On the contrary, Lê asserts the links to capital flow in Fuel Storage McMurdo, seeming to have anticipated the headlines about the price of oil. The increased volatility of oil prices has negatively affected planning and funding of the very NSF program that sent Lê, in 2008, to photograph these barrels of oil, which, in the present climate, represent a completely fossil fuel-reliant economy. 1 Oil barrels, full and stored or empty and abandoned, have, since the 1930s when a concerted U.S. effort to colonize Antarctica began, been a stock image of Antarctic stations. 2 Where a clearing of tree stumps once marked the passing of wilderness, the fuel storage tanks tell similar tales of the technology and resource needs for human being. The massive effort to create permanent structures in a wilderness is nowhere more dramatic than at the South Pole, where nothing survives but ice, and everything, from toothpicks to neutron detectors, must be flown in from the north at great effort and cost.

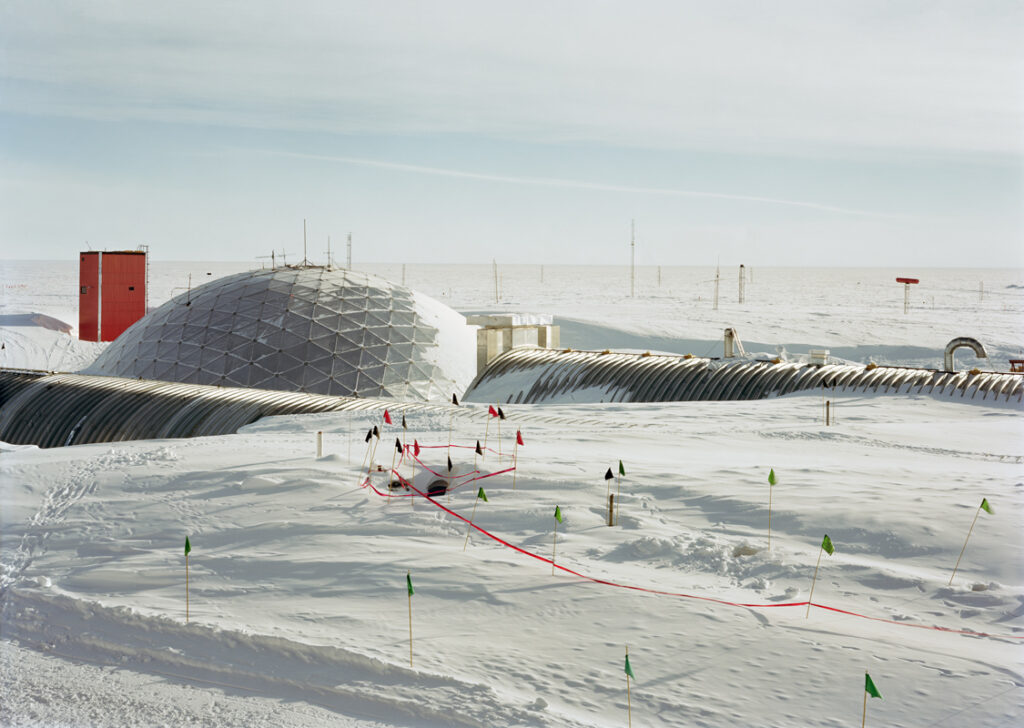

Abandoned Dome, South Pole, Antarctica, 2008

Archival pigment print

40 x 56 1/2 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy Gallery

The built environment at the South Pole, though relatively circumscribed and brief in duration, is nevertheless deeply marked by U.S. cultural projections. How many people know that a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome, or a “Bucky Ball,” is slowly being buried in the ice of the south pole, after having been planned in the late 1960s and completed in 1973 and shielding inhabitants and supplies until 2007? Lê’s image of the sunken dome that once carried Fuller’s utopian vision of “spaceship earth,” is reminiscent of Tacita Dean’s “Fernsehturm” series on modernist architecture. Sue Hubbard describes this series as “encapsulat[ing] a lost historic vision and an optimistic belief in a now defunct social system.” 3 Marks of everyday inhabitation such as flags and footprints and bright tape take on an almost macabre feel in the merciless frame: this is a ruin of a futuristic ideal, now obsolete and trapped in ice. The “deadpan” framing places the dome and viewer on the same plane, emphasizing the harsh juxtaposition of human and built environment. Lê’s photography of the built environment at the South Pole emphasizes the obsolete, the Fordist prehistory of heavy machinery and the footprint of what I will call the “U.S. Heroic Age” of Naval operations beginning in 1929 and ending with the development of the International Polar Year and the ATS in 1959. While the U.S. brokered the ATS and its international safekeeping of the territory from claims, the period of the U.S. Heroic Age nevertheless resulted in the U.S. effectively and solely colonizing the Pole by building the first permanent station in the 1950s, then the Bucky dome in the 1960s, and now the third generation of super-sleek corporate-style station, completed in 2008 and almost ostentatiously omitted by Lê.

Instead of the new station, Lê investigates the failed and inaccessible, incomplete, or buried traces of the built environment. She works against the coffee table book aesthetic; her images are enormous, not meant for containment between covers, no matter how glossy. Her high art and highly technical images negotiate between the landscape aesthetic that broke down at the Pole and the more vernacular aesthetic that visitors to, and inhabitants of, the South Pole have been attempting to reestablish. The photography of Emil Schulthess, with its use of fish-eye lenses to reflect in the mirror ball of the ceremonial south pole and its emphasis on sun dogs and other unusual weather phenomenon, is a form of updated “ponting” (after Ponting’s carefully—and to Scott’s men intrusively—staged perspectives). 4 The extremophile exceptionalism has through repetition and circulation (particularly on the internet) become an ironic if normalizing repertoire of representations of the polar plateau. 5 Lê focuses instead on the industrial infrastructure, the chaotic, menacing, and wasted space of an unredeemable blankness very different from both the blank of imperialism’s hope and the desert of Porter’s conservation aesthetic.

Storage Berms, South Pole, Antarctica, 2008

Archival pigment print

40 x 56 1/2 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy Gallery

More significant to Lê than the new station is the lost and discarded, the incoherent epiphenomenal and un-beautiful, as in Storage Berms at South Pole. Lê labels the photo using the argot of the U.S. base as it has derived from its Naval origins. The term “storage berm” refers to an earthwork or a mound formed as a result of human labor, as in the berm walls of a fortress or of mounded earth in a garden. But the South Pole is neither fortress nor garden; and the term berm can help to understand how culture in the form of language and built environment is being reshaped in Antarctica. “The berms” in ‘Polie’ patois refers to the entire storage area on the near perimeter of the central encampment consisting of the Dome, new pole station, and out buildings. An extensive sprawl of plywood platform covered with all sorts of off-loaded cargo forms an almost city-like network of streets. The berm area is like a warehouse without sides or a roof. The bermed platforms require an intensive regime of shoveling to retain their integrity. Far from the “city center” of science or logistics, the berms are the domain of mostly the lesser skilled workers, who are assigned their maintenance. It is on this shunted yet essential sprawl that Lê chooses to center her image, turning away from the central pole. If there can be a “backside” to a circumlocated pole, the berms are it. 6

The image lacks contextualizing features beyond a rudimentary and conventional sectioning into sky, horizon line, and foreground of ice. Lê destabilizes this overbearing classical perspective by mixing elements of motion and stasis. Through the overlay of compositional features, Lê also questions the very usefulness of perspective, of relative motion, tracking, and lighting. Despite the bright sunshine and the classical composition, the viewer hardly knows where to focus within the enormous frame. The perspectivally broad, flat and multi-focused approach refutes the unipolar cliché and seems to be saying that there is more here in this basic land-sky polar plateau than is generally considered; the pole becomes in this way more like other sites on earth—and in history—than in the extremophile tradition.

- See the Introduction to this special issue for the way rising oil prices have increased pressure to exploit the polar regions as possible solutions.[↑]

- Photographs of U.S. explorer Richard E. Byrd’s “Little America” bases from 1928-1938 document a built environment prominently featuring jumbled boxes and fuel cans on a field of ice. For a range of photographs depicting U.S. bases throughout the 1930s and 1940s see “All-out Assault on Antarctica,” National Geographic Magazine. CX.2 (1956): 141-180. Explicitly modeled after the Little America base, the opening shots of the Antarctic base in John Carpenter’s 1982 The Thing pans across empty fuel drums against the ice.[↑]

- See Sue Hubbard’s review of Tacita Dean at the Tate. A filmic/cultural icon of a “defunct social system” is the scene in Planet of the Apes (1968) depicting the Statue of Liberty as a beached ruin.[↑]

- Stephen Pyne, The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986, p. 205. Pyne offers a portfolio of Antarctic representation including Ponting, Porter, and Schulthess.[↑]

- The term refers to love of extremes as well as to a class of creatures that has evolved to thrive in desert conditions such as those prevailing in Antarctica.[↑]

- In a scene from her 1981 short story “Sur,” Ursula Le Guin describes her characters encountering the area around Scott’s abandoned hut. Looking much different than the famous Ponting shots, the hut area is a mass of dog turds and open spilt containers, sealskins and bloody guts. The narrator remarks: “The backside of Heroism is often sad; women and servants know that.”[↑]