Herschel Island

The early zoning of the earth into regions or culture-areas underlined Western ideas about borders, cultural differences, and the exotic. The “Arctic”, however, neither had clear boundaries nor a firm definition. For some, it represented anything beyond latitude 66°33′ north, for others it began with the tree line, and for still others it was identified by average temperature. For most Western whalers, early explorers, and anthropologists, the Arctic was a radical other. This was underlined by frequent references in Western discourse on the Arctic to “going in” and “coming out”, indicating that civilization ended where the Arctic began. Despite their othering of the people of the Arctic, European travelers often formed intimate relations with their indigenous collaborators, relations without which they would not have survived. The loosely defined Arctic Circle continues to be deeply enmeshed in the geopolitics of northern states and international bodies focusing on development, resources, and climate.

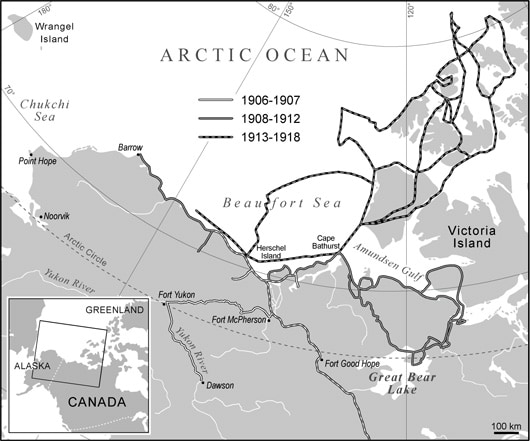

One of the key sites in the exploration and colonization of the Canadian Arctic was Herschel Island, located a few miles from the arctic coast close to the Mackenzie Delta (see Map 1). The number of guests who wintered there, mostly in relation to whaling, peaked soon after 1890, with approximately 1500 people. The Inuit living on or near the island provided European whalers with food and clothing in return for southern goods, including tea and sugar. Many accounts of local life dwell on stories of drinking and fighting. The main reasons for the expansion of the settlement at Herschel Island had to do with changes in fashion and morals in Europe. Among women of the aristocratic classes, wide and flexible dresses had increasingly been replaced by more firm and restricting clothes. Sometimes they were carefully tightened around the waist to underline the Victorian forces applied to women’s minds and bodies. Corsets, especially when strengthened by whalebone, baleen, were seen to be useful for this purpose. The French elite spoke of “Corps Baleine”. The growing market for corsets invigorated the whaling industry at Herschel Island. The price of whalebone increased and the operation of whaling boats became a lucrative business, even under the difficult conditions of the Arctic. Ironically, Victorian ideas about the clothing and constitution of women’s bodies were the driving force behind the development of the whaling community on Herschel Island, a community that apparently posed a fundamental contradiction to the virtues that the corset symbolized in Europe.

Over the years the whalers on Herschel Island—a mixed group of Whites, Afro-Americans, Siberians, Inupiat, and Cape Verdeans (“Portuguees”)—established a colorful, multicultural colony on Herschel Island. Hundreds of whalers arrived from the south, with their goods, languages, desires, beliefs, and diseases (notably measles, tuberculosis, and syphilis). There was racial tension between southerners as well as between guests and natives. In 1884, a few wives of whaling masters wintered on Herschel Island, along with their children. While this had a noticeable impact on social life, normally the whalers arrived without their families. Inuit males often worked as hunters or mates and Inuit women as seamstresses, either “on deck” or “below deck”, as “seasonal wives”. Suddenly, when the whaling stocks had nearly collapsed and hunting was no longer economical, they were all gone. In the process, however, Canada had expanded its empire. And for the Inuit life would never be the same. For almost twenty years, roughly from 1890 to 1908, Herschel Island was a frontier boom-town, known as “The Sodom of the Arctic”. Many of the European explorers and travelers who passed through here and elsewhere in the Arctic had native wives or concubines, including Peter Freuchen, Knud Rasmussen, and Vilhjalmur Stefansson.

One of the characteristics of the colonial era in the early stages was the relative absence of women in the colonies. This invited complex problems both at home and abroad. What rules should be applied to the intimate and the “private”? Often, the dark sides of colonialism—the tension between races, the problems of orphanage, and illegitimacy—were barely noticed. The mixed-blood children of colonial servants and native women posed a particular classification problem, a problem that usually was simply ignored. Stoler describes the silencing of emotions and passions and their consequences as “stubborn colonial aphasia” (2002: 14). Nevertheless, these were important issues in the biographies and histories of the colonial world. In some of the colonies, including the Dutch ones, European children were strictly forbidden to play with the children of servants of another race. Their moral strength, it was assumed, would be eroded if they began to babble in the native language. In the long run, this would lead to racial mixture that, in turn, would lead to the degeneration of the white race. Stoler’s work seeks to outline the “microphysics of colonial rule” (p. 7) through a colonial reading of Foucault, exploring “what cultural distinctions went into the making of class in the colonies, what class distinctions went into the making of race, and how the management of sex shaped the making of both” (p. 16).

Much of what Stoler has to say about empires, gender, race, and intimacy applies to the society of Herschel Island at the beginning of the last century. In particular, European women were rarely part of the teams of whalers and explorers. The likelihood of women visiting the Arctic in the early stage of colonizing was minimal, much less than in the case of the Tropics. The fiancées, wives, and children of European travelers invariably stayed behind, usually on the grounds that the environment and the tasks ahead were too tough for them. Native seamstresses on the other hand had an important role to play in exploration parties. Beside sewing warm clothes, preparing food, and taking care of camps, they provided company and sexual pleasures. Often guests and natives formed intimate relations and occasionally the guests married and decided to stay for good.