Synesthetic Rhythms:

African American Music and Dance Through Parisian Eyes

"[Josephine Baker] embodies the frenzy of jazz, the hard rhythms of

modern sculpture, [and] the tormented vagaries of contemporary melodies

[...]."[1] As this 1930 article suggests, Josephine Baker, the young

American dancer who captured the hearts of the Parisian public, captured

the spirit and color of the jazz age as well. Dubbed "the Black Venus"

(la Vénus noire), "the black star," and "the empress of jazz,"

Baker experienced an extraordinary success in Paris in the 1920s. Her

performance with La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées

in Paris in 1925 launched a vogue for the black bottom and Charleston

across Europe and advanced the craze for jazz that had already overtaken

the capital.

In much of the reception of the period, the Vénus noire came

to be seen as an exemplary figure of urban modernity. The cross-play of

the arts found force in the figure of Baker, who was considered the

living embodiment of modernist art, from primitivism to German

expressionism to cubism. The premiere of La Revue Nègre gave rise

to a number of visual metaphors. For dance critic André Levinson,

Baker's plastic poses had the potency of "the finest examples of Negro

sculpture"; for a critic of Le Soir, La Revue Nègre constituted

the "quintessence of the modernism of the music hall"; one spectator

commented simply, "It's cubist."[2] In the words of contemporary critics

Karen Dalton and Henry Louis Gates Jr., "Josephine Baker was

primitivist-modernism on two legs, the cubists' art nègre in

naked, human form."[3] The frenetic pace of her dance and the liberty of

her movements seemed to provide an aesthetic response to the

kaleidoscopic fervor of the Roaring Twenties. In Baker, one saw a mirror

of modernity, a reflection of its palpitating rhythm, its perpetual

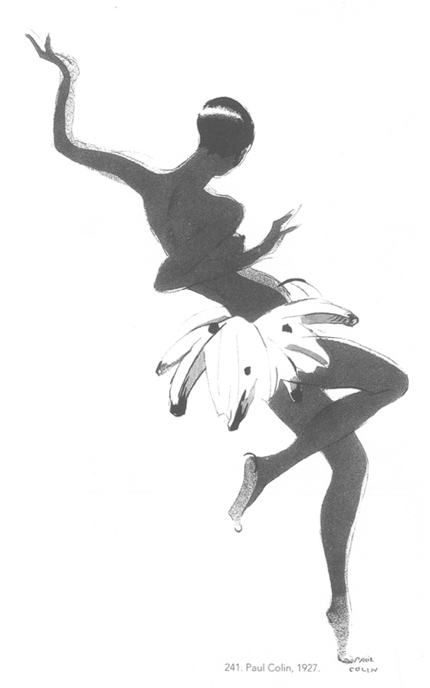

movement, its ephemeral and fleeting nature. Paul Colin's art deco

designs of Baker, which appeared in a portfolio of 45 hand-colored

lithographs entitled Le Tumulte noir (1927), capture the energy

and rhythm of Baker's movements [Figure 1]. The stark lines, bold colors,

and exaggerated angles of the drawings render Baker a vivid articulation

of the throbbing metropolis. For Count Harry Kessler, Josephine Baker

and La Revue Nègre were both "ultramodern" and "ultraprimitive."

On a performance of La Revue Nègre at the Nelson theater in

Berlin in 1926, Kessler wrote, "They are a cross between primeval

forests and skyscrapers; likewise their music, jazz, in its color and

rhythms. Ultramodern and ultraprimitive."[4]

Figure 1: Josephine Baker in her banana skirt, lithograph by Paul

Colin from Le Tumulte noir, c. 1925. Jerome Robbins Dance

Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor,

Lenox and Tilden Foundations. © 2004 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New

York/ADAGP, Paris. [Back to

text]

Primitivist modernism in motion, Baker, considered by one critic "a

saxophone in movement," embodied for many the spirit of jazz.[5] Jazz had

reached Paris as early as 1917, with the arrival of African American

regiments in France, whose bands, such as Harlem's Hellfighters and

Seventy Black Devils, performed throughout the country.[6] The most

well-known band was Lieutenant James Reese Europe's Hellfighters, drawn

from the highly decorated 369th Infantry Regiment of New York. In the

early months of 1918, the Hellfighters went on a grand tour of France,

visiting over 25 provincial French cities in a period of six weeks

(Shack 2001, p. 19). These "goodwill ambassadors" were responsible for

raising the morale of Allied troops on the front and in country

hospitals (Blake 1999, p. 62). The Hellfighters, who drew the attention

both of the armed forces and the civilian population during the war,

represented the United States at a number of ceremonies marking the

war's end. While many American G.I.'s returned home after the war, jazz

left an indelible mark on the French capital. The most famous early jazz

bands were drummer Louis Mitchell's Jazz Kings, a group of seven jazz

musicians which played at the Casino de Paris and various cabarets

across Paris, and violinist Will Marion Cook's Southern Syncopated

Orchestra, a 41-piece orchestra which gave a series of concerts at the

Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in 1921 in the wake of a European tour.[7]

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8

Next page

|