Again, my history of multiple displacements has prepared me to conceive of identity as fractured and self-contradictory, as inflected by nationality, ethnicity, race, and history. But it has also made me appreciate those moments of commonality which allow for the adoption of a voice on behalf of women and for the commitment to social change.

–Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames (238).

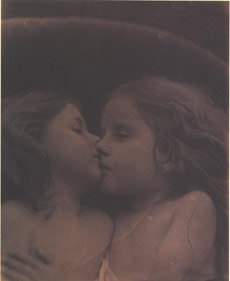

Cameron’s pictures are haptic in the fullest sense of the word. Not only did she physically scrub, scratch, brush, and fingerprint her glass plates, she also focused on the ways in which women touch.

–Carol Mavor, Pleasures Taken (48).

The Familial Gaze is a book about longing and the desire for community and connection. By presenting carefully imbricating accounts of a series of intimacies, it also enacts such a vision. Through essays and images, this collection offers readers different ways of seeing those all too familiar images of the family, Madonna and child, husbands and wives, lovers and friends.

In a moving account of the Madonna photographs taken

by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-79) 1, art historian Carol Mavor offers a detailed description of the construction of these particular familial images. Mavor presents Cameron’s multiple roles as artist, photographer, stage director, hostess, matron and literally the developer of the Madonna prints. As Mavor explains, it might be best to think of these photographs as playful and yet ever so carefully orchestrated communal productions. “Not only was Cameron a performer, she was also a stage director. She insisted that her guest be actors for her camera” (45). In other words, Cameron’s images emerge out of the warmth and excitement of her engagement with others in the comfort of her home.

Cameron was not a typical Victorian matron. Instead, beginning at the age of 48 when her own children were all grown, she transformed her home into what one guest described as “the funniest place in the world.” 2 It was the place where Cameron directed family members, invited guests (often famous artists and writers of the period) 3 and household servants to star in her productions. In these visual dramas, “Even the maids and cooks were exposed as Virgin Marys, Ophelias, Beatrices, and mountain nymphs”(46). Most of what became known as Cameron’s Madonna pictures were in fact photographs of her parlor maid, Mary Hillier. 4

I begin this afterword by recounting some of these stories about the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron in order to look at Marianne Hirsch’s role in the creation of The Familial Gaze from a slightly different angle. Like Cameron, literally and figuratively, Marianne Hirsch’s fingerprints are all over this volume. It is both a testament to her generosity and hospitality as well as her critical engagement. Hirsch not only hosted the conference and co-curated the exhibit that were the beginnings of the volume at her home institution, at that time she also carefully constructed the critical framework through which each of the photographs and papers were to be read. 5 In The Familial Gaze, Hirsch now invites a broader readership into a conversation about family pictures and their allures. She offers readers entry into a conversation among intimates. Through the volume we become a part of this critical conversation.

By gathering an eclectic group of literary scholars, art historians, curators and artists some of whom are in fact Hirsch’s own dearest friends and family members, 6 she asks readers to reflect on our own family pictures. She also asks us to reconsider what constitutes “the familial gaze.” Through the volume we are invited to look at these intimate engagements as a public practice. Hirsch’s touch also marks the volume in other ways. There is, for example, a powerful continuity between the themes of this collection and Hirsch’s previous work. As in The Mother/Daughter Plot, here again she is engaged in the task of opening up familial discourse to critical interrogation. 7 And here too she does so out of a desire for a different kind of critical feminist community. For Hirsch such a community must be able to address larger historical legacies. For Hirsch this means imagining a community that can embrace her own family history, what she has referred to elsewhere as her “displaced girlhood.” 8

In The Familial Gaze all visions and versions of the familial are haunted by historical traumas, displacements, promises and disappointments. Here again, such legacies cannot be seen as separate or distinct from even the most private of images or recollections. Thus, the legacy of slavery and racism in America looms large over many of the volume’s essays, including those by Smith, McDowell, Chong. Wexler, Willis, Abel and Liss.

The works by Spiegelman, van Alphen and Spitzer are each, in different ways, about the Shoah and its visual legacies. Pieces by Sultan, Novak, Miller, Gallop and Leonard offer insights into a postwar American landscape of disappointed promise especially for American Jews. And, as I read it, through the dark shadows of not only the Holocaust but also America’s ongoing racial prejudice, many of the essays in the volume speak to the urgency and impossibility of assimilation into an ideal picture of the American family.

The collection as a whole does not allow readers to take comfort in any simple reading of the family anywhere as a respite from history or politics. There is no such thing as “the family” in postwar America nor is home easily found in the promises of European cultural inclusion or class mobility. These ambivalent legacies demand that we see “the familial gaze” as self-contradictory. Like identity it too is inflected by nationality, ethnicity, race and history. Despite and because of this, Hirsch asks us not to give up on community. Instead she argues that even her own family history as viewed in relation to the images and narratives of many others can be generative. For her it seems this means that we should consider appreciating all the more those rare moments of intimacy and connection wherever they occur.

I read this volume as such a moment. In The Familial Gaze Hirsch extends the feminist vision of her earlier work across disciplines and critical practices to create an intimate community of inquiry. In reconsidering the power and allure of family photographs, the collection demonstrates what can happen when these stories and images are shared. In the process of exchange, a different kind of intimacy is enacted. In the public space of an academic conference, an exhibit and a volume, Hirsch blurs the boundaries between public and private images and domains. By gathering the voices and visions of a broad range of scholars and artists and placing them in conversation with each other, Hirsch extends our notion of who is familiar. By queering these boundaries in the construction of the volume as a family album, Hirsch enacts a different kind of intimacy. She opens up the familial gaze.

- Carol Mavor, Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), Chapter Two, “To Make Mary: Julia Margaret Cameron’s Photographs of Altered Madonnas,” 43-70.[↑]

- Mavor, Pleasures Taken, 46.[↑]

- “A great entertainer, Cameron regularly invited famous people to her house, from Alfred Lord Tennyson to Lewis Carroll and Charles Darwin.” Mavor, Pleasures Taken, 45.[↑]

- Through these images, Hillier became known as the “Island Madonna” by the local people who lived near Cameron’s house. Mavor, Pleasures Taken, 43.[↑]

- This was the “Family Pictures/Shapes of Memory” conference held at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., in May 1996. Along with the conference there was a photography exhibit called “The Familial Gaze,” on view at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. My comments reflect the mood and tone of these festivities. At these events, not only speakers, artists and those with official positions were welcomed into any number of discussions. It was my pleasure to attend this conference with my colleague and friend Ruth Ost. We continue these conversations in Philadelphia where I have begun work my own next project, a book about American Jews and family photographs, tentatively entitled Picturing American Jews: Photography, History, and Memory and Ruth is working on a series of articles on feminist art and the uses of photography focusing on specific works by Hannah Wilke (the Intra-Venus series), Helene Aylon (“the Women’s Section”), and Sally Mann (Immediate Family).[↑]

- Some of those in attendance were close friends and/or partners. These included Jane Gallop and Dick Blau, Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, Mieke Bal and Ernst van Alphen as well as long time feminist friends and colleagues, Elizabeth Abel, Nancy K. Miller, Jane Gallop and Marianne Hirsch. Particularly noteworthy at the conference were interactions among and between Gallop, Miller and Hirsch. For an earlier exploration of these intimate and critical interactions, see Jane Gallop, Marianne Hirsch, and Nancy K. Miller “Criticizing Feminist Criticism,” in Conflicts in Feminism, Marianne Hirsch and Evelyn Fox Keller ed., (New York: Routledge, 1990), 349-369. Also in that volume is a powerful essay by Elizabeth Abel that connects back to the themes of her essay in this volume, “Race, Class, and Psychoanalysis? Opening Questions,” Conflicts in Feminism, 184-204. I would also like to note that Marianne Hirsch’s parents and two of Joanne Leonard’s sisters, Barbara Handelman and Eleanor Rubin, also attended the conference and were a part of these discussions.[↑]

- Marianne Hirsch, The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989).[↑]

- See Hirsch’s Family Frames. The chapter “Pictures of a Displaced Girlhood,” is an expanded version of her essay by this same title first included in Angelika Bammer ed., Displacements: Cultural Identities in Question, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 71-89. This early publication of the essay along with the haunting photograph on the cover of her Mother/Daughter Plot offers readers glimpses into Hirsch’s ongoing interest and fascination with intimate looking and family photographs.[↑]