The Genealogy

Why start such a genealogy of performance art in the Eastern European context by connecting it with feminism? The relationship between performance art and feminist activism is, according to Eleanor Antin, constitutive for performance art: “practically, it was the women of Southern California who invented performance.” 1 The Western genealogy of performance as an effect of feminism, according to Antin, has its roots in guerrilla theatre and in the university and street riots of the American women’s movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

The history of performance, as well as the history of feminism and queer politics, is actually a history of battles, nothing is given, and it must not be taken for granted.

In contrast to what Antin suggests, in the context of the former Yugoslav territory, I can state that performance in connection with feminism is deeply linked to art practices such as the body art and conceptual art of the 1970s, and the post-conceptual tradition and alternative or underground movement of the 1980s in Ljubljana. What does such a change imply? It is clear that public space under socialism belonged to the Communist Party and that it was necessary to find another space—precisely to develop and take back the space of contemporary art and culture. The notion of performance therefore finds its productive meaning, paradoxically, in the area of aesthetics and drag culture in connection with political activism.

Beatriz Preciado, in her newly rewritten genealogy of performance art within the Western context, introduces three levels of the dramatization of female sexuality, and I will add performing politics in relation to (post)feminism and queer positioning. My thesis is that not only can we discover, outline, and read a similar genealogy of dramatization, as it is presented by Preciado, in socialism as well as in the postsocialist context of the former Yugoslav space, but even further, we can learn about changes in the paradigm of queer strategy in our contemporaneity.

Preciado talks about the dramatization of sexuality as a three-stage process that develops from heterosexual to drag, and in the end, enters queer space.

In 1970s Zagreb and Belgrade, we witnessed: (1) The dramatization of heterosexual femininity. In the 1980s, within the underground or alternative movement in Ljubljana, we witnessed; (2) The dramatization of femininity in gay culture and later in the 1980s and 1990s in the postsocialist context (under the influence of media art and new performance), we witnessed; (3) The dramatization of masculinity in the queer context of Eastern Europe. Therefore, the specific genealogy of performance and feminism under socialism and the postsocialist context bridges body art and conceptual art with the underground and punk/rock ‘n’roll movement displaying the passage that I will define as being from sexually queer to politically queer.

Capital functions as the evacuation of different spaces; it presents a constant production of “universal,” abstracted, standardized nonspaces. The world becomes unified, easily “understandable,” and even more importantly, easily exchangeable—a transparent machine for the production and circulation of skills, technologies, and organizational models. Global capitalism functions by installing the iron law of sameness everywhere in the world, which is why we talk about the global world! Other worlds and other spaces (that are not part of the First Capitalist World) and their histories and theories, practices, and activities are evacuated, abstracted, and erased. This is why talking about the new political subject of performance via (post)feminism and queer identity today means linking it to different new spaces of battle and engagement. Or, as stated by Brian Carr:

And though this is a history that can never be summarily rescued, a politically invested critical practice cannot suffice to leave it or the subaltern nonsubject in the space of a theoretically foreclosed real, insultingly lamenting it as a hapless loss on which the symbolic must be founded. Such a position only fetishizes the symbolic itself, remaining hinged to a symptomatic of unilateral intelligibility where what appears unrepresentable is forever and essentially so. Indeed, the very positing of the unrepresentable, its very “appearance,” is itself a political production, one that cannot simply be chalked up to the unfortunate “reality” of symbolic intelligibility. It is, after all–and I say this realizing the risk in such a designation–our responsibility to think the symbolic differently, refusing at every turn its supposedly immutable and a priori codes. 2

I would like to proceed not with a simple illustration, but a conceptualization of the proposed three levels of dramatization in order to politically rethink performance art and transfeminism.

1. The dramatization of heterosexual femininity

Sanja Iveković, Zagreb

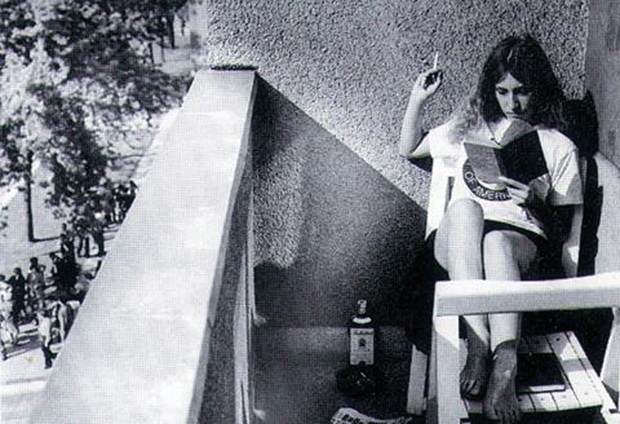

Sanja Iveković from Zagreb (Croatia) asked, in her works, for the repoliticization of the most intimate heterosexual inner space. In 1979, she developed a performance piece to be staged the day former-Yugoslav president Tito (who died in 1980) arrived in Zagreb for an official visit. The piece was called Triangle, as in a triangulation of the symbolic, the real, and the imaginary. Iveković appeared on the balcony of her flat in the center of Zagreb at the same time that Tito’s car was passing and a crowd of onlookers stood cheering below on the street. While Tito passed, Iveković read a book while pretending to masturbate. Her actions caught the attention of a secret service officer on a nearby rooftop. Soon after, a policeman or the neighbor rang her doorbell asking, “that persons and objects should be removed from the balcony.”

Triangle consists of 4 photographs: Iveković on the balcony, two are with Tito’s car passing and the crowd cheering him, and the fourth shows the secret service officer on a nearby rooftop.

In Triangle, Iveković transgressed masculine public/political space while dramatizing heterosexual femininity; with this act of female autoerotization “playing the woman,” she masked and softened her performative entrance in the public space, which in socialism has historically belonged to men. This performance resulted in the creation of agency in two ways. It provided a cultural interpretation of the formation of femininity and it was a reflection on the division between private and public spaces. What Iveković performed is what is today interpreted as the “masquerade,” a distinction between genuine womanliness and the public space. According to Preciado the prematurely developed postmodern notion of the masquerade was very influential in twentieth-century analyses of the dramatization of heterosexual femininity. The point not to be lost in this interpretation is that Iveković is not only performing what is to be seen as a (heterosexual) woman for the male gaze, but also the division of private and public spaces. Without the text, the textual narrative about the work given by Sanja Iveković, the work would have a very narrow meaning for the general public. Through the text, the work became a stage for performing gender and private/public spaces. Or, the autoerotization (the masturbation in 1979 by Sanja Iveković, as she explained) still presents a serious problem; women’s sexual actions still do not have the universal male self-explanatory discourse that allows for identification and understandings per se. Women’s autoerotization, as argued by Jacqueline Rose, presented a serious problem; therefore, women artists had to “make up” a good story. Sanja Iveković presented the best one—who could ever think of forbidding the image of totalitarian president Tito, even if it was stained by precisely performed discursive masturbation?

According to Judy Chicago, dramatizations of heterosexual femininity were always aimed at transforming the limits between private and public space, aiming at what was referred to in the United States as a process of consciousness raising. 3

Vlasta Delimar, Zagreb

Vlasta Delimar from Zagreb (Croatia) is one of the most important female performers in the former Yugoslavia. The beginning of her career can be traced back to the phenomenon of the so-called new artistic practice, a complex artistic conceptual movement in 1970s Croatia. Her artistic work includes, among others, repainted photos and photomontages that all focus on a single heroine: Vlasta Delimar herself. With her narcissistic gestures, so utterly self-centered that she functions at the same time as a sign and icon, Delimar stages the now already internalized awareness of constant self-control, or better yet, the notion that we live as if we were about to be photographed. In these still postsocialist, transitional times, when pure blood and tribal affiliation are existential paradigms in a transitional period of former Eastern European space, I can talk about Delimar as a “bastard,” an illegitimate person.

Sexuality clings to the female body, says Monique Wittig, so why should we try to get rid of it? 4 In Delimar’s attempts to articulate the desires of the Other, she may in fact be presenting herself as housewife and whore at the same time, yet remains far away from conventional roles. The interesting thing about her work is not so much related to gender, but to sex and sexuality in performative terms, allowing us to make a connection with the early works of performance porn actress Annie Sprinkle.

Vlasta Delimar’s work can also be seen as a subversion of the Catholic morality that is the dominant regulator of social, moral, and human norms in Croatia—and I can state this for all the countries of so-called Central Europe, Slovenia and Austria included. 5 In this context she intervenes with “direct speech,” through titles such as, “I love a dick,” etc. The next important moment is her “rough, genital nakedness” in opposition to the “non genital, shaved” and therefore esthetically tolerated nakedness and sexuality.

It seems that from the so-called capitalist outside, and in relation to stereotypical views on “ex-socialist or ex-communist women,” they seem to have an extra ability to denude themselves, showing their lives unmediated, bare and without veiling. But via Delimar’s work, as pointed out by Šuvaković, we see that naked or bare life is never performed as such, but always through sophisticated technological and new media representational and communication regimes, practices, and power relations (photography, video, Internet). Just think about Google Earth’s “reality show” of Africa’s Darfur tragedy, around-the-clock, bare or naked life, “live” on the net. This is made possible only through sophisticated technological and new media representational and communication tools that regulate visibility and show nothing but death as their “brand” of authenticity.

- Eleanor Antin, quoted in Preciado 2004.[↑]

- Carr 2004: 143.[↑]

- Judy Chicago, cited in Preciado 2004.[↑]

- Monique Wittig, “The Category of Sex,” Feminist Issues 2.2 (1982): 63–68.[↑]

- Miško Šuvaković, Cases’ Studies (Pančevo, Serbia: Mali Nemo, 2006). All references to M. Šuvaković’s arguments and thoughts are from this book.[↑]