Argentina legalized abortion in December 2020 after years of popular mobilizations, delivering a historic victory to the movement Ni Una Menos (Not One Less). 1 In Poland two months prior the Constitutional Tribunal ruled in favor of a near total ban on abortion, casting a major defeat for the Strajk Kobiet (Women’s Strike). 2 Three years later, the 2023 elections in Argentina brought in far-right populist Javier Milei and, with his administration, a threat to the country’s hard-won abortion rights, among other political and economic shifts. In another reversal that same year, Poland elected Donald Tusk and ousted former far-right prime minister Jarosław Kaczyński. While the new government under Tusk is now considering easing the country’s strict abortion laws, challenges persist as the former prime minister’s national-populist Law and Justice party continues to exert influence over constitutional courts. As abortion and other reproductive healthcare issues are weaponized in national politics and the landscape of reproductive justice faces dramatic and often polar shifts around the world Argentinian and Polish feminists have found practical and symbolic expressions of solidarity through the invocation of the witch.

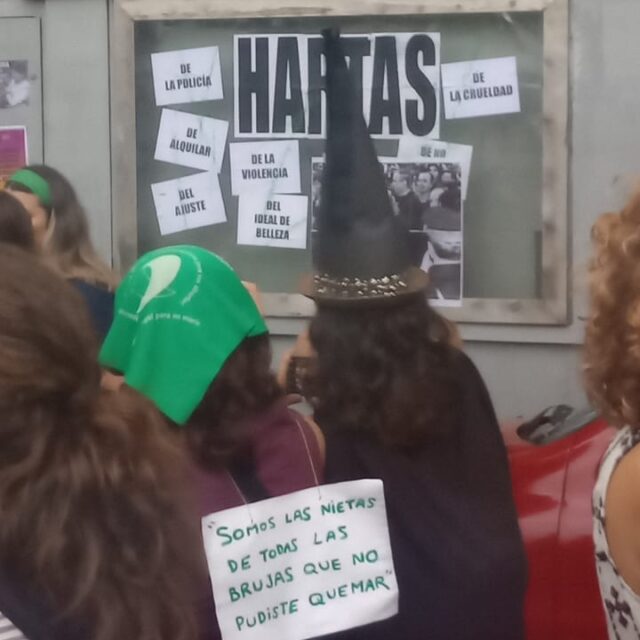

The figure of the witch has inspired feminists around the world, beyond Argentina and Poland. “We are the granddaughters of the witches you could not burn” is a common slogan seen and heard at protests in Madrid, Istanbul, Santiago, New York, and beyond, connecting feminists across disparate geographies and histories. The witch is invoked in visual and symbolic ways, with feminists wearing archetypal witch hats and other costumes, carrying broomsticks, and using props that resemble fire. Demonstration styles range from serious to playful, and from a considered, strategic method of protest to a passing reference. For some the sartorial representation is central, whereas for others the costume is unnecessary because their practice of witchcraft is embodied. 3 In turn, competing narratives of the witch play out in feminist spaces, ranging from revelatory and freeing to appropriative and commercialized.

The figure of the witch inspires a feeling of shared subjugation and a collective validation of subjugated knowledge, whether the general knowledge of witches’ healing practices or the specific knowledge of how to provide abortions. The witch also invokes a longer history of misogyny, colonialism, and racism that has manifested in different ways across time, with complicated implications for contemporary feminists. The sentiment has been particularly resonant in places where right-wing ideologies prevail, which is why Argentina’s Green Wave and Poland’s Black Protests have shown an embrace of the figure of the witch in an unprecedented number of transnational feminist strikes. 4 In Argentina and Poland green and black witch hats regularly appear among the striking masses, along with signs declaring the popular slogan “we are the granddaughters…” and others identifying with witches and witchcraft.

Because the witch invokes such a long history and because it has had different trajectories of subjugation in different geopolitical contexts across time, the use of the witch in transnational feminist movements carries with it several tensions. The witch has been variously racialized, cast as gender deviant, or construed as an uncivilized, un-Christian, colonial other. When feminists wield the witch as a tool in their struggle for reproductive justice they invoke these tensions, whether consciously or not. They may invoke the witch to bridge anti-racist, decolonial, queer, transgender, and feminist struggles, but they also risk invoking the archetype as a singular figure, glossing over differences or historical legacies that complicate their position in the present. This is why feminist accountability is crucial in bringing the nuanced history of the witch into our present moment of transnational mobilization against right-wing forces. A comparative exploration of how Argentinian and Polish feminists interpret and invoke the witch demonstrates its complex histories and equally complex contemporary resonances, as well as the potential pitfalls of creating a singular figure out of something so capacious to symbolize a movement.

Transnational Feminist Resonances: The Green Wave and The Black Protests

On October 3, 2016 more than one hundred thousand Polish feminists responding to a proposed ban on abortion went on strike. Sixteen days later in Argentina feminists mobilized an anti-femicide strike to protest the murder of Lucia Perez. 5 These national actions in response to local issues and in global solidarity spread to over twenty countries. 6 In 2017 these movements converged with a collective strike on March 8, International Women’s Day. Many contend that this global strike re-politicized the date and, as Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser write, reconnected it “to its all but forgotten historical roots in working-class and socialist feminism” and, I would add, transnational feminism. 7

What makes these simultaneous strikes transnational is not their happenstance occurrence across national boundaries but the quality of the mobilizations and analysis behind them. Transnational feminism involves meaningful exchange of analyses, tactics, and resources between distinct political, social, and cultural contexts. It is also a conceptual framework capable of analyzing the specific conditions of a given place and time and the interconnectedness of seemingly distinct geopolitical contexts and histories. Describing the onset of the 2017 international feminist strike, Verónica Gago writes in Feminist International: How to Change Everything, “Compañeras around the world would simultaneously do similar things: coordinated by slogans and institutions, by practices and networks… we were magnetized by a strange shared feeling of rage… connected by images that accumulated as a password: from the streets to the internet… sealing [ourselves] as part of a transnational, multilingual imagination.” 8 Polish and Argentinian feminists experienced these similarities and exchanges that made their movements transnational. One of the ways that Poland’s Black Protests enacted its transnational exchanges was through social media. The formation of online groups facilitated the exchange of ideas, images, and symbols with other feminists around the world. Slogans and images from the Black Protests traveled to other regions, including Argentina, while the voices in these regions along with their ideas, images, and symbols traveled back to Poland and became integrated into Polish feminists’ discourse. 9 These exchanges also manifested in their respective material cultures. For instance, the green handkerchiefs emblematic of Ni Una Menos were taken up by Strajk Kobiet protesters. In the case of the Black Protests, feminists across the globe who posted images of themselves, either alone or in groups, holding physical solidarity signs signaled a transnational unity. 10 Gago writes, “The potencia of the resonance of the strike, as a process, has to do with the capacity to connect at a distance and with the mobilization of meanings instigated by the circulation of images, slogans, actions, and gestures.” 11 Ni Una Menos and Strajk Kobiet demonstrated this power.

Another key aspect of transnational feminism is its ability to “root and territorialize itself in concrete struggles” and “produce links starting from those specific struggles.” 12 Transnational solidarities must transcend the nation-state and the tendency to compartmentalize oppressions into single-issue or universal struggles. 13 This is part of what distinguishes transnational feminism from international or global feminism, which assumes that all women are “natural and inevitable sisters in struggle against a universal form of patriarchy,” forgetting the possibility of a broader gender liberation, let alone liberation from capitalism, colonialism, and racism. 14 Transnational feminism recognizes the situatedness of each struggle and advocates for broad liberation through shared unity based on common interests as opposed to assumed common experiences. 15

Argentinian feminists demonstrated their transnational framework through their multi-issue approach to organizing and coalition building. Ni Una Menos has went beyond “self-declared feminist organizations” to include compañeras from unions, organizations of Indigenous peoples, organizations of Afro-descendants, migrant collectives, and more. 16 The term travesti, usually referring to transfeminine people and those identifying with gender fluidity, has also become a popular identification among Argentinian feminists who mobilize as a collective of “women, lesbians, trans people and travestis.” 17 Poland’s Black Protests have been described similarly as “intersectional, inclusive and internally-diverse.” 18 In turn, this transnational feminism goes beyond “stale oppositions between identity politics and class politics” offering vital alliances amidst the global rise of right-wing regimes. 19

Within the context of transnational feminism, the conjuring of the witch has fortified as well as complicated feminist activism for gender and reproductive justice. The witch signifies common struggles against capitalist, religious, and racial violence as well as the specific histories of colonization and Indigenous persecution, witchcraft and witch persecution, and gender-based violence and gender transgression, among other things. Making connections of solidarity through a figure that existed differently in each context can produce challenges. Feminists run the risk of invoking the witch as a universal symbol without its site-specific experiences and histories. This is why we must pay attention to the complex and varied histories inherited under the mantle of the witch.

Feminism and Witches: A Genealogy of Bodily Autonomy

In Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Silvia Federici documents the role of witch hunts in the advent of capitalism. 20 She recounts the global mass torture and killing of women during the 16th and 17th centuries not as spontaneous acts but as a highly organized punitive regime targeting women and gender deviant people for collective discipline. 21 The witch hunts were largely guided by the Malleus Maleficarum, a decree outlining the nature and proper punishment of witchcraft. 22 The authorization of this decree enabled the “construction of a new patriarchal order where women’s bodies, their labor, their sexual and reproductive powers were placed under the control of the state and transformed into economic resources.” 23 The conceptualization of witchcraft and its persecution were gendered and state-making phenomena. In Europe “women only achieved the status of subjects in their own right in the eyes of the law for the purpose of being accused, en masse, of Witchcraft.” 24 Notably, during this time the only other crime for which more women were persecuted was infanticide. 25

In Europe and the Americas infanticide, reproductive autonomy, non-procreative sexuality, and non-Western healing practices were tied to the persecution of witchcraft. 26 The witch became the “anti-mother,” a figure of gender deviance. 27 As healers and “traditionally the depository of women’s reproductive knowledge and control,” they represented a threat to patriarchal and state population management. 28 Hence, as providers of alternative knowledge and practice that enabled bodily autonomy, it is unsurprising that the witch hunts were a partial “attempt to criminalize birth control and place the female body, the uterus, at the service of population increase and the production and accumulation of labor-power.” 29 From the witch hunts onwards, contraception, abortion, and infanticide have been weaponized by those in power to regulate and restrict women’s bodily autonomy. 30 The witch hunts also “enabled the official doctors of the period to eliminate competition from female healers.” This paved the way for models of modern Western medicine that renders these knowledge paradigms as irrational and inconsequential. 31

Importantly, the history of the witch is not a universal one but rather multiple histories that must be situated in their respective contexts. Beginning in the 16th century in what is now contemporary Poland, over two thousand witches were executed, marking one of the highest rates of execution in continental Europe. 32 During this same period Poland was home to Europe’s largest Jewish population. 33 Not only did Catholic polemicists often equate witchcraft and Judaism, but there were many parallels between accusations against witches and Jews. 34 For instance, the accusation that the witches’ sabbat served as a setting for satanic ritualistic activities mirrors allegations made against the Jewish sabbath. Jews, like witches suspected of conspiring to corrupt Christianity, were deemed a threat to the Catholic Church. Finally, “only Jews and witches were considered capable of the atrocities of cannibalistic infanticide.” 35 Hence, as argued by Mona Chollet, “the demonization of women as witches had much in common with antisemitism” and it is likely that some witches were targeted not only for their counter-institutional healing practices and sexual and gender deviance but also for their Jewishness. 36

Argentina presents a very different history. Between the 16th and 18th centuries Argentina was colonized by the Spanish Empire and an estimated two hundred thousand Afro-descended Black people were taken captive and forcibly brought to the country through the transatlantic slave trade. 37 Here, as Federici recounts, the witch hunts were a deliberate colonial strategy to manage both Black and Indigenous populations. “Charges of devil worshiping were brought to the Americas to break the resistance of the local population, justifying colonization and the slave trade in the eyes of the world,” she writes. 38 Women most fervently defended their mode of existence and resisted the new power structures imposed by the colonizers. In the eyes of the colonizers this resistance gave grounds for their further marginalization. 39 Thus by persecuting women as witches, colonizers “targeted both the practitioners of the old religion and the instigators of anticolonial revolt.” 40 During this period of colonization, transatlantic slavery, and witch hunts came the emergence of new knowledge systems such as Western medicine and Western science that challenged the authority of women healers and provided scientific and medical justification for anti-Black racism. 41 As colonial regimes in the Americas sought to control the productivity of the enslaved and colonized labor forces, they were particularly “suspicious of women’s activities in the realm of healing and midwifery.” 42 This suppression of reproductive knowledge, pursued in the name of modernization and Western medicine, was underpinned by racist ideologies that attempted to control Black and Indigenous people and contain and ultimately eliminate Black and Indigenous cultures. Despite living in a “period where there was increased condemnation for procuring abortion, women continued to circulate knowledge and employ the techniques of inducing early labor to regulate their pregnancies.” 43 The witch hunts did not destroy these ways of knowing. 44

In the figure of the witch feminists inherit converging histories of marginalization, criminalization, and punishment; anti-Indigenous and anti-Black racism, antisemitism, and colonialism; and the persecution of Indigenous healers and reproductive healthcare practitioners working outside institutional Western medicine. This complexity poses challenges for a symbol of unity and any given set of demands, but it also carries the potential to bridge struggles through an intersectional feminist praxis. The witch could be ideally suited to feminist struggles for reproductive justice and bodily autonomy. The political and feminist use of witches offers a visual, historical, and ideological counterpoint to the anti-gender, anti-choice, and ultra-conservative agendas in Poland, Argentina, and globally.

The Return of the Witch to Neoliberal Politics

In Latin America and Europe alike histories of witch hunts and trials have influenced contemporary conceptions of the witch. Witches have been invoked as fairy tale antagonists, feminist icons, and misogynistic caricatures. In Poland witches often appear as the archetypal “baba yaga”; “Baba” is a term that can mean “woman” or “old woman” but also “cunning woman” and is often used in a derogatory manner. 45 Like the baba yaga, the “bruja” does similar work in the Latin American cultural imagination. A bruja is an Indigenous witch, but some use the term “bruja” or “bruja mala” (bad witch) in a derogatory way to describe a practitioner of evil or sexual magic. This carries racialized undertones. Some, reclaiming the term, call the feminism that has emerged in this context “witch feminism” or “bruja feminism.” 46 In Poland and among diasporic Poles and Jews the derogatory meaning of baba yaga has also been reclaimed.

The use of witch iconography in feminist activism and the act of forging connections between witches and feminist issues is not new. For instance, in the 1960s, W.I.T.C.H (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell) invoked the symbolism of the witch in their public demonstrations against neoliberalism, capitalism, and Wall Street. 47 During a Wages for Housework march in Naples in 1976 thousands of women shouted, “Tremble, tremble, the witches are returning, not to be burnt but to be paid!” 48 In the more recent past, following the U.S. election of Donald Trump in 2016 feminists staged witchcraft rituals and mass hexing to protest the white supremacist and proto-fascist ideologies represented by the new president. 49 The witch has also been embraced as a queer figure, one that speaks to a history of gender deviance and offers an empowering identity. Witchcraft has influenced queer thinking and activism on several occasions, for instance, in Arthur Evans’s 1978 Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture. A notable gay rights activist in the 60s and 70s and co-founder of the Gay Activists Alliance, Evans’s work connected the contemporary subjugation of queer lives with the persecution of witches for their sexuality in the middle ages. 50 Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture became a foundational text for the Radical Faeries, a queer countercultural and spiritual movement. 51 These disparate examples demonstrate that the political act of reclaiming the witch intentionally ties every symbol of gender deviance to “the very symptoms of witchcraft: refusal of motherhood, rejection of marriage, ignoring traditional beauty standards, bodily and sexual autonomy, homosexuality, aging, anger, even a general sense of self-determination.” 52 Across time and a range of political and cultural contexts, witch iconography retains an enduring significance.

The attacks on reproductive healthcare and autonomy in contemporary Argentina, Poland, and elsewhere provide an impetus for many feminists to embrace the figure of the witch in political ways. The connection between witches and reproductive labor has a long history. As Federici documents, reproductive labor is “an exploitation upon which all of capitalism rests.” In the transition from feudalism to capitalism, women’s reproductive labor — particularly birthing and raising the new labor force — needed to be naturalized to sustain the new economy. States managed this through the cultural and political imposition of domesticity and the elimination of non-sanctioned practitioners of medicine. 53

Today’s attack on reproductive healthcare occurs in a different economic context, one of neoliberal medicalization and late-stage racial capitalism where state control of reproductive autonomy is still on the agenda. Some of the manifestations of these politics include massive health-related debt, lowered quality of reproductive care, Black maternal mortality rates, and other obstetric violence. 54

Additionally, in both Poland and Argentina links between racist, anti-gender, and antisemitic ideologies in contemporary right-wing discourse animate oppositional links in the figure of the witch. Poland’s Law and Justice party, which ruled from 2015 to 2023, was known for antisemitic and anti-gender rhetoric and discourses that linked the two. Polish feminist activist and writer Agnieszka Graff argues that “anti-genderism inherits its conspiratorial and polarizing structure and repeats many of the stereotypes of gendered antisemitism, which construed Jews as demonic figures prone to decadence, perversion, sexual ambivalence, moral chaos, intellectualism, and a desire for domination.” 55 According to Graff, the country has become a place where anti-genderism is “central to Church teaching and where openly antisemitic views have been successfully mainstreamed by right-wing populists.” 56 The Law and Justice party actively sought to suppress free speech on the topic of the Nazi Holocaust through legislation. In 2018 the Polish parliament passed an Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance, what became known as the Holocaust bill, to criminalize speech and writing addressing crimes by Poles against Jews and to target Polish scholars and historians working on Holocaust education. 57

Contemporary Argentine politics are loaded with the country’s longstanding national mythology as a land of white Europeans. This story disavows Black and Indigenous people and history and perpetuates racist, colonial, and sexist genealogies of violence in contemporary culture and politics. 58 On the reclamation of the bruja in Latin America, Irene Lara writes that the “current fascination with witches in mainstream media conveys the message that white women witches are okay—particularly if they embody what dominant culture deems attractive (that is, fair skin, youth, and thinness)—but that brujas are of another species altogether.” 59 This mythology is pervasive and perpetuated by the general culture as well as by politicians in widely broadcast speeches. For example, former neoliberal and right-leaning president Mauricio Macri during his 2018 address at the World Economic Forum asserted that “in South American, we are all descendants from Europe.” Javier Milei has made similar statements. 60 Even the reclamation of the bruja in some contexts whitewashes the figure with a Eurocentric history.

Writing in the early aughts, Federici posits that “the revival of magical beliefs is possible today because it no longer represents a social threat.” 61 Pairing this thought with the “bankruptcy of liberal feminism,” the witch risks becoming a co-opted figure emptied of its real, complicated power in the current neoliberal moment. 62 Literary author Carmen Maria Machado echoes this worry:

Nowadays, witches have become a neoliberal girlboss-style icon. That is to say, capitalism has gotten a hold of her; and like so many things capitalism touches, she is in danger of dissociating from her radical roots. What could once have gotten a woman killed is now available for purchase at Urban Outfitters. 63

Indeed, in Poland and Argentina the proclamation “We are the granddaughters of the witches you could not burn” appears on products sold at Amazon and Etsy and are marketed with other commodities displaying feminist slogans and imagery. 64 Even female spirituality and the practice of witchcraft have entered the market “for personal growth and inner (re)connection in pursuit of wellbeing” (author’s translation). 65 With its complex histories and its contemporary neutralization as a market commodity, the witch does not offer feminists a simple symbol for unity in resistance. This then raises the question: can the witch in its total complexity still function as a symbol of radical feminist opposition? The apparent ubiquitousness of the witch proves its significance to even the most radical feminist movements. What these movements and individual feminists demonstrate is that in order to avoid commercialized cooptation and generalization that centers the power and political demands of white cis women, the use of the witch must acknowledge its radical roots and varying histories. Only then can movements seize the witch’s potential as a bridge across time, geography, and difference, resist capitalist cooptation, and challenge power.

Conjuring Witches in Contemporary Argentina and Poland: A Cultural Analysis

ARDA is an Argentinian feminist artivist collective that engages with the figure of the witch. Founded by lesbian activist clodet garcía, the collective is transfeminist and actively advocates the intersectional stance of Ni Una Menos. The collective proclaims a “desire to change everything,” expressing rage over former-president Macri’s neoliberal and right-leaning leadership, the patriarchy, and the Roman Catholic church. The collective has staged several public performances. In some members assemble in circular formations and engage in rituals, including acts of burning and collective chants evocative of Witches’ Sabbaths. In the collective’s words, “We get together in a circle and burn our fears, it is ritual, we are the granddaughters of the witches who could not burn… together, we burn and dance…centuries of cruelty and violence” (author’s translation). 66

ARDA’s use of witch symbolism and the phrase “we are the witches…” works on multiple levels. First, witches and witch symbolism, like fire, help transform pain and fear into action and liberation. Second, the slogan is both a call to action and a source of resilience in the face of threat. As garcía has said, “It is a phrase that speaks of the fact that we the rebellious and unsubmissive have resisted and survived” (author’s translation). 67 By invoking history, the phrase links contemporary resistance and the conditions of struggle, including witch hunt-like attacks on gender deviance. Its oppositional stance is also empowering. As another ARDA member Ana Clara Rojas said, “Hearing us shout that phrase is provocative for many! And I like that it is! Here we are despite you! We are here to shout for those who are not here! Here we are being together!” (author’s translation). 68 The witch provides ARDA members a means to transform their stigmatized and marginalized experiences into what they call “una armadura metafórica” (a metaphorical armor).

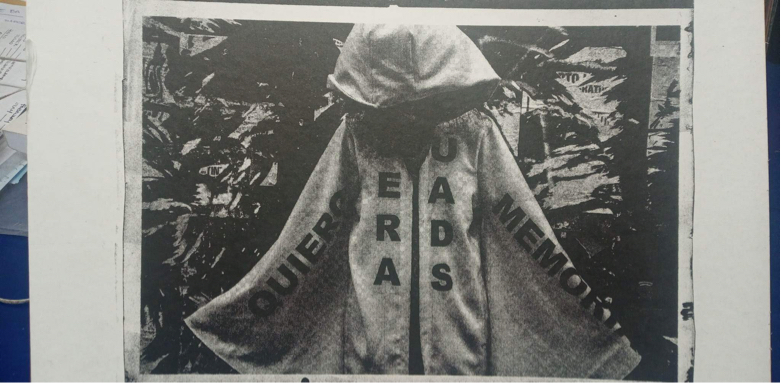

Claudia Ricca is a visual artist whose short film “Arderás” (“You Will Burn”) was developed against the backdrop of the feminist strike. The film depicts her in a draping white cloak repeating a phrase also printed on the cloak’s sleeves: “Quiero. Quiero que ardas. Que arda memoria. Quiero. Que ardas. Que arda memoria. Quiero memoria. Arde. Arde. Que ardas. Que ardas. Quiero que arda memoria. Memoria. Memoria. Arderás.” 69 (I want. I want you to burn. Memory burn. I want. I want you to burn. Memory burn. I want memory. Burn. Burn. Let it burn. Let it burn. I want memory to burn. Memory. Memory. You will burn [author’s translation].) Throughout the film’s fifty-three seconds, Ricca appears in locations associated with state violence, such as the Argentine congressional building where torn-down pro-choice posters are visible in the background (see figure 2). Ricca may be invoking a range of past injustices at play in present-day Argentina, but the two issues at the heart of her work are the rising number of femicides unlikely to decrease under President Milei and the renewed criminalization of abortion. 70 Many have analogized these attacks to earlier eras, calling them contemporary witch hunts.

Another public feminist figure María Flor Freijo echoes the outpouring of rage against these right-wing political regimes through the figure of the witch. On Instagram she posted a raging and widely shared appeal which concludes, “Busquen quemar a todas las brujas, volvemos siempre. La historia revive el fuego de nuestros nombres, entre cenizas solo quedan los enanos del poder.” 71 (You seek to burn all the witches, we always come back. History revives the fire of our names, among ashes only the stumps of power remain [author’s translation].) Reading like a witch’s spell, Freijo’s post subverts what was once used to destroy witches, reclaiming that fire as the power witches have now. However, her universal call, although broadly inclusive, does not explicitly establish solidarities between interconnected struggles and the communities most brutally targeted by contemporary right-wing politics. Discourses like Freijo’s have the tendency to marginalize Black and Indigenous struggles in favor of unity and thus offer less potential to transform conditions of the present and more potential to harm.

Black, Indigenous, and women of color feminists have challenged universal expressions of collective rage such as these. In 2020 Dominican activist Jennifer Rubio posted a statement on social media that began, “Querida feminista blanca: no eres nieta de ninguna bruja, tu abuela era católica y hace 500 años habrías esclavizado a la mía.” 72 (Dear white feminist, you are not the granddaughter of any witch, your grandmother was Catholic and 500 years ago you would have enslaved mine [author’s translation].) The statement was circulated on social media through subsections of the Green Wave across Latin America where feminists urged each other to grapple with the reality of different ancestral and healing histories and different relationships to power and subjugation.

When Argentinian activist Georgina Orellano reposted the statement she situated it in Argentinian discourse, challenging the country’s whitewashing tendencies. 73 Some Chicana and Latina academics and activists had already heeded the call, reclaiming the bruja and bruja positionality to oppose Eurocentric and colonial religious and patriarchal ideologies. By reckoning with the brujas’ colonial legacy, these activists and scholars can disentangle misogynistic and racialized tropes and situate the bruja in interlocking struggles. 74

ARDA has made such attempts to challenge the erasure of racial histories in Argentina by explicitly forging solidarities in their performances. For instance, during an intervention staged in a church ARDA recited a list of sins committed by the Catholic Church, condemning colonial crimes against Indigenous communities and the torture of witches, including burning women alive. 75 By connecting the subjugation of the witch and Indigenous people these activists demonstrated a consciousness of intersecting histories and oppressions. The intervention not only challenged the white mythologization of Argentinian nationhood, but it also asserted the witch as a figure to be reclaimed on the very grounds of its colonial oppression. ARDA also makes efforts to affirm an anti-racist and trans-inclusive agenda. Supporting the international strike on March 8, 2019, ARDA made a collective cry “for the Black women, the migrants, the non-binaries, for the girls, for the disappeared, for the dead, for the discriminated!” (author’s translation). 76 ARDA’s nuanced engagement with the witch mobilizes its transformative potential. Although imperfect, in their hands the witch appears capacious and complex enough to accommodate solidarity between interlocking struggles and to assert more inclusively and thus more accurately who makes up the “striking body” in Argentina. As Gago argues, “The strike is able to be transversal, is able to give collective voice to so many kinds of people, precisely because it is rooted in the shared materiality of our precarity.” 77 As ARDA demonstrates, the witch can be a bridge across the particulars of differing precarities.

While Argentinian feminists declare themselves to be the witches the state could not burn, Polish feminists demand, “When will you burn witches again?” 78 This slogan implies a state of national regression in reference to recurring attacks and collective discipline of those who support, provide, or undergo abortions through criminalization, arrest, prosecution. As in Argentina, Polish feminists have called these attacks contemporary witch hunts and in their strikes have cursed their government. One such curse is the frequently used slogan “wypierdalać,” meaning “fuck off/get the fuck out,” while another commonly heard slogan declares, “We are witches, fear us!””(figure 2) (author’s translation). 79 Female vulgarity is widely perceived as taboo in Polish culture, which draws another parallel between contemporary feminists and witches through this transgressive act.

One group, the Chór Czarownic (the Witches Choir), has extended the reclamation of the witch into their musical practice, incorporating references to the history of witchcraft in their lyrics. 80 The tale of the first Polish woman burned at the stake in 16th century Poznań served as their catalyst; now they aim to revive public awareness of witch trials in Poland. 81 Their song “Twoja władza” (“Your Power”) became an anthem for the Black Protests, operating as a soundtrack during marches. Another song, “Już płonę” (“I Am Already Burning”), combined with the choir’s impassioned voices and scream-like singing, conjures the historic images of witch burnings while the lyrics bring the image into the present (author’s translation). 82 “Już płonę a jeszcze” (“I am already burning, yet still”), they sing, calling attention to the continued attacks while declaring survival (author’s translation). The group’s “ritualistic quality” represents an “obvious sacrilege in a Catholic culture that persistently excludes women from the sacred” and subverts a central national and religious institution. 83 Linking the present condition of women in Poland to that of 16th century trials, the group makes a provocative genealogical connection, mobilizing widespread premonitions of a coming regression to a dark chapter of collective history. Despite similarities to the ritualistic and anticlerical sentiments of ARDA, the Witches’ Choir does not explicitly forge solidarities across groups and intersecting issues, thus confining the potential of the figure to the bounds of group identity.

Polish feminists face a culturally specific set of repressive conditions where attacks on reproductive health, antisemitism, anti-immigrant racism are rising with right-wing ideologies. When Polish women protested the insufficient care they receive when seeking abortions, anti-choice activists responded that “decent women who do not seek abortions have nothing to fear.” 84 This implies that women seeking abortions are morally deviant. Although they are not called witches, it can be analytically useful to say that the way they are treated is like witches. Anti-choice activists denounce abortions as “complicated, bloody, and dangerous,” not entirely unlike the characterization of traditional healers’ practices in this and other eras. Women seeking abortions feel tortured —as the slogan “Stop torturing women!” indicates—and face physical injury and potentially death, not unlike those stigmatized as witches. Feminists organizing to provide abortions, such as the Abortion Dream Team, a grassroots collective that shares methods to safely terminate a pregnancy and a central actor in the Black Protests, have since 2020 faced repeated backlash and prosecution, drumming up an atmosphere of witch hunts for those on the side of reproductive justice. 85 Justyna Wydrzyńska, co-founder of Abortion Dream Team, for example, was arrested for supplying a woman in an abusive relationship with abortion pills in 2023 and convicted. Many fear this sets a dangerous precedent, putting doctors, patients, and activists at risk and driving abortion provision underground. 86

In this context what does the connection to the witch hunts mobilize beyond an intense accumulated frustration? 87 One possible explanation is that in a hostile dominant culture marginalized groups find protection and resources in collective pasts to mobilize politically and provide one another with things as practical as remedies for illnesses and the tools for completing an abortion. And yet, the association is not merely analytical. Right-wing ideologies explicitly denounce feminist activists as witches and, according to Chollet, “misogynists too, as ever, appear to be obsessed with the figure of the witch.” 88 Polish media and right-wing political leaders have called Strajk Kobiet activists like Marta Lempart and outspoken feminist figures like film director Agznieska Holland, who is also Jewish, “anti-Polish witches.” 89 They frequently accuse feminist activists of being possessed by a collective madness and in need of exorcism. What else could explain their challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church and other far right forces? 90

Conclusion

The Green Wave and Black Protests find common ground in their political use of the witch. Witches make for a useful representation for contemporary feminists and reproductive justice activists because, in different ways in their respective times, witches practiced medicine that was criminalized and punished. Their healing practices included midwifery, abortion, and other care that enabled reproductive autonomy. Contemporary feminist and queer uses of the figure across geographies, political circumstances, and histories offer an opportunity to forge transnational alliances and solidarities across differences, but it also poses challenges. Reclaiming the witch as a universal symbol erases antisemitic, colonial, and racist histories of the figure. Contemporary invocations of witches risk reproducing not just erasures but material harms within feminist movements and the broader culture. The stakes are high. But when the witch is embraced in its entirety, the figure may forge a critical intersectional alliance through which feminists can struggle toward liberation.

ENDNOTES

- Daniel Politi, et. al, “Argentina Legalizes Abortion, a Milestone in a Conservative Region,” The New York Times, December 30, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/30/world/americas/argentina-legalizes-abortion.html.[↑]

- Daniel Tilles, “Will Poland Have a Referendum on Its Abortion Law, and What Might the Outcome Be?,” Notes From Poland, April 3, 2023, https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/04/03/will-poland-have-a-referendum-on-its-abortion-law-and-what-might-the-outcome-be/.[↑]

- Karina Felitti, “Brujas feministas: construcciones de un símbolo cultural en la Argentina de la marea verde,” in Religiones y espacios públicos en América Latina, ed. Renée de la Torre and Pablo Seman (CLASCO, 2021), 545.[↑]

- Cinzia Arruzza, et al., “Notes for a Feminist Manifesto,” New Left Review, no. 114 (December 1, 2018): 115.[↑]

- Verónica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything, trans. Liz Mason-Deese (Verso, 2020), 195.[↑]

- Arruzza, et al., “Notes for a Feminist Manifesto,” 115.[↑]

- Arruzza, et al., 115.[↑]

- Gago, Feminist International, 35.[↑]

- Agnieszka Graff, “Angry Women: Poland’s Black Protests as ‘Populist Feminism,'” in Right-Wing Populism and Gender: European Perspectives and Beyond, ed. Gabriele Dietze and Julia Roth (Bielefeld, 2020), 239.[↑]

- Graff, “Angry Women,” 238.[↑]

- Gago, Feminist International, 195.[↑]

- Gago, 182.[↑]

- Selin Çağatay, et al., Feminist and LGBTI+ Activism across Russia, Scandinavia and Turkey: Transnationalizing Spaces of Resistance (Springer Nature, 2022), 4.[↑]

- Corinne L. Mason, “Transnational Feminism,” in Feminist Issues: Race Class and Sexuality (Pearson, 2017), 85.[↑]

- Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (Duke University Press, 2003), 139–68.[↑]

- Gago, Feminist International, 39.[↑]

- Gago, 8; For a discussion of the term “travesti,” see Juliana Martínez, “Travesti, una breve definición,” in Sentido, January 29, 2020, https://sentiido.com/travesti-una-breve-definicion/.[↑]

- Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Korolczuk, Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment (Taylor and Francis, 2022), 151.[↑]

- Arruzza, et al., “Notes for a Feminist Manifesto,” 134.[↑]

- Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia, 2004).[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 186.[↑]

- Mona Chollet, In Defense of Witches: Why Women Are Still on Trial, trans. Sophie R. Lewis (Pan Macmillan, 2022), 8.[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 186.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 9.[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 179.[↑]

- Barbara, Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (Compendium, 1974), 24.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 31.[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 183.[↑]

- Federici, 181.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 90.[↑]

- Chollet, 33.[↑]

- Michael Ostling, “Witchcraft in Poland: Milk and Malefice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, ed. Brian P. Levack (Oxford University Press, 2013), 324.[↑]

- Ostling, 331.[↑]

- Ostling, 331.[↑]

- Yvonne Owens, “The Saturnine History of Jews and Witches,” Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural 3, no. 1 (2014): 56, https://doi.org/10.5325/preternature.3.1.0056.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 7.[↑]

- See Afro-Latin American Studies: An Introduction, ed. Alejandro de la Fuente and George Reid Andrews (Cambridge University Press, 2018).[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 198.[↑]

- Federici, 230.[↑]

- Federici, 231.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 33.[↑]

- Norell Martínez, “Brujas and the Long Struggle for Reproductive Justice,” Puntorojo, May 13, 2022, https://www.puntorojomag.org/2022/05/13/brujas-and-the-long-struggle-for-reproductive-justice-in-the-americas/.[↑]

- Norell Martínez, “Brujas in the Time of Trump: Hexing the Ruling Class,” in Latinas and the Politics of Urban Spaces, ed. Sharon Navarro and Lilliana Saldaña (Routledge, 2021).[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 220.[↑]

- Ostling, “Witchcraft in Poland: Milk and Malefice,” 320.[↑]

- Martínez, “Brujas in the Time of Trump,” 33.[↑]

- Breanne Fahs, Burn It down!:Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution (Verso, 2020).[↑]

- Anna K. Danziger Halperin, “Witches are having a moment in 2022,” The Washington Post, October 31, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2022/10/31/witches-patriarchy-halloween/.[↑]

- Martinez, “Brujas in the Time of Trump.”[↑]

- Douglas Martin, “Arthur Evans, at 68; was fervent activist for gay rights,” The Boston Globe, September 17, 2011, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2011/09/17/arthur-evans-was-fervent-activist-for-gay-rights/guwDllyO8ly3f4ujn44SOK/story.html.[↑]

- Patrick Thévenin, “Radical Faeries: in search of the Gay Spirit,” Antidote, November 24, 2021, https://magazineantidote.com/societe/radical-faeries-2/.[↑]

- Machado cited in Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 7.[↑]

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch.[↑]

- See Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (Vintage Books, 2017) and Dána-Ain Davis, Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth (New York University Press, 2019).[↑]

- Agnieszka Graff, “Jewish Perversion as Strategy of Domination: The Anti-Semitic Subtext of Anti-Gender Discourse,” Journal of Modern European History 20, no. 3 (2022): 427, https://doi.org/10.1177/16118944221120875.[↑]

- Graff, “Jewish Perversion as Strategy of Domination,” 435.[↑]

- Editorial Board, “Poland’s Holocaust Blame Bill,” The New York Times, January 30, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/29/opinion/poland-holocaust-bill-parliament.html.[↑]

- Irene Lara, “BRUJA POSITIONALITIES: Toward a Chicana/Latina Spiritual Activism” Chicana/Latina Studies 4, no. 2 (2005): 10–45, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23014464.[↑]

- Lara, “BRUJA POSITIONALITIES,”18.[↑]

- Felitti, “Brujas feministas: construcciones de un símbolo cultural en la Argentina de la marea verde,” 545; Prisca Gayles, “De Dónde Sos?: (Black) Argentina and the Mechanisms of Maintaining Racial Myths,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44, no. 11 (2021): 2094, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1823448.[↑]

- Jordan Kisner, “The Lockdown Showed How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew,” The New York Times, February 17, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/17/magazine/waged-housework.html.[↑]

- Arruzza, et al., “Notes for a Feminist Manifesto,” 114.[↑]

- Machado cited in Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 7.[↑]

- Felitti, “Brujas feministas,” 543.[↑]

- Felitti, 552.[↑]

- Patricia Fogelman, “El Artivismo Transfeminista Anticlerical En Buenos Aires: ARDA y Sus Apropiaciones Simbólicas Del Fuego,” Meridional, no. 20 (2023): 146, https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-4862.2023.70104.[↑]

- Patricia Fogelman, “El Artivismo Transfeminista Anticlerical En Buenos Aires,” 146.[↑]

- Patricia Fogelman, “El Artivismo Transfeminista Anticlerical En Buenos Aires: ARDA y Sus Apropiaciones Simbólicas Del Fuego,” Meridonal: Revista Chilena De Estudios Latinoamericanos 20 (2023): 146, https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-4862.2023.70104.[↑]

- Claudia Ricca, “Arderás”, November 2018, YouTube video, 0:53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DutRTxNBlW0.[↑]

- In conversation with Claudia Ricca, February 2024.[↑]

- Maria Florencia Freijo (@florfreijo), “Nos quieren castigar,” Instagram, February 9, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/florfreijo/.[↑]

- Jennifer Rubio (@ciguapadecolonial), “Querida feminist blanca,” Instagram, July 5, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/lacasamandarina/p/CCQ5CWCjbLp/.[↑]

- Felitti, “Brujas feministas,” 67.[↑]

- Lara, “BRUJA POSITIONALITIES,” 24.[↑]

- Fogelman, “El Artivismo Transfeminista Anticlerical En Buenos Aires,” 152.[↑]

- Fogelman, 134.[↑]

- Gago, Feminist International, 22.[↑]

- Jarek Szubrycht, “Dziunia, jesteś pijana władzą’. Galeria transparentów z protestów kobiet,” Wyborcza, November 11, 2020, https://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/56,114883,26457993,strajk-kobiet.html.[↑]

- Conversation with Agnieszka Graff, September 22, 2023.[↑]

- Chór Czarownic (The Witches Choir), “Chór Czarownic (The Witches Choir),” Facebook, September 29, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/Chorczarownic.[↑]

- Agnieszka Graff, et al., Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment (Routledge, 2022), 245.[↑]

- Chór Czarownic (The Witches Choir), “Chór Czarownic (The Witches’ Choir) – Już Płonę a Jeszcze,” October 10, 2017, YouTube video, 2:36, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yaG7cvypTg.[↑]

- Graff, et al., Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment, 247.[↑]

- Elżbieta Korolczuk, “Counteracting Challenges to Gender Equality in the Era of Anti-Gender Campaigns: Competing Gender Knowledges and Affective Solidarity,” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 27, no. 4 (2020): 709.[↑]

- International Planned Parenthood Federation, “Poland: IPPF EN Is Appalled by the Guilty Verdict in the Case of Justyna Wydrzyńska,” IPPF Europe & Central Asia, March 14, 2023, https://europe.ippf.org/media-center/poland-ippf-en-appalled-guilty-verdict-case-justyna-wydrzynska.[↑]

- International Planned Parenthood Federation, “Poland.”[↑]

- Dorota Szelewa, “Killing ‘Unborn Children’? The Catholic Church and Abortion Law in Poland Since 1989,” Social & Legal Studies 25, no. 6 (2016): 741, https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663916668247.[↑]

- Chollet, In Defense of Witches, 21.[↑]

- Conversation with Agnieszka Graff, September 22, 2023.[↑]

- Conversation with Agnieszka Graff, September 22, 2023.[↑]