Over the past five years, there has been a resurgence of resistance, awareness, and action around police violence, sparked by the August 2014 killing of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson, and the subsequent uprisings that spread in waves across the country to New York City, Baltimore, Baton Rouge, Minneapolis, and beyond, consolidating into the Movement for Black Lives. 1 One unique aspect of the current iteration of conversations around endemic police violence in the United States is unprecedented attention to the experiences of Black women, girls, and trans and gender nonconforming people targeted for police violence. Yet, what may appear to be a spontaneous increase in awareness of women, trans, and gender nonconforming people’s experiences of policing, or the result of a singular intervention, such as the Say Her Name report and campaign, 2 is in fact the product of decades of documentation, advocacy, and organizing by many, including a number of contributors to this issue. 3

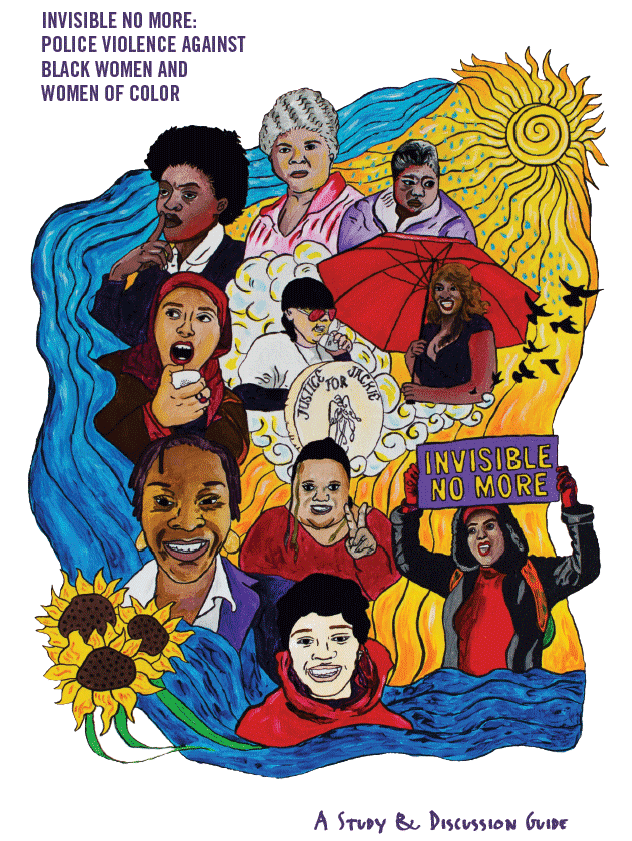

This issue of Scholar and Feminist Online takes up the current thread of discourse around policing, criminalization, mass incarceration, deportation, and detention 4 through the lens of Invisible No More: Resisting Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color in Troubled Times, a two-day conference hosted by the Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW) in November 2017. This was the second of three regional conferences held in Chicago, New York, and Berkeley, California, that explored and built on the themes and resistance strategies outlined in Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017) by one of the coeditors of this issue, BCRW Researcher-in-Residence Andrea J. Ritchie. 5

In Invisible No More, Ritchie chronicles over 400 years of state and law enforcement violence against Black women, Indigenous women, and women of color, as well as their long history of organizing and resistance, culminating in the current moment of heightened visibility. She places individual women’s stories that have risen to the surface of current discourses around policing in the United States – Sandra Bland, Rekia Boyd, Dajerria Becton, the #AssaultatSpringValleyHigh – into a broader context of historical and ongoing forms, sites, mechanisms, and structural drivers of police violence against Black women and women of color. She identifies commonalities and distinctions between the experiences of Black women, Indigenous women, and other women of color, as well as those of Black men and men of color. Taking a thoroughly intersectional approach, she explores the ways in which women, girls, and trans and gender-nonconforming people’s experiences of policing are informed by race, religion, national origin, relationship to the settler-colonial state, immigration status, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, class, disability, pregnancy, and parenthood – as well as by our society’s reliance on the police as our primary response to gender-based violence in our homes and communities. Her exploration of resistance movements that challenge state- and gender-based violence highlights how Black women and women of color often navigate dual positions as subjects of police and gender-based violence and as the backbone of movements that all too often erase their experiences.

During the Invisible No More conference, over thirty-five speakers and four hundred participants brought many of the conversations reflected in Invisible No More‘s pages to life and into the current political context of intensified immigration enforcement; reinvestment in draconian and discredited drug war tactics; 6 expansion of “broken windows” policing; 7 rampant Islamophobia; and attacks on gender, sexual, and reproductive autonomy, all of which fuel ever-greater policing of Black women, trans and gender nonconforming people, and women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color on every front. Community organizers, policy advocates, and scholars whose work informs Invisible No More delved into dialogue around policing at the intersections of gender, race, and sexuality within this increasingly tangled web of violent systems, and explored the ways in which women, trans, and gender nonconforming people of color’s experiences of policing – often still largely invisible in broader debates around criminal punishment – must fuel our resistance and drive us to envision new approaches to safety and accountability for harm. The contributors to this issue of Scholar and Feminist Online further explore the intricate ways Black women and women of color are ensnared within and navigate state projects of violence, as well as the functions that racially gendered policing and criminalization serve in advancing larger systems and relations of power.

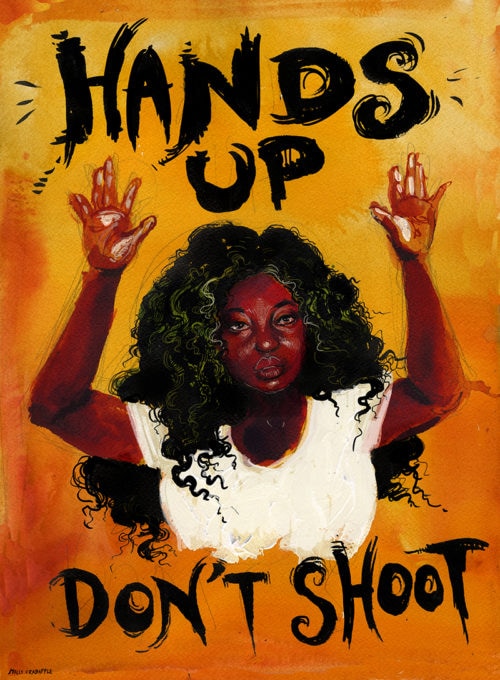

The violent regulation of Black women’s mere presence and protest in public spaces remains central to these projects. 8 Black women are the group most likely to be killed by police when unarmed, including Black men, and are killed a rate almost three times greater than white women. 9 Black women are also 17 per cent more likely to experience a traffic stop than white women. 10 Women of all races, disproportionately Black women and women of color, make up an increasingly large share of arrests annually, and the number of women nationwide who experienced use of force during police interactions quadrupled between 1999 and 2015. 11

Beyond these harsh realities, the contributors to this issue highlight the fact that police killings and public police violence are not always at the fulcrum of state violence where women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color are concerned. Policing extends to, and works in and through, various modalities such as the child welfare system, the medical industrial complex, 12 and the distribution of protection and punishment. In this way, sites such as the doctor’s examination room, the case manager’s office, and the sex offender registry are spaces in which policing and state violence is present for women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color, but invisible to the broader public. Both Invisible No More and the contributors to this issue explore private spaces gendered “female,” such as homes and hospital delivery rooms, as sites where, away from the public gaze or cop-watching cameras, the bodies and actions of Black women and women of color are subject to surveillance, scrutiny, policing, and punishment. These interactions, as well as experiences of police violence or neglect in the context of responses to violence or calls for assistance, blur the spatial and theoretical lines that separate public/private and state/interpersonal violence, and force open the parameters of academic and public discourses of policing, criminalization, and gender-based violence – and resistance.

Beyond exposing these gendered spaces of policing, the contributors to this volume also explore the racially gendered frameworks and implications that shape systemic state violence against women, and the ways in which gender is mobilized in the policing of Black women, trans and gender nonconforming people and women, trans and gender nonconforming people of color in service of reinforcing white supremacy, Islamophobia, class and geopolitical imperatives, and gender and sexual boundaries. For instance, the violence that Black women experience is embedded in what Black feminist theorist Hortense Spillers refers to as “ungendering”: the sociohistorical practice by which Black women are rendered commodities, thereby making them illegible as gendered beings. 13 Ungendering delineates the ways in which Black bodies have been unmarked by and through dehumanizing Western gender binaries as a way to validate and maintain the dominant position and humanity of white gendered subjects. Spillers highlights how Black women have historically been ideologically severed from will and desire, discursively transformed into “flesh,” and imbued with use-value that erases their humanity. 14 Simultaneously, their physical, sexual, and spiritual torture is justified and normalized through the development and dissemination of what Patricia Hill Collins calls “controlling narratives,” which shape perceptions of Black women and inform both private discourse and public policy. 15 These historical processes, originating in the Middle Passage and maintenance of the institution of chattel slavery, shape and haunt the present by culturally marking Black women as definitionally excluded from the normative categories of “mother,” “victim,” or “patient”; as inherently embodying predation and sexual deviance; and as devoid of any entitlement to privacy, bodily integrity, or maintenance of family relations.

As Ritchie posits in Invisible No More, and as the contributors to this issue remind us, this process shapes Black women, trans, and gender nonconforming people’s interactions with police officers, child welfare authorities, and medical professionals; institutional enforcement of prostitution and trafficking laws; and police responses to interpersonal and community violence. As Sharon Cooper, Sandra Bland’s sister, put it in a May 2019 opinion piece following the release, nearly four years after her death, of Bland’s own cellphone video of her fateful traffic stop: “My sister died because a police officer saw her as a threatening black woman rather than human … Our mere existence is perceived as such a threat to police officers that we’re consistently asked to pay for our freedom with our bodies and sometimes even with our blood.” 16 Simone John’s chilling recitation of the questions that Bland repeats during the “Driving while Black” traffic stop in her poem “Unanswered Questions,” as well as her visceral exploration of how so many Black women see and feel themselves in Bland’s ultimately fatal interaction with the officer in “On [Not] Watching the Video,” poignantly underscores this point. 17

Ungendering also contributes to the ongoing structuring of conversations around racial, police, and gender-based violence such that Black women’s experiences of enforcement violence in these contexts are not legible as violence. 18 John articulates the violence enacted through the invisibility of violations of Black women’s bodies in plain sight in “Elegy for Dead Black Women #1 ,” 19 which opens the present issue. Invisible, too, are decades and centuries of resistance to state-sponsored violations of Black women’s bodies. Current narratives thus not only lack the grammar to perceive Black women as the recipients of systemic harm, but also to understand Black women’s resistance.

Expanding the frame of our analysis of policing to broader communities of women of color, in “Waging the War on Terror against Muslim Women,” Chaumtoli Huq articulates the operation of gendered logics of white Christian supremacy in the United States’s “war on terror,” in which Muslim women are simultaneously gendered as subjects in need of protection and liberation from Islam to justify imperialist wars, and as incipient threats whose adherence to their faith ungenders them into the category of “terrorist.” Mizue Aizeki explores resistance to increased collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration authorities in New York City in an article that is squarely situated in the reality that immigrant women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color are gendered outside the category of “victim” through ideologies that pose migrants as social, economic, and cultural threats, manifest through practices of criminalization. And Lee Ann Adkins, in her first-person narrative of being required to register as a sex offender following a trafficking conviction, illuminates how white women can also be expelled from the category of victim through participation in sexualities deemed deviant, and by engaging in mutual aid in criminalized economies, to the point of being categorized as perpetrators of violence. While Black women, women of color, and white women occupy distinct and specific locations in relation to police violence and policing, these contributors point toward continuities in the reification of racialized gender categories in individual acts and systems of policing that represent fertile sites of both theorization and potential collaborative resistance, rooted in an understanding of the operation of gender as central tool of state power, white Christian supremacy, imperialism, and heteropatriarchy.

Police interactions are not only sites of ungendering of Black women and women of color, but also of explicit enforcement of the gender binary. 20 In a video clip of his remarks, conference speaker Gabriel Arkles, a Muslim trans man formerly of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project and now an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) LGBT and HIV project, describes historical and current processes of explicit gendering by police in day-to-day interactions. Enforcement of now-defunct laws that prohibited cross-dressing was just one of many justifications offered for the infamous raid of the Stonewall Inn fifty years ago this year, and served as a primary method of criminalization of queer and gender nonconforming bodies beginning in the seventeenth century through the late 1980s. Arkles cites the continuing operation of gender policing in the absence of laws explicitly authorizing it, and notes the continuing regulation of clothing and appearance through enforcement of school dress codes leading Black girls to be disciplined and pushed out of school for wearing their hair in an Afro or braids, Native boys to be targeted for wearing long hair, and trans youth to be policed in school hallways and bathrooms based on gender nonconforming appearance or behaviors. Extending beyond schools to the street, Arkles emphasizes that policing inherently involves assumptions of criminality rooted in enforcement of the gender binary – citing to a case in which a trans woman carrying a purse was profiled by police as a purse snatcher, the ways in which women of color – trans and cis – who are perceived to be wearing “feminine” clothing are presumed to be involved in prostitution, and Muslim women’s head coverings render them targets of surveillance and suspicion, and to a discussion in Invisible No More of how women perceived to be wearing “masculine” clothing are profiled as involved in gangs or violent crime.

In another video clip from the conference that appears in this issue, Arkles’s copanelist LaLa Zanell, a Black trans woman and former lead organizer at the New York City Anti-violence Project, now also at the ACLU LGBT and HIV Project, emphasized the ways gender is enacted and enforced in each strand of the criminalizing webs explored throughout the conference, including when police enact violence against trans and gender nonconforming people, target trans women for extortion of sex, enforce prostitution laws, threaten to call immigration authorities, fail to respond to calls for assistance or take reports of violence, and assume that Black trans women are perpetrators rather than entitled to protection. Zanell draws attention to a particularly wrenching example of violence against trans women in drug law enforcement, citing the case of Shelley “Treasure” Hilliard, who was killed in Zanell’s hometown of Detroit after police forced her to serve as an informant against her dealer and then cavalierly disclosed her role in his arrest. 21 Noting that violent gender policing is not limited to law enforcement, Zanell points to the structural exclusion of trans and gender nonconforming people from formal economies and services, driving them into the heart of criminalizing webs and the violent gender policing therein. She concludes with a call to action to cisgender women to combat gender policing in all its forms: “We need people like all these beautiful women in here to show up for us like we show up for you.”

Conference conversations and contributors also urge us to extend our gaze beyond visibility in conversations about police violence, and to ask ourselves how, in concrete and practical terms, these realities must shape our resistance. In a video clip from the opening conference panel, “From Combahee to Stonewall to #SayHerName,” BCRW Researcher-in-Residence Mariame Kaba expounds:

What happens when you define policing as actually an entire system of harassment violence and surveillance that keeps oppressive gender and racial hierarchies in place? … It forces you to focus on its systemic structural issues that need to be addressed … police violence is a misnomer, it’s actually redundant, because policing is violence in and of itself … And when you start talking about policing as if it is a system that is about harassment violence, and surveillance, then you are not going to accept bullshit reform. You’re going to understand from the beginning that what we are talking about is the horizon of abolition. That is the only way.

Dean Spade, Barnard alum, Sylvia Rivera Law Project founder, and author of Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law (Duke Press, 2015), reflects on a decade of organizing efforts to change policies and practices with respect to police interactions with trans and gender nonconforming people, and similarly concludes that it has not unseated the racially gendered logics and operations of policing, pointing us instead to focus instead on reducing the role of police in our lives. Spade points us to examples of communities working to do just that, such as Oakland Power Projects, which works to build community capacity to respond to mental health crises without police involvement, 22 Seattle’s Block the Bunker campaign to stop construction of a $160 million police facility, 23 and the Deadly Exchange program at Jewish Voice for Peace, which seeks to desilo decolonial solidarity initiatives from domestic struggles to end police violence and militarization. 24

The work of these groups – as well as that of Project Nia, founded by Kaba, and the Safe Outside the System Collective, founded and described by contributor Ejeris Dixon in “What Alex Taught Me” – and of many others described in Invisible No More, does not stop at making the statement that state violence is happening to women, trans, and gender nonconforming people of color. Community organizers have confronted that reality by building tangible and spiritual infrastructure to enable us to address, heal from, and prevent interpersonal and systemic harm – not only by strengthening community bonds, but by developing an entirely different grammar of harm and justice, evidenced by the resources gathered together by Kaba at TransformHarm.org. The struggle for visibility must have as its ultimate goal not only the illumination of the intersections of structures and manifestations of power in the lives of Black women, trans and gender nonconforming people and women, trans and gender nonconforming people of color, but also the creation and construction of common ground, solidarity, and resistance to racialized state gender violence at this nexus, exploring the meaning of visibility as praxis.

Contributors to this issue of Scholar and Feminist Online offer reflections on these questions in multiple forms, ranging from poetry to visual art to scholarly essays to biographical explorations, often with several intertwining in a single piece. Each contribution to this issue is intensely personal and sends out a call to each of us as individuals and collectives to respond not only by engaging intellectually, but also by examining our own role, complicity, and commitment to going beyond simply increasing the visibility of Black women, girls and trans and gender nonconforming people’s experiences of policing, to taking action within ourselves and our communities to begin to unravel the criminalizing webs and controlling narratives that fuel them. Frequently in academic writing it is difficult for the reader to locate themselves in the structural analysis that scholarly pieces offer. The message of a piece may suggest that power extends beyond prison walls, but there is seldom a call for the reader to reflect on the interpersonal element of the issue or the interpersonal dynamic of the system. Pieces such as Alexis Yeboah-Kodie’s “For the Love of Black Healing, Call in Black Men and Boys” reach out directly to readers to collectively and personally intervene on our roles in reproduction of harm. As Angela Y. Davis emphasizes in a 2016 conversation with Barnard Center for Research on Women activist-in-residence CeCe McDonald: “We often replicate the structures of oppression and violence in our own emotions … We often do the work of the state through our own emotions without even realizing it.” 25 This replication of oppressive structures can take the form of promoting of controlling narratives informed by ungendering, victim blaming, colorism, exile, patriarchy, transphobia, and homophobia within our communities.

Biographical or first-hand accounts are often understood as primary sources upon which academic analysis is made, rather than as critiques in and of themselves. The contributors to this issue gesture toward a very different epistemological framework of knowledge production and grounds for organizing. By centering first-hand accounts and positioning them as guiding analytical forces, they challenge what constitutes scholarship, as well as the limitations of predominant frameworks in educational institutions regarding working toward social change. This multigenre issue offers the reader a glimpse of active, real-time knowledge production through dialogue between poets, healers, lawyers, survivors, and scholars.

An Overview of this Issue

In part 1, contributors situate and elaborate upon the experiences of Black women and trans and gender nonconforming people and women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color within current discourses of policing and state violence through several strands of criminalizing webs, at the hands of actors ranging from beat cops to FBI agents to immigration enforcers to probation officers. Simultaneously, they introduce broader notions of policing and criminalization beyond law enforcement agents to include social workers, nurses, doctors, and other “helping professionals.” Each of the contributors place the growth of policing within the context of neoliberal policies underpinning racial capitalism, gutting social services, advancing militarization, and global imperialism – all positing these forces as inseparable from policing and criminalization.

In a video clip of her remarks at the conference, Communities United for Police Reform director Joo-Hyun Kang, whose theorization and activism first explored gendered manifestations of broken windows policing in New York City in the 1990s, emphasizes the continuing danger posed by the paradigm’s prevalence across the country and around the world: “Broken windows … creates groups of people considered undesirable and disorderly just by nature of who we are … Broken windows really sets up how communities as a whole get criminalized … by simply type-casting them as disorderly. We’re not actually talking about threats to our safety, we’re talking about whether people who have systemic power feel like their order is threatened. And that’s actually very dangerous if we buy into it.”

Kassandra Frederique of the Drug Policy Alliance elaborates on the gendered origins of the war on drugs in a clip of her conference remarks:

We also have to talk about how white women were used as a vehicle for why to make drugs illegal. Because people were scared that Chinese men would use opium and try to rape white women, just like they thought that people using marijuana would have Mexicans rape white women, which made people think that if Black men had cocaine they would rape white women … so when we start a conversation about women and drugs, and women being a footnote, it’s understanding that gender and women have always been part of the propaganda that has laid the conversation around how we create that we criminalize drugs in the first place.

She goes on to highlight how women’s drug use is framed as a response to trauma at best, and inherently disregulated at worst, to be punished regardless, even as men’s right to recreational drug use is increasingly normalized. To conclude, she describes one of the many ways that racial disparities in the drug war play out on women’s bodies:

When women or parents are talking to social workers about having a hard time with rearing their children … even the mere mention of marijuana being a part of their routine can cause a child neglect case to be formed … because they were honest with their social worker who acts as their police officer in those cases …When we talk about the war on drugs we are even talking about the hospital social workers that when someone gives birth to their child where people are illegally tested for drugs and … a social worker comes into your hospital room and tells you can’t take your kid home. But we’re not talking about white women – the white women we were supposed to protect, which is why we made all the drugs illegal in the first place, because those women are not in hospitals that get tested. But when you look at the research that shows that if you are going to test at the same rate, it’s more likely that white women will test positive for drugs, we’re not talking about them because we are going to consistently criminalize women of color for their possession, use, or sale of drugs.

In so doing, Frederique sets the stage for Dinah Ortiz’s powerful and haunting contribution, “Fighting an Unjust Battle: How the War on Drugs Stole My Daughter,” in which she offers an unsparing look at the lifetime consequences imposed on women who use drugs and attempt to reduce harms the best way they can in the absence of social supports, awash in a sea of judgment and punitive responses designed to separate Black mothers from their children.

In “Mass Deportation and Criminalization under the Homeland Security State: Anti-violence Advocates Fight against Domestic, Intimate Partner, and State Violence,” long-time immigrant rights advocate and acting director of New York City’s Immigrant Defense project Mizue Aizeki picks up on themes explored in Scholar and Feminist Online issue 6.3, “Borders and Belonging: Gender and Immigration,” extends the chronology of US anti-immigrant policy into the present and includes its impacts on criminalized survivors of domestic and community violence. She goes on to chronicle New York City-based resistance to the growing conflation of immigration enforcement machinery with the carceral apparatus of policing and punishment under the Obama administration that was not rooted in exceptionalizing survivors of violence as “deserving” innocents while reinforcing criminalizing narratives of immigrant “others” who must be detected and neutralized through incarceration and deportation. Rather, this resistance was anchored in acknowledgement that victimization and criminalization are often inextricably intertwined in the lives of women and queer people of color, making surgical carve outs to punitive immigration laws impossible, and necessitating resistance strategies on behalf and with survivors of violence that challenge carceral logics and policies of exclusion and deportation wholesale.

In an unusual pairing of client and attorney voices, LeeAnn Adkins, Kate Mogulescu, and K.B. White illuminate the ways in which policing of prostitution and trafficking ensnare those they claim to protect in criminalizing webs. They also highlight the ways in which policing extends beyond initial contact with the criminal legal system, following women long after their release from prison through policing by probation officers and sex offender registration requirements. As highlighted in Invisible No More’s discussion of Women with a Vision’s No Justice campaign to eliminate sex offender registration requirements for people convicted of “crime against nature by solicitation” in Louisiana, 26 measures designed to protect imagined white women and girls from sexual predators are used to criminalize Black women, trans, and gender nonconforming people deemed inherently sexually deviant and predatory through controlling narratives rooted in slavery, sometimes simultaneously ensnaring white women who deviate from normative sexualities.

In part 2, contributors invite us to examine the role law enforcement explicitly plays in regulating and enforcing the lines of racialized gender through the experiences of trans and gender nonconforming people described by Arkles and Zanell. They go on to draw attention to private spaces of gendered policing in the context of health care provision, policing pregnancy, and child welfare enforcement. In her opening remarks for the “Policing Motherhood” panel at the conference, Dorothy Roberts, author of Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty and Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare, who has led the way in making connections between criminalization and child welfare enforcement in the lives of Black women, illuminates the parallel and often-intersecting operation of the carceral and welfare state, and concludes with a clarion call for abolition of the child welfare system rooted in this analysis. In “Mutually Reinforcing and Intersecting Systems,” journalist and author Victoria Law further explores the intersection between the two systems with statistics and two heartbreaking stories gathered through her decade of coverage at the intersection of gender and mass incarceration. “Do No Harm” by National Advocates for Pregnant Women board member Jeanne Flavin and founding executive director Lynn Paltrow highlights the role of medical professionals in criminalization of pregnant and parenting people, urging them to heed the call of their oath to place their patients’ wellbeing over the demands of the carceral state. The long legacy of medical invasion of, experimentation on, and violation of Black women’s bodies is laid bare in the choreopoem “Psalm for the Mismeasured and Unfit,” by former BCRW activist-in-residence Cara Page, living into the legacy of the late Barnard alumna Ntozake Shange. Former family defense attorney and cofounder of the Movement for Family Power Erin Miles Cloud closes out part 2 by picking up Roberts’s call for abolition of the child welfare system and bolstering it with narratives of individual and collective profit made off of the bodies of Black children in foster care. Cloud emphasizes that the same narratives of “bad Black mothers” that drove child separation during slavery continue to drive the removal of children by the child welfare system, the punishment of Black mothers through war on drugs that Ortiz describes, and the ongoing blame of Black women for the harms and conditions society creates in which they, and their children, seek to survive.

In part 3, the contributors invite us to contemplate the question: if not police, then what? How must our everyday conversations, celebrations, and community creations lead us on a path toward transformative approaches to safety, healing, and what the “INCITE! Critical Resistance Statement on Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex” calls “a society based on radical freedom, mutual accountability, and passionate reciprocity. In this society, safety and security will not be premised on violence or the threat of violence; [they] will be based on a collective commitment to guaranteeing the survival and care of all peoples.” 27 Beyond the resources that these contributors, as well as Kaba at TransformHarm.org, describe, a number of seminal and recent publications chronicle the efforts of women and trans and gender nonconforming people to build toward such a society, including INCITE!’s The Color of Violence anthology (South End Press, 2006; republished by Duke University Press, 2015); Alisa Bierria, Mimi Kim, and Clarissa Rojas’s 2012 special issue of Social Justice: A Journal of Crime, Conflict & World Order,, “Community Accountability: Emerging Movements to Transform Violence” (Vol 37, No. 4, 2011-2012); Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence within Activist Communities (AK Press, 2016); Ann Russo’s Feminist Accountability: Disrupting Violence and Transforming Power (NYU Press, 2018); Emily Thuma’s All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence (University of Illinois Press, 2019); Mariame Kaba and Shira Hassan’s Fumbling toward Repair (Just Practice and Project Nia 2019, available from AK Press); Aisha Shahidah Simmons’s Love with Accountability: Digging up the Roots of Child Sexual Abuse (AK Press, 2019); and Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movements, edited by contributor Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (forthcoming, AK Press).

Last, but certainly not least, Meryleen Mena in “No End in Sight?” and Robyn Maynard in “Transnational Affinities” do the critical work in part 4 of extending our gaze and resistance beyond the national boundaries of the United States and Canada to a more global understanding of the manifestations and connections between racially gendered state violence against Black women’s bodies – and the powerful possibilities such an expanded vision offers to our global resistance.

The title of the conference, and book that serve as its points of departure, is a statement of fact, an aspiration, and a demand. Together they offer a continued call not only to visibility, but also to each of us to ask ourselves what it truly means to #SayHerName – and how each of us can take steps toward creating a future in which not only will the violence of policing experienced by Black women and trans and gender nonconforming people and women and trans and gender nonconforming people of color, in all its forms, in public and private, no longer exist, but in which each of us will remain vigilant about our role in reproducing it and our responsibility for our collective safety and liberation.

- See the Movement for Black Lives, www.mvmt4BlackLives.org; Barbara Ransby, Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018); Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2016).[↑]

- Kimberle Williams Crenshaw and Andrea J. Ritchie, Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality against Black Women (African American Policy Forum, 2015), and see http://aapf.org/shn-campaign.[↑]

- See Andrea J. Ritchie, Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017). Generally speaking, policing of Indigenous women and non-Black women of color has garnered less attention historically and in the current moment in the United States.[↑]

- This is not the first time Scholar and Feminist Online has tackled issues of race, gender, and criminalization. See, e.g., issue 6.3 and issue 5.3.[↑]

- Ritchie, Invisible No More. Ritchie is also the coauthor with Kimberle Williams Crenshaw of Say Her Name, and the coauthor with Joey L. Mogul and Kay Whitlock of Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Beacon Press, 2011).[↑]

- See Richard Saenz, Kara Inglehart, and Andrea J. Ritchie, The Impact of the Trump Administration’s Federal Criminal Justice Initiatives on LGBTQ People and Communities and Opportunities for Local Resistance National LGBTQ and HIV Criminal Justice Working Group and Lambda Legal, 2017, https://www.lambdalegal.org/sites/default/files/publications/downloads/the_impact_of_the_trump_administrations_federal_criminal_justice_initiatives_on_lgbtq_people_communities_and_opportunities_for_local_resistance.pdf.[↑]

- For more information on broken windows policing, see Ritchie, Invisible No More; Andrea J. Ritchie, “Black Lives over Broken Windows,” Public Eye, Spring 2016, https://www.politicalresearch.org/2016/07/06/black-lives-over-broken-windows-challenging-the-policing-paradigm-rooted-in-right-wing-folk-wisdom/.[↑]

- Jenn Jackson, “#SayHerName – Police Violence against Black Women and Girls: An Interview with Andrea J. Ritchie,” Black Perspectives, 11 June 2018, https://www.aaihs.org/sayhername-police-violence-against-black-women-and-girls-an-interview-with-andrea-ritchie/[↑]

- Odis Johnson, et al., “Race, Gender, and the Contexts of Unarmed Fatal

Interactions with Police,” https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/sites.wustl.edu/dist/b/1205/files/2018/02/Race-Gender-and-Unarmed-1y9md6e.pdf.

[↑] - Johnson, “Race, Gender.”[↑]

- Prison Policy Initiative, Policing Women: Race and Gender Disparities in Police Stops, Searches, and Use of Force, 14 May 2019.[↑]

- Disability justice activists Mia Mingus, Cara Page, and Patty Berne describe the medical industrial complex, as “an enormous system with tentacles that reach beyond simply doctors, nurses, clinics, and hospitals. It is a system about profit, first and foremost, rather than ‘health,’ wellbeing and care. Its roots run deep and its history and present are connected to everything including eugenics, capitalism, colonization, slavery, immigration, war, prisons, and reproductive oppression. It is not just a major piece of the history of ableism, but all systems of oppression.” Medical Industrial Complex Visual, February 2015, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2015/02/06/medical-industrial-complex-visual/.[↑]

- Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, 2 (1987): 65.[↑]

- Ibid., 67.[↑]

- Ritchie, Invisible No More, 35–42.[↑]

- Sharon Cooper, “Sandra Bland’s Sister: She Died Because Officer Saw Her as ‘Threatening Black Woman,’ Not Human,” USA Today, 13 May 2019.[↑]

- Simone John, Testify (Portland: Octopus Books, 2017): 57, 67, and reprinted in this issue.[↑]

- Spillers, “Mama’s Baby,” 65, 67.[↑]

- John, Testify, 54.[↑]

- Ritchie, Invisible No More, 127–44.[↑]

- For more on Shelley “Treasure” Hilliard, see dream hampton, Treasure: From Tragedy to Trans Justice, Mapping a Detroit Story, https://www.amazon.com/Treasure-Tragedy-Justice-Mapping-Detroit/dp/B073WJRZNK/; Ritchie, Invisible No More, 52.[↑]

- For more information on Oakland Power Projects, see https://oaklandpowerprojects.org/.[↑]

- For more information on Block the Bunker, see https://blockthebunker.org/.[↑]

- For more information on Deadly Exchanges, see https://deadlyexchange.org/.[↑]

- Free Cece!, directed by Jacqueline Gares (2016; US).[↑]

- Ritchie, Invisible No More, 161–4.[↑]

- Critical Resistance and INCITE! Women of Color against Violence, “INCITE! Critical Resistance Statement on Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex,” in Color of Violence: The INCITE! Anthology (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015 [2006]): 226.[↑]