Just as the white upper classes took to slumming it in the Harlem nightclubs and jazz joints, French high society—as pictured in the film—would slum it in sailors’ joints and bars. Analysts of the racial and colonial imaginary of France in the 1920s and 1930s often fail to note that the film also portrays “the people.” Such vignettes of popular Parisian life are recurrent during this period. This inclusion should be stressed as an element that complicates a mere reading of “the French” as all embodying the same degree of colonial arrogance and racist bigotry. In Zou Zou, for example, Jean Gabin, who plays a sailor, belongs to le petit peuple. While taking part in the colonial venture, he participates in it differently than the young engineer of Siren of the Tropics. Class distinctions are also part of the complexity of the portrayal of the racialized and sexualized body within the colonial imaginary.

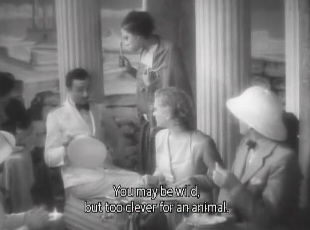

In Princess Tam Tam, commonplaces about civilization and savagery, nature and culture abound, such as this fragmented dialogue with a gardener that seems crudely out of place. The gardener utters peremptorily: “African flowers are not made for salons,” as an answer to Coton’s earlier crude statement that “manure is natural.” The Orient and the Occident are systematically and simplistically opposed in a cross-satire of civilized man and the fake exotic. When in one of the early Tunisian scenes Alwina joins the aristocratic picnickers, she replaces the salt with sand, spoils the dainty food, and forces the group to abandon its table manners.[video] She plays a trick on the colonists reminiscent of the slave’s trickster tales. Then one of the closing scenes, in which the maharajah reveals to Alwina the impossible dream of participating in Western values (as Max de Mirecourt and his wife embrace in a car) while the Orient beckons in the “shape” of Tahar, is comically overdramatic. Alwina must give up on her “desire” to blend into “civilization” through assimilation, and go back to her native land where she belongs. The viewer must remember that this desire is only explicit in the fictional sequence of the film. The film narrative also portrays her as longing for home in her Parisian apartment as she listens to music that reminds her of her country. Indeed, the Parisian apartment contains fake flowers and palm trees, much to Alwina’s amazement. True and false, authentic and fake, are stereotypically distributed as attributes of nature or civilization.

The reviews of La Revue Nègre emphasized Baker’s link to the primitive. The fantasy of transformation, metamorphosis, and makeover, which nevertheless leaves the instinctual untouched, is still underlined by reviewers when she becomes a film star: “Today’s Josephine Baker owes a lot to the Harlem adolescent imported into Europe: the flavor of the same brutal spices burns under the skin of the educated star, plied to more civilized tricks” (Alexandre Arnoux, Nouvelles littéraires, M, 25). The rhythm of the conga that calls Alwina back to her natural primitive dancing frames the film, as it is featured in the opening sequence, underscoring the title of the film “Tam Tam” or Tom-Tom, another name for the conga, a drum of African origin derived from Congolese makuta drums. 1 The narrative sequence corresponding to the end of the novel thus shows that she must go back and ends on the failure to “educate” Alwina: the spring cannot be tamed. This failure echoes in reverse the earlier failure of the writer whose inspiration has dried up—his wife screams: “Failure, failure, you are a failure”—which once again sets civilization against instinct. A caricature of the failed novelist, Max has written the novels Coeurs en flammes, Ame trouble, and Les Déclassés, whose titles reflect on the (poor) quality and the genre (popular romance) of his writing. In sum, Max’s literary success is due to the coincidence of his story’s correspondence with the advent of modernism: the savage’s revenge on civilization.

The other ending, the film’s ending, is a closure that ironically “seals” the fall of civilization in a burlesque mode.[video] “Returned” to Tunisia, Josephine and the exotic Tahar become a couple and have a child together. Tahar throws a clay pot and plays with the infant while Alwina wanders through the colonial villa, given to her by Max, that she has transformed into a chicken coop, where ducks and a donkey impose the reign of the animal and represent the free. Domestic bliss is instituted where it was not expected, as the film started with a Parisian domestic row. The French urban and upper-class plot is relocated in the African landscape. The spoiled aristocrats of the City of Light give way to a Tunisian family idyll. Much has been said about the fact that Baker never ends up marrying the white man in the films that were written to promote her stage success, including in the Mémoires. 2 Baker, however, did marry Jean Lion (1937) and Jo Bouillon (1947) in real life: “As for me, Whites did marry me” (M, 241).

- The congas used in Cuba are called the tumbadoras. From African instruments of Ashanti, Fan, Bantu and Yoruba origin, they are the product of the creolization that derives from the migration of African peoples during the slave trade. These instruments, like many other percussion instruments, have benefited from a considerable number of improvements to achieve the desired form and tension.[↑]

- “If I don’t get love, I will get a name … Bird of the Islands” (M, 158).[↑]