Testimony as Documentary Evidence

The discovery and representation of information on human rights abuses through specific forms of realism is central to most human rights work. Indeed, human rights activists and organizations are first and foremost “collectors, filterers, translators, and presenters of information regarding human rights violations” (Keck and Sikkink 3). The underlying assumption is that the circulation of such information generates political action, whether it be through direct pressure on governments or corporations to change their policies, or through the mobilization of individuals on a grassroots level. Although the naive epistemology about exposure and revelation upon which this belief is based has been challenged in recent years by situations in which knowledge has actually failed to produce action, most notably the war in Bosnia and the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, it nevertheless remains a guiding principle of traditional human rights politics.

In the early years of Amnesty International USA (AIUSA), activists devoted a huge amount of their energy to gathering specific data about violations which they analyzed according to human rights principles and put in the form of written reports. These “thick rivers of fact” were circulated to governments and the press as evidence of their claims (Cmiel 1999). Activists’ reliance on “documentary rhetoric” (Hesford and Kozol in press) – realist forms of representation and conventions of documentation – presents a problem in that abuses are never clear-cut; there are always contradictions between human rights classifications of violence and how violence actually plays out on the ground. In order to manage the instability of the category upon which their claims are made, human rights activists formulate their reports using abstract universal discourses, and a particular style of journalistic realism. In his writing on human rights reports, Richard Wilson notes that the genre presents information as if it is simply factual and transparent; claims are supported with numerous references to how sources are checked, to international human rights standards, and to previous reports. By presenting their findings in this way, NGOs are able to appear credible (and their information objective) and in so doing to “cultivate a veneer of independence and impartiality in the international arena, which helps legitimize their assertions about the need for human rights norms.” 1

In recent years this orthodox insistence upon memory, revelation, and documentation has started to come under considerable pressure especially in the context of truth commissions, which some have argued enable a process of forgetting – rather than preventing them from forgetting – crimes against humanity and human rights violations (see Feldman 2001). This strand of research questions the relationship between witnessing, publicity, and collective remembrance, asking whether the more we know the more we actually forget.

Seeing is Believing: Handicams, Human Rights, and the News (2002), a documentary film directed by Katerina Cizek and Peter Winotick, is an instructive look at the role of digital video in documenting human rights abuses around the world. Filipino sociologist Alex Magno sets up the broader framework of the piece with his observation that video cameras are simply the latest in a long line of new communications technologies or “small media” that have played a critical part in various political revolutions around the world, from audio cassettes in Iran in 1979 to faxes in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to email and text messaging in the Philippines in 2002. 2

Gillian Caldwell, director of the New York-based human rights media organization WITNESS, elaborates on Magno’s point, underscoring the importance of video images gathered by activists as visual evidence of human rights violations. Drama is provided by the story of a Filipino activist named Joey who works closely with a group of indigenous people in the Philippines known as the “Nakamata Coalition.” We first see Joey training members of the coalition to document their struggles with local plantation owners over land in Mindanao, and then we see Coalition members take the camera out by themselves in order to document a meeting with outside officials. This practice of documenting oral transactions on video has emerged as an important one for indigenous people who view such transactions as contractually binding within their own societies. By videotaping discussions about land claims, for instance, non-literate activists have recourse to video records when agreements between parties break down. 3 Soon after the Coalition training process finishes, violence breaks out and the camera, provided by WITNESS, is there to record it all.

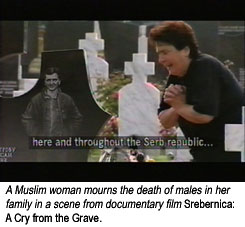

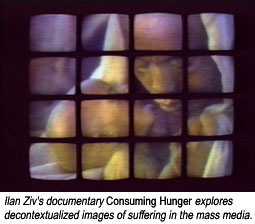

At the heart of this film is a theory of truth and transparency that is premised on two things: (1) the authenticity of experience (I was there, I witnessed it, therefore it is true) and (2) a commitment to the gathering and display of visible evidence. Yet as countless writers on documentary photography and film point out, the truth status of moving images has always depended on critical contextualization. Images do not accomplish meaning without framing, a point perhaps most starkly illustrated by the various readings of the Rodney King video footage elicited by the prosecution and the defense during the trials. 4 Ilan Ziv’s documentary Consuming Hunger (1988) further underscores the need for contextual information in order to educate audiences about what they are actually seeing. Although the transparency attributed to video evidence parallels that attributed to legalistic realist forms such as written human rights reports, human rights testimonials on film, or “cine testimonials,” can be distinguished by the use of explicit framing devices that supplement images with specifically targeted information aimed at provoking change.

- See Clark on the role of Amnesty International USA in the formation of international human rights norms.[↑]

- For more on this topic, see Annabelle Sreberny-Mohammadi and Ali Mohammadi’s seminal study of “small media” during the Iranian revolution; Calhoun on the importance of fax and CNN during the events in China in 1989; and Rafael’s essay on cell phone texting during the uprising against President Estrada in the Philippines in 2002.[↑]

- See Ginsburg for more on the use of video in indigenous communities.[↑]

- For more on the use of video in the Rodney King trials, see Feldman 1994, Nichols 1994, and Ronell 1992.[↑]