The Pixar/Disney film Wall-E (2008) presents a dystopian vision of the future, where Earth has become overwhelmed by trash and pollution due to a culture of excess consumption, forcing humans to evacuate the planet and live in a starliner traveling in space owned and operated by the megacorporation, Buy n Large. Wall-E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter—Earth Class) robots were left behind on Earth to clean up the mess; one of these Wall-E robots remains in operation and dutifully continues working. The remaining Wall-E has developed an elaborate “life-like” existence on Earth, collecting knickknacks from the trash piles, self-repairing from defunct Wall-Es, befriending a cockroach, and watching Hello, Dolly! and pining for love. If Earth is burdened with trash, the remainders of excess consumption, human beings are burdened with a different kind of remainder—fat. The people that populate the starliner are represented as pathetically fat, bones atrophied to the extent that they have limited mobility, reliant on robots for everyday tasks, and blissfully unaware of their tragic dependency. Fat represents modernity gone awry. A series of portraits of the ship’s captains over the years neatly sums up humanity’s evolution, or devolution, as it were: each captain gets fatter and fatter, signaling the toll that the Buy n Large lifestyle has taken on people’s bodies. 1

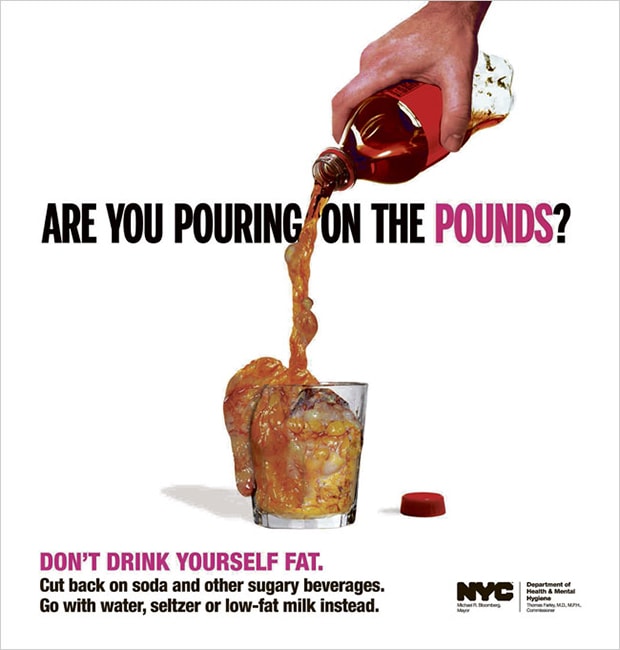

Wall-E‘s dystopian future imaginary is strikingly in concert with both contemporary policy directions and scholarly accounts of fat. For one, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s recent attempt to ban the sale of large sodas in the city might as well have been called the “Buy n Large” ban, an attempt to save fat humans from themselves. Second, scholarly literature from a range of fields increasingly points to the environment as a primary factor in the distribution of fat throughout populations. These “obesogenic” accounts, as they have become known, point to structural conditions that facilitate some choices over others. Swinburn et al. define obesogenic as “the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities, or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations.” 2 Obesogenic accounts may point to issues such as the availability of grocery stores and farmers’ markets, versus, say, fast food restaurants, in a given community, or agricultural policy that encourages a reliance on things like high-fructose corn syrup. Obesogenic accounts also point to the built environment, highlighting the availability of parks and recreational facilities, neighborhood walkability, and neighborhood safety. The general idea behind obesogenic accounts is that while people may have a certain degree of choice in their lives, what people choose for themselves is significantly constrained by the options available. As one team of researchers insists, “To combat the epidemic of obesity, we must first cure the environment.” 3 For proponents of the obesogenic perspective, context is everything.

Among other things, Wall-E queries what constitutes life; the film’s presentation of lifelike robots and thing-like humans recalls Donna Haraway’s assertion that “our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.” 4 The question of what constitutes a life in relation to fat is explored by Lauren Berlant in her essay, “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency),” as well as in her most recent book, Cruel Optimism, which includes a version of this essay. Berlant defines slow death as the “the physical wearing out of a population and the deterioration of people in that population that is very nearly a defining condition of their experience and historical existence.” 5 Slow death is “embodiment towards death as a way life,” in which “life building and the attrition of human life are indistinguishable.” Berlant’s notion of slow death raises the question—what constitutes a life? And what does fat have to do with it? What is it about fat that seems to magnetize fears around living and dying, life and death, liveliness and … deathliness?

In the inevitable slide from fat to the biomedical category of “obesity” to future illness and death, quite a bit of nuance is sacrificed along the way, and fat is excised as antithetical to life and liveliness. In a Fat Lip Readers’ Theatre bit, a performer notes, “My grandmother died not long ago at the age of 85. They put ‘obesity’ as the cause of death on her death certificate. Just how old does a fat person have to get before they are able to die of old age?” 6 Fat becomes a matter of probability and risk, indicating likelihood of disease and death, but fat is also risk coming to conclusion. We could consider fat as marked by the temporality of what Sarah Lochlann Jain has termed, “living in prognosis,” and what Jasbir Puar refers to as “prognosis time.” 7 Puar notes that within contemporary biopolitical frames, “identity is understood not as essence, but as risk coding.” 8 Risk coding suspends us in anticipation, or, in “a lived condition or orientation [that] gives speculation the authority to act in the present.” 9 Increasingly, speculation is given the authority to act in the present on both an individual level and a population level, with widening circles of stakeholders. While the mantra of individual responsibility remains as strong as ever, obesogenic accounts provide a justificatory premise for interventions aimed at populations, often through mechanisms of local, state, and federal government.

Recently, feminist and queer scholars have argued for an obesogenic perspective on fat. In a 2006 article in Signs, Antronette Yancey, Joanne Leslie, and Emily Abel plead with feminist scholars to take obesity seriously, and to recognize our obesogenic environment and its deleterious influence on women’s health, particularly the health of women in poor communities of color. 10 Elspeth Probyn, in “Silences Behind the Mantra: Critiquing Feminist Fat,” indicts obesogenic environments, highlighting developments in agribusiness and their impact on poor communities. According to Probyn, “There is much at stake: both in the West and in developing countries the effects of obesity are causing medical and emotional havoc; the widespread demand for ever cheaper food is destroying the environment and people’s lives.” 11 She decries what she terms the “feminist cultural critique” that defends fat as resistance and fails to address a situation in which “people are increasingly terrorized and seriously damaged by what they eat,” she argues. “There is something seriously wrong with an analysis that leaves untouched the socioeconomic structures that are producing ever larger bodies,” Probyn argues. 12 These examples, as well as the work of Lauren Berlant discussed below, are dramatically different in terms of approach, tone, and scope, but they share a key contention in common, the insistence on obesogenic environmental explanations of fat that produce divergent consequences for less-privileged communities.

In this essay, I begin with a rumination on (un)liveliness through an examination of critical responses to the film Precious (2009) as a way of thinking fat in relation to Sianne Ngai’s concept of racial animatedness. I argue that while the racial and ethnic other is marked by animatedness, as Ngai suggest, the fat racial and ethnic other is marked by a certain suspension of animatedness, or torpidity, in both its affective and physical register. In the next section, I examine Berlant’s arguments regarding obesity, slow death, and lateral agency in concert with other obesogenic environmental accounts. If fat embodiment is marked by torpidity, or a certain suspension of animatedness, it is also marked by absorption, as in environmental absorption. How does the notion of environmental absorption become a mechanism of racial, ethnic, and classed difference in these accounts?

- Before the storyline was fully mapped out, the film’s creators initially envisioned these bodies as pure protoplasm. The creative team referred to them as “The Gels,” as one creator put it, the characters were “completely devolved, gelatinous, boneless, but still cute!” The team used molds filled with Jell-O during early filming to achieve a “jiggling” effect, “We videotaped it shaking. We would spank it and you’d see it jiggle.” The team also wanted The Gels to sound as “shaky” as their form; they wanted voices “shimmering, shaky with vibrations in it,” asking themselves, “What would a blob of jelly sound like?” In the end, however, they found that The Gels were not very relatable. The creative team worked to address this, giving The Gels ears, noses, legs, and “stubby fingers;” they become human, but “big, round, cute, innocent, unaware,” “like a baby.” See Captain’s Log: The Evolution of Humans, DVD featurette, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment (2008).[↑]

- Boyd Swinburn et al., “Dissecting Obesogenic Environments: The Development and Application of a Framework for Identifying and Prioritizing Environmental Interventions for Obesity,” Preventative Medicine 29 (1999): 564.[↑]

- James O. Hill and John C. Peters, “Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic,” Science 29 May 1998: 1373.[↑]

- Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991): 152.[↑]

- Lauren Berlant, “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency),” Critical Inquiry 33 (2007): 754.[↑]

- Cited in Burgard and Lyons, “Alternatives in Obesity Treatment,” Feminist Perspectives on Eating Disorders (New York: Guilford Press, 1994): 212.[↑]

- See Sarah Lochlann Jain, “Living in Prognosis: Toward an Elegiac Politics,” Representations 98 (2007): 77-92.[↑]

- Jasbir Puar, “Prognosis Time: Towards a Geopolitics of Affect, Debility and Capacity,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19.2 (2009): 165.[↑]

- Adams et al., “Anticipation: Technoscience, Life, Affect, Temporality,” Subjectivity 26 (2009): 249.[↑]

- Yancey et al, “Obesity at the Crossroads: Feminist and Public Health Perspectives,” Signs 31.2 (2006): 426.[↑]

- Elspeth Probyn, “Silences Behind the Mantra: Critiquing Feminist Fat,” Feminism & Psychology 18 (2008): 402.[↑]

- Oddly setting up “feminist fat” as her object of critique in her title, it is not always clear who Probyn is so annoyed by, or what they have in common, but it is abundantly clear what she thinks of the group. What is “feminist fat” according to Elspeth Probyn? Feminist fat is ignorant of foundational research; feminist fat is not trained to do media analysis, and is not very good at textual analysis either; feminist fat states the obvious and complains; feminist fat disappoints Foucault. Bad feminist fat, indeed. Probyn invokes blogger Jennette Fulda and her blog “PastaQueen” and two articles published in the same issue of Feminist Media Studies as representative of this nebulous field of feminist fat activism and research. The “mantra” that Probyn’s title refers to is “fat is a feminist issue,” and she notes that Fulda was unaware of this phrase’s origin as the title of psychotherapist Susie Orbach’s 1978 book on compulsive eating. It is worth noting, however, that Fulda’s blog, now retired, was “a weight-loss blog that chronicled [her] journey as [she] lost 200 pounds”—hardly a poster blog for militant feminist fat. Probyn’s claim that “many today are surprised to learn that [fat is a feminist issue] originated as a title” may be true in a general sense, but I would put my money, and a footnote, on fat activists and fat studies scholars knowing the book pretty well.[↑]