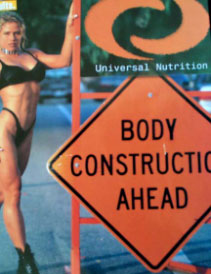

There are many ways, however, that sport is complicit with the values associated with neoliberalism and its attendant immersion in tech time. The effort to live in tech time represents not just acceleration but also the effort to overcome biological time through body practices and technologies such as plastic surgery, gene replacement therapy, and performance enhancing steroids. Such practices are hallmarks of globalization, which offers the free market as the source of all possibilities, including transcending the “limitations” of biology. Much advertisement in the fitness industries directly makes this claim:

It is highly significant that during the eighties, at least in the “developed” Western world, sport and the related fitness industries were complicit with, in Samantha King’s words, “the emergence of the fit body as a primary emblem of neoconservative ideologies of the period.” 1 Much work in cultural studies has been done to establish links between the built-body aesthetic of movie icons such as Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, the deregulation and increasing corporatization of the public sphere and, for instance, Reagan’s infamous “Star Wars” program. 2 In terms of locating bodily aesthetics and practice, scholars such as Susan Bordo have written extensively on how the supposed plasticity of the postmodern body within this larger economic structure is linked to a dream of transcending the body’s limitations. 3

Given the lesser status historically granted to us because of our supposedly weaker bodies, the discourse of athletics as the transcendence of limitations was particularly compelling to us female athletes in the early 1980s. To prove that we were “not just girls,” and therefore subject to weakness, incompetence, and emotionality, we had to train harder and be even more focused and single-minded than our male counterparts – we had to be better neoliberal subjects, so to speak. Our fit bodies and athletic performances were the outward expressions of our abilities to transcend biology and gender limitations, and the fact that many of us had eating disorders was not unrelated to this. As white women striving for success in a public sphere newly supposed in the West to be egalitarian, our athletic careers allowed us to dispense, temporarily, with our historical connections to immanence and caretaking. As Mellor writes,

to take their place in the modern Western public world, women must present themselves either as autonomous individuals, “honorary men” who are expected to work in the public sphere while avoiding domestic obligations undertaking them in the “free” time, or by paying someone else (often another woman or “domestic servant”) to carry out that work. In societies that aim to transcend biological and ecological time, it would never be possible for all to participate freely and equally, as patterns of unsustainable transcendence on the part of dominant groups will be mirrored by patterns of subordination and exploitation for those who have to carry the burden of unsustainability. 4

The cultural anxiety about female athletes retaining their femininity is not, I think, unrelated to the kinds of materialities that Mellor describes here. Retaining femininity means precisely retaining those linkages to the biological body and biological time – as Mellor notes, “someone has got to live in biological time.” Anxiety about women breaking that link – who will do the basic work of caretaking then? – is directly related to the omnipresence of discourses such as “she’s an athlete, but still feminine” (which certainly informed the heightened femininity of the women pictured in my team photo – I was actually wearing a red and blue bow – Arizona’s colors – in my hair).

While many scholars have documented the relationship between homophobia and the emphasis on femininity (femininity defined, I would argue, as the willingness to signify immanence), what has been less discussed are the ways “retaining femininity” is also connected to retaining one’s biological role of immanence, of living in biological time and caring for the bodies of others. 5 Of course the two issues are related: dominant homophobic discourses see female athletes as “mannish,” and it is this “mannishness” which threatens to break the presumed link between the biological female body and social practices of caretaking. But the cultural assumptions behind terms like “femininity” and “masculinity” are directly informed by the linkages Mellor outlines, so that “femininity” equals immanence and a predisposition to care for others, while “masculinity” equals transcendence and a predisposition to “get one’s own.” This is racially inflected to the extent that historically whiteness has been associated with transcendence, and every other racial category with immanence, so that it is easier for white female athletes than for their non-white counterparts to be associated with transcendence, although there is still pressure to reconfigure even white female athletes in terms of immanence.

- David Andrews et al., Qualitative Methods, 26.[↑]

- See especially Yvonne Tasker, Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre, and the Action Cinema (N.Y.: Routledge, 1993) and Susan Jeffords, Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1994).[↑]

- See Susan Bordo, “Material Girl: The Effacements of Postmodern Culture,” Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, 10th anniv. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 245-275.[↑]

- Mellor, “Ecofeminism,” 215.[↑]

- On linkages between women’s sports and homophobia, see Pat Griffin, Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998) and Mary Jo Festle, Playing Nice: Politics and Apologies in Women’s Sports (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).[↑]