Are the new reproductive technologies, in particular, which aim towards “improving” reproduction with a range of high-tech interventions, unavoidably eugenicist? The answer is complex. On the one hand, many of the technologies (gamete donation, especially) are advertised and used within a blunt discourse of “custom-building” ideal babies, selecting the “fittest” eggs and sperm from young, healthy, attractive and talented people, and trading on the long-standing science fiction/fantasy that the complex traits and accomplishments of the donors will be passed to offspring through the donor’s DNA. Two of the artistic entries in this issue—Critical Art Ensemble’s (CAE) Flesh Machine and the exhibit of pieces by the subRosa Collective—capture the enticements of glamour, human perfectibility, and the promise of a clean, bright future that propels the idealization of science in this discourse. The racialization of “high quality” humans is unavoidably white in this future, a point made in a no-nonsense way by subRosa’s “Calculate Your Fleshworth” worksheet, which assigns specific values to your eggs or sperm based on your race. The eerily white fantasy future projected by the imaginary “bioCom”/Flesh Machine (CAE) corresponds all too well to the visual promise of white babies made by the websites of real-world companies advertising surrogacy services (even where the surrogates themselves are brown, as Waldby describes).

And it’s not just the sellers of services and materials in the reproductive market that imagine a future of whiteness. In a beautifully empathic and complex ethnography of clients of an IVF clinic in Dubai, Marcia Inhorn relates the tale of “Eyad,” a Palestinian man who longs for (and apparently manages to obtain) the eggs of a white donor he glimpses in the clinic. “In the future,” Eyad tells Inhorn, “all people will look like they are Americans!” 1 Eyad’s longing for eggs from the “American-looking” donor is connected to his status as a foreigner and history as a refugee, and it plainly articulates the connection of race, national belonging, and transnational mobility:

‘I hope my wife gets some eggs from that girl, because my child, she’ll be coming white—already American!—and not black like my wife.’ He added, facetiously, ‘My child, when he comes, he will take the American passport in the future.’

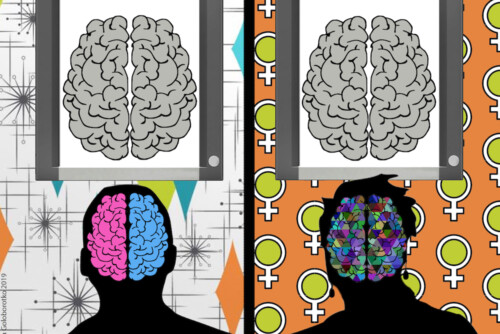

Should we call Eyad’s longing eugenicist? Again, the answer is complex. Historically, eugenics stemmed from a position of anxious privilege: economically well-off white people concerned about a perceived loss of control and a potential loss of authority and status. Hierarchies embedded in discourse about reproduction of “the fit” did and still do coincide with people’s own hopes and plans for offspring that would make them proud—but the alignment is sometimes a queer one. The queerness comes from the difference between the message of dominant discourse, and the conditions of its reception, most specifically including one’s relative position of privilege. 19th century middle-class whites were concerned about degeneration: evolutionary “backsliding” and “race suicide” seemed to threaten the privileges they enjoyed and wished to secure for their heirs—among whom they counted the “future nation” and “the (white) race.” In the present, “successful reproduction” for the privileged may similarly aim to prevent downward economic and social mobility in an environment that is perceived as more highly competitive and pressured than ever. I think it is right to name as eugenic this “defensive” reproduction of the privileged—even when it is practiced on a small scale rather than as a matter of social policy, and even absent a conscious disavowal of “unfit” race, class, sexual, or bodily types. But for people who are economically, socially, and/or politically marginal, strategies for “successful reproduction” may draw on the same hegemonic values (regarding race, ability, gender, sexuality, and so on), but they can’t ever be properly “eugenic” because their aspirations for upward mobility involve a breach of the fundamental purpose of eugenics: the reproduction of existing hierarchies.

Sorting individual technologies or their users into “eugenic/eugenicist” or not is, however, not the point. Instead, it is useful to be alert to the potential these technologies have for (re)animating some of the most pernicious modes of ranking human types and traits. Questions we might return to again and again include: Whose reproductive futures are highly valued, and whose are discounted in the global reproductive market? How are specific technologically-assisted reproductions built on those hierarchies, and how do they revitalize the habit of ranking people and traits, as well as the specific content and order of the hierarchies? How and when do reproductive technologies disrupt the eugenic goal of reproducing hierarchies? For example, a wide range of reproductive technologies are used to facilitate reproduction among LGBT people, who are both historically and currently “disfavored” reproducers by the dominant schema. Sperm washing, chemotherapy during birth, and cesarean sections enable reproduction among HIV+ women and men, though the dominant expectation is that HIV+ people “should not” reproduce. As Gwendolyn Beetham’s exploration of first-person accounts from queers and infertile heterosexuals suggests, reproductive technologies can and do “queer” reproduction, even as they simultaneously reinforce certain normative assumptions, such as the privileging of biological over adoptive parenthood.

- Marcia Inhorn, “‘Assisted’ Motherhood in Global Dubai: Reproductive Tourists and Their Helpers,” in The Globalization of Motherhood: Deconstructions and Reconstructions of Biology and Care, Wendy Chavkin and JaneMaree Maher, eds. (New York: Routledge, 2010): 194.[↑]