Some Background: A Generation

One of the most striking aspects of many of my parents’ passions, their love of books, the “Great Books,” their commitment to cultural institutions and the arts, their love of learning is that it is something they produce together. There is no precedent for these kinds of commitments in either my father’s or my mother’s family of origin. Although my mother’s parents went to college, they were not educated in the liberal arts. They were pharmacists. My father is the only one of his siblings to go to college, and neither of his parents had more than the equivalent of a high school education. For my parents, the children of immigrants, all of these enactments, the kinds of things I write about at great length in the first chapters of my book, are all more or less conscious efforts at self-creation, a part of the American Jewish identity my parents gave to me and to my brother.

The role of my father’s art in all of this is what is new here. It is a peculiar element in the larger tale I tried to tell in my book. Although the kinds of excesses expressed by both of my parents in engaging in the production and display of these images echoes the other excesses I describe as Jewish, there is something about this particular element in my family’s story that is different. To get at this I want to trace briefly some of the elements of my father’s childhood in order to illuminate his pivotal role in this particular legacy.

My father’s father was an immigrant tailor who came to this country as a young adult with few skills and little education. He was not an artist. No one in my father’s family made pictures. This activity was uniquely my father’s. As a child he made cartoons. He had a serial for the neighborhood kids about a character named Onion whose head was, appropriately, an onion. He later went on to illustrate his high school year book. Straight out of high school in 1944, he went into the army, an eighteen year old recruit. Eventually shipped off to Europe, my father sent home cartoons along with his letters. The impulse to draw was always there, growing stronger over the years.

Although my father always made pictures, his childhood was difficult and, without going into great detail, I want to argue that the precariousness of this past also came to shape the content and form of his picture making. It also helps explain the excess that continues to mark its production. My father’s family struggled during the Depression. His mother died when he was still a young child. The family eventually lost their home. Their living situation became increasingly precarious. If not for the support of their extended family, especially the siblings of my grandfather’s second wife Mary, the immediate family might not have been able to stay together during the most difficult of these times. What is striking is that through all of this, my father kept drawing, although the images were rarely displayed.

For most of my father’s life these images were housed in boxes. Like the family, they moved around. After leaving home, he relied on Mary and her siblings to make sure that his possessions were kept safe. The vast majority of my father’s pictures, along with his other possessions, remained in Mary’s care. She collected and held on to these things for the many years my father spent in the army and then, care of the GI Bill, attending various colleges and universities in and around New York State, from 1944 until he actually completed a degree and married my mother in 1958. 1 Mary’s youngest sister Paula, a young woman my father’s age, showed me her stash of his illustrated letters, cherished possessions she has kept for over fifty years.

Few of these early images were ever displayed or framed except when he placed a painting up on the wall of a bedroom that was his. Only after marrying my mother did these images came into their now familiar prominence. My mother insisted that he was an artist, that his pictures should be framed and on display.

Writing about these things is not easy. I feel protective, and yet this story and its urgency have shaped me. It has colored the way I see the world and most especially how I have come to understand family pictures.

The interplay between making art and its appreciation is a crucial element in my parents’ relationship. These highly gendered roles are a part of a more intimate contract between them. It also marks their literal vision of home. My mother is the person who most appreciates my father as an artist. As long as he continues to paint and draw, she makes sure that his works are properly appreciated. She is his patron even as she enables him in some sense to externalize a certain acceptance of his own efforts. Together they are the main audience for these works.

Entering into this intimate dance as an infant, the first child of this union, I had to find a place in this narrative. And so did my brother. Mirroring the gender roles of our parents, we played our parts. For us these practices were natural and normal; I have only just begun to unravel what all of this means to me, how this was neither natural nor normal.

Although initially my brother and I simply added additional support to my mother’s efforts at appreciating my father’s art, as my brother got older, he too began to draw and paint. Unlike our father, he did not do this as a child. He began making pictures as an adult after leaving home. And, although my brother’s pictures, his cartoons and drawings and many of his paintings look a lot like my father’s, they are quite different. For those unfamiliar with the intricate grammar of my father’s work and now my brother’s work, it might seem difficult to differentiate between the two. But we all know the difference. Members of the extended family, those pictured on the walls of the small room that was my brother’s bedroom, also know the difference. Part of being in this family, even our family of choice, is a certain connoisseurship. 2

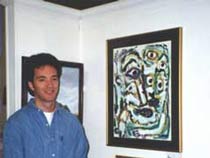

The things that generated my father’s art and its successful integration into the family, the affection and pleasure his images still evoke in us does not translate across a generation. Although my brother has come to produce his own faces, his own images, they have a different place in all of our lives. Although they are admired, they do not take up the same psychic or physical space that my father’s works have come to inhabit. Each of us experience my brother’s art as less homey. His faces are stranger, more distorted, less comforting. They are not images any of us want to live with on a daily basis, not even my brother. They do not seem to need such daily attention. They are most at home in exhibition spaces, ephemeral shows in public places.

Like my father, my brother is not a formally trained artist. He does not make his living from his art. But he has shown his works in public by now for over ten years. It was not until quite late in my father’s life that he began to show his work in public. In this case, I am interested in the distinctions between my brother’s and my father’s relationships to their art as a way of learning something different about issues of identity and home, the subject that has been at the heart of my own work.

- It should be noted, as I suggested earlier, paintings and drawings were not my father’s only prized possessions. There were also short stories, plays and poems that he had written, and books, lots of books, the beginning of a life-long collection of first and rare editions of mostly twentieth-century American literature. These are some of the books on the shelving unit described earlier in this essay.[↑]

- This was especially evident at the first joint show they did in the early 1990s in Dover, Delaware. At this event, Julie Locke, then a very young child, was able to tell other guests at the opening which pictures were done by which artist. Even she knew. My father and brother are scheduled to do another joint show scheduled for March 2003, at the Delaware Theater Company in Wilmington, Delaware.[↑]