close as we can now get to the woman who lived at the turn of the last century. When I began my work to prepare a new edition of her 1908 classic, A Woman’s Way Through Unknown Labrador, I knew I wanted to do my best to recover this woman, but I also quickly realized that the task was impossible and that what I would actually end up doing was to invent a person I call my Mina. But before I say more about this process of invention, I must provide some biographical background about the woman and her expedition and some factual information about Labrador.

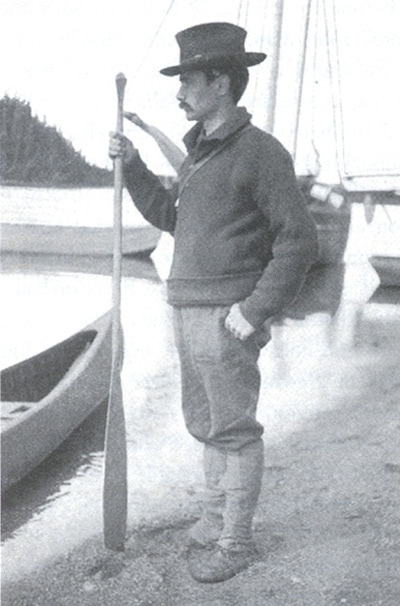

Mina Benson was born in 1870 into a comfortable Irish Protestant family in southern Ontario, Canada. She grew up on the family farm with her seven siblings, and as a young woman she had already developed an appreciation for the outdoors and a strong sense of independence. She left Canada for New York City to train as a nurse, a move that was not common for women of her class and period; however, nursing was, like teaching, an acceptable profession for an unmarried woman. It was there that she met her first husband, Leonidas Hubbard, Jr. Both she and Leonidas enjoyed canoeing and camping, recreation activities that were becoming popular at the time, but Leonidas had more ambitious plans. He had decided to lead an expedition into one of the last unknown (to white explorers), unmapped, and unphotographed areas of North America—the vast interior, northern territory of Labrador—so that he could write about his adventure (see Illustration 1). Sadly, he starved to death on his 1903 expedition, which was a miserable failure in many ways, but his intrepid guide, George Elson, made it to the nearest settlement for help and was able to save himself and the third man on the expedition, Dillon Wallace.

Mina and Leonidas had only been married for a few years; they were deeply in love; and she was left behind waiting for news that took many months to reach her. When it did, she was devastated by her husband’s death. To make matters worse, Dillon Wallace quickly published his account of the expedition. Mina was outraged by his portrayal of her beloved Laddie and immediately decided to mount her own expedition—the second Hubbard Expedition—so she could complete his work and rescue his reputation. 2 However, her husband’s family was violently opposed to her plans; Wallace, who also planned a second expedition, was hostile; and as soon as the press of the day learned about her expedition they went berserk—but I will get to these early 20th century papparazzi in due course.

- All quotations from dated entries in the journal that Mina kept during her voyage can be read in Roberta Buchanan’s transcription published in The Woman Who Mapped Labrador; see Hart, Buchanan, and Greene.[↑]

- For a discussion of Wallace and of Mina’s plans, see my introduction to A Woman’s Way, Hart’s biography, and Johnstone’s analysis of Wallace’s American ideology.[↑]