Coming Out

While Stefansson seems to have had a close relationship to his Inuit wife and son when in the field, once he was “out” he never publicly acknowledged his Inuit family. His denial, no doubt, is one example of a fairly common imperial response. At the time, white guests simply did not acknowledge intimate realtions with indigenous people if they had serious ambitions outside the colony. Not only did Stefansson’s Inuit connection defy prevailing attitudes toward “race mixing”, his prior engagement to a woman he met while in Boston, Orpha Cecil Smith, a Canadian student of drama (see Pálsson 2005), made things rather complicated. Stefansson, it seems, was anxious not to tell Smith about his Inuit son. Her father was religious and middle-class, a salesman of Canadian Mennonite background, and disapproving of his daughter’s relationship to Stefansson, a man who seemed destined for pointless and risky adventures among savages in the Arctic. Smith and Stefansson were engaged at the time Alex Stefansson was born. Inevitably, the long separation was taxing for their relationship. In Smith’s memory, Stefansson disappeared out of sight when he left for the Arctic although they were to meet again. They exchanged intimate letters throughout the three expeditions, to the extent this was possible due to the logistics of the expeditions and the sporadic nature of the postal service at the time.

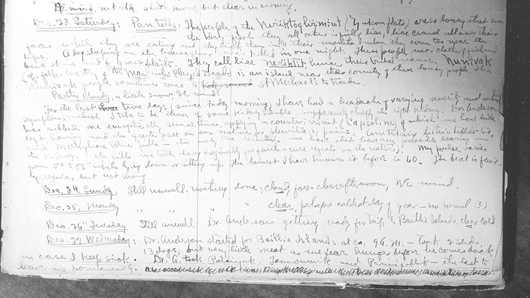

We do not know what Stefansson thought of his relationship with Pannigabluk and Alex as he doesn’t mention either a partner or a child in any of his writings. Some of his diary entries, however, indicate a rupture in his relationship to Pannigabluk (see Pálsson 2005: 88). On December 27 in 1911 he writes that Pannigabluk is leaving “permanently” (see Photo 3). He appears to have added something more to this, but later crossed it out carefully. Was it out of frustration? Could it be that Pannigabluk was leaving Stefansson for another man? Late in his career, Stefansson married a young woman in New York. His widow Evelyn (now Stefansson Nef) has sometimes attributed his silence on Alex Stefansson to the possibility that Pannigabluk may have been involved in sexual relations with another member of Stefansson’s expedition (Andersen). While such a claim may have relieved Stefansson and his widow of any responsibility with respect to his son and his six grandchildren, it seems unconvincing (see Pálsson 2005); many Inuit, including his grandchildren, suggest it was just an excuse. A recent article by Vanast (2007) turns the gaze onto Stefansson himself.

Vanast suggests that Pannigabluk may have left the camp in an angry mood, jealous because of Stefansson’s sexual liaisons with other women; while the evidence may be indirect, he argues, “comments by whites (when combined with dates on which one finds Stefansson in the company of certain wives) make for strong suspicion” (2007: 93). Prior to Pannigabluk’s departure, Vanast speculates, Stefansson had been involved with a woman named Mamayauk and her twelve-year-old daughter Nogasak. Stefansson had last seen Pannigabluk in March 1911 when he left for the Copper Inuit and when he returned in June “she was not there, but he did find Ilavinirk, his wife Mamayauk, their young daughter Nogasak, and another male. In July the men left for Baillie Island. … Stefansson was alone with Maayauk and Nogasak until, a fortnight later, Pannigabluk appeared . . .. That winter . . . Stefansson spent much time with Mamayauk (whose husband had returned) and little with Pannigabluk, who left the camp for good . . .” (Vanast 2007: 108, n. 13).

It seems that Stefansson sometimes arranged to have access to women other than Pannigabluk. Not only did he admit that he hired males who contributed little because he needed their wives as seamstresses, at one point he would spend time “drawing from his employees the names of the prettiest women in the Delta region” (Vanast 2007: 93). Whites claimed that he “chose men whose partners were renowned for their beauty, even ‘crazy’ men” (Vanast 2007: 93). One of the women in Stefansson’s entourage in 1915-1917 was a woman in her twenties, the wife of Walter Pikaluk who worked for Stefansson when 40-42 years old. Vanast continues in a footnote: “In mission records her name appeared as Bessie Poochimuk, Puchimuk, or Puchimirk . . .. It may be entirely unfair to Stefansson to note that he referred to her in his diary . . . as Pussimirk” (2007: 109, n. 14). There is a long tradition of Stefansson-bashing in Canadian academic circles. It may be tempting to see Vanast’s commentary as just one more example in this genre, echoing earlier debates about Stefansson’s flamboyant style, waste of public money, lack of judgment, and irresponsible behavior. Although the evidence discussed by Vanast is anecdotal and circumstantial and he may overstate his case, he nevertheless seems to have a point. It is quite likely that Stefansson’s silence about his Inuit wife and son had something to do with his complex involvements with other women in and out of the field.