The course of women’s intercollegiate athletics was changed when, at its annual meeting in 1981, the NCAA voted in favor of offering Division I women’s championships. Ironically, this occurred at the same time that the NCAA was fighting to have intercollegiate athletics exempted from Title IX. Though the AIAW’s institutional membership had been larger than the NCAA’s, it did not have the resources, financial and otherwise, to prevent the “takeover.” A preliminary injunction and an antitrust suit were filed against the NCAA but failed. The AIAW was forced to disband in 1983, giving power and control over women’s intercollegiate sports to men.

Since 1983, NCAA leadership and the implementation of Title IX have prompted many changes, some good and others not. The number of sports has increased at almost every institution, providing thousands of college women the opportunity to compete. The number of championships has also increased, as has television revenue. The downside, though, includes the “arms race” of building multi-million-dollar stadiums and offering million-dollar coaching salaries, the exploitation of student-athletes, and a win-at-all costs mentality at odds with many of the academic goals and objectives expressed in most higher education mission statements.

In accepting the demise of the AIAW, many female coaches and administrators hoped that women and men would work together to transform intercollegiate sport. Instead, most women’s programs were modeled after the men’s, and female leadership declined. In 1972, 90 percent of women’s teams were coached by women, and 90 percent of those programs were also administered by a female head athletic director. In 2002, only 44 percent of women’s teams were coached by women (the lowest representation in history) and 17.9 percent were directed by a female head athletic director. 1 (In addition, the NCAA Executive Committee (its highest governance body) is currently composed of 17 men and 2 women. 2 Despite this loss of power and control of women’s sport, it is critical that we continue to work for structural changes in the organization and practice of sport, changes that will lead not only to gender fairness but also fiscal and academic accountability. The Knight Foundation’s Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and the Drake Group 3 are leaders in the effort to transform the institution of college sport. In a “Call to Action,” the Knight Foundation’s Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics suggests several ways to reform sport and states that “if it proves impossible to create a system of intercollegiate athletics that can live honorably within the American college and university, then responsible citizens must join with academic and public leaders to insist that the nation’s colleges and universities get out of the business of big-time sports.” 4 Transformation of college sport will not be an easy task, nor will it happen in any substantial way without the support and leadership of university presidents and regents.

Equally important to this transformation is the role of the media. They are significant in reflecting and shaping public perceptions of women and sport. Since Title IX was enacted, girls and women have entered sport in record numbers. This entry into sport is part of what Dr. Stimpson describes as one of the treatments in the liberal healing of the Atalanta Syndrome. She also acknowledges the cost, however: “the weakening of the Atalanta syndrome is extracting a price: the sexualization of the strong female athlete, the engineering of the ‘buff bunny’ or the heterosexy competitor.” 5 In an effort to gain recognition, publicity, and corporate sponsorship, female athletes are offered, and accept, promotions that emphasize their femininity and sexuality and distract from their athleticism. Though coverage of women’s sports has increased, the type of coverage has often marginalized the athletic accomplishments of women, sending the message that female athletes are “less than” their male counterparts. This demeaning representation is a modern-day Atalantan distraction, yet another symbolic golden apple, which cheering fans encourage the modern day Atalanta to pick up so that she might fall behind in the race. Numerous studies by sport scholars have documented that the popular press (sports magazines, newspapers, and television) have underreported, ignored, and trivialized women’s athletic success. 6 In addition to mainstream public media, our longitudinal research on university-controlled athletic media guides has provided similar and interestingly new results.

Click an image below to enlarge in slideshow format.

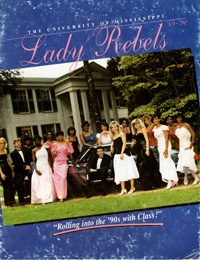

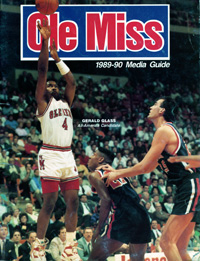

NCAA Division I media guides are representative of a powerful, highly prestigious and influential sector of organized sport. They are the primary means by which colleges and universities market their athletic teams to the press, advertisers, corporate sponsors, and prospective student athletes. They are the broader version of game programs, highlighting the teams on high-gloss, multi-colored cover photographs. A textual analysis was done on these cover photographs to investigate gender difference and hierarchy in sport. An initial study in 1990 showed that women were significantly more likely to be portrayed in traditionally feminine ways, while men were significantly more likely to be portrayed as competent athletes (on the court, in uniform and in action). Female athletes were marginalized and trivialized in these portrayals in that their femininity, rather than their athletic competence as powerful and skilled athletes, was emphasized. One university provided the perfect example: in men’s basketball, an athlete is in action executing a jump shot with two defenders guarding him and a gymnasium full of spectators in the background, while the women’s basketball team for the same school and the same year are shown in formal dresses with heavily made-up faces and styled hair, posed around a luxury car with a stately mansion in the background. The cover photograph for women’s basketball gives no indication (either by text or photograph) that the publication is about basketball. Rather, the women’s appearance suggests that they might be candidates for homecoming queen. 7

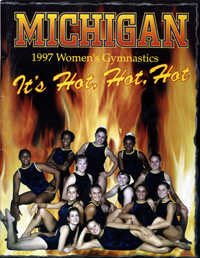

A similar pattern emerged in a 1997 follow-up study of the same NCAA Division I conferences and teams. The female athletes continued to be constructed differently than their male counterparts. For all sports, male athletes were represented as true athletes (on the court, in uniform and in action) 59 percent of the time, compared to 39 percent for female athletes. These results were surprising and disappointing, especially in light of the tremendous success of the U.S. women at the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. 8

In 2004, in collaboration with Professor Mary Jo Kane, Director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport, we replicated the previous studies and performed analyses on three categories (uniform, court, and pose) from a longitudinal perspective. In a significant departure from the previous two studies, there were no statistically significant differences between women and men. Women were overwhelmingly presented as serious, competent athletes (on the court, in uniform and in active athletic roles) 72 percent of the time compared to 79 percent for the men. Over a 15-year span, females came to be presented as “true athletes” in ways that achieved or approximated parity with male athletes. 9

From the initial study in 1990 to the most recent in 2004, there was a dramatic shift toward representing women as competent athletes. While there may be no empirical evidence to suggest a cause-effect relationship, we posited a few possible explanations for this change.

- R. V. Acosta and L.J. Carpenter, Women in Intercollegiate Sport: A Longitudinal, National Study. Twenty Seven Year Update, 1977-2004 (West Brookfield, MA: Brooklyn College and Smith College, 2004), 1.[↑]

- A full list of these members is provided at http://web1.ncaa.org/committees/. [↑]

- The Drake Group is a network of college faculty devoted to quality education for college athletes and support for faculty who are threatened for defending academic standards. See www.thedrakegroup.org.[↑]

- Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, A Call to Action: Reconnecting College Sports and Higher Education (Miami: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, 2001), 31.[↑]

- Catherine Stimpson, “The Atalanta Syndrome: Women, Sport, and Cultural Values,” Inaugural Helen Pond Lecture, The Scholar and Feminist Online, vol. 4, no. 3 (Summer 2006).[↑]

- For more information related to studies with respect to underrepresentation include but are not limited to Eastman and Billings (2001), Fink and Kensicki (2002), Kane (1996), Duncan and Messner (2005). For studies related to type of coverage, the following works are cited, but not limited to Duncan (1990), Daddario (1997), Kane and Lenskj (1998).[↑]

- To view copies of these photographs, Jo Ann Buysse, “Constructions of Gender and Hierarchy in Sport: An Analysis of NCAA Division I Intercollegiate Media Guide Cover Photographs” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1992), 89-90.[↑]

- The first two studies and their results are available in J. Buysse and M. Embser-Herbert, “Constructions of Gender in Sport: An analysis of intercollegiate media guide cover photographs,” Gender and Society 18, no. 1 (1994): 66-81.[↑]

- For complete results of this study see M. J. Kane and J. M. Buysse, “Intercollegiate Media Guides as Contested Terrain: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Sociology of Sport Journal 22 (2005): 214-238.[↑]