Chris Cynn: How did you read that imagery of the rainbow in for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf? The women are costumed in different colors. You said you didn’t want them to be stereotyped into characteristics or types. But then, the color imagery is so vivid. How did you read the colors?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: A rainbow is one thing. But it’s made of many different things, and the one is just as beautiful as the singular parts of it, and so, as women, we are all different, but we are all one.

Chris Cynn: Is [your writing] influenced by Shange’s work either directly or indirectly? Or are other Kenyan writers, playwrights who you might know who are influenced by her and her work?

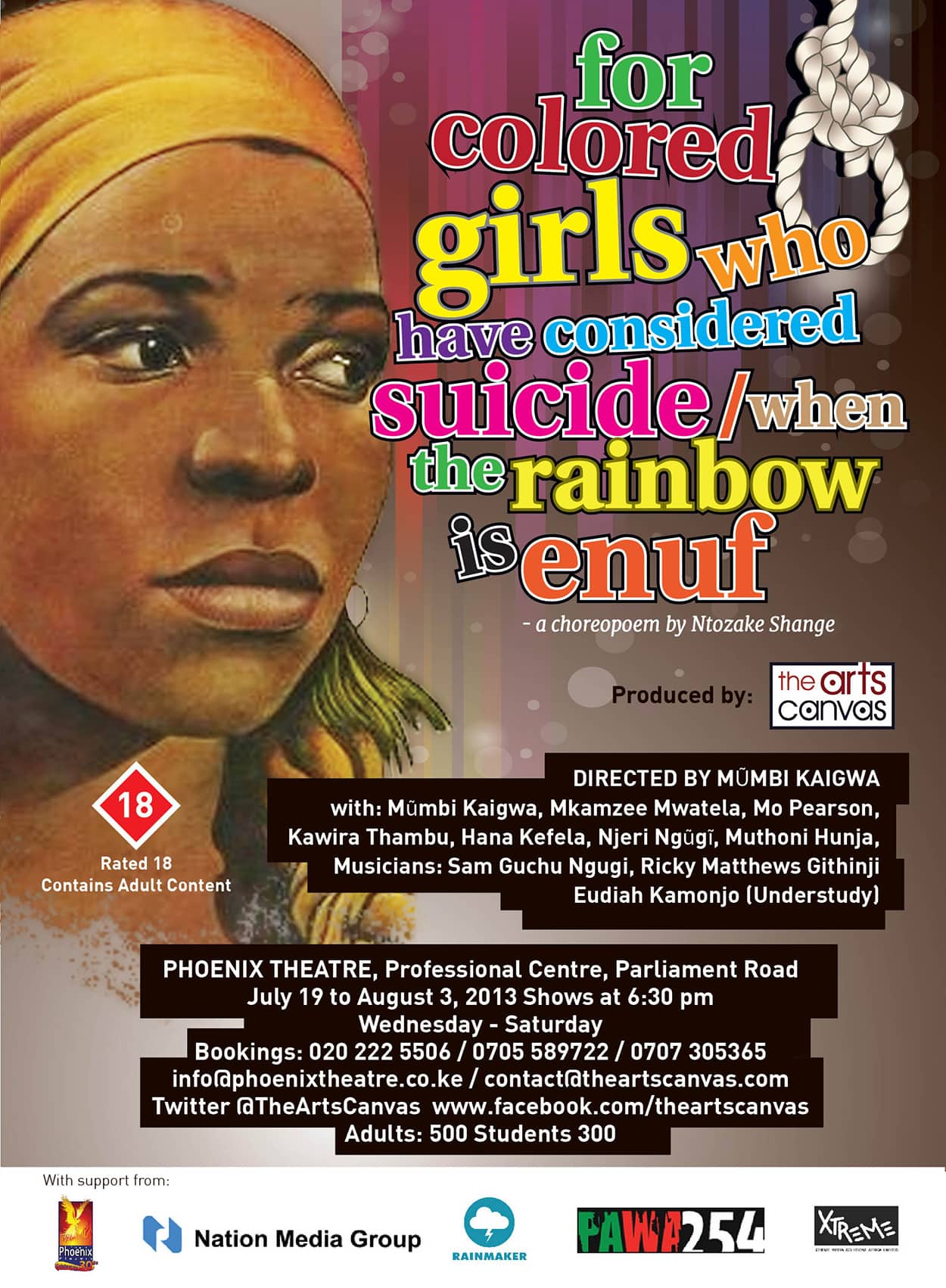

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I think that my work has been influenced by everything that I’ve done. If it is a trilogy, then the first play is called Voice of the Dream. I used to work for the United Nations, and I had always been an actress since I was ten, so I didn’t know that it was a job that I could do. When I came out of the United Nations, I sort of stumbled into becoming a performer and a producer and a director and an owner of a theater company, quite by chance … I was being interviewed on television one day—this is around 2001—and somebody asked how I did it because they wanted to know what the secret was for leaving a well paying job and following a dream.

And I said, “I have no idea.” So I kept being asked this question and a friend of mine, with whom I danced, I mentioned it to her and she said, “well, if you don’t know how it is that you did it, or how it is that it’s done, you should ask people.” So my first play was actually a piece of documentary theater, which I thought I’d invented.4 And so, if I would be anything, I would be trying to tell as personal stories as I can, so that they reach people directly in their hearts, and I think that is one of the things that I find Ms. Shange’s work does for me.

But it’s very, very moving. That story in the end, about the lady in brown and crystal, was shattering. We had people in tears every single night because that story is so personal.

Chris Cynn: Were you consciously trying to effect transformations in the audience as well?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: Always, always, absolutely always. It’s pretty much the only reason why I do what I do. I didn’t realize how powerful my work was until people would start coming up to me and saying—twelve years after I did Death and the Maiden—that their life changed on that night, and they’ve never been the same.5

The woman who I spoke about earlier, who said that she was about to kill herself, she saw the advert for the play on Facebook, and we spoke, as one does online. I still haven’t met her. So we communicated online, chatting for maybe six hours. And I said that she should come see the play before she did anything else and she came as my guest to watch the show. I didn’t manage to see her, but I knew she was there, and she wrote me to say that she had been transformed. So it’s a scary situation to be in, to be someone who has that kind of gift—that I appreciate that I must have been given it for a reason.

Chris Cynn: The play is so much about gender too, and relations between men and women. I’m wondering whether you were also hoping to change mindsets around gendering. The play is also about race, too, in the US context. I’m wondering what kinds of changes you were hoping to effect in the Kenyan context around gender, and possibly around race as well?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I’m not sure that I know. I know that I’m drawn to material that has strong social justice contexts, and so, I’ve done stuff on human rights, but also on drug abuse and human torture, and I’ve done a production of The Vagina Monologues almost every year for ten years. I did the first one.6

But I’m pretty much—I’m not sure that I could say to you what it is I intend because it comes out of the material, and unfortunately, I don’t write as much as I feel I could or should. But very often, it’s difficult to find material that will say the kinds of things that need saying, particularly right now. Politically in Kenya, we’re at a bit of a crossroads with our president and our vice president, our deputy president, before the ICC, the International Criminal Court, and so that’s generally affecting us in many, many, many different unknown and complicated ways as a nation.7 But I think that my interest is not so much gender, as it seems to be women, but just human relations and the human condition and the way that we relate to one another as men and women, as black and white, as tribes, as human beings.

Having said that, it’s tough to be a performer in this part of the world because people don’t come out to watch stuff, and you’re often preaching to the choir, and your audiences are small.

Like I said, the theater that I was performing in most recently—the theater that we were performing for colored girls in, for instance—only had 120 seats, and while we had sold out performances for that particular production, other productions don’t do so well. Our biggest auditorium in Nairobi has maybe 600 seats. We are never really reaching the masses because we also don’t run for very long. Phoenix Theatre has 11 nights, and they run the longest in Nairobi. Everybody else runs for four nights, or two. A play is even just one night. So you are often forced to try and find different audiences.

I love to tour the work. I performed, for instance, in three different venues. We did 11 shows, actually 12—we added an extra one because we were selling out at Phoenix and then we did one show each in two other parts of town. But we are not reaching that many people.

Chris Cynn: Even here in the US, the arts are feeling the pinch economically, and you had mentioned the national political scene there, the ongoing turmoil. I’m wondering what sort of future you see for the arts, for theater in particular, for the kind of political social justice work that you’re so invested in?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I’m not encouraged. I’m not encouraged at all. It’s unfortunate because there is a lot of space to do a lot. But you can’t pay the bills on tickets and there’s very little, in fact there’s absolutely no government support—we don’t have arts councils. The people who were supporting our work—everybody goes to the same small pool of international nongovernmental organizations, and in my mind it’s getting less and less possible to do this sort of work. I would love to be able to do a three-year project or even a two-year project where we’re writing and devising and creating and producing, and then be taking the show on the road, around East Africa. But I’m still sort of working pretty much in the same way that I started working twelve years ago when I left the U.N. In between, there was some light towards East Africa. I did a three-year project where I trained young actors to devise work. But it doesn’t build on itself necessarily.

There doesn’t seem to be that many people to whom I can pass the baton. I’m 51 and there aren’t that many. I may be wrong. I would love for somebody to show up and say, “No, no, no! Here I am, standing here! I want to do it!”

With the filmmakers and the musicians, I feel that there’s a lot more, you see a lot more development over the ten years. But with the theater, I feel as if we’re really faced with a losing battle because we don’t have music and theater studies within our schools. By the time you get to university, you’re pretty much wanting to get a proper job, a job that will pay the money. And so, there isn’t a groundswell of people whose shirttails you can grab onto and say: Hoist me up and show me how it’s done, how I can make a living. People come into theater out of school, very enthusiastic. But as soon as they start having families or more responsibilities, they drop out. I’m kind of the only fool who is still here, who went into the employment and then came out, and it’s still pretty much not the norm.

But it’s been great, and what I’ve tried to do is combine that with things that were issue-based, HIV or conflict resolution work for organizations such as the United Nations. That then paid the bills so that I can then do the more interesting, meaty, grassroots work that I want to do.

But like I said before, and like you know I’m sure as well, the funding isn’t always there. And when it is only for a little project, you’ve got to stretch it over two years, when it was really supposed to be for six months.

Chris Cynn: Do those NGOs and the grant organizations dictate what productions, or influence what productions you decide to put on?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: Yeah, they wouldn’t necessarily be interested in something like Ntozake Shange’s work. But they might be interested in the method that was used or the style of the work to create something that was more local. Also sometimes, they insist on you partnering with people who … I recently did a project that was in jeopardy of not happening because I was supposed to work with a particular institution within the government that just was so bureaucratic and so painfully slow at moving, that we needed to do the project before the elections, and in the end, we almost didn’t make it. We had eight months to get there and it was just like pulling teeth. So sometimes that kind of thing, where the organization that’s giving you the grant insists that you do it in a particular way, or they want your support but not for the kind of work that you’re interested in doing. Like I’m not necessarily interested in doing shows that teach people how to dig boreholes, but maybe there’s an organization that wants to do plays that teach people how to dig boreholes. So we don’t connect. [Laughter]

Chris Cynn: Is there anything else that you would want to add in relation to Shange, your own work, the theater more generally, that I haven’t asked you but that you would want to include?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: One of the things that I really enjoyed doing, some years ago—we had a group of people, we were 11 of us from East Africa, and we came to the US with performances of our own as well as techniques to teach. We went to Dartmouth in New Hampshire. We worked with some of the kids there, and that was one of the highlights of my life because they were just so bright-eyed and so enthusiastic and so interested in the work that we were sharing with them. We sang and we did workshops and whatever it is that we did, and then we had a few days where we then performed the pieces that we had come with.

I think the tour was also very interesting because we then went to New York and spent a week talking to different playwrights and different practitioners. We met many of the people who were writers in contemporary work, and heard about their process and how they put pieces together, whether as writers or as directors. Then, we went to CUNY and we performed there as well.8

I think those sorts of tours are very useful, not only for ourselves as East Africans or as individual performers. But also, it’s very, very useful for the people who see our work because it gives them a whole different perspective of what African theater is about. Also, it negates a lot of the damage that’s been done by the media about what Africa is. And also, out of that there was hope that there would be collaborative work that would come out of that, so that we could then come and work in either universities or with those people we met on works that could grow the work of the people who we were engaging with. I think that those exchanges are very useful.

Chris Cynn: You mentioned before that you had not altered the text of for colored girls at all, in your production. But I’m very interested in what you were saying about a specifically African theater.

And I’m wondering what about your production, just in closing, what do you think was specifically African or specifically Kenyan [about your] for colored girls? You mentioned the music and the dance. But if there were other aspects …

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I know that there were African American women who came and watched the show. It’s difficult for me to say how much of it was African, but if I recall, as far as they were concerned, it was not the show that they would have expected to see in an American context. But I can’t tell you what it was that we did in the show because it would mean [that we are] ourselves thinking that we’re being American and maybe we’re not at all.

Chris Cynn: Yes, it would be very difficult for an American director to define exactly what’s American about their production as well, so that was kind of an off-the-cuff question in response to your interesting comment about an African theater and what audiences on this side can learn.

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I know that in terms of the audience, from the night that the African Americans were in the audience, we all knew they were there because they answered back. [Laughter] It was very call-and-response, and they were very engaged, which is something that happens with our theater when it’s not in a theater, when it’s out on the street or when it’s in a more informal setting. But I think that the African Americans—and I’m generalizing broadly here—they know that they can take the space and break those boundaries that say that we have to sit quietly in the seats.

Kenyan audiences tend to be very English because they were the ones who introduced us to theater, and so we sit meekly and talk afterwards about how I really wanted to laugh, but I wasn’t sure, was it okay, is it okay to laugh out loud? That’s the kind of thing that we see clearly from a Kenyan audience, whereas the African American was just answering us back.

Chris Cynn: There’s also maybe something about for colored girls that invites that kind of response as well.

Mũmbi Kaigwa: Yeah. Yeah, we thought we would get a lot more of it. I think we had, out of the 14 shows that we did, we probably only had that response twice or three times.

Chris Cynn: What are some of your plans for the future?

Mũmbi Kaigwa: I have two more plays in my retrospective, the next one was going to be five plays from the Humana festival, which we’ve done before and went down very well. The next big one will be They Call Me Wanjinko.

Chris Cynn: Best of luck with the future projects. I so appreciate the chance to talk with you. Take care of yourself.

Mũmbi Kaigwa: You too.

Chris Cynn: Thank you.

- According to Carol Martin’s definition: “Contemporary documentary theatre represents a struggle to shape and remember the most transitory history—the complex ways in which men and women think about the events that shape the landscapes of their lives …. Those who make documentary theatre interrogate specific events, systems of belief, and political affiliations precisely through the creation of their own versions of events, beliefs, and politics …. [I]t is a form of theatre in which technology is a primary factor in the transmission of knowledge.” See Carol Martin, “Bodies of Evidence,” TDR 50. 3 (2006): 8.) I found out about Anna Deavere Smith after I had written it, and then researched her style and her method to sort of create a style. I think that what I found in Anna Deavere Smith’s work, and also in Ntozake Shange’s work, is that the more personal—I’m sure I’m not the first one to have discovered this—the more personal the story is, the more universal. ((Anna Deveare Smith’s best-known documentary-theater-style work includes Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights Brooklyn and Other Identities (which incorporated an interview with Shange) (1992, 1993) and Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 (1993, 1994). [↩]

- In November 2011, Kaigwa directed and starred in a Phoenix Theatre production of Death and the Maiden, a 1990 play by Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman. [↩]

- Kaigwa produced the first performance of The Vagina Monologues in Kenya in 2003 and in Uganda in 2005. Based on interviews with over 200 women, Eve Ensler’s one-woman play, The Vagina Monologues, first published in 1998, is now performed annually at “V-Days” worldwide to raise awareness about violence against women. The Vagina Monologues has provoked intense controversy. For a critique of “V-Days” and the global feminist politics it purports to propagate, see Srimati Basu, “V Is For Veil, V Is For Ventriloquism,” Frontiers: A Journal Of Women Studies 31.1 (2010): 31-62. For an account of a South African production that reimagines the play, see Roxanne Bain, “Vagina Dentata—A Kabarett: Re-imagining The Vagina Monologues,” South African Theatre Journal 26.1 (2012): 45-60. For feminist critiques of the play from US perspectives, see Christine M. Cooper, “Worrying About Vaginas: Feminism And Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues,” Signs: Journal Of Women In Culture & Society 32.3 (2007): 727-758 and Kim Q. Hall, “Queerness, Disability, And The Vagina Monologues,” Hypatia 20.1 (2005): 99-119. For discussions of “V-Day” as a campus phenomenon, see Durden and Cobrin in this issue. [↩]

- President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto face ICC charges of ethnic cleansing related to violence after the contested 2007 elections that left at least 1,200 dead. Joshua Sang, head of operations of KASS FM Radio, also faces charges of ethnic cleansing, and journalist Walter Osapiri Barasa faces charges of attempting to corrupt witnesses. See http://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/icc/press%20and%20media/press%20releases/Pages/pr958.aspx and http://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/icc/press%20and%20media/press%20releases/Pages/pr948.aspx. Echoing a number of other scholars, Marcel Rutten and Sam Owuor challenge media accounts that frame the post-election violence as ethnic conflict. See Marcel Rutten and Sam Owuor, “Weapons of Mass Destruction: Land, Ethnicity and the 2007 Elections In Kenya,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 27.3 (2009): 305-324. For an account of post-election violence targeting women, see http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Press/OHCHRKenyareport.pdf (PDF). [↩]

- For a journalistic account of the trip, see Randy Gener, “East Africa Remakes The World,” American Theatre 25.9 (2008): 28-89. [↩]