*Reprinted with the permission of Duke University Press.

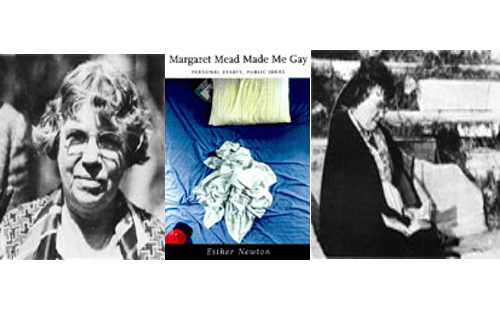

Reading Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa was my introduction, not only to the concept of culture, but to the critique of culture – ours. Before 1961, when I read Coming of Age in an Introduction to Anthropology course at the University of Michigan, Mead had already done a great deal to popularize the concept of cultural relativity. Her voice had reached into my teenage hell, to whisper my comforting first mantra, “Everything is relative; everything is relative,” meaning: There are other worlds, possibilities than suburban California in the 1950s. I was a scholarly minded half-Jew from New York (where I had spent my childhood) and a red diaper baby. I was athletic, hated dating boys, and resented pretending I was less of everything than they were. Neither girls’ clothes nor girlish attitudes felt “right” to me. And I was attracted – in some sweaty way that had at first no name – to girls and women.

College in Ann Arbor was better, but still found me unhappily struggling to fit into a slightly more sophisticated workup of American womanhood. I was looking for any way out, some Mad Hatter to lead me down a rabbit hole into a world where I didn’t have to carry a clutch purse and want to be dominated by some guy with a crew cut and no neck. Having these thoughts was, however inchoately, a critique. Acting on them constituted rebellion. Calling myself gay, which I had done tentatively and with self-loathing at sixteen, moved opposition to a higher level. Anarchism, I read once, is an ideology of permanent rebellion. Anthropology, by refuting any one culture’s claims to absolute authority, offers a permanent critique. So when I read Coming of Age in Samoa my senior year in college, I was, to put it mildly, receptive.

Through Margaret Mead I grasped that my adolescent torments over sex, gender, and the life of the mind could have been avoided by different social arrangements. It’s not that I imagined a better life in the South Seas. I was far from fancying myself in a grass skirt (despite becoming an anthropologist, I am a homebody; the rigors of long lonely stays in places without electricity and flush toilets only appealed to me, as it turned out, in books). Even though Mead’s Samoan girls were happily exercising a heterosexual openness that I had found unsatisfying, the setup was so radically different – multiple parenting, sexual freedom – from what I had been convinced was normal and right. Mead’s work taught me that the smug high school peacocks whose dating/popularity values had rated me so low, reduced me to such a nothing, were not lords of the world but only of one nasty barnyard.

The kind of cosmopolitanism that is anthropological knowledge is a dangerous thing to tyrants. I once heard a German woman say that the worst damage the Nazis did to young people in the 1930s was to censor knowledge of alternatives, so that young Germans had no point of comparison. I knew nothing about Margaret Mead’s being bisexual, in fact nothing about her, period. (I would not meet her until years later, and then my contacts with her, though significant to me, were fleeting.) Nor is Coming of Age in Samoa an overt defense of homosexuality. But it is a defense of cultural and temperamental difference, and that, despite my desperate attempts to go with the flow, described me: different.

If Margaret Mead opened the world of anthropology to me, the sheer fact that she was a woman and chose women as subjects was just as important. I first encountered versions of the other worlds that anthropologists explored in the science fiction of such writers as Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov (there are strong resemblances between the two genres, made most explicit in the work of Ursula LeGuin, the daughter of an anthropologist). But Heinlein’s and Asimov’s universes were male and straight. I could only imagine myself into their settings as the macho guy I’d always been ashamed of wanting to be. Though their books were wonderfully escapist, they didn’t provide the scripts in which I could star as any kind of woman. (Something similar could be said of the philosopher Spinoza, about whose work I wrote an admiring high school paper.)

I had come to college with the intention of becoming a psychologist like my father, but reading Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture reset my course. Perhaps, in retrospect, the examples of such intellectually powerful women gave me the courage to strike out on my own. I studied and was deeply influenced by literature and then European history. But as a graduate field of study, history promised a life of isolation in the library. I was a misfit whose relationships were troubled because intellectuals are not popular or respected, because women intellectuals back then were weird, and because I was a tormented, closeted queer. Anthropology, I thought, would force me to get out and interact with people, as Margaret Mead had done. And as it turned out, through anthropology I became an activist intellectual, like Mead, dedicated to education and reform. My chosen life work . . . has been to chronicle and champion the lesbian and gay cultures in which I have found both a home and ever-compelling subject matter.

However, my relationship to the organized profession has never run smoothly for a number of reasons, not least among them the entrenched homophobia of academic anthropology. “Go into anthropology,” I was told as a college student. “You can study anything you want.” As it turned out, I took that advice further than anyone, including me, expected, further certainly than the majority of anthropologists approved. As explained in several of [my] essays, notably in “Too Queer for College,” my academic career almost foundered early on and has been blocked both indirectly and at times aggressively at every stage of advancement. Without the organized support of feminists at Purchase College, where I have taught since 1971, I would have been expelled from academia in 1973. So I looked instead to lesbian-feminism for support and later to the gay community, or more specifically, the growing network of lesbian and gay intellectuals. Yet my true vocation as a writer has been nurtured and sustained by anthropological ideas, and this collection records the intellectual journey into which I was seduced, not by Margaret Mead in person, but figuratively by her, in every lovely sense of the word figurative.

The excerpts and essays [in Margaret Mead Made Me Gay] constitute an intellectual autobiography. They begin with sections from Mother Camp (1972), my first published work, based on my dissertation on drag queens, and continue until the present. Frustrated by how little of my writing had been published – until the mid-1980s, neither academic nor popular venues were receptive – I first conceived of putting together a book of my essays in about 1988. At that time fewer essays than at present were organized chronologically, including some fiction that I had written in the 1970s. My all-consuming focus on the book that became Cherry Grove, Fire Island (1993) precluded further progress on this collection, and I didnÕt come back to it seriously until 1994, after the Grove book and several essays derived from the Grove fieldwork had been published.

My longtime friend Jeffrey Escoffier, who had edited the journals Socialist Review and Outlook, agreed to go over the essays and suggest some form of organization other than just chronological. Looking for distinctive themes in my work, he suggested three alternative schemas that ranged from combining essays with a lot of new autobiographical writing to a minimalist collection of perhaps ten essays. The current organization into four broad topics is derived from one of Jeff’s outlines and is a hybrid of chronological and thematic principles of organization. I did begin the autobiographical writing that Jeff had proposed in 1996 after an invitation from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the City University of New York to give the annual David R. Kessler lecture, which became the essay included here, “My Butch Career.” By then there were so many essays that setting them in a memoirist frame seemed too unwieldy. (I have decided to expand the material in “My Butch Career” into a separate, book-length memoir.)

The four broad topics of drag and camp, lesbian-feminism, butch, and queer anthropology do not all correspond to periods in my career that came and went. Rather, they represent the constellations by which I have steered my intellectual life through the currents of time and the phosphorescence of personal experience. They signify my preoccupation with the theatrical and political symbols that designate and shape queer American life, albeit in very different ways, for both gay men and lesbians, including myself, as some of these essays show.

The reasons I write anything, why I chose to write about Cherry Grove, for instance, are the same as those for any human action: to be found in culture, history, personality, and chance. Some factors are imposed externally, as when my then-partner and I were harassed by young boys during a Catskills vacation and so sought safety in the gay beach resort. Others well up from a deep internal aquifer. Drag and camp dramatize the “gender trouble” that has shaped me from the first; theatricality delights and excites me, period.

Part 1, Drag and Camp

Gay theatrical cross-dressing and the sensibility that usually accompanies it were the subjects of my first big anthropological project. Mother Camp was based on several months of fieldwork in American cities, as described in its appendix. “Role Models,” the best-known chapter from that work, has been reprinted several times, and my reason for including it here is its foundational position in my own work and in that of a number of other scholars. Mother Camp itself laid the groundwork for the anthropology of homosexuality, especially the branch that is the study of the cultures of queer people. In the melancholy preface to the 1979 reprinting of Mother Camp (included here hesitantly, because it takes an unnecessary swipe at practitioners of S/M, about whom I then knew little) I publicly swear off drag and camp, obliquely re-flecting my disappointment over my book’s lack of recognition within anthropology. Yet, after taking up residence in Cherry Grove in the mid-1980s, I fell for gay men and their dominant cultural forms all over again. “Theater: Gay Anti-Church” was originally to be a chapter of the Cherry Grove book, which it outgrew. Another Grove-based essay, “Dick(less) Tracy,” explores the relationship of lesbians to drag and camp, an issue I had mentioned only in a footnote in Mother Camp.

Part 2, Lesbian-Feminism

My climb up the academic ladder was disrupted not only by the unconventionality of my first book on female impersonators and the gay subculture, but also by the historical intervention of the Vietnam War and second-wave feminism. All but the last of these essays were written in the period between 1971 and 1973, when the feminist firestorm was crackling through my mind and heart. Although I had been changed forever by the time the fire died down, part of the transformation was burnout and partial disillusionment with ideology and social movements.

The first four essays in this section reflect a revolutionary feminist rethinking of my life to that point. I could have called the section “Feminism and Lesbian-Feminism,” but that seemed awkward. I became a feminist during the winter of 1968; certainly by 1971, when “The Personal Is Political” was written, I had become a lesbian-feminist. That essay, though in an “objective” mode, is a collective portrait of my middle-class generation’s tumultuous experience in consciousness-raising groups. The excerpt from Womenfriends, a joint journal written with Shirley Walton, who was and remains my chosen sister, records painful attempts to integrate the lesbian-feminist I had become with the rest of my life.

Lesbian-feminist separatism, which I had once ardently supported, had evolved by the late 1970s into something too much like a cult, and finally degenerated into the antipornography movement, whose alliances with the Christian Right were utterly repugnant. This disillusionment is most strongly reflected in “Will the Real Lesbian Community Please Stand Up?”; the first draft was written for the annual anthropology meetings in 1984. This essay was among those that marked my return to social science work after more than a decade of disaffection.

Part 3, Butch

Beginning in 1981, I attempted to deal personally and intellectually with my lack of femininity (to that point having shied away from calling it “masculinity”). “The Misunderstanding” came out of a talk that Shirley Walton and I had given at the famous 1981 Barnard Conference on Women’s Sexuality, a watershed confrontation between the “pro-sex” feminists I sided with and the antipornography feminists that marked my decisive rejection of lesbian-feminism. In the years after the conference I set to work on the essay that eventually became “The Mythic Mannish Lesbian,” a reappraisal and rehabilitation of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, and the first of my work to be published by an academic, albeit feminist, journal. Its positive reception encouraged me to take up scholarly work once more.

I would also like to think that “Mythic” built on whatever influence Mother Camp has had in encouraging the emerging transgender movement composed of transsexuals, the intersexed (hermaphrodites), cross-dressers, nelly queens, and butches and femmes that grew from and intersects with the gay and lesbian movement. Lesbian-feminism, despite its (by now quaintly refreshing) militant opposition to capitalist “patriarchy,” had submerged sexual and gender nonconformity into one big proposition: women are oppressed by men. But even an idea as momentous as that one canÕt explain everything; the world is just too complicated and there are too many vectors of domination going at once. My own experience and the research on Mother Camp taught me that not everyone lines up obediently on the boy/girl grid. During the 1980s I reflected more deeply about the gender grid itself, as the book review reprinted here, “Beyond Freud, Ken, and Barbie,” in which I evaluate some of the social science literature on gender, attests.

My enduring involvement with butch issues is the flip side of my love of drag and camp, except that the butch essays track how I came to identify myself as butch and to become slowly but steadily more public about it. The third-person voice in “The Mythic Mannish Lesbian” is still separate from the first-person voice in “The Misunderstanding,” published the same year; “My Butch Career” makes my lifelong relationship to issues of gender dissidence personal and explicit.

Part 4, Queer Anthropology

About 1980 I became active in the Anthropological Research Group on Homosexuality (now the Society of Lesbian and Gay Anthropologists in the American Anthropological Association); our goal was to provide a safe space for queer anthropology and anthropologists and to challenge the entrenched homophohia we had encountered. . . .

Coming of age politically during the antiwar movement, I had a jaundiced view of capitalism, but as Gayle Rubin once pointed out to me, despite its terrible injustices, capitalism is not all bad, and the one institution that has changed more than any other in response to the demand created by a queer reading public and queer students is publishing. Never will I take for granted how gratifying it is to be published and to have people read and respond to my work!

Which brings me back to Margaret Mead and to Ruth Benedict. Both of these brainy women (in common with Gertrude Stein, who, as “My Butch Career” reveals, was the third of my idols) were not only good writers, they were versatile writers. They aimed to engage both the cognoscenti in their fields and a general literate readership. They went where their interests and talents took them rather than sticking to the academic straight and narrow. Mead even wrote in the mass media and appeared on television; Benedict was a poet. As women and as sexual iconoclasts, Mead and Benedict were partial outsiders to the insular world of professional anthropology, and they both believed in influencing public opinion to promote social justice. It is to this tradition that I aspire in the hope that both the general reader and the student of anthropology will find pleasure, interest, and inspiration in these pages.

October 22, 1999

New York City