Transnational Publics and the Branding of Human Rights

The global spread of electronic and new digital technologies over the last two decades has transformed the ways in which social movements organize their relationship to publicity (see McLagan 2002). Human rights activists have been in the forefront of the creation of a new kind of media activism, one that not only makes sophisticated and innovative use of techniques of celebrity and publicity through a wide range of forms, including older analog media such as print, photography, and film, and new digital media such as the Internet, CD-ROMs, and handheld video cameras, but that also involves the creation of new organizational structures that provide a kind of scaffolding for the production and distribution of these media. Indeed, a whole new arena of social practice has emerged around human rights media, from organizations that provide media training to activists such as WITNESS, and Digital Freedom Network, to those that provide outlets for distribution such as the International Human Rights Watch Film Festival, and Mediarights.org. These organizations help activists channel their media to their intended audiences, whether in classrooms, on home video, in movie theaters, on the Web, or in governmental (e.g. U.S. Congress), intergovernmental (the United Nations), and non-governmental forums. In providing the means for the production and distribution of human rights media, these new organizational forms are contributing to the creation of a new circulatory matrix or platform through which testimonies can summon witnessing publics.

This aspect of the human rights movement builds on a long history of pioneering work by Amnesty International, which was the first group to attempt to “brand” their organization through the creation of a logo in the 1970s. The explosion of rights-oriented digital media in the second half of the 1990s represents an expansion of this kind of image politics, with human rights activists self-consciously deploying complex rhetorical strategies borrowed from advertising.

Before the creation of the World Wide Web, political activists used the Internet to connect to each other via email, newsgroups, and chat rooms; the “virtual politics” (see McLagan 1996) carried out online was a largely logocentric affair. Since that time, as it has become faster, easier, and cheaper to send visual data electronically, there has been a seismic shift in political use of networked computers. Today activists of all stripes recognize the necessity of having a presence online – well-designed websites are now assumed to be key “portals” of entry into activism, especially by members of the younger generation who take the existence of the technology for granted. In the case of human rights websites, increasingly we find information and testimonies presented not in gritty realist documentary style, but embedded in such things as flash graphics and sometimes even supplemented by downloadable audio files in MP3 format – strategies which pivot not on emotional identification like that discussed above but rather on different forms of signification.

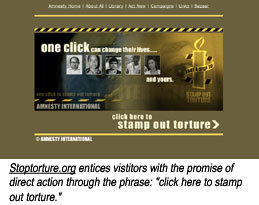

The significance of this shift in relation to age and generation was brought home to me in my teaching recently when I asked students in an undergraduate class on human rights to pick out their favorite rights websites. I was interested in what students thought about how the sites were organized and the aesthetic strategies that were used, as well as what conclusions they might draw about their potential efficacy as tools to promote human rights. One of sites we explored together was www.stoptorture.org, a project of Amnesty International. On the bottom of the screen were the words “click here to stamp out torture.” 1 Absurd as the proposition that one could simple click and stop such a practice might appear to me, none of my students appeared to question the claims of sites promising visitors this kind of “fast and easy activism.” The point was underscored when we looked at the site (www.mirrorimage.ai.org) of a local Amnesty International group based in the Boston/Cambridge area called Group 133 which was responsible for organizing a campaign to free 14 Tibetan nuns imprisoned by the Chinese for demanding their homeland’s independence. Group 133 launched www.drapchi14.org in December 2001. I had been interested in the site initially after reading something about the site’s innovative use of MP3 files. While in prison, the 14 young women managed to secretly make a tape recording of songs calling for Tibetan independence; the tape was smuggled out of Drapchi prison and eventually it landed on the desk of Robbie Barnett, founder of Tibet Information Network, in London. 2 After removing the names of the women on the tape in order to protect their identities, Barnett made the tape available to human rights groups interested in the nuns’ situation, including Group 133.

Drawing on Amnesty International’s prisoners of conscience model, Group 133’s Drapchi 14 campaign was designed to publicize the situation of the nuns and in so doing, to win their release. In an interview, one of the group’s organizers, Carl Williams, adopted a marketing metaphor to describe what they were doing. “If you want to use the marketing term ‘branding’ . . . to get a person’s name out there makes it much more difficult to torture or kill that person,” Williams told the Globe reporter (Cox 2002).

Williams’ comment about branding prisoners of conscience raises an interesting set of issues that are worth spelling out briefly. First, what does it mean for human rights advocates to articulate their politics using a commercial idiom? Like the subjects of countless human rights documentaries, the individuals represented on the Drapchi14 site are victims whose stories of suffering are meant to provoke our identification and to stimulate political action. Yet the way in which they are represented, through the techniques of celebrity and advertising, transforms their meaning. Or does it? Could it be that there are different ways of interpreting or decoding the relation between the form and the content, such that what strikes one generation as the “aestheticization of politics” strikes another as a new way to reconcile political goals and capitalist aims through a pervasive and influential medium? For those who have grown up in the post-1970s era, one marked by the growing presence of social marketing, is it a mode of political communication that is simply taken for granted? Do teenagers and twenty-somethings possess a different aesthetic, as Lev Manovich suggests in his writing on the use of Flash software in web design, than that of previous generations who located gritty politics in realist representation? Indeed, can we map the continuing evolution of technological and aesthetic strategies and the consequent production of new political forms in terms of generational shifts?

More work needs to be done on the link between the emergence of new commercial venues in which human rights testimonies circulate, for instance on MTV or in advertisements such as those for Benetton, and their forms of signification. Clearly, encountering testimonies in such contexts challenges our sense of that such material belongs in the so-called rational public sphere where citizens deliberate political issues. The question is how and whether deeply moral and politically contested issues can be meaningfully expressed in commercial culture using commercial language. Given that it is our language, how do we effectively suffuse it with meanings that resist the rhetoric of advertising, which is designed specifically not to tell the truth, or to convey complex or contradictory ideas? Does the option to “click here” merely position us as consumers who are choosing between predetermined possibilities online or is it meaningful way of taking “action”?

A second issue that is linked to the idea of branding victims of human rights abuses is that of efficacy. In No Logo, Naomi Klein (1999) examines some of the limits and contradictions of what she calls “brand-based politics” by which she means anti-globalization activism that focuses on individual companies such as Nike, Shell, McDonalds, or Starbucks. Klein notes that although targeting popular brand corporations has been successful, these sorts of campaigns can have unintended and contradictory consequences (e.g. with companies often spending more time and money on publicity than on internal reform, or people feeling they must consume more ethically, and not do much else). Similarly, by focusing a campaign on individual sufferers of human rights abuses who have been “branded” in a certain way on these sites, activists run the risk of freeing certain people but not necessarily achieving the long-term effect they desire – forcing governments to change their practices. For example, in recent years China has released several of the most well-known Drapchi14 prisoners on condition that they leave the country.[14] This is part of a much broader Chinese policy toward dissidents which enables the government to quiet western criticism of its poor human rights record without actually having to make major changes. Once the individuals are released, pressure is usually relieved on the PRC and attention focused elsewhere. Thus although activists are always extremely happy to be able to secure the freedom of individual dissidents, there are clear limits on deploying publicity in this manner.

- When you click, you are taken to the home page of Amnesty International’s Stop Torture campaign which includes images of several recent victims of torture and a brief paragraph stating AI’s position on freedom from torture as a fundamental human right. At the bottom of the page is a space to enter your email if you want to receive updates and appeals for action[↑]

- The most recent example of this is the case of Ngawang Sangdrol, a nun detained at the age of 13 for participating in pro-independence demonstrations in Tibet. The most well-known of the Drapchi 14 arrived in the United States in early April 2003 after having been paroled from prison by the Chinese for medical reasons. See www.savetibet.org for more information on her reception in the U.S. See also the book and accompanying CD-Rom of Rukhag 3: The Nuns for Drapchi Prison by Steven D. Marshall, available from Tibet Information Network.[↑]